Ammunition is any object fired or launched from a gun or some other weapon. Such objects, also called projectiles, include cartridges, shells, and rockets. Weapons that fire projectiles include handguns, cannons, and rocket launchers. Guided missiles and torpedos are also examples of ammunition, but this article does not discuss them. For information on these two kinds of ammunition, see the Guided missile and Torpedo articles.

Most kinds of ammunition contain a propellant, an explosive or a fuel that provides the force to send the projectile to its target. Nearly all ammunition also has a primer, a small amount of an explosive that detonates (explodes) and ignites the propellant. Some types of ammunition contain an additional explosive that shatters the projectile when it reaches the target, thus increasing the damage.

Ammunition can be classified into three types, according to its effects: (1) penetrators, (2) high explosives, and (3) carrier projectiles. Penetrators pierce targets using a single bullet. High explosives burst before hitting their target, fragmenting into thousands of penetrating pieces or becoming a high-speed jet of molten metal. Carrier projectiles break open near the target to deliver leaflets, radar-deceiving materials, or submunitions (small ammunition).

Ammunition can also be categorized by the kind of weapon from which it is fired. Categorized this way, the main types of ammunition are (1) small-arms, (2) artillery, and (3) armored-vehicle ammunition.

Small-arms ammunition

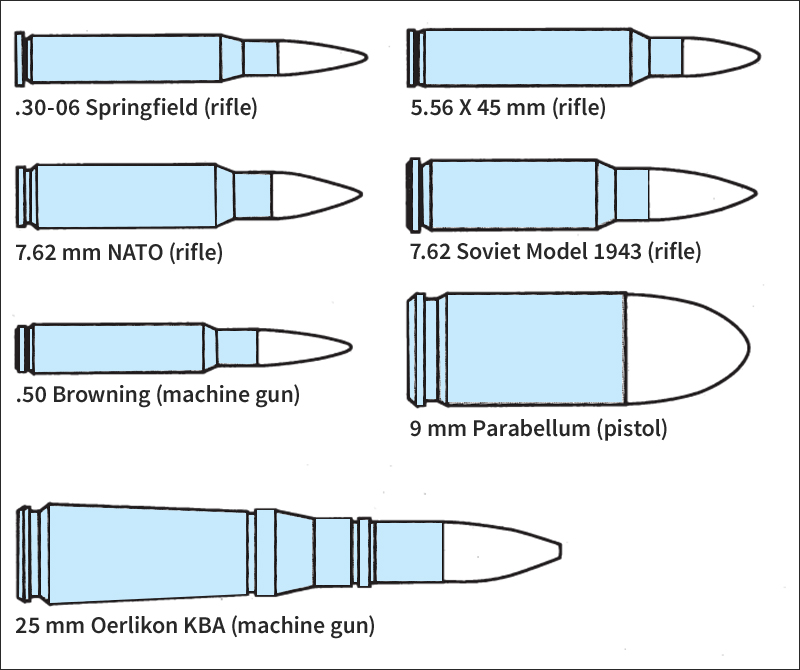

Small arms include light weapons such as pistols, rifles, and shotguns. Most kinds of small arms fire penetrators called cartridges. A single cartridge is known as a round.

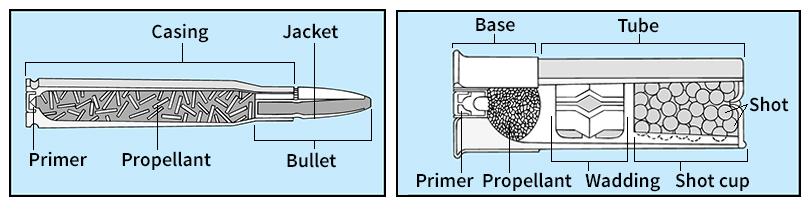

Cartridges are called fixed ammunition because they are manufactured as completely assembled units. Nearly all types of cartridges have a propellant, a primer, and a casing. However, cartridges differ in the type of projectile they contain. Most cartridges contain a bullet. Cartridges fired by shotguns hold metal pellets called shot.

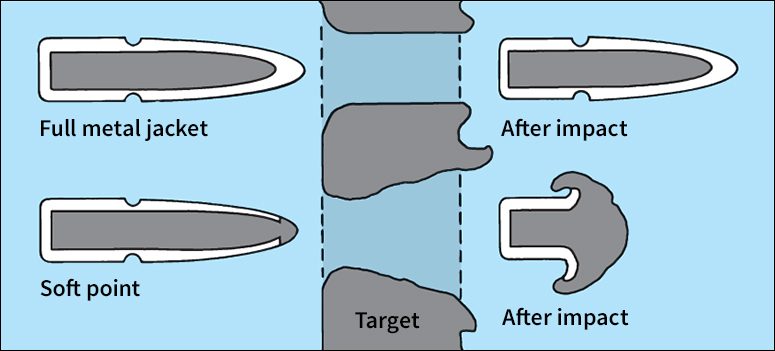

The bullet

is the projectile part of a cartridge. Most bullets have a steel or lead core covered by a jacket of hard metal. Some types of bullets expand when they strike their target, causing additional damage. International law forbids the military use of such bullets. Military forces use bullets that have a jacket of gilding metal, an alloy of copper and zinc that prevents expansion. Cartridges used in weapons other than shotguns are measured by caliber (the diameter of the bullet). Manufacturers and users of ammunition in the United States have traditionally specified caliber in decimal fractions of an inch. For example, a .30-caliber cartridge has a diameter of 30/100 inch (7.6 millimeters). However, it is becoming customary to use millimeters instead. The U.S. armed forces specify caliber in millimeters. Small-arms cartridges are less than 20 millimeters or .78 caliber.

The propellant

drives the bullet from the gun and propels it to the target. Propellants used in guns are called low explosives. Low explosives deflagrate (burn rapidly). This accelerates the bullet through the gun’s barrel. All small-arms ammunition has a propellant of smokeless powder, which consists of nitrocellulose or a mixture of nitrocellulose and nitroglycerin. This powder is also used in firing projectiles from cannons.

The primer

explodes when struck by the firing pin, a hammerlike device inside a gun. Lead styphnate is a common primer material.

The casing

holds the propellant and the primer and also grips the base of the projectile. It remains in the gun or falls out when the bullet is fired. Most casings are made of aluminum alloys or brass. Some cartridges have no casing. The propellant in caseless cartridges is molded to the base of the bullet. Cased, telescoped cartridges hide the bullet inside the propellant.

Shotgun cartridges

consist of a plastic or paper tube with a brass or steel case at one end. They contain lead or steel shot instead of bullets.

Riot control ammunition

is used by law enforcement officials to subdue rioters without causing serious injury. Most of this ammunition consists of hard rubber bullets. Another type is made of soft rubber rings that look like doughnuts and may contain tear gas. These rings cause less damage than do rubber bullets.

Artillery ammunition

Artillery includes rocket launchers and such mounted guns as howitzers, mortars, antiaircraft guns, and naval guns. Most types of field and naval artillery ammunition are called shells. A single shell, like a single cartridge, is known as a round. Field artillery projectiles range in size from tens of millimeters to a few hundred millimeters, and can weigh from a few pounds (1 kilogram) to hundreds of pounds (hundreds of kilograms). Most artillery shells taper to the rear, a shape that gives them greater range. Some have streamlined ogives (nose shields). Others, known as base-burner shells, have a small amount of propellant burning in the tail during flight. This reduces drag (air resistance).

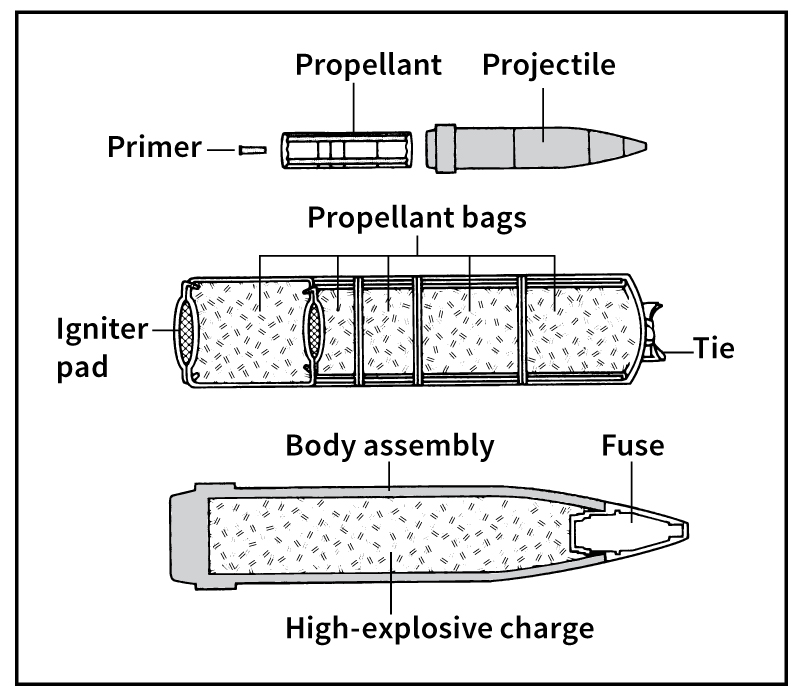

Some shells are high explosives, which detonate on impact and damage or destroy the target. Detonating the shell’s explosive filler shatters the shell into thousands of fragments. High explosives include TNT; RDX, also known as cyclonite or hexogen; composition B, a mixture of RDX and TNT; PETN; and pentolite, a combination of PETN and TNT. Other shells contain mines or small shells that can be expelled at intervals over a specified area or during a certain period of time.

Still other shells are filled with a nonexplosive substance, such as chemicals that are poisonous or that produce smoke or fire. Illuminating, or star, shells light up the battlefield or seascape. A shell with a chaff warhead expels strips of aluminum, which produce images on a radar screen similar to those caused by aircraft. Such images confuse radar operators and thus help protect aircraft from enemy attack.

There are five main types of artillery shells: (1) fixed ammunition; (2) semifixed ammunition; (3) separate loading, or bag, ammunition; (4) separated ammunition; and (5) guided ammunition. The word shell often refers not only to the entire unit of ammunition but also to the actual projectile part of the unit.

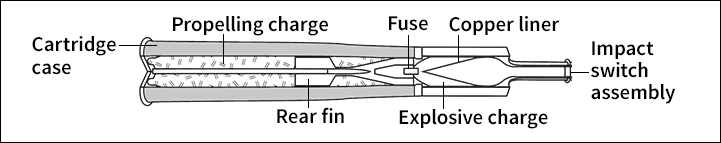

Fixed ammunition

fired by artillery consists of a projectile, a casing, a primer, and a propellant. Like small-arms cartridges, fixed artillery ammunition shells are manufactured as complete units.

Semifixed ammunition

resembles fixed ammunition. However, the projectile fits loosely into the casing so that the sections can be separated. Thus, the amount of propellant in the casing can be increased or decreased, depending on how far the shell is from the target.

Separate loading ammunition,

also called bag ammunition, consists of separate sections for the projectile, the primer, and the propellant. The propellant is packed into bags that are placed behind the projectile. The number of bags used depends on the distance the shell must travel. This type of ammunition is used to fire the heaviest artillery shells over great distances.

Separated ammunition

consists of two sections. One section is the projectile. The other includes the primer, the casing, and a fixed amount of propellant.

Guided ammunition

can correct its flight in the air after being fired. It often uses pop-out tail fins to steer itself. Most guided ammunition finds its target by tracking a laser spot on the target. This spot is usually produced by a forward observer, a person or object stationed ahead of the line of fire. Other types, known as smart shells, contain small radars and computers that can search for and find such targets as armored vehicles or trucks.

How shells explode.

A shell explodes by means of a process called the explosive train. This process consists of a series of explosions that detonate the shell after the projectile has been fired.

The explosive train begins with the explosion of the fuse (triggering device). The fuse may explode the instant the shell hits the target, or it may detonate a few seconds earlier or later. Some armor-piercing shells have a delayed fuse, which enables the projectile to penetrate before exploding. Most fuses operate mechanically or electronically. Mechanical fuses are activated by the movement of the shell during launch from the weapon, and the rotation of the shell as it travels through the air. Electronic proximity fuses are activated by devices inside the shell that often use radar waves to determine when the projectile is near the target.

In most shells, the fuse ignites the primer and thus sets off the first charge in the explosive train. Each successive charge in the process is more powerful than the previous one. The amount of force generated by the explosion of the charges increases until enough power has been created to detonate the main charge.

Armored-vehicle ammunition

Armored-vehicle ammunition consists of projectiles fired by guns mounted on tanks and other armored vehicles. They have diameters from 20 to 125 millimeters.

A common armored-vehicle penetrator is a projectile with a nose cap of tungsten or another heavy metal. The cap helps the projectile penetrate opposing vehicles. A high explosive projectile is a hollow-charge warhead. This warhead is hollow in the front and has an explosive charge in the back. Its explosion converts a copper cone in the warhead to a molten, high-speed jet. The jet penetrates the target. Another armored vehicle projectile is a long dart made of tungsten or depleted uranium (uranium with most of its radioactivity removed). The dart travels on a device called a sabot, which breaks away after the dart leaves the gun’s barrel.

History

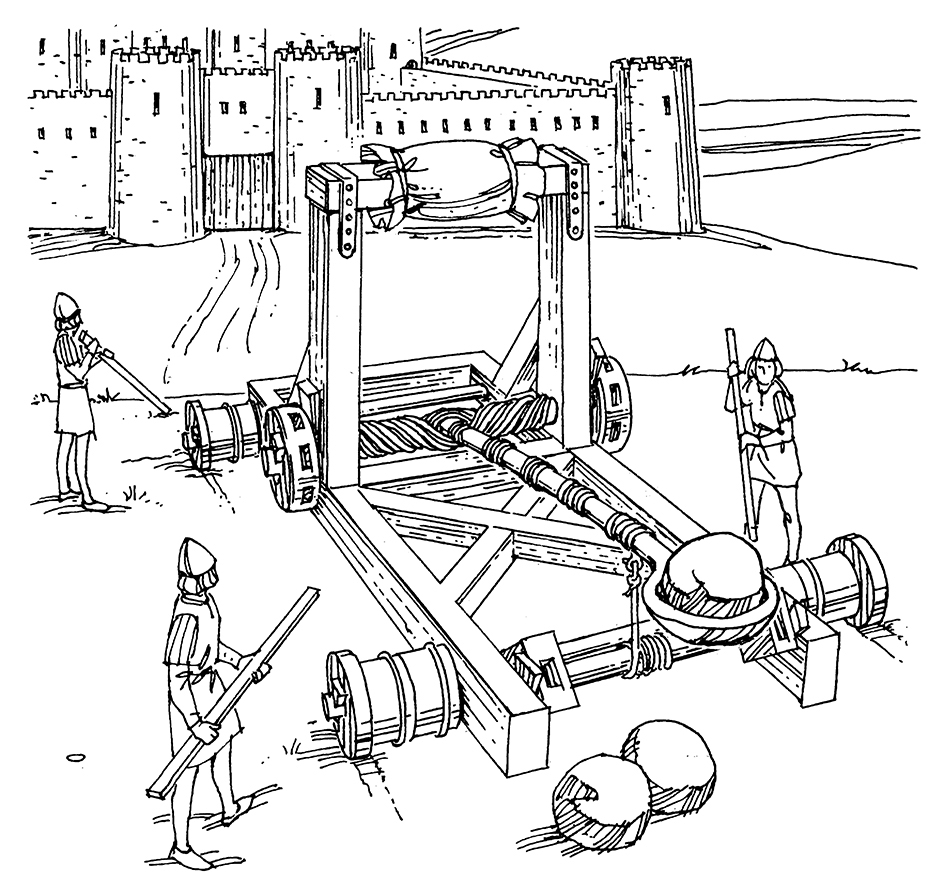

Stones, which people hurled from slings and other small weapons, were the first form of ammunition. The ancient Romans flung stones from huge siege weapons, such as the ballista and catapult. Arrows fired by longbows were effective ammunition against armored knights during the European Middle Ages (about the A.D. 400’s through the 1400’s). By the mid-1300’s, gunpowder was used to fire stones from cannons. By the 1400’s, iron and lead balls were also used as artillery ammunition.

During the 1400’s, people began to use handheld weapons that fired lead balls by the use of a trigger. By the 1500’s, the Dutch had developed powder-filled metal bombs that were fired from mortars. Cartridges became common in Europe in the early 1600’s. During the 1800’s, people began using paper fuses and shotguns that fired lead shot enclosed in paper shells. Smokeless powder also was invented in the 1800’s.

During World War I (1914-1918), high explosive shells, incendiary (fire-producing) bullets and shells, and chemical shells became common. In 1953, the United States Army fired the first shell with a nuclear charge. In the 1960’s and 1970’s, developments included the production of shells and cartridges made of plastics and lighter, stronger metals. Increasingly powerful propellants and more sophisticated guidance systems also came into use. In the 1980’s, weapons experts improved ammunition by increasing its range. Multiple-rocket launchers took the place of many big guns. Weapons experts continue to work on inventing more powerful projectiles that can disable several targets, such as an entire tank column, at once.