Forestry is the science and art of managing forest resources for human benefit. The practice of forestry sustains forest ecosystems—that is, the living things in an area and the relationships between them. Forestry also helps people take timber for the manufacture of lumber, plywood, paper, and other wood products. Forestry includes the management not only of trees, but also of other valuable forest resources. These resources include a forest’s water, its wildlife, its rare and endangered plants and animals, and the plants that grow beneath the trees.

In general, forests are managed with the goal of providing several benefits at once. This concept is called multiple use forest management. In the United States, this concept is applied in national forests, most state forests, and many private forests. In addition to furnishing timber, these forests may provide water for communities; food and shelter for wildlife; grazing land for livestock; and recreation areas for campers, hikers, and picnickers.

In some forests, however, the importance of one resource may outweigh that of others. For example, companies that manufacture wood products manage their forests primarily for maximum timber production. Other forests may be protected as parks or as wilderness or recreation areas.

This article discusses the scientific management of forest ecosystems. For information on the various products made from trees, see Forest products . For a discussion of forest ecology, see Forest .

Managing timber resources

One goal of managing timber resources is to achieve an approximate balance between the annual harvest and growth of wood. This balance, called a sustained yield, ensures a continuous supply of timber. Sustained yield is achieved by managing forests so they have areas of trees in each of several age groups, from seedlings to mature trees. The science of establishing, growing, and harvesting stands (large groups) of trees for sustained yield is called silviculture. Silviculture also focuses on growing and using trees for wildlife habitat, watershed protection, and other uses. Foresters study how various species (kinds) of trees grow in different climates and soils, and how much sunlight and water the trees need. Foresters also breed trees that have improved growth rates and greater resistance to diseases and pests.

Harvesting.

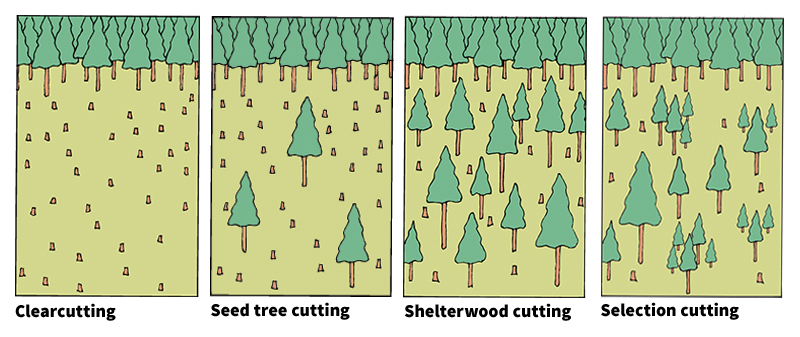

There are four silvicultural methods used in the harvest of timber: (1) clearcutting, (2) seed tree cutting, (3) shelterwood cutting, and (4) selection cutting. Each method is designed to provide an environment that favors the establishment of certain kinds of trees. New trees grow from seeds produced by the remaining or surrounding trees, from sprouting stumps or roots, or from seeds or seedlings that foresters plant.

Clearcutting

is the removal of all the trees in a certain area of a forest. It is generally used to quickly reestablish a stand. Regrowth after clearcutting may involve planting seeds or sprouting from stumps. Clearcut areas must be large enough to prevent surrounding forests from affecting the young trees growing within the clearcut opening. Aspen, jack pine, lodgepole pine, and paper birch are examples of commonly clearcut trees. Such trees regenerate quickly.

Seed tree cutting

resembles clearcutting, but foresters leave a few trees widely scattered in the harvested area to provide a natural source of seeds. These seed trees may be removed after a few years when the new stand is established. Seed tree cutting can be used with various conifer trees, including longleaf pine, western larch, and white pine.

Shelterwood cutting

involves harvesting timber in several stages over 10 to 20 years. Foresters establish a new stand as the old one is removed. Shelterwood cutting can be used to regenerate Douglas-fir, oak, ponderosa pine, and white pine, which require shade during their first few years of growth. It also allows the growth of some trees in a stand to continue after the majority of the trees have ceased growing well.

Selection cutting

is the harvesting of individual or small patches of mature trees to make room for new and younger trees. The trees are removed on the basis of their size, health, quality, and nearness to other trees. However, foresters leave most larger trees standing to produce seeds. Selection cutting leaves only small openings in a forest. It thus works best with trees that grow well in shade. Such trees include American beech, fir, hemlock, and sugar maple. Forests may be harvested by selection cutting every 10 to 30 years.

Planting.

Foresters may plant new trees in an area from seeds, or they may plant seedlings (young trees) that have been raised in a nursery. When foresters plant trees on harvested land or in an existing forest, the process is called artificial regeneration. When foresters plant trees in an area that was never covered by a forest, the process is called afforestation.

Seeds can be planted in various ways. In large areas that have been destroyed by wildfire, seeds can be spread across sites by hand, by machine, or even by airplanes and helicopters. Depending on the method, foresters usually sow up to 30,000 seeds per acre (75,000 per hectare) to ensure adequate tree growth.

Forests are planted with seedlings in late winter or early spring, before the buds of the seedlings have opened for the growing season. Seedlings grow in a nursery for one to four years before being transplanted to the forest. Depending on the seedlings’ sizes, foresters generally plant between 500 trees and 2,000 trees per acre (1,250 and 6,250 trees per hectare). They use hand tools or planting machines. A person can plant between 1 and 3 acres (0.4 and 1.2 hectares) a day by hand. Machines can plant much faster, but they only work well on level ground.

Tree improvement

involves breeding trees for superior growth rates and increased resistance to diseases and pests. Foresters begin this process by searching forests for the straightest and fastest-growing trees of the species. These trees must also have high-quality wood and be healthy and free of harmful insects and other pests. Tree improvement programs have been used for black walnut, Douglas-fir, loblolly pine, and several other species.

After foresters find a superior tree, they take cuttings, called scions, from its branches. The scions are brought to a nursery and grafted (joined) to the roots of very young trees (see Grafting ). The scions receive nutrients through the roots of the trees but keep the characteristics of the tree from which they were cut. Foresters may use the grafted scions in reforestation. They may also take pollen from the male flowers to pollinate female flowers of scions from other superior trees. The foresters keep careful records of the scions used for each pollination.

After pollination, the female flowers yield seeds that are planted in the nursery to produce seedlings. Foresters transplant the seedlings into special plantations and closely measure the growth of the trees. If the trees from a particular set of parents appear to grow quickly with superior characteristics, the seeds from those parents may be produced commercially for reforestation.

Community forestry,

also called social forestry, is a system of forest management that treats woodlands as a community resource. In some regions, including parts of North America and northwestern Europe, forests have been set aside for community use for hundreds of years. Rural communities in many developing countries practice community forestry to provide themselves with fuel wood and timber and with food from forest plants and animals.

Community forestry takes many forms. In village woodlots, trees are grown for firewood on spare patches of land. Agroforestry involves techniques that produce trees in combination with crops, animals, or other products. In intercropping, cereals, vegetables, and fruit are grown between rows of newly planted trees until the trees grow too tall and overshadow them. Silvipasture involves managing tree growth through controlled forest grazing by animals. Multiple-product forestry utilizes techniques designed to increase the yield of fruit, wild game, honey, and many other forest commodities in addition to timber.

Managing other forest resources

Water.

All forests grow within watersheds—that is, regions that supply water for rivers and streams. Forest soils collect water by soaking up rain and melted snow. The soil of a forest is covered by a spongy layer of leaves and twigs, called litter. The action of earthworms, insects, rodents, and decaying roots creates open spaces within the soil. When rain or snow falls, the water fills these spaces and is absorbed by the litter. Much of the water is used by plants, and some flows underground and then into rivers, streams, and wells.

Watershed management largely involves keeping forest soil porous (filled with open spaces) so it can absorb a large amount of water. Proper forest harvesting reduces the water lost and so increases the underground supply and flow of water. If forest soils are not managed carefully, the soil will become hard and nonporous. Water flows over the surface of such ground, carrying mud and other materials into nearby streams and lakes. This runoff damages other soil, pollutes the water of the streams, and may even cause flooding.

Foresters help keep soil porous in several ways. They reforest harvested areas quickly to assure a continuous supply of litter. They ensure that roads built for logging operations are carefully designed to prevent soil erosion. Foresters also regulate livestock grazing to maintain a good cover of grass and to prevent the animals from packing down the earth.

Wildlife.

Forests provide homes for a wide variety of wildlife, including bears, birds, fish, and rodents. Forest wildlife management involves maintaining a balance between the number of animals in a forest and the supply of food, water, and shelter.

Dense forests of old, tall trees provide good homes for birds, insects, and such climbing mammals as raccoons and squirrels. But the shade in such forests prevents the growth of enough herbs, shrubs, and small trees to feed large animals that live on the ground. However, openings made in the forest during the timber harvest allow more sunlight to reach the forest floor. New plants sprout in the clearings, providing food for wildlife. Hollow trees may be left in large openings to serve as dens and nesting places.

Wildlife management also involves controlling animal populations by regulating hunting. Hunting can help control large populations of deer, elk, and other animals that can degrade forest ecosystems by damaging trees and reducing ground cover.

Rangeland.

Many forests in dry regions have widely spaced trees with heavy undergrowth of grass and shrubs. Ranchers often graze livestock in such areas. The use of such rangeland must be carefully regulated to prevent overgrazing, which can damage tree roots and erode the soil. Foresters manage grasslands by controlling the number of livestock in a given area. Foresters may require ranchers to move livestock away from land that is heavily grazed to new pastures. These actions prevent the animals from eating too much grass in any one area.

Recreation areas.

The scenic beauty and natural resources of forests provide opportunities for many recreational activities, including camping, fishing, hiking, and hunting. Millions of people visit state and national forests annually. Forest-products companies and private landowners also may open areas of their woodlands to the public.

Many areas of national and regional forests are managed primarily for recreation. Foresters carefully plan these areas to provide benefits to visitors with minimum harm to the forests. For example, before developing a campground, foresters study such factors as the terrain, the amount of shade, and the availability of water in the area. They can then install picnic tables, cooking equipment, electrical outlets, plumbing, roads and trails, and parking areas without seriously upsetting the ecological balance of the forest.

Fire and forests

Most scientists consider forest fires an essential natural process. Although fire can cause great destruction, it produces great ecological benefits. Fires recycle nutrients—that is, substances that plants need for growth. Fires clear trees and other vegetation that can prevent new tree growth. In fact, some pine and oak species actually grow best when forest fires occur. To take advantage of such benefits, foresters permit certain types of fires to burn. Prescribed fires are set by fire crews in safe conditions with low winds and high humidity, far from human dwellings.

Other fires, especially those that endanger lives or property, are referred to as wildfires. Wildfires are generally fought quickly and aggressively. Some wildfires are caused by lightning strikes. But most are caused by human beings. The fires may be started accidentally or deliberately. During dry seasons, when fires can easily start, foresters may restrict open campfires or even close a forest to the public to reduce the danger of fire. Foresters may watch for fires from lookout towers, or they may patrol forests by airplane.

To extinguish a wildfire, firefighters must remove the blanket of litter and dead wood from the forest floor. These materials serve as fuel for fire. Firefighting crews spray water or chemicals on the burning area to cool the fire and slow its progress. They then can get close enough to the flames to dig a fireline, also called a firebreak. Firefighters start a fireline by clearing all logs, brush, and trees from a wide strip around the fire. They then scrape away the litter and some of the soil with axes, shovels, or bulldozers. Highly trained firefighters called smoke jumpers may parachute from airplanes or helicopters to dig a fireline in an area that is difficult to reach by land.

After creating a fireline, the firefighters may set backfires to burn the area between the line and the forest fire itself. Backfires remove additional fuel and widen the fireline to help stop the spread of the flames. After a fire dies, the firefighters clear any flammable material from the edge of the burned area. This action prevents the material from smoldering and starting new fires.

Protecting forest ecosystems

The full benefits of forest ecosystems can be obtained only if they are protected from diseases, insect pests, and invasive species. Many countries have passed legislation designed to protect forest resources in other ways. Such laws control how roads, buildings, and industrial facilities are built in forests. They also give governments powers and funds to fight forest fires, pests, and diseases, and to regulate timber production.

Diseases and pests.

Most tree diseases are caused by fungal infections. Such infections may enter the tree directly, or they may enter through an insect carrier. Diseases attack trees chiefly by clogging the flow of sap, killing the leaves, or rotting the roots or wood. Insects damage trees either by feeding on inner bark, by sucking the fluid from the leaves or stems, or by eating the leaves. Insects that eat tree leaves are called defoliators. Most native diseases and pests only occasionally become problems, usually when stands are old or unhealthy.

Foresters control diseases and pests by three chief methods: (1) biological controls, (2) silvicultural controls, and (3) direct controls. Biological controls fight diseases and pests with their natural enemies. For example, foresters might control an insect pest by spraying a forest with a disease organism which affects that particular species of insect. Silvicultural controls use methods of timber management to make a forest undesirable for diseases and pests. For example, foresters may remove old, weak trees that are easy prey for fungi and insects. Direct controls include the use of chemical pesticides to kill fungi and insects. Such chemicals can kill nontarget plants and animals, and so pesticides are generally used only if other controls fail.

Invasive species

pose one of the most substantial threats to forests. Invasive species are nonnative plants, animals, and microbes that cause environmental and economic harm to ecosystems. These species are often accidentally transported between countries in nursery and horticultural products or undetected in overseas shipping containers. Many of the most severe forest diseases and insects are invasive. Invasive diseases include beech bark disease, chestnut blight, Dutch elm disease, sudden oak death, and white pine blister rust. Invasive insects include the Asian long-horned beetle, emerald ash borer, spongy moth, and hemlock woolly adelgid. Each of these invasive species has caused or could potentially cause the loss of a tree species from forests in large parts of North America.

Invasive plant and animal species also can cause significant damage, although the damage may occur more slowly. For example, invasive wild boars have caused significant damage to forest floor plants throughout Hawaii and much of the southeastern United States. Bush honeysuckle, garlic mustard, kudzu, multiflora rose, and salt cedar are several of the many invasive plant species that have displaced native forest plants dramatically changed forest ecosystems.

Foresters deal with invasive species in many ways. Often, foresters use pesticides to control their spread as invasive species can be difficult to control with other methods. Foresters may use prescribed fire or biological controls. Foresters also try to prevent invasive species from being introduced and spread in the first place. This prevention includes banning the transport of seeds, firewood, and other plant material from region to region.

History

People have relied on forests since prehistoric times. Many scientists believe deforestation led to the decline of many early civilizations. But throughout history, cultures learned to regulate the use of forests to prevent shortages of timber. During the Middle Ages, from about the A.D. 400’s through the 1400’s, forest wildlife was protected to ensure a sufficient supply of game for the nobility to hunt. In the 1500’s, people in France and some German states began setting aside forest plantations for timber cutting and other areas for growing new trees to replace those being harvested. Forest management methods soon spread throughout Europe. In the 1700’s and 1800’s, the first colleges teaching forestry subjects opened in France and Germany.

In North America, the early settlers treated the vast timber resources as though they would last forever. They cleared much more land than they needed for their homes and crops and destroyed large areas of forestland by using wasteful logging methods. By 1891, a conservation movement had started, and the United States Congress authorized the president to set aside wooded areas called forest reserves. The U.S. Forest Service was established in 1905. The service was given control of the forest reserves, which in 1907 became known as national forests. The Canadian Forest Service was established in 1899.

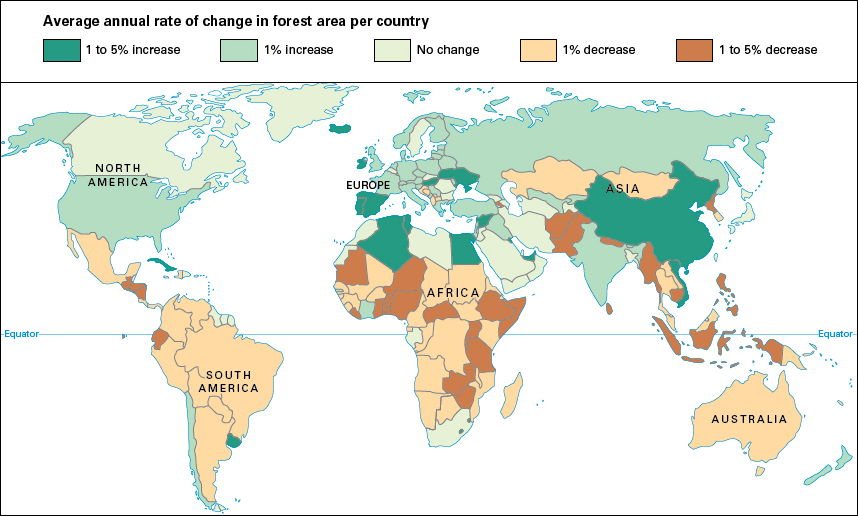

Since the mid-1900’s, logging and the expansion of agriculture have damaged or cleared vast areas of the world’s rain forests. Deforestation has largely occurred in less developed nations as they have sought to secure short-term economic benefits. Deforestation continues in many such places today. Worldwide conservation organizations have begun working with local governments to promote sound management of tropical forests by the people who use them. Conservationists have also sought to include large areas of intact tropical forest in parks and reserves that will protect such ecosystems for future generations.