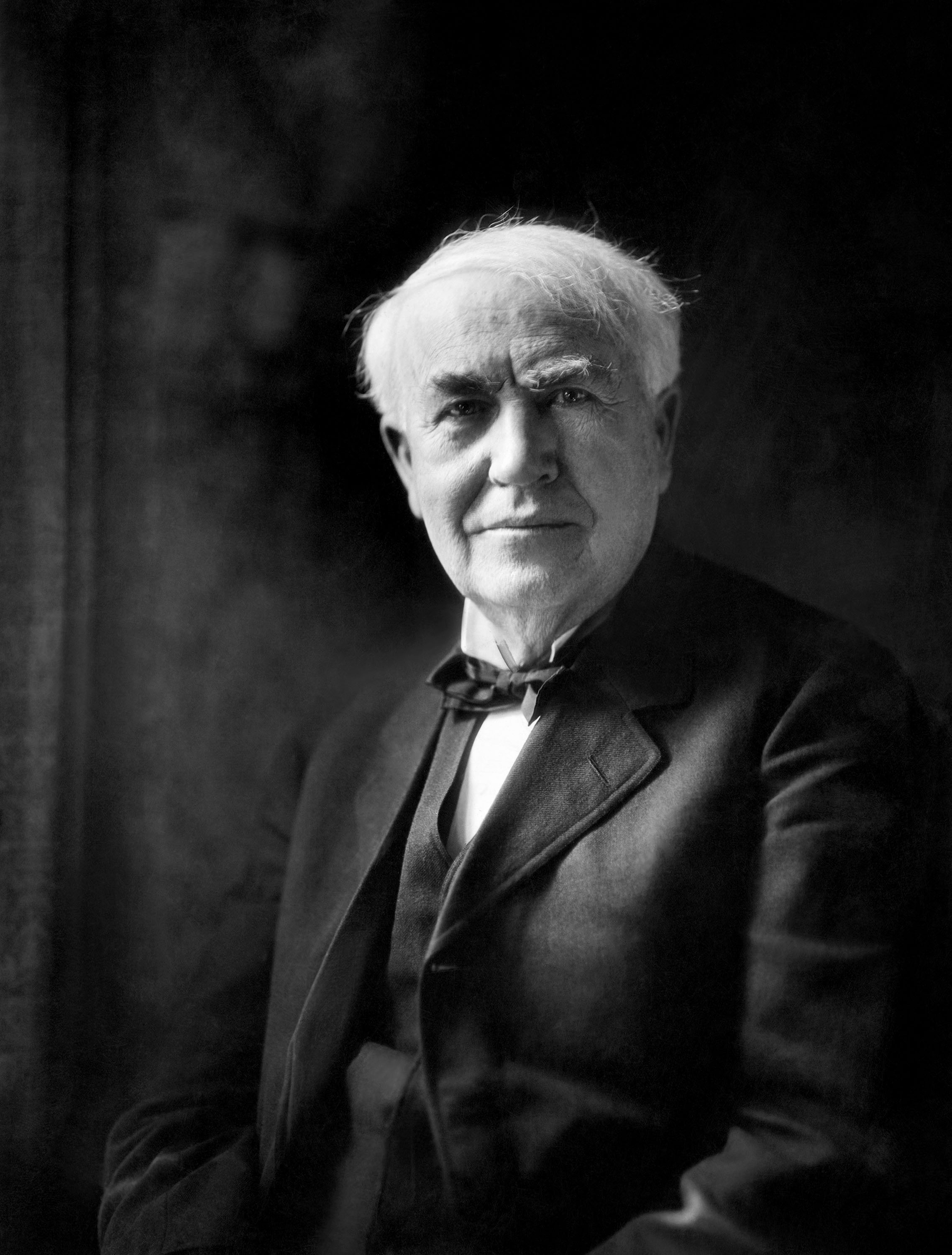

Edison, Thomas Alva (1847-1931), was one of the greatest inventors and technological innovators in history. His most famous contributions include useful electric lighting and the world’s first electric power system. He invented the first practical machine that could record and play back sound. He called this device the phonograph. Edison also made improvements to telegraphs, telephones, and motion pictures.

Loading the player...Thomas Alva Edison

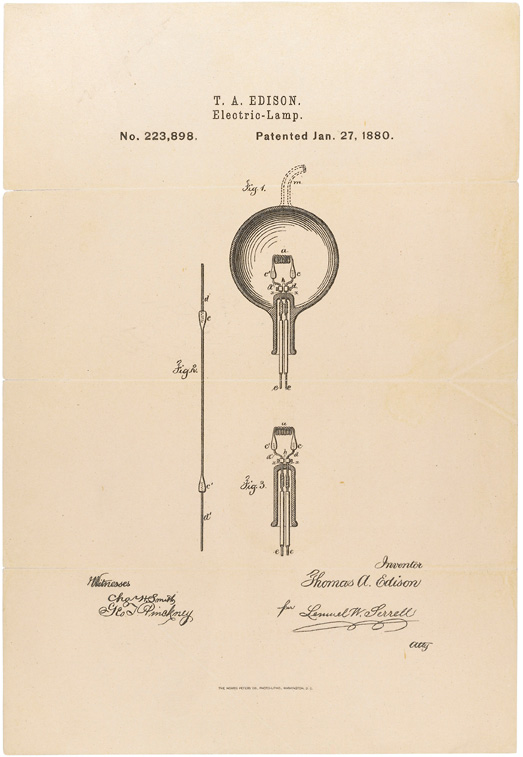

Edison looked for many different solutions when attempting to solve problems. When he created new or improved devices, he made a variety of designs. Sometimes, he borrowed features from one technology and adapted them to another. Edison obtained 1,093 United States patents, the most the U.S. Patent Office (now the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office) has ever issued to one person. Altogether, he received thousands of patents from some two dozen nations.

Edison also created one of the first modern research laboratories. Some scientists and historians regard this development as Edison’s greatest achievement. Edison’s research laboratory grew out of the way he worked. He often worked alongside his assistants. He observed how others solved mechanical, electrical, and chemical problems. Then he tried to improve upon their ideas. By the early 1900’s, many industrial corporations had seen the success of research labs and established their own.

Edison was an active businessman. He created new companies to manufacture and sell his products. Income from selling his products helped support his research laboratory and the development of more devices. As a result, Edison and other manufacturing pioneers in the late 1800’s helped make the United States an industrial world power.

Armed with self-confidence and determination, Edison overcame a number of technical and commercial failures. He became world famous by his mid-30’s and a millionaire by his mid-40’s. His name—and the electric light bulb that he designed—became worldwide symbols of bright ideas and technical creativity.

Early life

Edison was born on Feb. 11, 1847, in Milan, Ohio. He was the seventh and youngest child of Samuel and Nancy Elliott Edison. Edison’s father fled from Canada during the rebellions of 1837, in which Canadian rebels unsuccessfully revolted against British rule. Samuel Edison worked as a shingle maker and land investor. When Al—as the family called young Edison—was 7 years old, the Edisons moved to Port Huron, Michigan. There his father ran businesses in lumbering and land investing.

Early interests.

Edison received limited formal education. His mother, a former teacher, guided his learning. Edison was mischievous and inquisitive. He loved to pull pranks and practical jokes. He was also eager to read, particularly science books. His reading led him to experiment with chemicals and to construct elaborate models. He built models of a working sawmill and a railroad engine, both powered by steam.

Even as a child, Edison was interested in business. He grew vegetables on his father’s farm and sold them in town. At age 12, Edison began to sell newspapers, candy, and sandwiches on passenger trains between Port Huron and Detroit. When he was 15, he published and sold a newspaper called the Weekly Herald.

By this time, Edison had developed hearing problems. His hearing worsened as he grew older. Late in life, he could only hear people shouting directly into his ear.

The young telegrapher.

At age 15, Edison rescued the son of a telegraph operator from the path of a railroad car. As a reward, the operator gave Edison telegraph lessons. In 1863, Edison began work as a telegraph operator for the Western Union Telegraph Company. During the following four years, he worked as a telegrapher in a number of Midwestern cities. Edison learned much about the scientific aspects of telegraphic communication. He experimented with telegraph equipment. He also read newspapers, scientific journals, and books.

Inventor and businessman

In 1868, Edison moved to Boston as a telegraph operator. He soon made improvements to the process used to print telegraphs and to a device that transmitted images over telegraph lines. Edison also applied for his first patent. But the invention—an electric vote-recorder for legislatures—was never used.

In 1869, Edison moved to New York City. There he met leaders in the business community, who appreciated his work as an inventor. At the time, Edison’s inventions included improved stock tickers, telegraph devices used to report the purchase and sale of stocks. In 1870, Edison moved to Newark, New Jersey, and started a stock ticker manufacturing company.

Edison hired associates with mechanical talent to help develop a steady stream of inventions. He continually tried to improve the devices he sold. He also kept systematic notes of his activities. He used these notes to organize research and to defend his patents.

In 1874, Edison completed the design of the quadruplex, a device that made telegraphs faster and more efficient. Edison called it the quadruplex because it could send four messages at the same time over a single wire. In 1875, Edison and his staff developed an electric pen that cut stencils out of paper for copying documents.

The Wizard of Menlo Park.

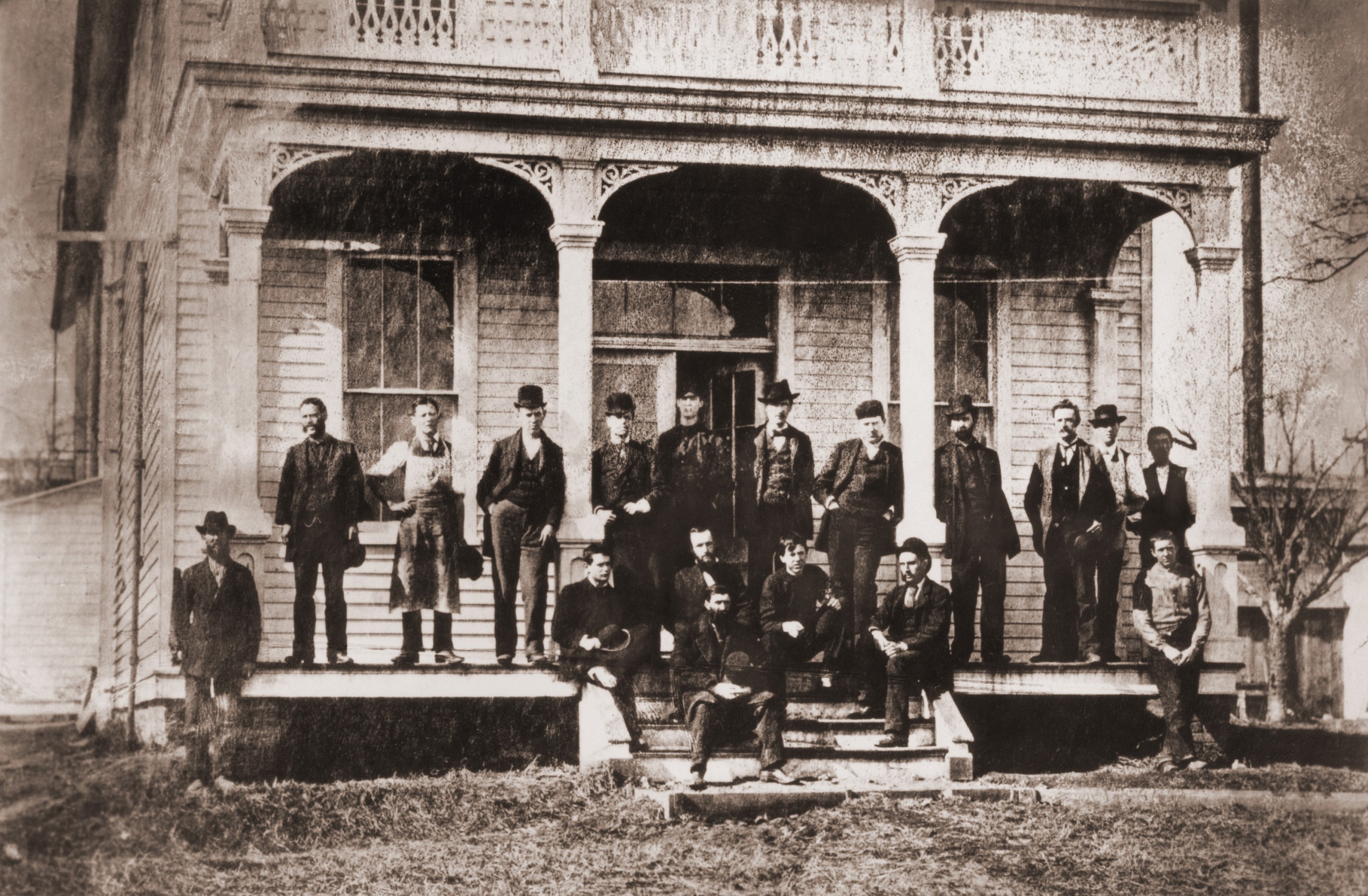

In the spring of 1876, Edison built his first research laboratory in the rural community of Menlo Park, New Jersey. The work done by Edison and his assistants at Menlo Park would make him famous throughout the world. Three of his greatest inventions originated there: (1) an improved telephone transmitter, (2) the phonograph, and (3) the electric light. Menlo Park is now part of a township known as Edison.

Telephone transmitter.

Edison was one of many inventors who improved the “speaking telegraph,” as the telephone was then called. Alexander Graham Bell, a Scottish-born inventor, patented the telephone in 1876. In 1877, Edison designed a carbon-based transmitter. It made the voice of a speaker louder and clearer over the telephone. Before his invention, people had difficulty hearing anything said over the telephone. Until the 1980’s, most phones used transmitters based on Edison’s improvement.

The phonograph.

In 1876 and 1877, Edison experimented with ways to record and replay messages. These experiments led to the invention of his phonograph. To record messages, Edison attached a needle to a diaphragm, a metal disk that vibrated in response to sound waves. The needle rested against a rotating cylinder wrapped with tinfoil. When the disk vibrated, the needle made varying impressions in the foil. To reproduce the sound, another needle was attached to a diaphragm and funnellike horn. This needle retraced the impressions or grooves in the foil. It vibrated the diaphragm and thus the air in the horn, re-creating the original sound waves.

In December 1877, Edison had a machinist build the phonograph. When it was done, he recorded the nursery rhyme “Mary Had A Little Lamb.” Then Edison showed his phonograph to the editors of Scientific American magazine. The next spring, he demonstrated it for scientists, members of Congress, and President Rutherford B. Hayes. Newspapers and magazines helped spread enthusiasm for the invention and its inventor. Edison became one of the most famous Americans alive. Stories of his childhood, pictures of his “invention factory,” and interviews with the inventor went out to the whole world. As a result, Edison became known around the world as the “Wizard of Menlo Park.”

The electric light.

In 1878, Edison began his most ambitious project. He developed a system of electric lighting to be used in homes, stores, offices, and factories. He found support for this project from J. P. Morgan, a powerful banker. Many inventors at the time were investigating electric lighting. They thought electric lighting would be cheaper, safer, and more reliable than the gas lighting that was popular in cities and suburbs.

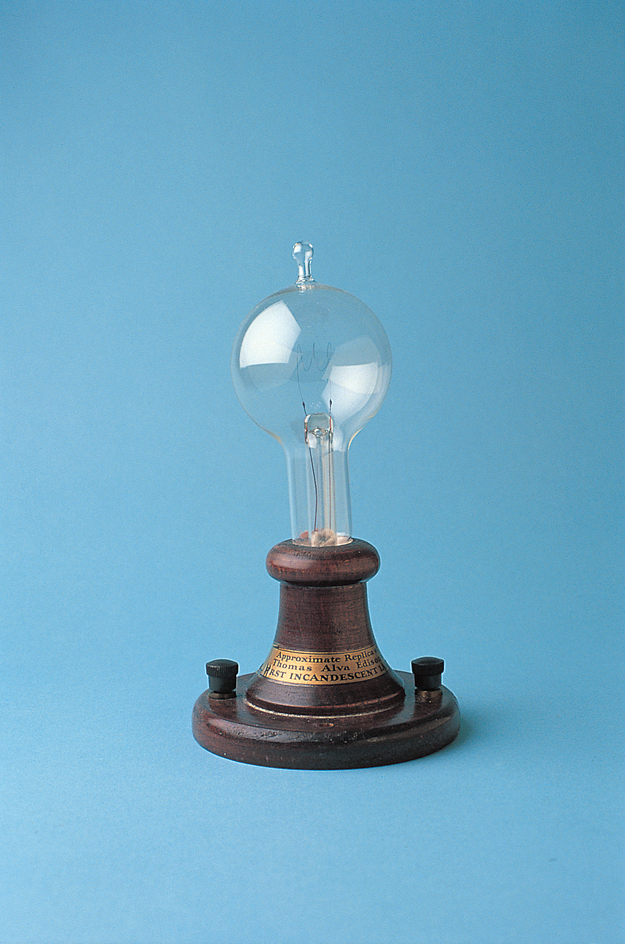

Edison threw himself and his assistants into the complex work of developing a variety of electric light and power devices. This work required a system of generators, wires and cables, switches, motors, meters, and lamps (light bulbs). The lamps were probably the most famous component of the system.

An incandescent lamp produces light by passing an electric current through a filament (fine thread or wire). The electric current heats the filament so that it glows. Edison had to figure out how to make practical, long-lasting incandescent lamps.

Edison and his associates placed the filament inside a glass vacuum bulb. They spent months searching for an affordable filament material that would produce the best light. In October 1879, they tested a carbon filament made from burned sewing thread, resulting in their first practical incandescent light bulb. In 1880, they began using bamboo filaments, which lasted longer.

Electric utilities and manufacturing.

In 1881, Edison moved back to New York City. He personally supervised the construction of his first central power station in the United States. It opened in 1882 on Pearl Street and served the business community in lower Manhattan . By 1884, this station delivered electric lighting to more than 500 customers and more than 10,000 lamps.

Edison’s agents introduced his lighting system in other countries. They established companies to install Edison’s system abroad. In 1882, small central stations opened in London and in Santiago, Chile. In 1883, an Edison central station began operating in Milan, Italy. In 1885, a major station opened in Berlin, Germany. By the 1890’s, hundreds of communities throughout the world had Edison power stations. Edison also developed and sold small generating plants. They could be used in individual houses, businesses, or ships.

Edison started companies that manufactured his inventions. The products of these companies included power stations, light bulbs, and underground conductors. In 1892, the American businesses that manufactured Edison’s electric lighting components became part of the General Electric Company.

Edison in West Orange.

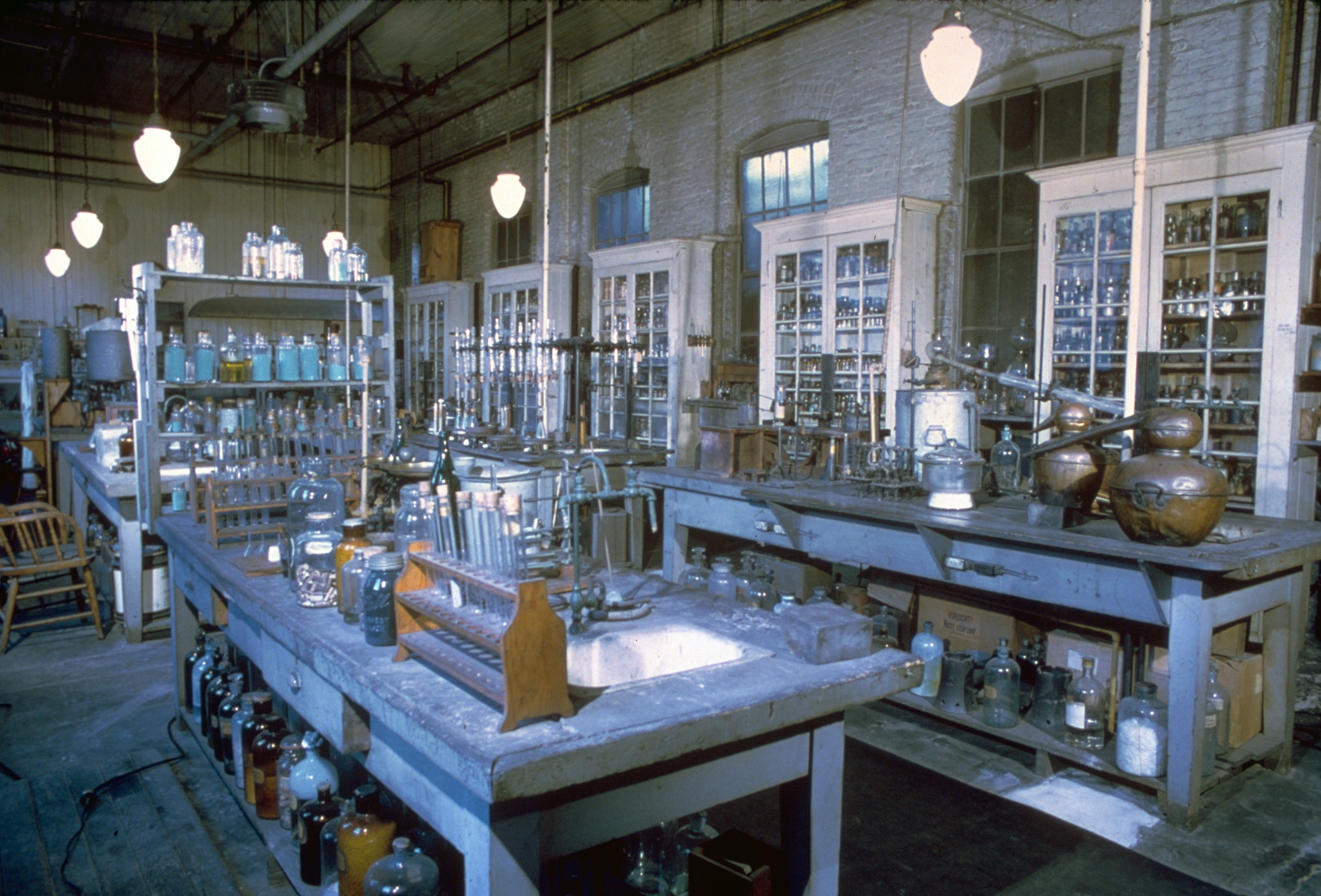

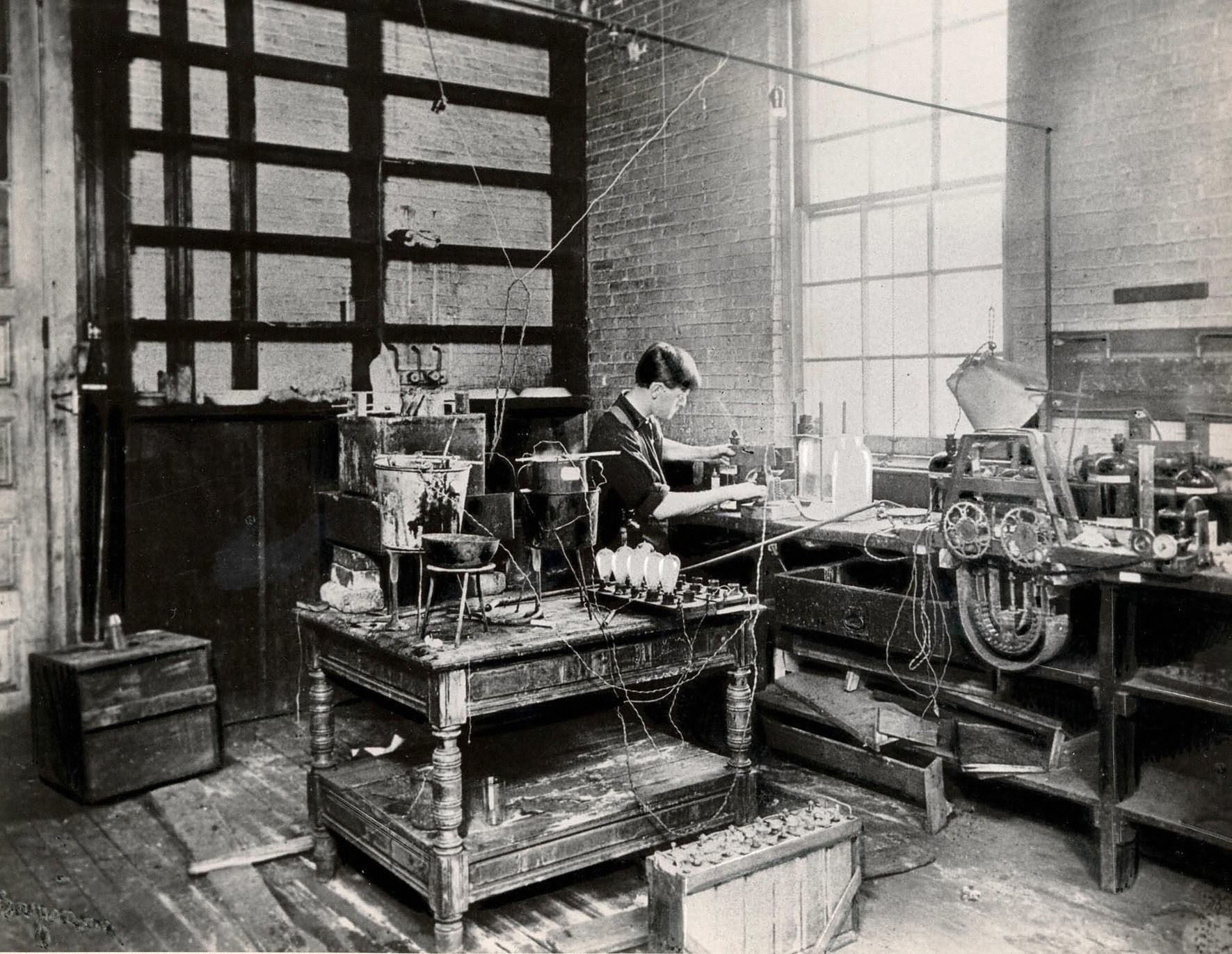

In 1886, Edison moved to Llewellyn Park, a residential area of West Orange, New Jersey, near New York City. Just blocks away, he built a laboratory 10 times the size of the one in Menlo Park. Edison envisioned the lab as a large-scale research facility for the industrial development of inventions.

The West Orange lab carried out chemical, mechanical, and electrical experiments. Edison added a staff of more than 50 experimenters, machinists, and draftsmen. The new lab also included a library with thousands of journals and books. Eventually, Edison’s research and development center included manufacturing plants.

Motion pictures.

Edison helped found the motion-picture industry. His interest seemed to take shape after he met Eadweard Muybridge, an English photographer. Like many people at the time, Muybridge was experimenting with photographing motion. In 1888, Edison envisioned a motion-picture device that “does for the Eye what the phonograph does for the Ear.” His assistant, W. K. L. Dickson, began to record a series of images on celluloid film. Showing the images in rapid succession made them look like continuous action.

Edison’s staff developed a camera and built the first film studio. In 1894, Edison’s company introduced a commercial device for viewing motion pictures, called the kinetoscope. It consisted of a cabinet with a peephole or eyepiece on top. A customer put a coin in the machine to watch a short motion picture through the hole. In 1896, Edison’s company introduced projectors designed by other inventors. The Great Train Robbery (1903), directed by Edwin S. Porter, ranks among the most notable films in the Edison catalog.

In the late 1800’s, Edison also began working on motion pictures that included sound. Dickson had experimented in this area, and other inventors were working on it. One problem was that the sound was not loud enough for large audiences to hear. In addition, getting the sound to match the images was difficult. Edison’s new version of the kinetophone—a combination kinetoscope and phonograph—debuted in 1913. It solved the problem of synchronizing (matching) the sound and images. The device used a pulley to attach a phonograph to a projector.

Edison and other inventors tried to control the motion-picture industry. In 1908, they formed the Motion Picture Patents Company. The company largely controlled the production, distribution, and exhibition of motion pictures in the United States. But in 1915, a federal court declared the company to be an illegal monopoly—that is, a business that unfairly controls the market for a product. Afterward, Edison and most other members of the Motion Picture Patents Company lost much of their influence in filmmaking.

Phonograph developments.

Edison exercised more direct control over his phonograph business than over his motion-picture business. He kept a close interest in the commercial and technical development of phonographs and recordings, especially when new competition emerged. Edison also set the general policies and strategies for his phonograph business. His guidelines determined which artists and tunes his company should record and release. The phonograph remained Edison’s favorite invention.

In the early 1900’s, the preferred format for sound recordings shifted from cylinders to flat discs. Discs were easier to mass produce and store than cylinders. Edison adopted the disc format in 1913. However, he continued to offer cylinder machines and recordings until 1929. The Ediphone, Edison’s dictating machine, was based on his cylinder phonograph.

Ore milling and cement.

In the late 1800’s, Edison planned a complete system for mining and refining iron ores. Steel mills in the eastern United States needed high-grade ore. Edison would crush low-grade ore and use electromagnets to separate the iron, thus making a concentrated ore for the mills. For this enterprise, Edison designed huge equipment and built a plant in New Jersey. At the plant, raw ore moved continuously on conveyor belts. The system resembled the assembly line later perfected by the American automaker Henry Ford.

Edison invested more than $1 million in ore milling. But the project ended in failure. Rich iron ore discovered in Minnesota proved cheaper to mine and process.

In the early 1900’s, Edison manufactured portland cement, a gray powder used to make concrete. The manufacturing plant made use of his iron ore project’s crushing and grinding technology and its large-scale mass-production techniques. Edison’s portland cement went into new bridges, highways, and buildings. More than 45,000 barrels of the cement were used to build the original Yankee Stadium in New York City. Edison also devised a way to build concrete houses quickly.

Batteries.

Edison had worked with batteries since his earliest days as a telegrapher. During the 1880’s and 1890’s, he experimented with lighter, more durable, and more powerful batteries. In the early 1900’s, Edison began to manufacture rechargeable storage batteries of a nickel-iron-alkaline design. He also set up a chemical plant to provide the materials. Edison batteries were used in electric trucks and automobiles and for electric starters in gasoline-powered cars. They were also used in railway cars, submarines , and mining lamps.

Final work.

During World War I (1914-1918), Edison headed the Naval Consulting Board, a group of inventors and business people who aided the war effort. He also faced manufacturing problems. They were caused by shortages of phenol, a chemical used in the production of phonograph records. During the 1920’s, Edison turned most of his businesses over to his son Charles. Edison continued to work and experiment while suffering from several illnesses in his later years. From the late 1920’s until the end of his life, Edison sought a natural substitute for rubber plants as a source of latex. He died at his home in Llewellyn Park on Oct. 18, 1931.

Personal life

Edison valued long, hard work. He believed that inventors should focus on practical projects that businesses or consumers would buy. “Genius is 1 percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration” is a quotation often associated with Edison—although Edison once wrote that he could not remember ever saying it.

Edison tried to learn from mistakes, but he was selective in admitting his errors. It was easy for him to learn something from a series of failed chemical tests. But he had difficulty admitting more serious mistakes. For example, Edison failed to appreciate the advantages of the Serbian engineer Nikola Tesla’s alternating current (AC) electric power system over his own direct current (DC) system. Direct current is an electric current that flows in only one direction. Alternating current, on the other hand, changes direction many times each second (see Electricity (Alternating and direct current) ).

Family and friends.

On Dec. 25, 1871, Edison married Mary Stilwell, who had worked in one of his companies. The couple had three children—Marion; Thomas Alva, Jr.; and William. Edison nicknamed Marion and Tom “Dot” and “Dash” after the telegraph code. Mary died in 1884.

In 1885, Edison met Mina Miller, the daughter of a wealthy Ohio industrialist. They married in 1886 and had three children—Madeleine, Charles, and Theodore. Of Edison’s six children, Charles became the most famous. He served as secretary of the U.S. Navy in 1940 and as governor of New Jersey from 1941 to 1944.

One of Edison’s most famous friends was Henry Ford. The industrial leaders became friends after Edison encouraged Ford to use gasoline engines in automobiles. The two friends later took automobile camping trips with the industrialist Harvey Firestone and the naturalist John Burroughs. The Edisons and the Fords also kept adjoining winter homes in Fort Myers, Florida .

Philosophy.

Always a man of many ideas, Edison stayed informed about technology, business, and current affairs. He had a down-to-earth manner and a frank opinion on most matters. Edison often expressed faith in progress and industry. He believed that mass production would bring a higher standard of living. He also believed that technology could solve social problems.

Honors.

Edison received honors from throughout the world. France appointed him to the Legion of Honor, its highest civilian award, in 1878. The U.S. Congress presented him with the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest honor it can give, in 1928. Henry Ford brought Edison much attention with an international celebration called “Light’s Golden Jubilee” in 1929. It honored Edison and the 50th anniversary of his incandescent lamp. In 2016, Ohio placed a statue of the inventor in Statuary Hall, a room in the U.S. Capitol that honors important people from each state.

A number of major historical sites and museums in the United States honor Edison. They include his birthplace in Milan, Ohio, and his winter home in Fort Myers, Florida. There is also the restored Menlo Park laboratory in Dearborn, Michigan. The Thomas Edison National Historical Park at West Orange, New Jersey, includes Edison’s laboratory and home.