Fish are vertebrates (backboned animals) that live in water. There are more kinds of fish than all other kinds of water and land vertebrates put together. The various kinds of fish differ so greatly in shape, color, and size that it is hard to believe they all belong to the same group of animals. For example, some fish look like lumpy rocks, and others like wriggly worms. Some fish are nearly as flat as pancakes, and others can blow themselves up like balloons. Fish have all the colors of the rainbow. Many have colors as bright as the most brightly colored birds. Their rich reds, yellows, blues, and purples form hundreds of beautiful patterns, from stripes and lacelike designs to polka dots.

One of the world’s smallest fishes, the stout infantfish of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, grows only about 1/4 inch (7 millimeters) long. The largest fish is the whale shark, which may grow more than 40 feet (12 meters) long and weigh over 15 tons (14 metric tons). It feeds on tiny, drifting aquatic organisms called plankton and is completely harmless to most other fish and to human beings. The most dangerous fish weigh only a few pounds or kilograms. They include the deadly stonefish, whose stinging spines may kill a human being.

Fish live almost anywhere there is water. They are found in the near-freezing waters of the Arctic and in the warm waters of tropical jungles. Other fish live in roaring mountain streams and in peaceful underground rivers. Some fish make long journeys across the ocean. Others spend most of their life buried in sand on the bottom of the ocean. Most fish never leave water. Yet some fish are able to survive for months in dried-up riverbeds.

Fish have enormous importance to human beings. They provide food for millions of people. Fishing enthusiasts catch them for sport, and people keep them as pets. In addition, fish are important in the balance of nature. They eat plants and animals and, in turn, become food for other animals and provide nutrients for plants. Fish thus help keep in balance the total number of plants and animals on Earth.

All fish have two main features in common. (1) They have a backbone, and so they are vertebrates. (2) They breathe mainly by means of gills. Nearly all fish are also cold-blooded animals—that is, they cannot regulate their body temperature, which changes with the temperature of their surroundings. In addition, almost all fish have fins, which they use for swimming. All other water animals differ from fish in at least one of these ways. Dolphins, porpoises, and whales look like fish and have a backbone and fins, but they are mammals (animals that feed their young with the mother’s milk). Mammals breathe with lungs rather than gills. They are also warm-blooded—their body temperature remains about the same when the air or water temperature changes. Some water animals are called fish, but they do not have a backbone and so are not fish. These animals include jellyfish and starfish. Clams, crabs, lobsters, oysters, scallops, and shrimps are called shellfish. But they also lack a backbone.

Loading the player...Fish gills

The first fish appeared on Earth about 500 million years ago. They were the first animals to have a backbone. Most scientists think these early fish became the ancestors of all other vertebrates.

The importance of fish

Fish benefit people in many ways. Fish make up a major part of the people’s diet in Japan and Norway. In other countries, the people eat fish to add variety to their meals. For thousands of years, people have also enjoyed fishing for sport. Many people keep fish as pets. Fish are also important in the balance of nature.

Food and game fish.

Fish rank among the most nourishing of all foods. Fish flesh contains about as much protein as meat does. Each year, millions of tons of cod, herring, tuna, and other ocean food fish are caught commercially. Commercial fishing also takes place in inland waters, where such freshwater food fish as perch and trout are caught. The World Book article on Fishing industry discusses commercial fishing throughout the world.

Businesses called fish farms raise certain types of fish for food. Fish farms in the United States raise catfish, salmon, and trout. In other countries, they raise carp and milkfish. Fish farmers raise the fish in ponds and use special feeding methods to make the fish grow larger and faster than they grow in the wild.

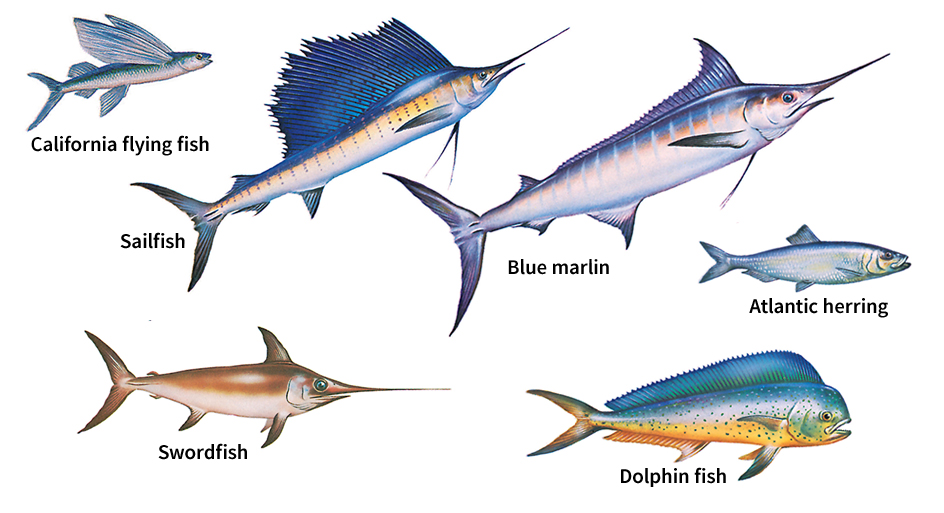

Some people enjoy fishing simply for fun. Many of these people like to go after game fish. Game fish are noted for their fighting spirit or some other quality that adds to the excitement of fishing. They include such giant ocean fish as marlin and sailfish and such freshwater fish as black bass and rainbow trout. Most game fish are also food fish. See the article on Fishing for detailed information on sport fishing.

Other useful fish.

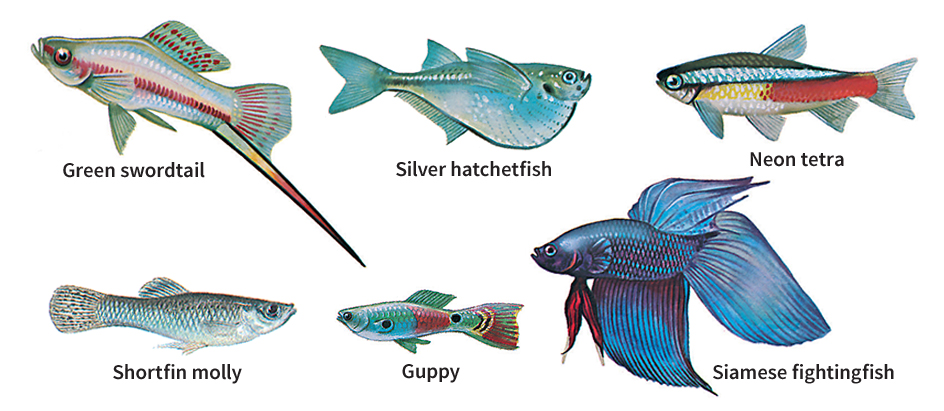

Certain fish, such as anchovetas and menhaden, are caught commercially but are not good to eat. Industries process these fish to make glue, livestock feed, and other products. Scientists often use goldfish and other small fish as experimental animals in medical research. They do not require as much space or as much care as do other experimental animals. Some fish produce substances used as medicines. For example, a chemical produced by puffers is used to treat asthma. Many people enjoy keeping fish as pets in home aquariums (see Aquarium, Home). Popular aquarium fish include goldfish, guppies, and tetras.

Harmful fish.

Few species of fish will attack a human being. They include certain sharks, especially tiger sharks and great white sharks, which occasionally bite swimmers. Barracudas and moray eels may also attack a swimmer if provoked. Certain types of piranhas are bloodthirsty fish with razor-sharp teeth. A group of them can strip the flesh from a large mammal in minutes. Some other fish, including stingrays and stonefish, have stinging spines that can injure or kill anything that tries to eat them. The flesh of filefish, puffers, and some other fish is poisonous and can cause sickness or death if eaten.

Loading the player...Scrawled filefish

Many species of fish have become pests after being introduced into certain waters. For example, sea lampreys that entered the Great Lakes and Asian catfish introduced into inland waters of Florida have become threats to native fish.

Fish in the balance of nature.

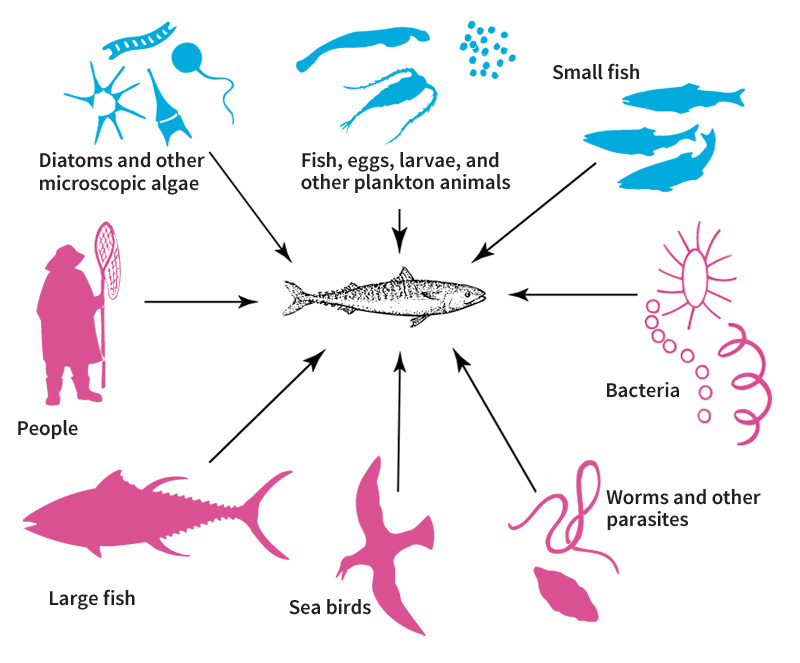

All the fish in a particular environment, such as a lake or a certain area of the ocean, make up a fish community. The fish in a community are part of a system in which energy is transferred from one living thing to another in the form of food. Such a system is called a food chain.

Nearly all food chains begin with the energy from sunlight. Plants and other photosynthetic organisms use this energy to make their food. In the ocean and in fresh water, the most important kinds of life are part of the plankton–the great mass of tiny organisms that drifts near the surface. Certain fish eat plankton and are in turn eaten by other fish. These fish may then be eaten by still other fish. Some of these fish may also be eaten by people or by birds or other animals. Many fish die naturally. Their bodies then sink and decay. The decayed matter provides nourishment for water plants, animals, and other organisms.

Every fish community forms part of a larger natural community made up of all the organisms in an area. A natural community includes numerous food chains, which together are called a food web. The complicated feeding patterns involved in a food web keep any one form of life from becoming too numerous and so preserve the balance of nature.

The balance of a community may be upset if large numbers of one species in the community are destroyed. People may upset the balance in this way by catching too many fish of a particular kind. Or they may pollute the water so badly that certain kinds of aquatic life, including certain fish, can no longer live in it. To learn how people conserve fish, see Fishing industry (Fishery conservation).

Kinds of fish

Scientists have named and described more than 35,000 kinds of fishes. Each year, they discover new species, and so the total increases continually. Fish make up more than half of all known species of vertebrates.

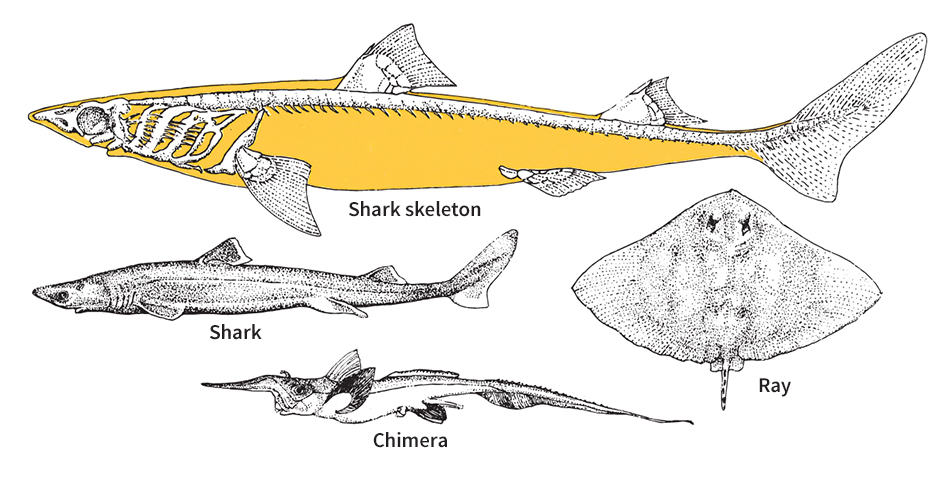

Scientists who study fish are called ichthyologists << `ihk` thee OL uh jihsts >>. They divide fish into two main groups: (1) jawed and (2) jawless. Almost all fish have jaws. The only jawless species are lampreys and hagfish. Jawed fish are further divided into two groups according to the composition of their skeletons. One group has a skeleton composed of a tough, elastic substance called cartilage. Sharks, rays, and chimaeras make up this group. The other group has a skeleton composed largely or partly of bone. Members of this group, called bony fish, make up by far the largest group of fish in the world.

The section of this article called A classification of fish lists the major subgroups into which bony fish are divided. This section discusses the chief characteristics of (1) bony fish; (2) sharks, rays, and chimaeras; and (3) lampreys and hagfish.

Bony fish

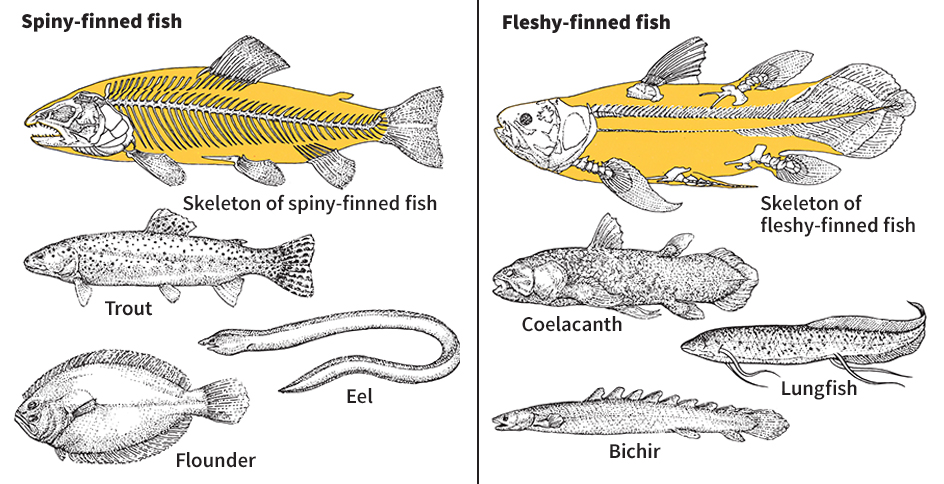

Bony fish can be divided into two main groups. One group has bony rays to support their fins. These fish, called spiny-finned fish, include most modern species. The other group, the fleshy-finned fish, have more fleshy fins than do spiny-finned fish.

Spiny-finned fish

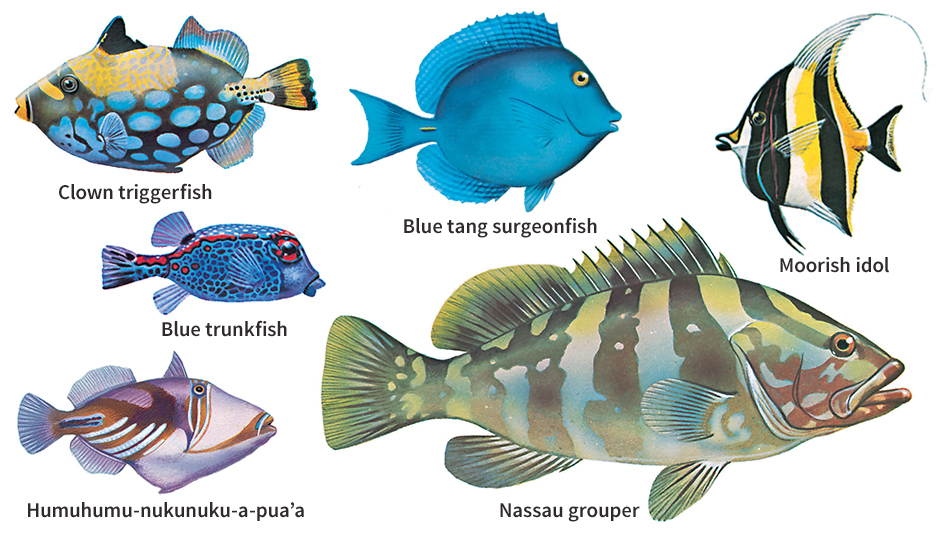

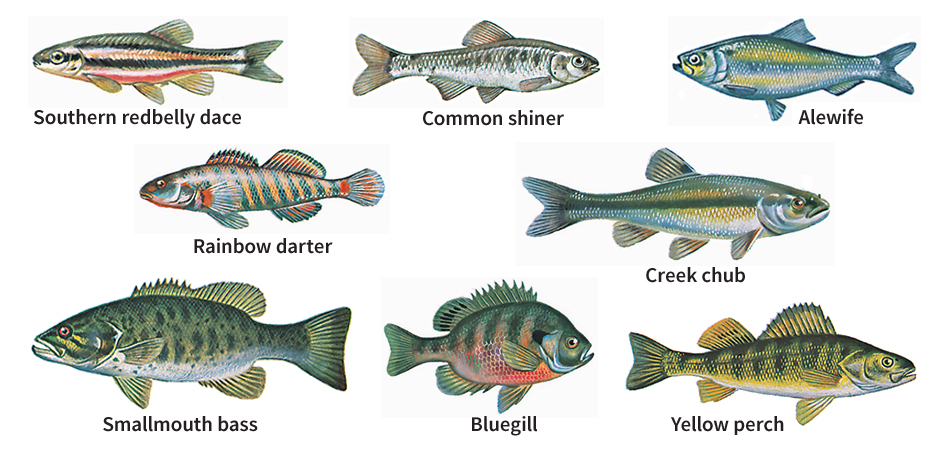

include about 23,000 species. They make up about 95 percent of all known kinds of fish. Some have bony skeletons. They are called teleosts, which comes from two Greek words meaning complete and bone. Nearly all food fish, game fish, and aquarium fish are teleosts. They include such well-known groups of fish as bass, catfish, cod, herring, minnows, perch, trout, and tuna. Each group of fish consists of a number of species. For example, Johnny darters, walleyes, and yellow perch are all kinds of perch.

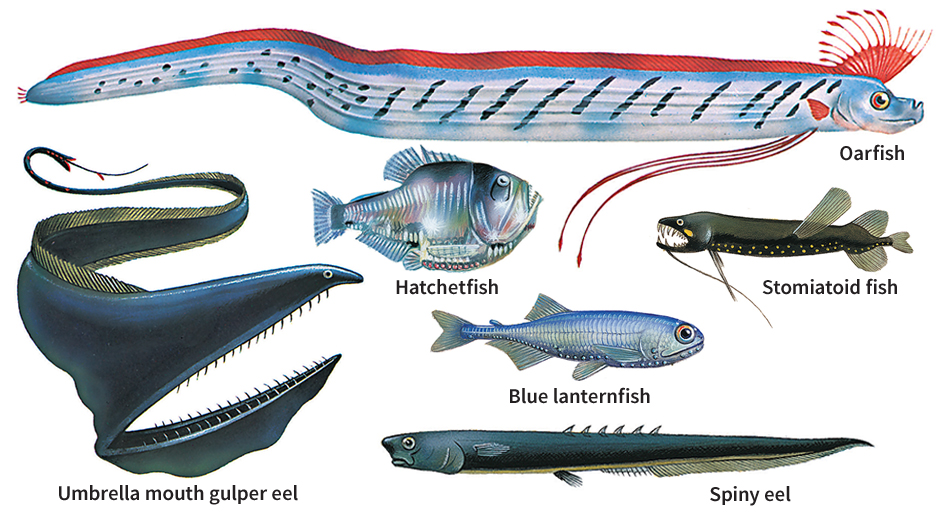

Thousands of species of teleosts are not so well known. A large number live in jungle rivers or coral reefs. Some are deep-sea species seldom seen by human beings. They include more than 150 kinds of deep-sea anglers. These small, fierce-looking fish have fanglike teeth and glowing light organs. Deep-sea anglers live in the ocean depths and seldom if ever come to the surface.

Many teleosts have unusual names and are as strange and colorful as their names. For example, the elephant-nose mormyrid has a snout shaped much like an elephant’s trunk. The fish uses its snout to hunt for food along river bottoms. Another strange fish, the upside-down catfish, regularly swims on its back.

Many millions of years ago, there were only a few species of teleosts. They were greatly outnumbered by sharks and the ancestors of certain present-day bony fish. The early teleosts looked much alike and lived in only a few parts of the world. Yet they became the most numerous, varied, and widespread of all fish mainly because they were better able than other fish to adapt (adjust) to changes in their environment. In adapting to these changes, their bodies and body organs changed in various ways. Such changes are called adaptations.

Today, the various species of teleosts differ from one another in so many ways that they seem to have little in common. For example, many teleosts have flexible, highly efficient fins, which have helped them become excellent swimmers. Sailfish and tuna can swim long distances at high speed. Many teleosts that live among coral reefs are expert at darting in and out of the coral. But a number of other teleosts swim hardly at all. Some anglerfish spend most of their adult life lying on the ocean floor. Certain eellike teleosts are finless and so are poor swimmers. They burrow into mud on the bottom and remain there much of the time. A large number of teleosts have fins that are adapted to uses other than swimming. For example, flyingfish have winglike fins that help them glide above the surface of the water. The mudskipper has muscular fins that it uses to hop about on land.

Other bony fish include sturgeons, paddlefish, gars, and bowfins. Sturgeons rank as the largest of all freshwater fish. The largest sturgeon ever caught weighed more than 4,500 pounds (2,040 kilograms). Instead of scales, sturgeons have an armorlike covering consisting of five rows of thick, bony plates. Some sturgeons live in salt water but return to fresh water to lay their eggs. Paddlefish are strange-looking fish found only in the Mississippi Valley of the United States. They have huge snouts shaped somewhat like canoe paddles. Bowfins and gars are extremely fierce fish of eastern North America. They have unusually strong jaws and sharp teeth.

Fleshy-finned fish

include the coelacanth and six species of lungfish. They make up less than 1 percent of all fish species. These odd-looking fish are related to fish that lived many millions of years ago.

All the fleshy-finned bony fish except the coelacanth live in fresh water. Coelacanth live off the southeastern coast of Africa. They are not closely related to any other living fish, and there is only one known species of coelacanth.

Lungfish live in Africa, Australia, and South America. They breathe with lunglike organs as well as gills. The African and South American species can go without food and water longer than any other vertebrates. They live buried in dry mud for months at a time, during which they neither eat nor drink.

Sharks, rays, and chimaeras

Sharks, rays, and chimaeras total about 965 species, or about 4 percent of all known fish. All of these species have jaws and a skeleton of cartilage rather than bone. Almost all live in salt water. Sharks and rays are the most important members of the group and make up about 925 species.

Most sharks have a torpedo-shaped body. The bodies of most rays are shaped somewhat like pancakes. A large, winglike fin extends outward from each side of a ray’s flattened head and body. But the angel shark has a flattened body, and the sawfish and a few other rays are torpedo shaped. As a result, the best way to tell a shark from a ray is by the position of the gill slits. In sharks and rays, gill slits are slotlike openings on the outside of the body, leading from the gills. A shark’s gill slits are on the sides of its head just back of the eyes. A ray’s are underneath its side fins.

Chimaeras, or ratfish, include about 40 species. They are medium-sized fish with large eyes and a long, slender, pointed tail. They live near the ocean bottom. Several species have long, pointed snouts.

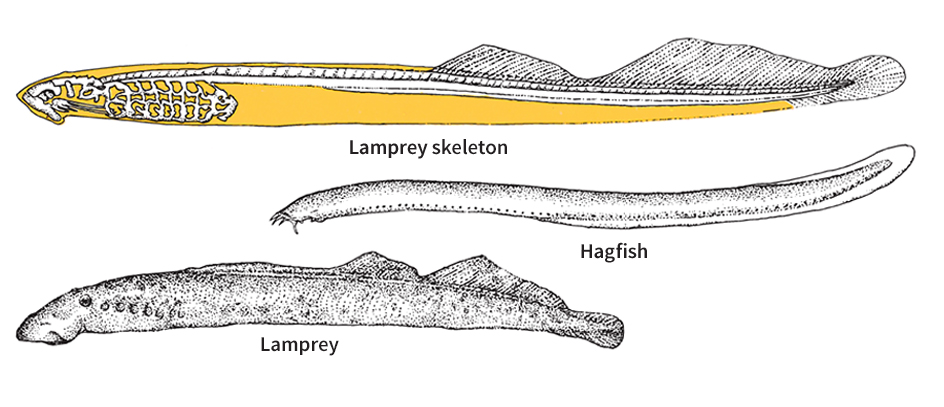

Lampreys and hagfish

Lampreys and hagfish are the most primitive of all fish. There are about 40 species of lampreys and about 50 species of hagfish. They make up less than 1 percent of all fish species. Lampreys live in both salt water and fresh water. Hagfish live only in the ocean.

Lampreys and hagfish have slimy, scaleless bodies shaped somewhat like the bodies of eels. But they are not closely related to eels, which are teleosts. Like sharks, rays, and chimaeras, lampreys and hagfish have a skeleton made of cartilage. But unlike all other fish, lampreys and hagfish lack jaws. A lamprey’s mouth consists mainly of a round sucking organ and a toothed tongue. Certain types of lampreys use their sucking organ to attach themselves to other fish. They use their toothed tongue to cut into their victim and feed on its blood. Hagfish have a slitlike mouth with sharp teeth but no sucking organ. They eat the insides of dead fish.

Where fish live

Fish live almost anywhere there is water. They thrive in the warm waters of the South Pacific and in the icy waters of the Arctic Ocean and the Southern Ocean, which surrounds Antarctica. Some live high above sea level in mountain streams. Others live far below sea level in the deepest parts of the ocean. Many fish have adapted themselves to living in such unusual places as caves, desert water holes, marshes, and swamps. A few fish, including the African and South American lungfish, can live for months in moist mud.

Fish thus live in many environments. But all these environments can be classified into two major groups according to the saltiness of the water: (1) saltwater environments and (2) freshwater environments. Some fish can live only in the salty waters of the ocean. Others can live only in fresh water. Still others can live in either salt water or fresh water. The sections on The bodies of fish and How fish live discuss how fish adjust to their environment. This section describes some of the main saltwater and freshwater environments. It also discusses fish migrations from one environment to another. A series of illustrations shows the kinds of fish that live in the various environments. The illustration for each fish gives the fish’s common and scientific names and the average or maximum length of an adult fish.

Saltwater environments.

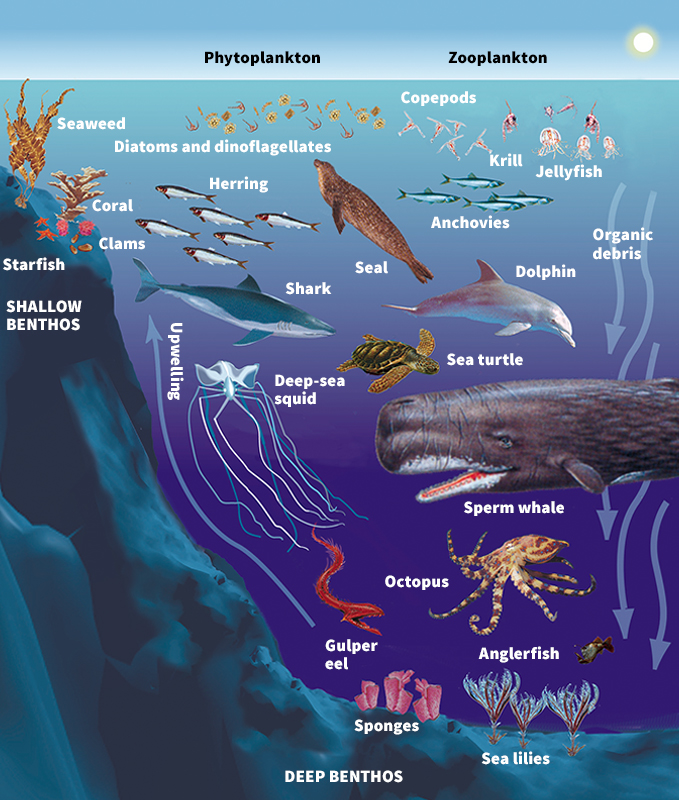

About 20,000 species of fish live in salt water. Ocean, or marine, fish live in an almost endless variety of ocean environments. Most of them are suited to a particular type of environment and cannot survive in one much different from that type. Water temperature is one of the chief factors in determining where a fish can live. Water temperatures at the surface range from freezing in polar regions to about 86 °F (30 °C) in the tropics.

Many saltwater species live where the water is always warm. The warmest parts of the ocean are the shallow tropical waters around coral reefs. More than a third of all known saltwater species live around coral reefs in the Indian and Pacific oceans. Many other species live around reefs in the Caribbean Sea. Coral reefs swarm with angelfish, butterflyfish, parrotfish, and thousands of other species with fantastic shapes and brilliant colors. Barracudas, groupers, moray eels, and sharks prowl the clear coral waters in search of prey.

Loading the player...Spotfin butterflyfish

Many kinds of fish also live in ocean waters that are neither very warm nor very cold. Such temperate waters occur north and south of the tropics. They make excellent fishing grounds, especially off the western coasts of continents. In these areas, nutrient-rich water comes up from the depths and supports the plankton that, in turn, supports enormous quantities of anchovies, herrings, sardines, and other food fish.

The cold waters of the Arctic and Southern oceans have fewer kinds of fish than do tropical and temperate waters. Arctic fish include bullheads, eelpouts, sculpins, skates, and a jellylike, scaleless fish called a sea snail. Fish of the Southern Ocean include the small, perchlike Antarctic cod, eelpouts, and the icefish, whose blood is nearly transparent rather than red.

Different kinds of fish also live at different depths in the ocean. The largest and fastest-swimming fish live near the surface of the open ocean and are often found great distances from shore. Fish that live near the surface of the open ocean include bonito, mackerel, marlin, swordfish, tuna, and a variety of sharks. Some of these fish make long annual migrations that range from tropical to near-polar waters.

Many more kinds of ocean fish live in midwater and in the depths than near the surface. Their environment differs greatly from that of species which live near the surface. Sunlight cannot reach far beneath the ocean’s surface. Below about 600 feet (180 meters), the waters range from dimly lit to completely dark. Most fish that live in midwater far out at sea measure less than 6 inches (15 centimeters) long and are black, black-violet, or reddish-brown. Most of them have light organs that flash on and off in the darkness. Many also have large eyes and mouths. A number of midwater species are related to the herring. One such group includes the tiny bristlemouths. Scientists think there are more bristlemouths than any other kind of fish. They estimate that bristlemouths number in the trillions.

Some fish species live on the ocean bottom. Many of these fish, such as eels, flounders, puffers, seahorses, and soles, live in shallow coastal waters. But many others live at the bottom far from shore. They include rattails and many other fish with large heads and eyes and long, slender, pointed tails. Many species of rattails grow 1 foot (30 centimeters) or more long. One of the strangest bottom dwellers of the deep ocean is the tripod, or spider, fish. It has three long fins like the legs of a tripod or a three-legged stool. The fish uses its fins to sit on the ocean bottom.

Some kinds of fish live in brackish (slightly salty) water. Such water occurs where rivers empty into the ocean, where salt water collects in coastal swamps, and where pools are left by the outgoing tide. Brackish-water fish include certain species of barracudas, flatfish, gobies, herring, killifish, silversides, and sticklebacks. Some saltwater fish, including various kinds of herring, lampreys, salmon, smelt, and sticklebacks, can also live in fresh water.

Freshwater environments.

Fish live on every continent except Antarctica. They are found in most lakes, rivers, and streams and in brooks, creeks, marshes, ponds, springs, and swamps. Some live in streams that pass through caves or flow deep underground.

Scientists have identified more than 18,000 kinds of fish that live in fresh water. Almost all freshwater fish are bony fish. Many of these bony fish belong to a large group that includes carp, catfish, characins, electric eels, loaches, minnows, and suckers. In this group, catfish alone total more than 4,000 species.

Like ocean fish, freshwater fish live in a variety of climates. Tropical regions of Africa, Asia, and South America have the most species, including hundreds of kinds of catfish. Africa also has many cichlids and mormyrids. A variety of colorful loaches and minnows live in Asia. South American species include electric eels, piranhas, and tetras. Temperate regions, especially in North America, also have many freshwater species, including bass, carp, minnows, perch, and trout. Blackfish and pike live in the Arctic.

In every climate, certain kinds of freshwater fish require a particular kind of environment. Some species, including many kinds of graylings, minnows, and trout, live mainly in cool, clear, fast-moving streams. Many species of carp and catfish thrive in warm, muddy, slow-moving rivers. Some fish, such as bluegills, lake trout, white bass, and whitefish, live chiefly in lakes. Black bullheads, largemouth bass, muskellunge, northern pike, rainbow trout, yellow perch, and many other species are found both in lakes and in streams and rivers.

Like marine fish, freshwater fish live at different levels in the water. For example, many cave, spring, and swamp fish live near the surface. Gars, muskellunge, and whitefish ordinarily live in midwater. Bottom dwellers include darters, sturgeon, and many kinds of catfish and suckers.

Some freshwater species live in unusual environments. For example, some live in mountain streams so swift and violent that few other forms of life can survive in them. These fish cling to rocks with their mouth or some special suction organ. A number of species live in caves and underground streams. These fish never see daylight. Most of them have pale or white skin, and many of them are blind. A few kinds of freshwater fish live in hot springs where the temperature rises as high as 104 °F (40 °C).

Fish migrations.

Relatively few kinds of fish can travel freely between fresh water and salt water. They make such migrations to spawn (lay eggs). Saltwater fish that swim to fresh water for spawning are called anadromous fish. They include alewives, blueback herring, sea lampreys, smelt, and most species of salmon and shad. Freshwater fish that spawn in salt water are called catadromous fish. They include North American and European eels and certain kinds of gobies. Some normally anadromous fish, including large numbers of certain species of alewives, lampreys, salmon, and smelt, have become landlocked—that is, they have become freshwater natives. After hatching, the young do not migrate to the ocean. The section How fish adjust to change explains why most fish cannot travel freely between salt water and fresh water.

Many saltwater species migrate from one part of the ocean to another at certain times of the year. For example, many kinds of mackerel and certain other fish of the open ocean move toward shore to spawn. Each summer, many species of haddock and other cold-water fish migrate from coastal waters to cooler waters farther out at sea. Some freshwater fish make similar migrations. For example, some trout swim from lakes into rivers to spawn. Some other fish of temperate lakes and streams, such as bass, bluegills, and perch, live near the warm surface during summer. When winter comes, the waters freeze at the surface but remain slightly warmer beneath the ice. The fish then migrate toward the bottom and remain there until warm weather returns.

The bodies of fish

In some ways, a fish’s body resembles that of other vertebrates. For example, fish, like other vertebrates, have an internal skeleton, an outer skin, and such internal organs as a heart, intestines, and a brain. But in a number of ways, a fish’s body differs from that of other vertebrates. For example, fish have fins instead of legs, and gills instead of lungs. Lampreys and hagfish differ from all other vertebrates—and from all other fish—in many ways. Their body characteristics are discussed in an earlier section on Lampreys and hagfish. This section deals with the physical features that most other fish have in common.

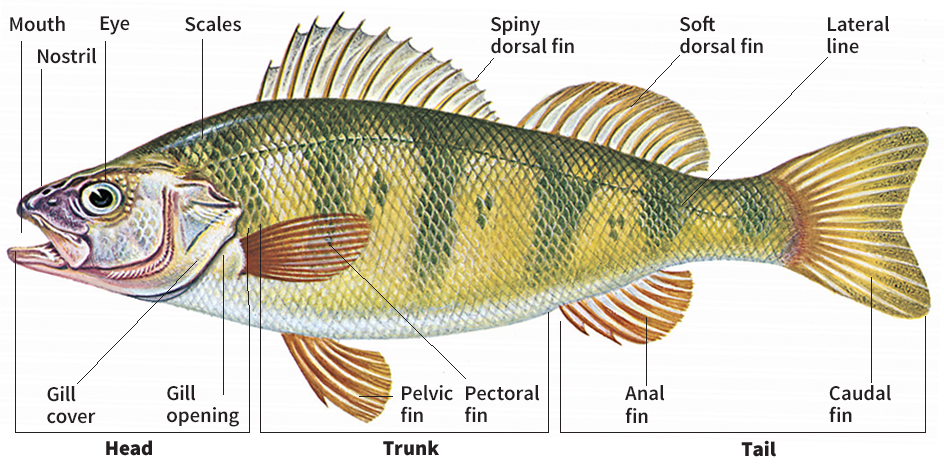

External anatomy

Shape.

Most fish have a streamlined body. The head is somewhat rounded at the front. Fish have no neck, and so the head blends smoothly into the trunk. The trunk, in turn, narrows into the tail. Aside from this basic similarity, fish have a variety of shapes. Tuna and many other fast swimmers have a torpedolike shape. Herring, freshwater sunfish, and some other species are flattened from side to side. Many bottom-dwelling fish, including most rays, are flattened from top to bottom. A number of species are shaped like things in their surroundings. For example, anglerfish and stonefish resemble rocks, and pipefish look like long, slender weeds. This camouflage, called protective resemblance, helps a fish escape the notice of its enemies and its prey.

Skin and color.

Most fish have a fairly tough skin. It contains blood vessels, nerves, and connective tissue. It also contains certain special cells. Some of these cells produce a slimy mucus. This mucus makes fish slippery. Other special cells, called chromatophores or pigment cells, give fish many of their colors. A chromatophore contains red, yellow, or brownish-black pigments. These colors may combine and produce other colors, such as orange and green. Some species have more chromatophores of a particular color than other species have or have their chromatophores grouped differently. Such differences cause many variations in coloring among species. Besides chromatophores, many fish also have whitish or silvery pigments in their skin and scales. In sunlight, these pigments produce a variety of bright rainbow colors.

The color of most fish matches that of their surroundings. For example, most fish that live near the surface of the open ocean have a blue back, which matches the color of the ocean surface. This type of camouflage is called protective coloration. But certain brightly colored fish, including some that have stinging spines, do not blend with their surroundings. Bright colors may protect a fish by confusing its enemies or by warning them that it has stinging spines or poisonous flesh.

Many fish can change their color to match color changes that are present in their surroundings. Flatfish and some other fish that have two or more colors can also change the pattern formed by their colors. A fish receives the impulse to make such changes through its eyes. Signals from a fish’s nerves then rearrange the pigments in the chromatophores to make them darker or lighter. The darkening or lightening of the chromatophores produces the different color patterns.

Scales.

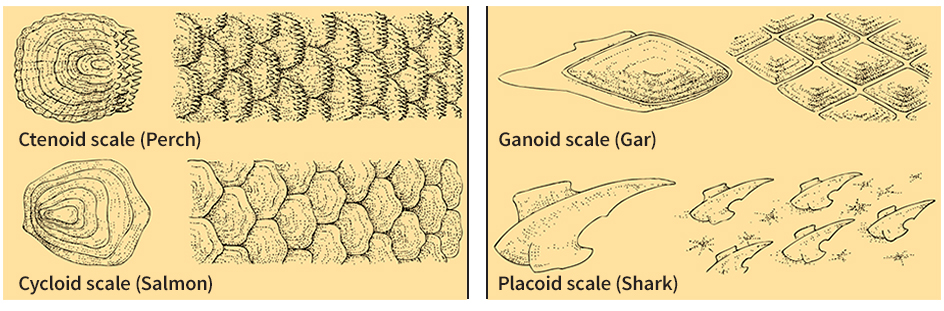

Most jawed fish have a protective covering of scales. Teleost fish have thin, bony scales that are rounded at the edge. There are two main types of teleost scales—ctenoid and cycloid. Ctenoid scales have tiny points on their surface. Fish that feel rough to the touch, such as bass and perch, have ctenoid scales. Cycloid scales have a smooth surface. They are found on such fish as carp and salmon. Some bony fish, including bichirs and gars, have thick, heavy ganoid scales. Sharks and most rays are covered with placoid scales, which resemble tiny, closely spaced teeth. Some fish, including certain kinds of eels and freshwater catfish, are scaleless.

Fins

are movable structures that help a fish swim and keep its balance. A fish moves its fins by means of muscles. Except for a few finless species, all spiny-finned bony fish have rayed fins. These fins consist of a web of skin supported by a skeleton of rods called rays. Some ray-finned fish have soft rays. Others have both soft rays and rays which are stiff and sharp to the touch. Fleshy-finned bony fish commonly have lobed fins, which consist of a fleshy base fringed with rays. Lobed fins are less flexible than rayed fins. Sharks, rays, and chimaeras have fleshy, skin-covered fins supported by numerous fine rays made of a tough material called keratin.

Fish fins are classified according to their position on the body as well as according to their structure. Classified in this way, a fin is either median or paired.

Median fins are vertical fins on a fish’s back, underside, or tail. They include dorsal, anal, and caudal fins. The dorsal fin grows along the back and helps a fish keep upright. Almost all fish have at least one dorsal fin, and many have two or three. The anal fin grows on the underside. Like a dorsal fin, it helps a fish remain upright. Some fish have two anal fins. The caudal fin is at the end of the tail. A fish swings its caudal fin from side to side to propel itself through the water and to help in steering.

Paired fins are two identical fins, one on each side of the body. Most fish have both pectoral and pelvic paired fins. The pectoral, or shoulder, fins of most fish grow on the sides, just back of the head. Most fish have their pelvic, or leg, fins just below and behind their pectoral fins. But some have their pelvic fins as far forward as the throat or nearly as far back as the anal fin. Pelvic fins are also called ventral fins. Most fish use their paired fins mainly to turn, stop, and make other maneuvers.

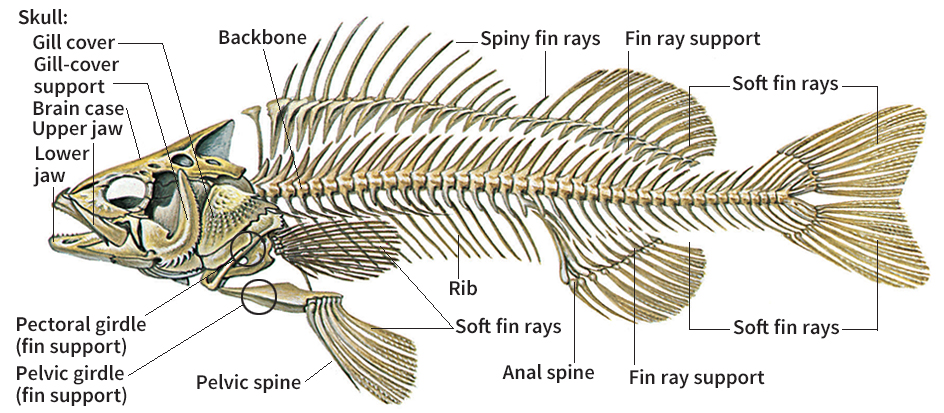

Skeleton and muscles

A fish’s skeleton provides a framework for the head, trunk, tail, and fins. The central framework for the trunk and tail is the backbone. It consists of many separate segments of bone or cartilage called vertebrae. In bony fish, each vertebra has a spine at the top, and each tail vertebra also has a spine at the bottom. Ribs are attached to the vertebrae. The skull consists chiefly of the brain case and supports for the mouth and gills. The pectoral fins of most fish are attached to the back of the skull by a structure called a pectoral girdle. The pelvic fins are supported by a structure called a pelvic girdle which is attached to the pectoral girdle or supported by muscular tissue in the abdomen. The dorsal fins are supported by structures of bone or cartilage, which are rooted in tissue above the backbone. The caudal fin is supported by the tail, and the anal fin by structures of bone or cartilage below the backbone.

Like all vertebrates, fish have three kinds of muscles: (1) skeletal muscles, (2) smooth muscles, and (3) heart muscles. Fish use their skeletal muscles to move their bones and fins. A fish’s flesh consists almost entirely of skeletal muscles. They are arranged one behind the other in broad vertical bands called myomeres. The myomeres can easily be seen in a skinned fish. Each myomere is controlled by a separate nerve. As a result, a fish can bend the front part of its body in one direction while bending its tail in the opposite direction. Most fish make such movements with their bodies to swim. A fish’s smooth muscles and heart muscles work automatically. The smooth muscles are responsible for operating such internal organs as the stomach and intestines. Heart muscles form and operate the heart.

Systems of the body

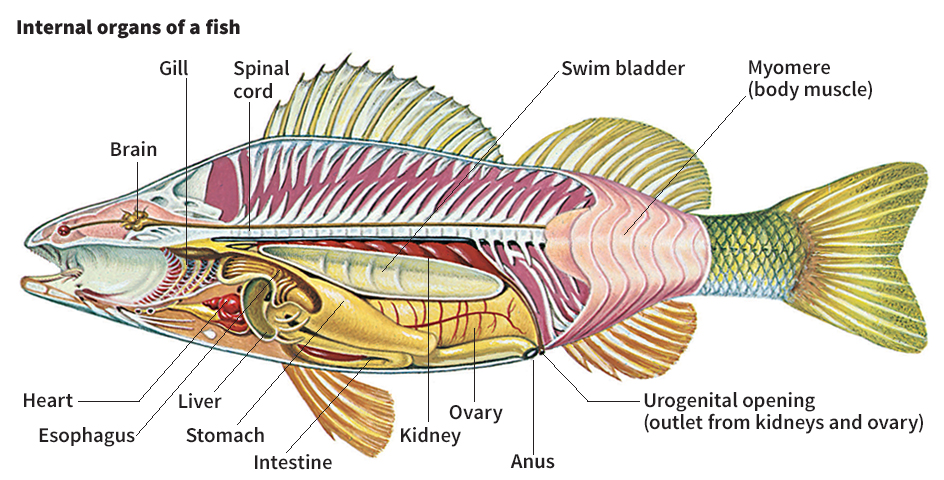

The internal organs of fish, like those of other vertebrates, are grouped into various systems according to the function they serve. The major systems include the respiratory, digestive, circulatory, nervous, and reproductive systems. Some of these systems resemble those of other vertebrates, but others differ in many ways.

Respiratory system.

Unlike land animals, almost all fish get their oxygen from water. Water contains a certain amount of dissolved oxygen. To get oxygen, fish gulp water through the mouth and pump it over the gills. Most fish have four pairs of gills enclosed in a gill chamber on each side of the head. Each gill consists of two rows of fleshy filaments attached to a gill arch. Water passes into the gill chambers and flows over the gills. A flap of bone called a gill cover protects the gills of bony fish. Sharks and rays do not have gill covers. Their gill slits form visible openings on the outside of the body.

In a bony fish, the breathing process begins when the gill covers close and the mouth opens. At the same time, the walls of the mouth expand outward, drawing water into the mouth. The walls of the mouth then move inward, the mouth closes, and the gill covers open. This action forces the water from the mouth into the gill chambers. In each chamber, the water passes over the gill filaments. They absorb oxygen from the water and replace it with carbon dioxide formed during the breathing process. The water then passes out through the gill openings, and the process is repeated.

Digestive system,

or digestive tract, changes food into materials that nourish the body cells. It eliminates materials that are not used. In fish, this system leads from the mouth to the anus, an opening in front of the anal fin. Most fish have a jawed mouth with a tongue and teeth. A fish cannot move its tongue. Most fish have their teeth rooted in the jaws. They use their teeth to seize prey or to tear off pieces of their victim’s flesh. Some of them also have teeth on the roof of the mouth or on the tongue. Most fish also have teeth in the pharynx, a short tube behind the mouth. They use these teeth to crush or grind food.

In all fish, food passes through the pharynx on the way to the esophagus, another tubelike organ. A fish’s esophagus expands easily, which allows the fish to swallow its food whole. From the esophagus, food passes into the stomach, where it is partly digested. Some fish have their esophagus or stomach enlarged into a gizzard. The gizzard grinds food into small pieces before it passes into the intestines. The digestive process is completed in the intestines. The digested food enters the blood stream. Waste products and undigested food pass out through the anus.

Circulatory system

distributes blood to all parts of the body. It includes the heart and blood vessels. A fish’s heart consists of two main chambers—the atrium and the ventricle. The blood flows through veins to the atrium. It then passes to the ventricle. Muscles in the ventricle pump the blood through arteries to the gills, where the blood receives oxygen and gives off carbon dioxide. Arteries then carry the blood throughout the body. The blood carries food from the intestines and oxygen from the gills to the body cells. It also carries away waste products from the cells. A fish’s kidneys remove the waste products from the blood, which returns to the heart through the veins.

Nervous system

of fish, like that of other vertebrates, consists of a spinal cord, brain, and nerves. However, a fish’s nervous system is not so complex as that of mammals and other higher vertebrates. The spinal cord, which consists of soft nerve tissue, runs from the brain through the backbone. The brain is an enlargement of the spinal cord and is enclosed in the skull. The nerves extend from the brain and spinal cord to every part of the body. Some nerves, called sensory nerves, carry messages from the sense organs to the spinal cord and brain. Other nerves, called motor nerves, carry messages from the brain and spinal cord to the muscles. A fish can consciously control its skeletal muscles. But it has no conscious control over the smooth muscles and heart muscles. These muscles work automatically.

Reproductive system.

As in all vertebrates, the reproductive organs of fish are testes in males and ovaries in females. The testes produce male sex cells, or sperm. The sperm is contained in a fluid called milt. The ovaries produce female sex cells, or eggs. Fish eggs are also called roe or spawn. Most fish release their sex cells into the water through an opening near the anus. The males of some species have special structures for transferring sperm directly into the females. Male sharks, for example, have such a structure, called a clasper, on each pelvic fin. The claspers are used to insert sperm into the female’s body.

Special organs

Most bony fish have a swim bladder below the backbone. This baglike organ is also called a gas bladder. In most fish, the swim bladder provides buoyancy, which enables the fish to remain at a particular depth in the water. In lungfish and a few other fish, the swim bladder serves as an air-breathing lung. Still other fish, including many catfish, use their swim bladders to produce sounds as well as to provide buoyancy. Some species communicate by means of such sounds.

A fish would sink to the bottom if it did not have a way of keeping buoyant. Most fish gain buoyancy by inflating their swim bladder with gases produced by their blood. But water pressure increases with depth. As a fish swims deeper, the increased water pressure makes its swim bladder smaller and so reduces the fish’s buoyancy. The amount of gas in the bladder must be increased so that the bladder remains large enough to maintain buoyancy. A fish’s nervous system automatically regulates the amount of gas in the bladder so that it is kept properly filled. Sharks and rays do not have a swim bladder. To keep buoyant, most of these fish must swim constantly. When they rest, they stop swimming and so sink toward the bottom. Many bottom-dwelling bony fish also lack a swim bladder.

Many fish have organs that produce light or electricity. But these organs are simply adaptations of structures found in all or most fish. For example, many deep-sea fish have light-producing organs developed from parts of their skin or digestive tract. Some species use these organs to attract prey or possibly to communicate with others of their species. Various other fish have electricity-producing organs developed from muscles in their eyes, gills, or trunk. Some species use these organs to communicate or to stun or kill enemies or prey.

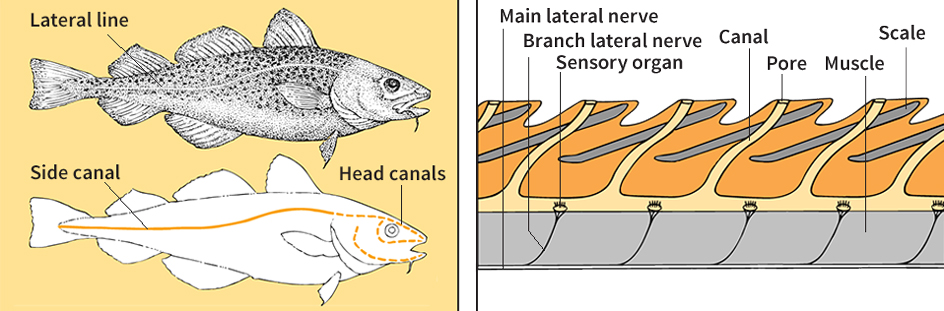

The senses of fish

Like all vertebrates, fish have sense organs that tell them what is happening in their environment. The organs enable them to see, hear, smell, taste, and touch. In addition, almost all fish have a special sense organ called the lateral line system, which enables them to “touch” objects at a distance. Fish also have various other senses that help them meet the conditions of life underwater.

Sight.

A fish’s eyes differ from those of land vertebrates in several ways. For example, most fish can see to the right and to the left at the same time. This ability makes up in part for the fact that a fish has no neck and so cannot turn its head. Fish also lack eyelids. In land vertebrates, eyelids help moisten the eyes and shield them from sunlight. A fish’s eyes are kept moist by the flow of water over them. They do not need to be shielded from sunlight because sunlight is seldom extremely bright underwater. Some fish have unusual adaptations of the eye. For example, adult flatfish have both eyes on the same side of the head. A flatfish spends most of the time lying on its side on the ocean floor and so needs eyes only on the side that faces upward. The eyes of certain deep-sea fish are on the ends of short structures that stick out from the head. These structures can be raised upward, allowing the fish to see overhead as well as to the sides and front.

A few kinds of fish are born blind. They include certain species of catfish that live in total darkness in the waters of caves and a species of whalefish, which lives in the ocean depths. Some of these fish have eyes but no vision. Others lack eyes completely.

Hearing.

All fish can probably hear sounds produced in the water. Fish can also hear sounds made on shore or above the water if they are loud enough. Catfish and certain other fish have a keen sense of hearing.

Fish have an inner ear enclosed in a chamber on each side of the head. Each ear consists of a group of pouches and tubelike canals. Fish have no outer ears or eardrums to receive sound vibrations. Sound vibrations are carried to the inner ears by the body tissues.

Smell and taste.

All fish have a sense of smell. It is highly developed in many species, including catfish, salmon, and sharks. In most fish, the olfactory organs (organs of smell) consist of two pouches, one on each side of the snout. The pouches are lined with nerve tissue that is highly sensitive to odors from substances in the water. A nostril at the front of each pouch allows water to enter the pouch and pass over the tissue. The water leaves the pouch through a nostril at the back.

Most fish have taste buds in various parts of the mouth. Some species also have them on other parts of the body. Catfish, sturgeon, and a number of other fish have fleshy whiskerlike growths called barbels near the mouth. They use the barbels both to taste and to touch.

Touch and the lateral line system

are closely related. Most fish have a well-developed sense of touch. Nerve endings throughout the skin react to the slightest pressure and change of temperature. The lateral line system senses changes in the movement of water. It consists mainly of a series of tiny canals under the skin. A main canal runs along each side of the trunk. Branches of these two canals extend onto the head. A fish senses the flow of water around it as a series of vibrations. The vibrations enter the lateral line through pores and activate certain sensitive areas in the line. If the flow of water around a fish changes, the pattern of vibrations sensed through the lateral line also changes. Nerves relay this information to the brain. Changes in the pattern of vibrations may warn a fish of approaching danger or indicate the location of objects outside its range of vision.

Other senses

include those that help a fish keep its balance and avoid unfavorable waters. The inner ears help a fish keep its balance. They contain a fluid and several hard, free-moving otoliths (ear stones). Whenever a fish begins to swim in other than an upright, level position, the fluid and otoliths move over sensitive nerve endings in the ears. The nerves signal the brain about the changes in the position of the body. The brain then sends messages to the fin muscles, which move to restore the fish’s balance. Fish can also sense any changes in the pressure, salt content, or temperature of the water and so avoid swimming very far into unfavorable waters.

How fish live

Every fish begins life in an egg. In the egg, the undeveloped fish, called an embryo, feeds on the yolk until ready to hatch. The section How fish reproduce discusses where and how fish lay their eggs. After a fish hatches, it is called a larva or fry. The fish reaches adulthood when it begins to produce sperm or eggs. Most small fish, such as guppies and many minnows, become adults within a few months after hatching. But some small fish become adults only a few minutes after hatching. Large fish require several years. Many of these fish pass through one or more juvenile stages before becoming adults. Almost all fish continue to grow as long as they live. During its lifetime, a fish may increase several thousand times in size. The longest-lived fish are probably certain sturgeon, some of which have lived in aquariums more than 50 years. For the life spans of various other fish in captivity, see Animal (table: Length of life of animals).

How fish get food.

Most fish are carnivores (meat-eaters). They eat shellfish, worms, and other kinds of water animals. Above all, they eat other fish. They sometimes eat their own young. Some fish are mainly herbivores (plant-eaters). They chiefly eat water plants and algae. Most of these fish probably also eat animals. Some fish live mainly on plankton. They include many kinds of flyingfish and herring and the three largest fish of all—the whale shark, giant manta ray, and basking shark. Some fish are scavengers. They feed mainly on waste products and on the dead bodies of animals that sink to the bottom.

Many fish have body organs specially adapted for capturing food. Certain fish of the ocean depths attract their prey with flashing lures. The dorsal fin of some anglerfish dangles above their mouth and serves as a bait for other fish. Such species as gars and swordfish have long, beaklike jaws, which they use for spearing or slashing their prey. Barracudas and certain piranhas and sharks are well known for their razor-sharp teeth, with which they tear the flesh from their victims. Electric eels and some other fish with electricity-producing organs stun their prey with an electric shock. Many fish have comblike gill rakers. These structures strain plankton from the water pumped through the gills.

How fish swim.

Most fish gain thrust (power for forward movement) by swinging the tail fin from side to side while curving the rest of the body alternately to the left and to the right. Some fish, such as marlin and tuna, depend mainly on tail motion for thrust. Other fish, including many kinds of eels, rely chiefly on the curving motion of the body. Fish maneuver by moving their fins. To make a left turn, for example, a fish extends its left pectoral fin. To stop, a fish extends both of its pectoral fins.

A fish’s swimming ability is affected by the shape and location of its fins. Most fast, powerful swimmers, such as swordfish and tuna, have a deeply forked or crescent-shaped tail fin and sickle-shaped pectorals. All their fins are relatively large. At the other extreme, most slow swimmers, such as bowfins and bullheads, have a squared or rounded tail fin and rounded pectorals.

Loading the player...Whitespotted filefish

How fish protect themselves.

All fish, except the largest ones, live in constant danger of being attacked and eaten by other fish or other animals. To survive, fish must be able to defend themselves against predators. If a species loses more individuals each generation than it gains, it will in time die out.

Protective coloration and protective resemblance are the most common methods of self-defense. A fish that blends with its surroundings is more likely to escape from its enemies than one whose color or shape is extremely noticeable. Many fish that do not blend with their surroundings depend on swimming speed or maneuvering ability to escape from their enemies.

Loading the player...School of snappers

Fish also have other kinds of defense. Some fish, such as gars, pipefish, and seahorses, are protected by a covering of thick, heavy scales or bony plates. Other species have sharp spines that are difficult for predators to swallow. In many of these species, including scorpionfish, sting rays, and stonefish, one or more of the spines can deliver a sting. When threatened, the porcupinefish inflates its spine-covered body with water until it is shaped like a balloon. The fish’s larger size and erect spines may discourage an enemy. Many eels that live on the bottom dig holes in which they hide from their enemies. Razor fish dive into sand on the bottom. A few fish do the opposite. For example, flyingfish and needlefish escape danger by propelling themselves out of the water.

How fish rest.

Like all animals, fish need rest. Many species have periods of what might be called sleep. Others simply remain inactive for short periods. But even at rest, many fish continue to move their fins to keep their position in the water.

Fish have no eyelids, and so they cannot close their eyes when sleeping. But while asleep, a fish is probably unaware of the impressions received by its eyes. Some fish sleep on the bottom, resting on their belly or side. Other species sleep in midwater, in a horizontal position. The slippery dick, a coral-reef fish, sleeps on the bottom under a covering of sand. The striped parrotfish, another coral-reef fish, encloses itself in an “envelope” of mucus before going to sleep. The fish secretes the mucus from special glands in its gill chambers.

Certain air-breathing fish, such as the African and South American lungfish, sleep out of water for months at a time. These fish live in rivers or ponds that dry up during periods of drought. The fish lie buried in hardened mud until the return of the rainy season. This kind of long sleep during dry periods is called estivation. During estivation, a fish breathes little and lives off the protein and fat stored in its body.

How fish live together.

Among many species, the individual fish that make up the species live mainly by themselves. Such fish include most predatory fish. Many sharks, for example, hunt and feed by themselves and join other sharks only for mating.

Loading the player...Filefish hover above a coral reef

Among many other species, the fish live together in closely knit groups called schools. About a fifth of all fish species are schooling species. A school may have few or many fish. A school of tuna, for example, may consist of fewer than 25 individuals. Many schools of herring number in the hundreds of millions. All the fish in a school are about the same size. Baby fish and adult fish are never in the same school. In some schooling species, the fish become part of a school when they are young and remain with it throughout their lives. Other species form schools for only a few weeks after they hatch. The fish in a school usually travel in close formation as a defense against predators. But a school often breaks up at night to feed and then regroups the next morning. The approach of a predator brings the fish quickly back together.

Fish also form other types of relationships. Among cod, perch, and many other species, a number of individuals may gather in the same area for feeding, resting, or spawning. Such a group is only temporary and is not so closely knit as a school. Some fish, including certain angelfish and wrasses, form unusual relationships with larger fish of other species. In many such relationships, the smaller fish removes parasites or dead tissue from the larger fish. The smaller fish thus obtains food, and the other is cleaned.

How fish adjust to change.

Fish sometimes need to adjust to changes in their environment. The two most common changes are (1) changes in water temperature and (2) changes in the salt content of water.

In general, the body temperature of each species of fish equals that of the water in which the species lives. If the water temperature rises or falls, a fish can adjust to the change because its body temperature changes accordingly. But the change in the water temperature must not be too great and must occur gradually. Most fish can adjust to a change in the water temperature of up to 15 °F (8 °C)—if the change is not sudden. Water temperatures usually change slowly, and so there is time for a fish’s body to make the necessary adjustment. But occasionally, the temperature drops suddenly and severely, killing many fish. In addition, freshwater fish are sometimes endangered by thermal pollution, which occurs when factories and electric power plants release hot water into rivers or lakes. The resulting increase in water temperature may be greater than most fish can adjust to.

Both fresh water and ocean water contain various salts, many of which fish need in their diet. But ocean water is far saltier than fresh water. Fish that migrate between the two must adjust to changes in the salt content of the water. Relatively few fish can make such an adjustment.

Both freshwater and saltwater fish have about the same amount of dissolved salts in their body fluids. But the body fluids of ocean fish are not so salty as the water in which the fish live. Under certain circumstances, water from a weak solution will flow into a strong solution. This natural process, called osmosis, takes place if the two solutions are separated by a membrane (thin layer) through which only the water can pass (see Osmosis). The skin and gill membranes of fish are of this type. For this reason, marine fish constantly lose water from their body fluids into the stronger salt solution of the sea water. To make up for this loss, they drink much water. But ocean water contains more salt than marine fish need. The fish pass the extra salt out through their gills and through their digestive tract. Saltwater fish need all the water they drink. As a result, these fish produce only small amounts of urine.

Freshwater fish have the opposite problem with osmosis. Their body fluids are saltier than fresh water. As a result, the fish constantly absorb water through their membranes. In fact, freshwater fish absorb so much water that they do not need to drink any. Instead, the fish must get rid of the extra water that their bodies absorb. As a result, freshwater fish produce great quantities of urine.

How fish reproduce

All fish reproduce sexually. In sexual reproduction, a sperm unites with an egg in a process called fertilization. The fertilized egg develops into a new individual. Males produce sperm and females produce eggs in almost all fish species. But in a few species, the same individual produces both sperm and eggs. In many species, fish change sex during their lifetime. Fish born as males may later become females, and fish born as females may later become males.

The eggs of most fish are fertilized outside the female’s body. A female releases her eggs into the water at the same time that a male releases his sperm. Some sperm come in contact with some of the eggs, and fertilization takes place. This process is called external fertilization. The entire process during which eggs and sperm are released into the water and the eggs are fertilized is called spawning. Almost all bony fish reproduce in this way.

Sharks, rays, chimaeras, and a few bony fish, such as guppies and mosquito fish, reproduce in a different manner. The eggs of these fish are fertilized inside the female, a process called internal fertilization. For internal fertilization to occur, males and females must mate. The males have special organs for transferring sperm into the females. After fertilization, the females of some species release their eggs into the water before they hatch. Other females hatch the eggs inside their bodies and so give birth to living young. Fish that bear living young include many sharks and rays, guppies, and some halfbeaks and scorpionfish.

This section discusses spawning, the method by which most fish reproduce.

Preparation for spawning.

Most fish have a spawning season each year, during which they may spawn several times. But some tropical species breed throughout the year. The majority of fish spawn in spring or early summer, when the water is warm and the days are long. But certain cold-water fish, such as brook trout and Atlantic cod, spawn in fall or winter.

Most fish return to particular spawning grounds year after year. Many freshwater fish have to travel only a short distance to their spawning grounds. They may simply move from the deeper parts of a river or lake to shallow waters near shore. But other fish may migrate tremendous distances to spawn. For example, European freshwater eels cross 3,000 miles (4,800 kilometers) of ocean to reach their spawning grounds in the western Atlantic.

At their spawning grounds, the males and females of some species swim off in pairs to spawn. Among other species, the males and females spawn in groups. Many males and females tell each other apart by differences in appearance. The females of some species are larger than the males. Among other species, the males develop unusually bright colors during the spawning season. During the rest of the year, they look much like the females of their species. In some species, the males and females look so different that for many years scientists thought they belonged to different species. Among other fish, the sexes look so much alike that they can be told apart only by differences in their behavior. For example, many males adopt a special type of courting behavior to attract females. A courting male may swim round and round a female or perform a lively “dance” to attract her attention.

Among some species, including cod, fightingfish, and certain gobies and sticklebacks, a male claims a territory for spawning and fights off any male intruders. Many fish, especially those that live in fresh water, build nests for their eggs. A male freshwater bass, for example, uses its tail fin to scoop out a nest on the bottom of a lake or stream.

Spawning and care of the eggs.

After the preparations have been made, the males and females touch in a certain way or make certain signals with their fins or body. Depending on the species, a female may lay a few eggs or many eggs—even millions—during the spawning season. Most fish eggs measure 1/8 inch (3 millimeters) in diameter or less.

Some fish, such as cod and herring, abandon their eggs after spawning. A female cod may lay as many as 9 million eggs during a spawning season. Cod eggs, like those of many other ocean fish, float near the surface and scatter as soon as they are laid. Predators eat many of the eggs. Others drift into waters too cold for hatching. Only a few cod eggs out of millions develop into adult fish. A female herring lays about 50,000 eggs in a season. But herring eggs, like those of certain other marine fish, sink to the bottom and have an adhesive covering that helps them stick there. As a result, herring eggs are less likely to be eaten by predators or to drift into waters unfavorable for hatching.

A number of fish protect their eggs. They include many freshwater nest builders, such as bass, salmon, certain sticklebacks, and trouts. The females of these species lay far fewer eggs than do the females of the cod and herring groups. Like herring eggs, the eggs of many of the freshwater nest builders sink to the bottom and have an adhesive covering. But they have an even better chance of surviving than herring eggs because they receive some protection.

The amount and kind of protection given by fish to their eggs vary greatly. Salmon and trout cover their fertilized eggs with gravel but abandon them soon after. Male freshwater bass guard the eggs fiercely until they hatch. Among ocean fish, female seahorses and pipefish lay their eggs in a pouch on the underside of the male. The eggs hatch inside the male’s pouch. Some fish, including certain ocean catfish and cardinal fish, carry their eggs in their mouth during the hatching period. In some species, the male carries the eggs. In other species, the female carries them.

Hatching and care of the young.

The eggs of most fish species hatch in less than two months. Eggs laid in warm water hatch faster than those laid in cold water. The eggs of some tropical fish hatch in less than 24 hours. On the other hand, the eggs of certain cold-water fish require four or five months to hatch. The males of a few species guard their young for a short time after they hatch. These fish include freshwater bass, bowfins, brown bullheads, Siamese fightingfish, and some sticklebacks. But most other fish provide no protection for their offspring.

The development of fish

Scientists learn how fish evolved by studying the fossils of fish that are now extinct. The fossils show the changes that occurred in the anatomy of fish down through the ages.

The first fish

appeared on Earth about 500 million years ago. These fish are called ostracoderms. They were slow, bottom-dwelling animals that were covered from head to tail with a heavy armor of thick bony plates and scales. Like today’s lampreys and hagfish, ostracoderms had no jaws and had poorly formed fins. For this reason, scientists group lampreys, hagfish, and ostracoderms together. Ostracoderms were not only the first fish, but they were also the first animals to have a backbone. Most scientists believe that the history of all other vertebrates can be traced back to the ostracoderms. The ostracoderms gave rise to jawed fish with backbones, and they in turn gave rise to tetrapods (vertebrates with four legs). These tetrapods spent part of their lives on land. Some tetrapods became the ancestors of all land vertebrates.

Ostracoderms probably reached the peak of their development about 400 million years ago. About the same time, two other groups of fish were developing—acanthodians and placoderms. The acanthodians became the first known jawed fish. The placoderms were the largest fish up to that time. Some members of the placoderm group called Dunkleosteus grew up to 23 feet (7 meters) long and had powerful jaws and sharp bony plates that served as teeth.

The Age of Fishes

was a period in Earth’s history when fish developed remarkably. Scientists call this age the Devonian Period. It began about 420 million years ago and lasted about 60 million years. During much of this time, Dunkleosteus and other large placoderms ruled the seas.

The first bony fish appeared early in the Devonian Period. They were mostly small or medium-sized and, like all fish of that time, were heavily armored. These early bony fish belonged to two main groups—sarcopterygians and actinopterygians.

The sarcopterygians had fleshy or lobed fins. Few fish today are even distantly related to this group. The coelacanth and the lungfish are the only surviving sarcopterygians. However, it was the sarcopterygians that gave rise to tetrapods. Thus, all amphibians, birds, mammals, and reptiles descended from sarcopterygian fish. The actinopterygians had rayed fins without fleshy lobes at the base. Among the first actinopterygians were the chondrosteans, which differed in many ways from modern ray-finned fish. The chondrosteans were the ancestors of today’s ray-finned fish, which make up about 95 percent of all the world’s fish species. The paddlefish and sturgeons are the only surviving chondrosteans, and most scientists believe the bichirs are their nearest relatives.

The first sharks appeared during the Devonian Period. They looked much like certain sharks that exist today. The first rays appeared about 200 million years after the first sharks. By the end of the Devonian Period, nearly all jawless fish had become extinct. The only exceptions were the ancestors of today’s lampreys and hagfish. Some acanthodians and placoderms remained through the Devonian Period, but these fish also died out in time.

The first modern fish

appeared during the Mesozoic Era, which began about 250 million years ago. The chondrosteans of the Devonian Period had given rise to the first neopterygians, the group from which most of today’s fish species developed. Modern bowfin and freshwater gars resemble the earliest forms of neopterygians. From fish such as these arose the teleosts, the advanced modern fishes.

The teleosts lost the heavy armor that covered the bodies of most earlier fish. At first, all teleosts had soft-rayed fins. These fish gave rise to present-day catfish, eels, minnows, and other soft-finned fish. The first spiny-finned fish appeared during the Cretaceous Period, which began about 145 million years ago. These fish were the ancestors of such highly developed present-day fish as perch and tuna. Since the Cretaceous Period, teleosts have been by far the most important group of fish.

A classification of fish

Ichthyologists classify fish into various groups according to the body characteristics they have in common. They divide all fish into two superclasses: (1) Agnatha, meaning jawless, and (2) Gnathostomata, meaning jawed. The superclass Agnatha consists of two classes of living species that are grouped into two orders. The much larger superclass Gnathostomata is divided into classes, subclasses, and orders. The orders are further divided into families, the families into genera, and the genera into species.

The table with this article lists the major groups down through orders into which fish are classified. The groups are arranged according to their probable evolutionary development. One or more representative families are listed after the name of each order, along with important characteristics of the fish in the order. The table lists 42 orders. But some ichthyologists list fewer than 42, and others list more. Ichthyologists also disagree on the names of some orders, the way the orders should be arranged, and the species included in each.