Forest is a large area of land covered with trees. But a forest is much more than just trees. It also includes smaller plants, such as mosses, shrubs, and wildflowers. In addition, many kinds of birds, insects, and other animals make their home in the forest. Millions upon millions of living things that can only be seen under a microscope also live in the forest.

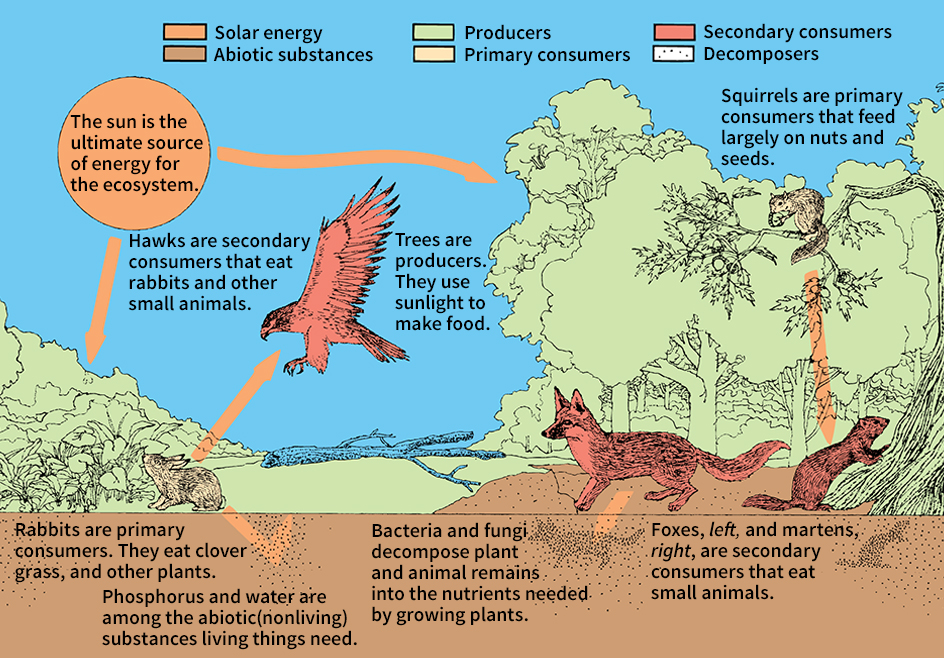

Climate, soil, and water determine the kinds of plants and animals that can live in a forest. The living things and their environment together make up the forest ecosystem. An ecosystem consists of all the living and nonliving things in a particular area and the relationships among them.

The forest ecosystem is highly complicated. The trees and other green plants use sunlight to make their own food from the air and from water and minerals in the soil. The plants themselves serve as food for certain animals. These animals, in turn, are eaten by other animals. After plants and animals die, their remains are broken down by bacteria and other organisms, such as protozoans and fungi. This process returns minerals to the soil, where they can again be used by plants to make food.

Although individual members of the ecosystem die, the forest itself lives on. If the forest is wisely managed, it provides us with a continuous source of wood and many other products.

Before people began to clear the forests for farms and cities, great stretches of forestland covered about 60 percent of Earth’s land area. Today, forests occupy about 30 percent of the land. The forests differ greatly from one part of the world to another. For example, the steamy, vine-choked rain forests of central Africa are far different from the cool, towering spruce and fir forests of northern Canada.

For detailed information on forest products and forest management, see the articles Forest products and Forestry.

The importance of forests

Forests have always had great importance to people. Prehistoric people got their food mainly by hunting and by gathering wild plants. Many of these people lived in the forest and were a natural part of it. With the development of civilization, people settled in cities. But they still went to the forest to get timber and to hunt.

Today, people depend on forests more than ever, especially for their (1) economic value, (2) environmental value, and (3) enjoyment value. The science of forestry is concerned with increasing and preserving these values by careful management of forestland.

Economic value.

Forests supply many products. Wood from forest trees provides lumber, plywood, railroad ties, and shingles. It is also used in making furniture, tool handles, and thousands of other products. In many parts of the world, wood serves as the chief fuel for cooking and heating.

Various manufacturing processes change wood into a great number of different products. Paper is one of the most valuable products made from wood. Other processed wood products include cellophane, plastics, and such fibers as rayon and acetate.

Forests provide many important products besides wood. Latex, which is used in making rubber, and turpentine come from forest trees. Various fats, gums, oils, and waxes used in manufacturing also come from trees. In some primitive societies, forest plants and animals make up a large part of the people’s diet.

Unlike most other natural resources, such as coal, oil, and mineral deposits, forest resources are renewable. As long as there are forests, people can count on a steady supply of forest products.

Environmental value.

Forests help conserve and enrich the environment in several ways. For example, forest soil soaks up large amounts of rainfall. It thus prevents the rapid runoff of water that can cause erosion and flooding. In addition, rain is filtered as it passes through the soil and becomes ground water. This ground water flows through the ground and provides a clean, fresh source of water for streams, lakes, and wells.

Forest plants, like all green plants, help renew the atmosphere. As the trees and other green plants make food, they give off oxygen. They also remove carbon dioxide from the air. People and nearly all other living things require oxygen. If green plants did not continuously renew the oxygen supply, almost all life would soon stop. If carbon dioxide increases in the atmosphere, it could severely alter Earth’s climate.

Forests also provide a home for many plants and animals that can live nowhere else. Without the forest, many kinds of wildlife could not exist.

Enjoyment value.

The natural beauty and peace of the forest offer a special source of enjoyment. In the United States, Canada, and many other countries, huge forestlands have been set aside for people’s enjoyment. Many people use these forests for such activities as camping, hiking, and hunting. Others visit them simply to enjoy the scenery and relax in the quiet beauty.

The structure of forests

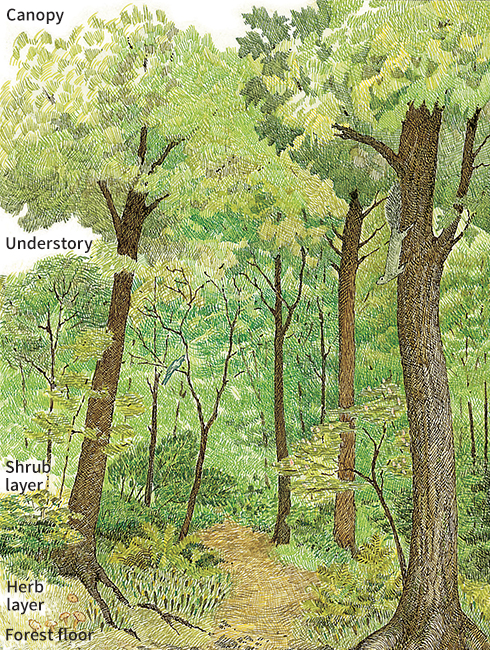

Every forest has various strata (layers) of plants. The five basic forest strata, from highest to lowest, are (1) the canopy, (2) the understory, (3) the shrub layer, (4) the herb layer, and (5) the forest floor.

The canopy

consists mainly of the crowns (branches and leaves) of the tallest trees. The most common trees in the canopy are called the dominant trees of the forest. Certain plants, especially climbing vines and epiphytes, may grow in the canopy. Epiphytes are plants that grow on other plants for support but absorb from the air the water and other materials they need to make food.

The canopy receives full sunlight. As a result, it produces more food than does any other layer. In some forests, the canopy is so dense it almost forms a roof over the forest. Fruit-eating birds, and insects and mammals that eat leaves or fruit, live in the canopy.

The understory

is made up of trees shorter than those of the canopy. Some of these trees are smaller species that grow well in the shade of the canopy. Others are young trees that may in time join the canopy layer. Because the understory grows in shade, it is not as productive as the canopy. However, the understory provides food and shelter for many forest animals.

The shrub layer

consists mainly of shrubs. Shrubs, like trees, have woody stems. But unlike trees, they have more than one stem, and none of the stems grows as tall as a tree. Forests with a dense canopy and understory may have only a spotty shrub layer. The trees in such forests filter out so much light that few shrubs can grow beneath them. Most forests with a more open canopy and understory have heavy shrub growth. Many birds and insects live in the shrub layer.

The herb layer

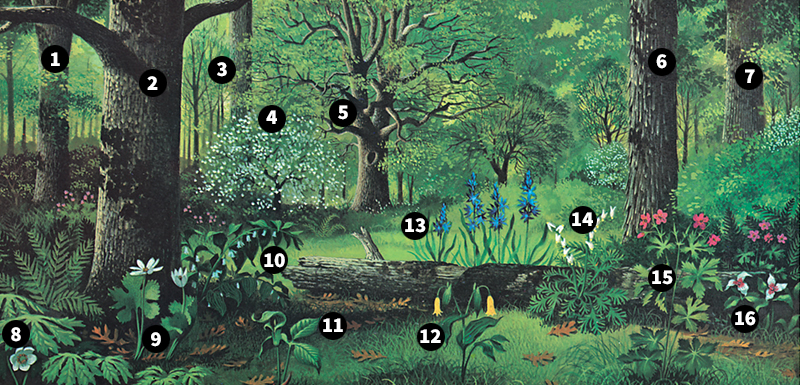

consists of ferns, grasses, wildflowers, and other soft-stemmed plants. Tree seedlings also make up part of this layer. Like the shrub layer, the herb layer grows thickest in forests with a more open canopy and understory. Yet even in forests with dense tree layers, enough sunlight reaches the ground to support some herb growth. The herb layer is the home of forest animals that live on the ground. They include such small animals as insects, mice, snakes, turtles, and ground-nesting birds and such large animals as bears and deer.

The forest floor

is covered with mats of moss and with various objects that have fallen from the upper layers. Leaves, twigs, and animal droppings—as well as dead animals and plants—build up on the forest floor. Among these objects, an incredible number of small organisms can be found. They include earthworms, fungi, insects, and spiders, plus countless bacteria and other microscopic life. All these organisms break down the waste materials into the basic chemical elements necessary for new plant growth.

Kinds of forests

Many systems are used to classify the world’s forests. Some systems classify a forest according to the characteristics of its dominant trees. A needleleaf forest, for example, consists of a forest in which the dominant trees have long, narrow, needlelike leaves. Such forests are also called coniferous (cone-bearing) because the trees bear cones. The seeds grow in these cones. A broadleaf forest is made up mainly of trees with broad, flat leaves. Forests in which the dominant trees shed all their leaves during certain seasons of the year, and then grow new ones, are classed as deciduous forests. In an evergreen forest, the dominant trees grow new leaves before shedding the old ones. Thus, they remain green throughout the year.

In some other systems, forests are classified according to the usable qualities of the trees. A forest of broadleaf trees may be classed as a hardwood forest because most broadleaf trees have hard wood, which makes fine furniture. A forest of needleleaf trees may be classed as a softwood forest because most needleleaf trees have softer wood than broadleaf trees have.

Many scientists classify forests according to various ecological systems. Under such systems, forests with similar climate, soil, and amounts of moisture are grouped into formations. Climate, soil, and moisture determine the kinds of trees found in a forest formation. One common ecological system groups the world’s forests into six major formations. They are (1) tropical rain forests, (2) tropical dry forests, (3) temperate deciduous forests, (4) temperate evergreen forests, (5) boreal forests, and (6) savannas.

Tropical rain forests

grow near the equator, where the climate is warm and wet the year around. The largest of these forests grow in the Amazon River Basin of South America, the Congo River Basin of Africa, and throughout much of Southeast Asia.

Of the six forest formations, tropical rain forests have the greatest variety of trees. As many as 100 species—none of which is dominant—may grow in 1 square mile (2.6 square kilometers) of land. Nearly all the trees of tropical rain forests are broadleaf evergreens, though some palm trees and tree ferns can also be found. In most of the forests, the trees form three canopies. The upper canopy may reach more than 165 feet (50 meters) high. A few exceptionally tall trees, called emergents, tower above the upper canopy. The understory trees form the two lower canopies.

The shrub and herb layers are sparse because little sunlight penetrates the dense canopies. However, many climbing plants and epiphytes crowd the branches of the canopies, where the sunlight is fullest.

Most of the animals of the tropical rain forests also live in the canopies, where they can find plentiful food. These animals include such flying or climbing creatures as bats, birds, insects, lizards, mice, monkeys, opossums, sloths, and snakes.

Tropical dry forests

grow in warm areas that have wet and dry seasons. Such conditions occur in tropical to subtropical regions in many parts of the world. Tropical dry forests also are known as tropical seasonal forests or seasonally dry tropical forests.

Tropical dry forests have a great variety of tree species, though not nearly as many as the rain forests. They also have fewer climbing plants and epiphytes. Unlike the trees of the rain forest, many tropical dry species are deciduous. The deciduous trees are found in regions with especially distinct wet and dry seasons. The trees shed their leaves in the dry season.

Tropical dry forests have a canopy about 100 feet (30 meters) high. One understory grows beneath the canopy. Bamboos and palms may form a dense shrub layer, and a thick herb layer blankets the ground. The animal life resembles that of the rain forest.

Temperate deciduous forests

grow in eastern North America, western Europe, and eastern Asia. These regions have a temperate climate, with warm summers and cold winters.

The canopy of temperate deciduous forests is about 100 feet (30 meters) high. Two or more kinds of trees dominate the canopy, and another 15 to 25 kinds may be present. Most of the trees in these forests are broadleaf and deciduous. They shed their leaves in fall. The understory, shrub, and herb layers may be dense. The herb layer has two growing periods each year. Plants of the first growth appear in early spring, before the trees have developed new leaves. These plants die by summer and are replaced by plants that grow in the shade of the leafy canopy.

Large animals of the temperate deciduous forests include bears, deer, and, rarely, wolves. These forests are also the home of hundreds of smaller mammals and birds. Many of the birds migrate south in fall, and some of the mammals hibernate during the winter.

Some temperate areas support mixed deciduous and evergreen forests. In the Great Lakes region of North America, for example, the cold winters promote the growth of heavily mixed forests of deciduous and evergreen trees. Forests of evergreen pine and deciduous oak and hickory grow on the dry coastal plains of the Southeastern United States.

Temperate evergreen forests.

In some temperate regions, the environment favors the growth of evergreen forests. Such forests grow along coastal areas that have mild winters with heavy rainfall. These areas include the northwest coast of North America, the south coast of Chile, the west coast of New Zealand, and the southeast coast of Australia. Temperate evergreen forests also cover the lower mountain slopes in Asia, Europe, and western North America. In these regions, the cool climate favors the growth of evergreen trees.

The strata and the plant and animal life vary greatly from one temperate evergreen forest to another. For example, the mountainous evergreen forests of Asia, Europe, and North America are made up of conifers. The coastal forests of Australia and New Zealand, on the other hand, consist of broadleaf evergreen trees.

Boreal forests,

also called taiga, are found in regions that have an extremely cold winter and a short growing season. The word boreal means northern. Vast boreal forests stretch across northern Europe, Asia, and North America. Similar forests also cover the higher mountain slopes on these continents.

Boreal forests have the simplest structure of all forest formations. They have only one uneven layer of trees, which reaches up to about 75 feet (23 meters) high. In most of the boreal forests, the dominant trees are needleleaf evergreens—either spruce and fir or spruce and pine. The shrub layer is spotty. However, mosses and lichens form a thick layer on the forest floor and also grow on the tree trunks and branches. There are few herbs.

Many small mammals, such as beavers, mice, porcupines, and snowshoe hares, live in the boreal forests. Larger mammals include bears, caribou, foxes, moose, and wolves. Birds of the boreal forests include ducks, loons, owls, warblers, and woodpeckers.

Savannas

are areas of widely spaced trees. In some savannas, the trees grow in clumps. In others, individual trees grow throughout the area, forming an uneven, widely open canopy. In either case, most of the ground is covered by shrubs and herbs, especially grasses. As a result, some biologists classify savannas as grasslands. Savannas are found in regions where low rainfall, poor soil, frequent fires, or other environmental features limit tree growth.

The largest savannas are tropical savannas. They grow throughout much of Central America, Brazil, Africa, India, Southeast Asia, and Australia. Animals of the tropical savannas include giraffes, lions, tigers, and zebras.

Temperate savannas, also called woodlands, grow in the United States, Canada, Mexico, and Cuba. They have such animals as bears, deer, elk, and pumas.

Forests of the United States and Canada

The United States and Canada are rich in forests. Before the first white settlers arrived in the 1600’s, forests covered most of the land from the Atlantic Ocean to the Mississippi River. Altogether, nearly 40 percent of the land north of Mexico was forested at that time. More than half this forestland was in Canada and Alaska, where only a small portion has been cleared. Even in the lower United States, forests still grow on much of the original forestland. Today, the United States has about 755 million acres (305 million hectares) of forests. Canada has about 865 million acres (350 million hectares). In both countries, forests cover about a third of the land area.

The forests of the United States and Canada include all the major formations discussed in the previous section, except for tropical rain forests. The U.S.-Canadian forests can be divided into many smaller formations. One common system recognizes nine U.S.-Canadian formations. They are (1) subtropical forests, (2) southern deciduous-evergreen forests, (3) deciduous forests, (4) northern deciduous-evergreen forests, (5) temperate savannas, (6) mountain evergreen forests, (7) Pacific coastal forests, (8) boreal forests, and (9) subarctic woodlands.

Subtropical forests

thrive along the coasts of the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico in the Southeastern United States. In these regions, the climate stays hot and humid throughout the year.

In southern Florida, raised areas of the swampy Everglades support forests of live oak, mahogany, and sabal palmetto. These forests have a dense undergrowth of ferns, shrubs, and small trees. Epiphytes and vines crowd the branches of the taller trees. Broadleaf-evergreen forests grow farther north, along the edges of the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. The dominant trees in these forests are bay, holly, live oak, and magnolia. Thick growths of Spanish moss, an epiphyte that looks like long gray hair, hang from the branches.

Southern deciduous-evergreen forests

grow on the flat, sandy coastal plains of the Southeastern United States. The forests extend along the Atlantic Coastal Plain from New Jersey to Florida and along the Gulf Coastal Plain from Florida to Texas. These regions have long, hot summers and short winters.

Most of the forests consist of evergreen pine and deciduous oak. Pitch pine is the most common evergreen in the northern part of these forests. Going southward, pitch pine is replaced, in order, by loblolly, longleaf, and slash pine.

Deciduous forests

occupy a region bounded by the coastal plains on the south and east, the Great Lakes on the north, and the Great Plains on the west. This region has dependable rainfall and distinct seasons. Severe frosts and heavy snows occur during winter in the northern parts of this formation.

The northern part of the deciduous forest region was once covered by glaciers. But the glaciers did not reach the southern portion, which has the oldest and richest deciduous forest in North America. This forest lies in the central Appalachian Mountains region. The dominant trees of the forest include ash, basswood, beech, buckeye, cucumber magnolia, hickory, sugar maple, yellow-poplar, and several kinds of oaks.

In most deciduous forests outside the central Appalachians, fewer species of trees dominate. For example, various kinds of oaks dominate the forests from southern New England to northwestern Georgia. Hickory and yellow-poplars—and in drier areas several species of pine—grow among the oak trees. Beech and sugar maple trees dominate the northeastern and north-central deciduous forests. However, these forests also have many other kinds of trees, such as black cherry, red maple, red oak, and white elm. The northwestern deciduous forests are dominated by basswood and maple. Some oak trees also grow in these forests.

Northern deciduous-evergreen forests

stretch from the Great Lakes across southeastern Canada and northern New York and New England. In this region of cold winters and warm summers, deciduous trees of the south are mixed with conifers of the north.

The dominant evergreens throughout much of this region include white-cedar, hemlock, and jack, red, and white pine. The chief broadleaf species include basswood, beech, sugar maple, white ash, and yellow birch. In moist areas, hemlock and white-cedar grow in mixed stands with black ash and white elm. Drier areas have forests of red and white pine, which is mixed with some ironwood and red oak. Areas that are neither especially dry nor moist support maple or beech forests. The region’s swamps are covered with black spruce and larch.

Temperate savannas

are found in areas of Canada and the United States that have lower annual rainfall and a long season of dryness. Temperate savannas dominated by aspen grow in North Dakota, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta. Outside this region, oak, pine, or both oak and pine dominate the temperate savannas of North America. Savannas of bur oak, mixed in some areas with other oaks or hickory, extend in a belt from Manitoba through Texas. Coniferous savannas of juniper and pinon pine cover the dry foothills of the mountainous regions of the Southwestern United States from Texas to Arizona, and the southern half of Mexico. In California, the foothills of the Sierra Nevada have similar savannas of blue oak and digger pine. Along the coast of southern California, the climate supports a broadleaf savanna of various species of oaks.

Mountain evergreen forests

grow above the foothill savannas of the mountains of the western United States and Canada. In general, the climate in the mountains becomes colder, wetter, and windier with increasing altitude. The forests of the lower and middle slopes are called montane forests. Those of the upper slopes are known as subalpine forests.

In the Rockies, the lower montane forests consist of unmixed stands of ponderosa pine. At higher elevations, Douglas-fir becomes dominant. Douglas-fir is mixed with grand fir in the northern Rockies and with blue spruce and white fir in the southern Rockies. Above this zone lie the cold, snowy subalpine forests, which are dominated by Engelmann spruce and subalpine fir. Lodgepole pine is also common in both the montane and subalpine zones, especially in areas that have been affected by fire. The highest elevation at which trees can grow is called the timber line. Beyond this point, the climate is too severe for tree growth. At the timber line, the trees grow in a scattered, savannalike way. The timber-line regions are dominated by bristlecone pine in the southern Rockies, by limber pine in the central Rockies, and by Lyall’s larch and whitebark pine in the northern Rockies.

In the Sierra Nevada, incense-cedar grows in moist areas of the lower montane forests. Douglas-fir, Jeffrey pine, ponderosa pine, and sugar pine thrive on drier slopes. In central California, magnificent giant sequoia trees grow on the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada. Sequoias are the bulkiest, though not the tallest, of all trees. The largest sequoias measure about 100 feet (30 meters) around at the base. White fir dominates the upper montane forests of the Sierra Nevada. At subalpine elevations, mountains support forests of red fir mixed with lodgepole pine and mountain hemlock. These subalpine forests thin out into savannas of bristlecone and whitebark pine at elevations near the timber line.

Pacific coastal forests

extend along the Pacific Ocean from west-central California to Alaska. The warm currents of the Pacific help give this region a mild climate the year around. Warm, moisture-filled winds from the ocean bring heavy annual precipitation.

Huge conifers dominate the Pacific coastal forests. Forests of redwood, the tallest living trees, grow along a narrow coastal strip from central California to southern Oregon. Many of these giants tower more than 300 feet (91 meters). Inland from the redwoods and to the north grow magnificent forests of Douglas-fir, Sitka spruce, western hemlock, and western redcedar. Along the coast of northern Washington and southern British Columbia, high annual precipitation supports thick temperate rain forests. These forests, with their moss-covered Douglas-fir, western hemlock, Sitka spruce, and western redcedar, make up a damp, green wilderness found nowhere else in North America.

Boreal forests

sweep across northern North America from northwestern Alaska to the island of Newfoundland. In this region of severe cold and heavy snowfall, winter lasts seven to eight months. However, the short growing season has dependable rainfall and many hours of daylight. Boreal forests are dominated by coniferous evergreens, chiefly balsam fir, black spruce, jack pine, and white spruce. Some areas support larch, a deciduous conifer. Such deciduous broadleaf trees as balsam poplar, quaking aspen, and white birch grow in areas that have been burned over by forest fires. Boreal forests have many bogs (areas of wet, spongy ground). Some bogs are treeless. Other bogs, called muskegs, are covered by a deep mat of moss on which dwarfed conifers grow.

Subarctic woodlands

lie along the northern edge of the boreal forests. The climate in this region is bitterly cold, with low precipitation and an extremely brief growing season. These conditions force the trees to grow in a widely spaced, savannalike fashion. Black spruce dominates most of the region. Other boreal trees, such as aspen, larch, white birch, and white spruce, grow in some places. North of the woodlands lies the Arctic tundra, where trees cannot survive.

The life of the forest

Forests are filled with an incredible variety of plant and animal life. For example, scientists recorded nearly 10,500 kinds of organisms in a deciduous forest in Switzerland. The number of individual plants and animals in a forest is enormous.

All life in the forest is part of a complex ecosystem, which also includes the physical environment. Ecologists study forest life by examining the ways in which the organisms interact with one another and their environment. Such interactions involve (1) the flow of energy through the ecosystem, (2) the cycling of essential chemicals within the ecosystem, and (3) competition and cooperation among the organisms.

Loading the player...Animals of tropical forests

The flow of energy.

All organisms need energy to stay alive. In forests, as in most other ecosystems, life depends on energy from the sun. However, only the green plants in the forest can use the sun’s energy directly. Through a process called photosynthesis, they use sunlight to produce food.

All other forest organisms rely on green plants to capture the energy of sunlight. Green plants are thus the primary producers in the forest. Animals that eat plants are known as primary consumers or herbivores. Animals that eat herbivores are called secondary consumers or predators. Secondary consumers themselves may fall prey to other predators, called tertiary (third) consumers. This series of primary producers and various levels of consumers is known as a food chain.

In a typical forest food chain, tree leaves (primary producers) are eaten by caterpillars (primary consumers). The caterpillars, in turn, are eaten by shrews (secondary consumers), which are then eaten by owls (tertiary consumers). Energy, in the form of food, passes from one level of the food chain to the next. But much energy is lost at each level. Therefore, a forest ecosystem can support, in terms of weight, far more green plants than herbivores and far more herbivores than predators.

The cycling of chemicals.

All living things are made up of certain basic chemical elements. The supply of these chemicals is limited, and so they must be recycled for life to continue.

The decomposers of the forest floor promote chemical recycling. Decomposers include bacteria, earthworms, fungi, and some insects. They obtain food by breaking down dead plants and the wastes and dead bodies of animals into their basic chemicals. The elements pass into the soil, where they are absorbed by the roots of growing plants. Without decomposition, the supply of such essential elements as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium would soon be exhausted.

Some chemical recycling does not involve decomposers. Green plants, for example, release oxygen during photosynthesis. Animals—and plants as well—need this chemical to oxidize (burn) food and so release energy. In the oxidation process, animals and plants give off carbon dioxide, which the green plants need for photosynthesis. Thus the cycling of oxygen and carbon dioxide works together and maintains a steady supply of the two chemicals.

Competition and cooperation.

Every forest animal and plant must compete with individuals of its own and similar species for such necessities as nutrients, space, and water. For example, red squirrels in a boreal forest must compete with one another—and with certain other herbivores—for conifer seeds, their chief food. Similarly, the conifers compete with one another and with other types of plants for water and sunlight. This competition helps ensure that the organisms best adapted to the forest will survive and reproduce.

Cooperation among the organisms of the forest is common. For many species, cooperation is necessary for survival. For example, birds and mammals that eat fruit rely on plants for food. But the plants, in turn, may depend on these animals to help spread their seeds. Similarly, certain microscopic fungi grow on roots of trees. The fungi obtain food from the tree, but they also help the tree absorb needed water and nutrients.

For a diagram of a forest ecosystem, see Ecology.

Forest succession

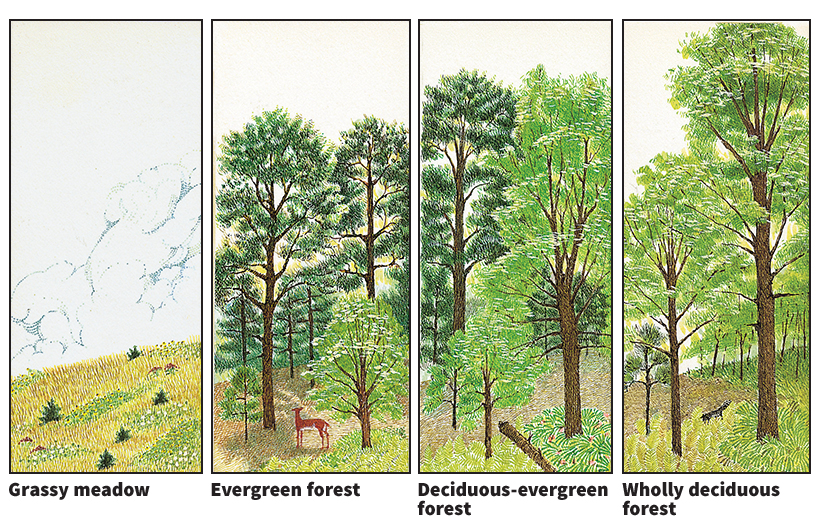

In forests and other natural areas, a series of orderly changes may occur in the kinds of plants and animals that live in the area. This series of changes is called ecological succession. Areas undergoing succession pass through one or more intermediate stages until a final climax stage is reached. Forests exist in intermediate or climax stages of ecological succession in a great number of places.

To illustrate how a forest develops and succession occurs, let us imagine an area of abandoned farmland in the Southeastern United States. The abandoned land will first support communities of low-growing weeds, insects, and mice. The land then gradually becomes a meadow as grasses and larger herbs and shrubs begin to appear. At the same time, rabbits, snakes, and ground-nesting birds begin to move into the area.

In a few years, young pine trees stand throughout the meadow. As the trees mature, the meadow becomes an intermediate forest of pines. The meadow herbs and shrubs die and are replaced by plants that grow better in the shade of the pine canopy. As the meadow plants disappear, so do the food chains based on them. New herbivores and predators enter the area, forming food chains based on the plant life of the pine forest.

Years pass, and the pines grow old and large. But few young pines grow beneath them because pine seedlings need direct sunlight. Instead, broadleaf trees—particularly oaks—form the understory. As the old pines die, oaks fill the openings in the canopy. Gradually, a mixed deciduous-evergreen forest develops.

But the succession is still not complete. Young oaks grow well in the shade of the canopy, but pines do not. Therefore, a climax oak forest may eventually replace the mixed forest. However, pine wood is more valuable than oak wood. For this reason, foresters in the Southeastern United States use controlled fires to check the growth of oaks and so prevent climax forests from developing.

Different successional series occur in different areas. In southern boreal regions, for instance, balsam fir and white spruce dominate the climax forests. If fire, disease, or windstorms destroy a coniferous forest, an intermediate forest of quaking aspen and white birch may develop in its place. These deciduous trees grow better in direct sunlight and on unprotected, bare ground than do fir and spruce.

The aspen-birch forest provides the protection young boreal conifers need, and soon spruce and fir seedlings make up most of the understory. In time, these conifers grow taller than the aspen and birch trees. Deciduous species cannot reproduce in the shade of the new canopy, and eventually the climax forest of fir and spruce trees is reestablished.

The history of forests

The first forests

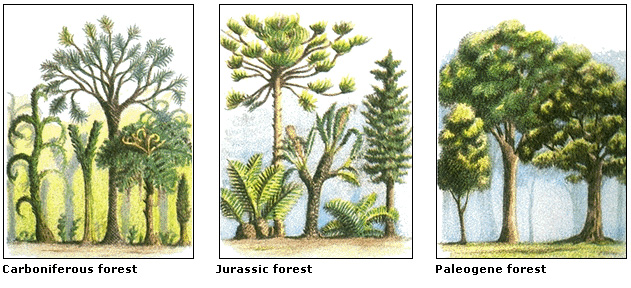

developed in marshlands about 385 million years ago, during the Devonian Period. They consisted of tree-sized club mosses and ferns, some of which had trunks nearly 40 feet (12 meters) tall and about 3 feet (1 meter) thick. These forests became the home of early amphibians and insects.

By the beginning of the Carboniferous Period—about 360 million years ago—vast swamps covered much of North America. Forests of giant club mosses and horsetails up to 125 feet (38 meters) tall grew in these warm swamps. Ferns about 10 feet (3 meters) tall formed a thick undergrowth that sheltered huge cockroaches, dragonflies, scorpions, and spiders. In time, seed ferns and primitive conifers developed in the swamp forests. When plants of the swamp forests died, they fell into the mud and water that covered the forest floor. The mud and water did not contain enough oxygen to support decomposers. As a result, the plants did not decay but became buried under layer after layer of mud. Over millions of years, the weight and pressure on the plants turned them into great coal deposits.

Later forests.

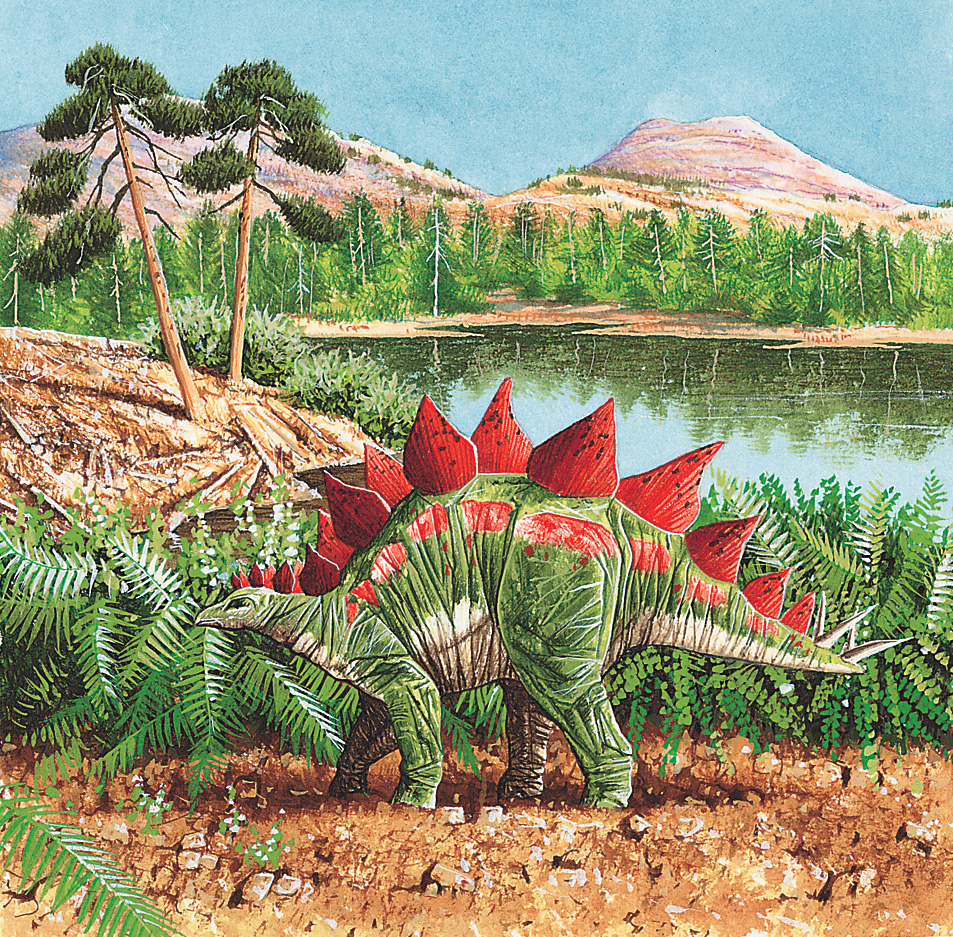

As the Mesozoic Era began, about 250 million years ago, severe changes in climate and in Earth’s surface wiped out the swamp forests. In the new, drier environment, gymnosperm trees became dominant. Gymnosperms are plants whose seeds are not enclosed in a fruit or seedcase. Such trees included seed ferns and primitive conifers like those that grew in the swamp forests. They also included cycad and ginkgo trees, which became widespread. Gymnosperm trees formed forests that covered much of Earth. Amphibians, insects, and large reptiles lived in these forests.

The oldest known fossils of flowering plants date to the early part of the Cretaceous Period, about 130 million years ago. Flowering plants, which are called angiosperms, produce seeds enclosed in a fruit or seedcase. Many angiosperm trees became prominent in the forests. They included magnolias, maples, poplars, and willows. Flowering shrubs and herbs became common undergrowth plants.

At the start of the Cenozoic Era, about 65 million years ago, Earth’s climate turned cooler. Magnificent temperate forests then spread across North America, Europe, and Asia. The forests included a wealth of flowering broadleaf trees and needleleaf conifers. Many birds and mammals lived in these forests.

Modern forests.

Earth’s climate continued to turn colder. By about 2.4 million years ago, the first of several great waves of glaciers had begun to advance over much of North America, Europe, and Asia. By the time the last of these glaciers had retreated—about 11,500 years ago—the ice sheets had destroyed large areas of the temperate forests in North America and Europe. Only the temperate forests of southeastern Asia remained largely untouched.

The forests of the world took on their modern distribution after the last of the glaciers retreated. For example, the great boreal forests developed across northern Europe and North America. But the world’s forest regions are not permanent. Today, for instance, temperate forests are invading the southern edge of the boreal region. Another ice age or other dramatic environmental changes could greatly alter the world’s forests.

Deforestation

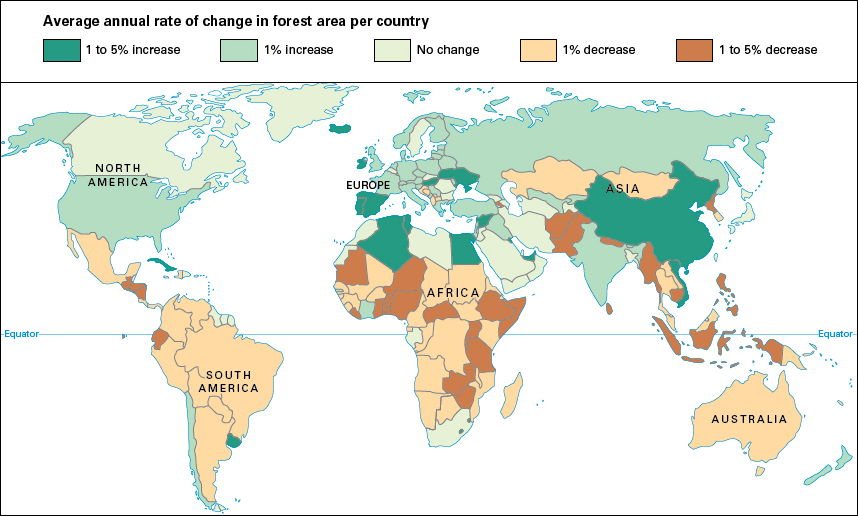

Human activities have had tremendous impact on modern forests. For at least 10,000 years, people have cut down forests to clear areas for farmland. Beginning in the 1800’s, great expanses of forest have also been eliminated because of logging and industrial pollution. The destruction and degrading of forests is called deforestation.

Severe deforestation now occurs around the world, even in the most remote rain forests and boreal forests. Until the late 1940’s, rain forests covered about 8.7 million square miles (22.5 million square kilometers) of Earth’s land. Today, they cover less than half that area. Millions of acres or hectares of rain forests are destroyed each year. Since 1800, huge areas of temperate forests have also been cleared. Many parts of eastern North America, for example, have less than 2 percent of even degraded forests remaining.

Industrial pollution is a chief cause of deforestation. Factories often release poisonous gases into the air and dangerous wastes into lakes and rivers. Air pollutants may combine with rain or other precipitation and fall to earth as acid rain (see Acid rain). Acid rain and polluted bodies of water can restrict plant growth or even kill most plants in a forest.

Massive deforestation has made many remaining forest tracts small, isolated islands. As forests become smaller, their ability to sustain the full variety of plant species decreases. Many forests are so seriously degraded by logging activities that they fail to regenerate replacement forests.

Loss of forests has helped create many ecological problems. For example, rain water normally trapped by the forests is causing more floods around the world. In addition, as forest areas decrease or degrade, the production of oxygen from photosynthesis also decreases. Oxygen renewal is vital to the survival of oxygen-breathing organisms. At the same time, as less carbon dioxide is taken up by photosynthesis, the amounts of carbon dioxide released into the air increases. Thus more heat from the sun is trapped near Earth’s surface instead of being reflected back into space. Many scientists believe that this greenhouse effect is causing a steady warming that could lead to threatening climatic conditions (see Greenhouse effect).

The destruction of forest ecosystems also destroys the habitats of many living creatures. Countless species of animals and plants have been wiped out by deforestation, and more are killed each year at an increasing rate.

To combat these problems, people and governments have been seeking out and protecting old growth forests that remain undisturbed by humans. Such protection enables scientists to conduct long-term research on how old growth forests sustain the variety of plants and animals that live there.