Handwriting is one of the most useful skills. A person who has learned to write can put thoughts on paper for others to read. Handwriting plays a vital part in communication, and is one of the most important ways of keeping ideas ready for use. People can forget. But handwriting helps them remember. They can use pen or pencil to mark down letters, numbers, and other signs. People can move to another town, city, or country, but handwriting lets them “talk” to one another. The art and practice of attractive handwriting is called penmanship, or calligraphy (see Calligraphy ).

The importance of handwriting

Some people believe that typewriters, computers, and printing presses have made handwriting unimportant. But it is still a necessary skill for everyone. When people write letters, they may want to write about their own ideas and feelings, or about their friends and families. A handwritten letter has a personal touch, because no two people have exactly the same handwriting.

Handwriting has other important uses. Students use handwriting to record and organize ideas they hear in lectures and classrooms. Later, they can use their notes for study and discussion. Secretaries of clubs usually write down important happenings at meetings. In school, students often write reports and tests by hand. Business executives, doctors, teachers, and many other adults keep records and make notes by hand. Later, they may have these ideas typewritten or printed.

Just being able to write is not enough. A person must also write legibly, so the words can be read. Handwriting that no one can read is useless and can create serious problems. For example, a student may write the correct answer to a question on a test. But if the teacher cannot read the answer, it may be marked wrong. An unclearly written check may result in serious financial loss. If a clerk writes a sales ticket so that the person delivering the package cannot read the ticket, it may delay the delivery and produce a dissatisfied customer.

Kinds of handwriting

In most schools, students are taught two kinds of handwriting—manuscript writing and cursive writing. Some writing systems combine manuscript and cursive letter forms for beginning writers. For details, see the Handwriting Systems section in this article.

Manuscript writing

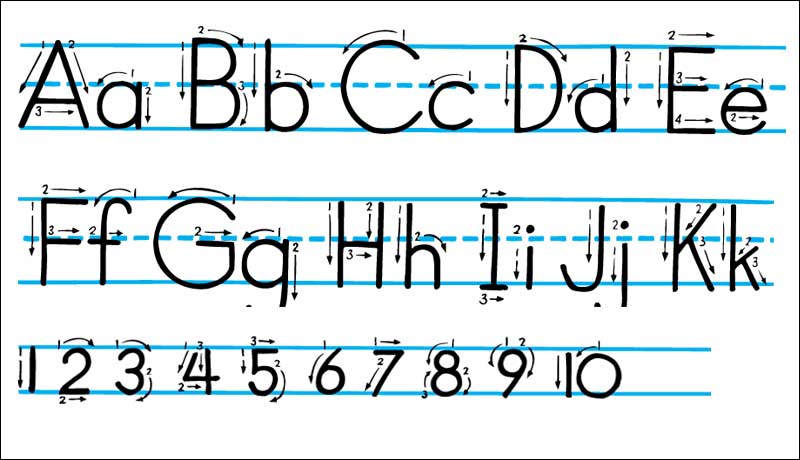

is a kind of handwriting most often learned by schoolchildren who are just beginning to write. It looks much like printing in a book. Each letter is straight up-and-down, and not joined to the next.

Teachers find that learning to write is not always easy for young children. Most teachers prefer a way of writing that places as little strain as possible on a child’s first efforts to put ideas down on paper.

Young children find manuscript easier to learn than cursive writing, the more difficult method used by adults. Manuscript writing is easier, chiefly because it makes only limited demands on the ability to use arm, hand, and eyes together effectively. Young children can easily make the simple curves and straight lines of manuscript letters. They can learn clear, easy-to-read handwriting quickly.

Manuscript also comes naturally from a young child’s experiences with printed words. A youngster usually begins to do some reading before learning to write. Children read their teacher’s manuscript writing on the chalkboard. In books, they read printed words that look much like manuscript words. So they know the letters with which they begin their own manuscript. At the same time, learning manuscript helps them learn to read and to spell. By the time children begin cursive writing, usually they can write fairly well in manuscript.

Cursive writing

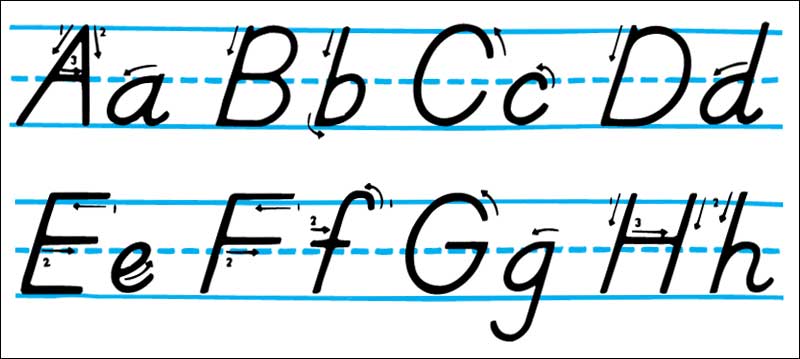

is used by most adults. Boys and girls usually learn cursive writing after they have mastered manuscript writing. The word cursive means running. In cursive writing, the letters join, or run together, instead of being separated as in manuscript. Also, the letters are slanted.

Some people use both manuscript and cursive writing. They may use manuscript to make signs, labels, and charts. They use cursive writing for their personal letters and notes.

Learning to write

Beginners should aim for easy-to-read handwriting. At the same time, they should try to attain a fair degree of speed. But teachers advise caution in trying to gain speed. Too much pressure to increase speed may hamper both clear writing and careful thinking.

Writing readiness.

Children usually begin to learn to write in kindergarten or first grade. Sometimes children learn some handwriting even before entering school. If so, parents or teachers should make sure that children learn in the same way they will learn later in school. Also, they should be sure that the child is ready to learn.

A strong interest in writing is one of the most important signs of a child’s readiness to learn to write. This interest often results from seeing adults and other children write at home and in school. But interest is not enough. Eye, hand, and arm control must be developed so that the child can manage paper and pencil. Coloring, drawing, and many kinds of play help build control. Puzzles, nesting toys, lacing frames, and similar playthings can help. A child also needs a strong sense of left and right. Otherwise, reverse writing or other problems may occur. Games and simple dances help develop a sense of left and right. Most of all, the child must want to say something on paper and must be able to read what was written down. A child’s readiness to read is usually an important clue that readiness to write will soon appear (see Reading ).

Learning manuscript writing.

When handwriting instruction begins, teachers usually encourage boys and girls to express their own ideas in writing. This kind of learning is called functional, because it puts handwriting to work at once. Teachers hold practice periods on letters only as long as necessary. These practice periods help students learn the different shapes and strokes required for letters.

In this kind of learning, children sometimes use oversized pencils. But many handwriting experts believe that ordinary pencils serve just as well. The writing paper has lines 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) apart. Halfway between these lines, there may be lines of another color, or dotted lines, that help in writing both capital and lower case (small) letters. Often, the teacher writes model letters on the chalkboard for the children to practice. The students may practice new letter shapes and words on the chalkboard before trying them on paper.

The opportunity to watch the teacher write is important in learning manuscript writing. The teacher shows in clear, easy-to-follow strokes just how to write. Each letter is made with the same strokes in the same order every time it is written. The teacher may use the same words each time to name the strokes for the students. For example, when making the letter “a“, the teacher may say, “Around, straight down.” In general, the curves and straight lines that make up the letters are made from the top of the letter downward. The children learn to check the shape, size, and spacing of the letters.

The child should hold the chalk or pencil in a way that fits the hand naturally. No two children can hold pencil or chalk exactly alike. Some have hands that are long and thin. Others have short, wide hands. The paper is placed straight up-and-down for manuscript writing. For cursive writing, the paper slants to the left for people who are right-handed. For left-handed people, the paper slants to the right. The child should sit up straight, squarely in front of the table or desk, with both feet flat on the floor.

Learning cursive writing.

Children should make the shift from manuscript to cursive writing only after they have gained a fair mastery of manuscript. The change usually occurs in the late second or third grade. In some cases, a later time makes the shift less difficult. At any grade level, the shift should be made gradually. It may require an average of four to six weeks. But children with varying abilities should be permitted considerable difference in the required time.

Learning cursive writing once consisted of practicing individual letters. Children practiced until they could make an exact copy of the letter from the chart, manual, or chalkboard. Today, the goal is still the development of clear, well-formed letters. But the child begins writing stories and reports soon after learning the letters. In this way, the child makes practical use of writing skills as soon as possible instead of delaying while striving for perfect letter shapes.

As in manuscript writing, students learn the most about cursive writing by watching a teacher write well. They can see how the paper is slanted to give slant to the writing. They learn which letters are made differently in cursive writing than in manuscript. The students also learn how to make the joining strokes between letters. They are taught not to raise the pencil from the paper until an entire word is finished. Then, they dot the “i’s” and cross the “t’s.”

Handwriting systems.

Teachers can use one of several systems to teach handwriting. Materials for these systems are prepared by various companies.

Since the mid-1900’s, some companies have developed writing systems that combine manuscript and cursive letter forms for beginning writers. One of the best-known systems combining letter forms is D’Nealian handwriting, which was introduced in 1978. D’Nealian manuscript letters are oval and slanted. They more closely resemble cursive writing than conventional manuscript. This resemblance is intended to make cursive writing easier for children to learn. D’Nealian cursive letters look like those of other writing systems.

Research concerning handwriting techniques has shown no evidence that one particular system of handwriting is better than any other. Researchers have concluded that the individual instructor’s skill plays the most important role in teaching a child to write.

Left-handedness.

About 12 percent of all people are left-handed. When left-handed children begin to learn to write manuscript, they may need some special help from the teacher. A left-handed child should hold the pencil so that the fingers are at least 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) from the point. This grip gives the child a better view of the paper while writing. Sitting at a desk or table that is slightly lower than normal height also may help. Left-handed children should be encouraged to keep the left arm close to the body when writing.

A left-handed child learning cursive writing may place the writing paper toward the left side of the desk, turned in a clockwise direction. Because it is difficult for left-handed children to slant their writing to the right, they should be allowed to write without a slant or to slant their writing to the left.

Teaching methods for left-handed children may include group lessons with a left-handed person demonstrating the writing technique. Practicing at the chalkboard also may be useful.

Common handwriting problems

The main goal for easy-to-read handwriting consists of good letter formation. The letters a, e, r, and t seem to cause difficulty. But in all letter forms, a few strokes determine whether or not a letter will be clear. Too much spacing between letters and irregular slanting of letters may also result in poor handwriting.

In general, a person who wants improved handwriting should correct these common problems. But someone may have to help the person find the difficulties and correct them in the right way.

History

Early forms of writing.

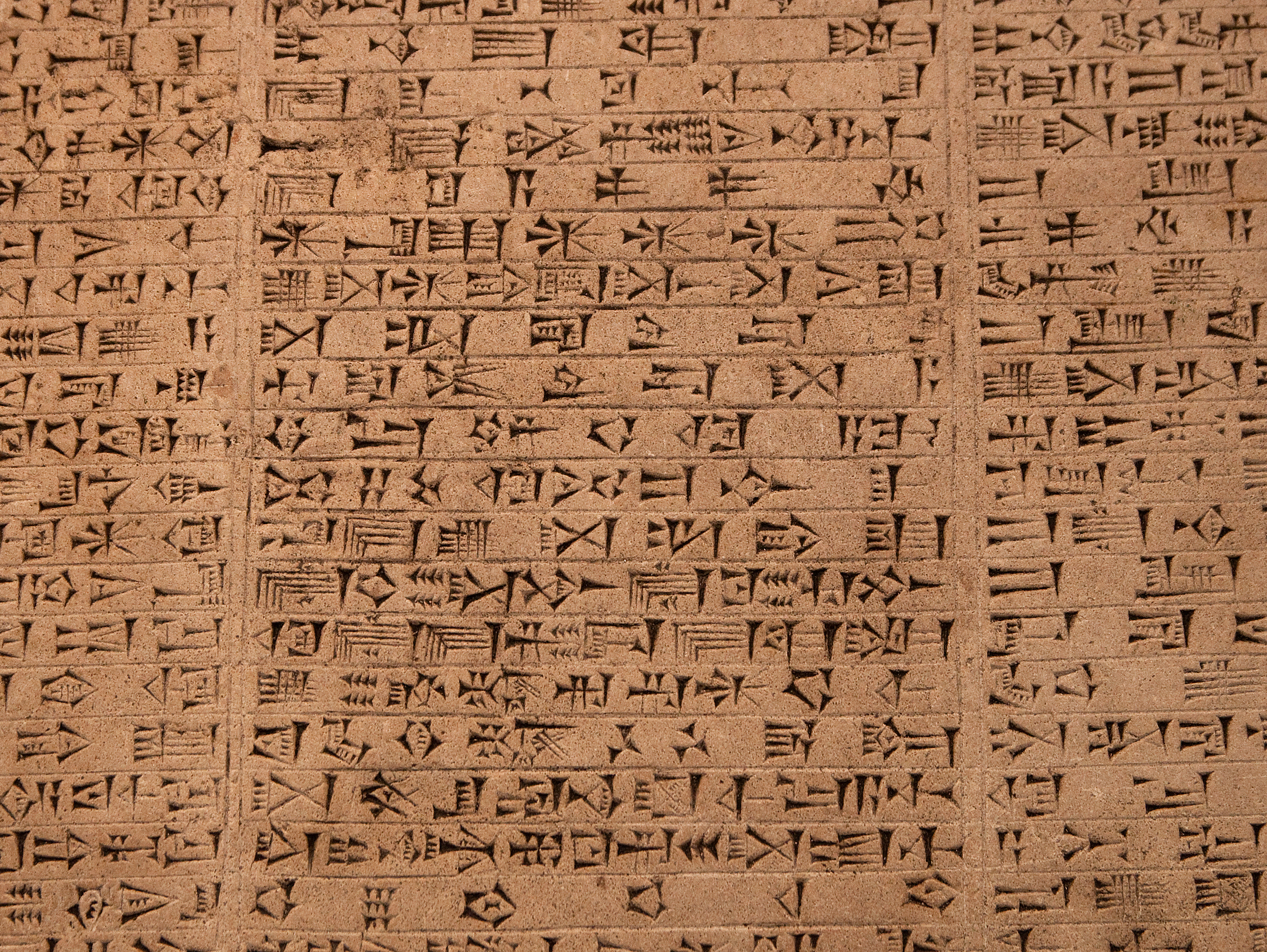

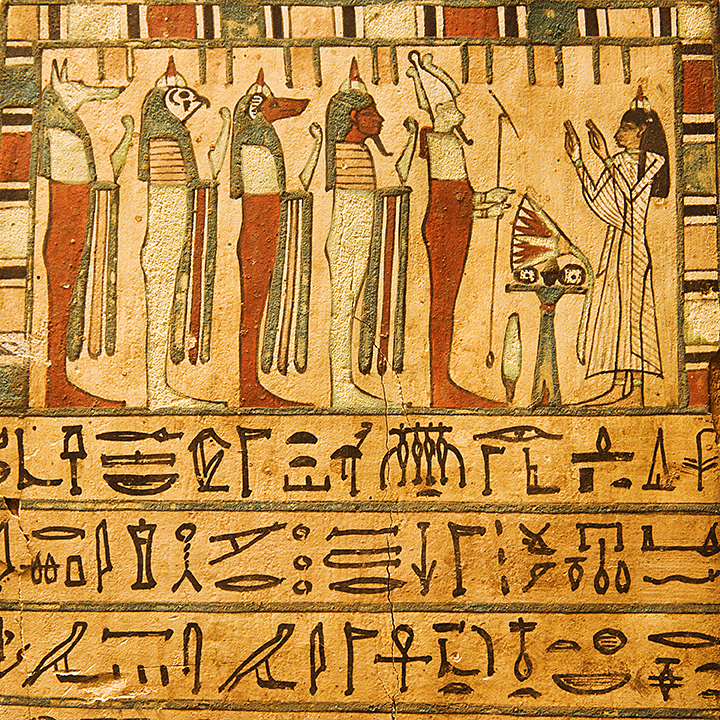

Prehistoric people invented the first crude “writing.” They drew pictures of wild animals on the walls of caves and rock shelters. Their pictures tell the story of how they hunted for food (see Prehistoric people ). Later peoples made their pictures simpler and simpler. The pictures gradually became signs called pictographs (see Pictogram ). Each pictograph stood for a word or an idea. This kind of picture writing probably reached its highest point about 3000 B.C. in Egypt. The Egyptians used a kind of picture writing called hieroglyphics (see Hieroglyphics ). In about 3300 B.C., the Sumerians invented a system of writing that used wedge-shaped symbols called cuneiform (see Cuneiform ).

About 1500 B.C., Semitic people in the Middle East invented the alphabet. In the alphabet, a written sign stands for a sound in the spoken language. For example, the letter b represents a certain sound. The Phoenicians developed the alphabet further. The Greeks took it over from the Phoenicians, and the Romans borrowed it from the Greeks. For more information on the history of the alphabet, see Alphabet and the separate articles on each letter of the alphabet.

In ancient times, few people knew how to write. Most of the people who wanted to send letters dictated them to people called scribes, who made their living writing for the public (see Scribe ).

Both manuscript and cursive writing come from the Roman alphabet. In fact, we write a number of letters almost exactly as the Romans wrote them. In printing, the term roman refers to straight up-and-down letters similar to those used in manuscript writing. The Romans used letters like these for inscriptions on monuments and public buildings. Printers use the term italic for letters that slant to the right, similar to those used in cursive writing. Printing in italic letters began in Venice, Italy, during the 1500’s. Several styles of cursive writing developed at this time.

Later writing styles.

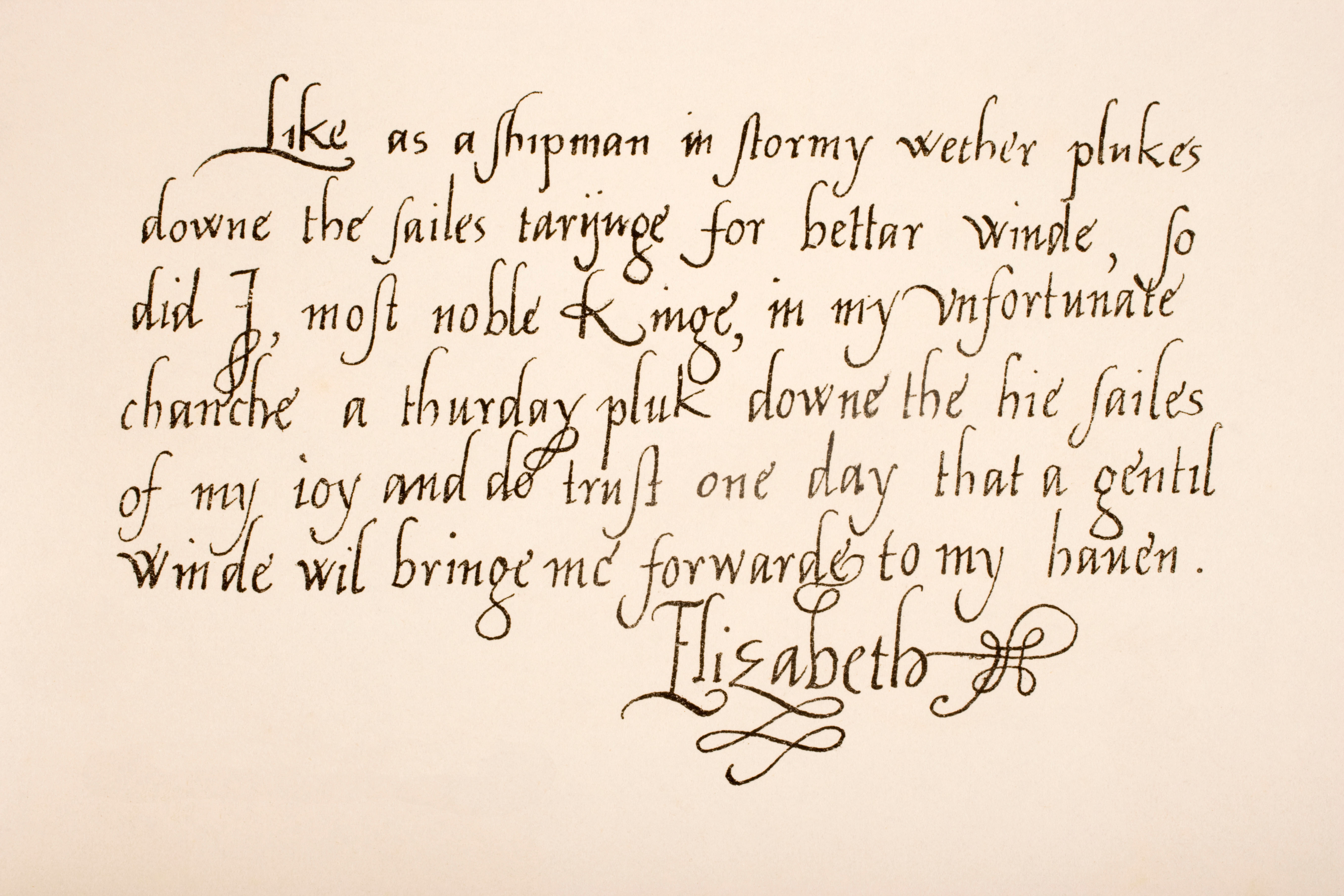

During the Middle Ages, monks in monasteries produced beautiful books written entirely by hand. They decorated the pages with fancy letters, borders, and pictures. Many museums treasure these books as masterpieces of writing. The monks often used a kind of writing called Gothic or black-letter. Today, people sometimes use this kind of writing on diplomas.

During the 1700’s and 1800’s, schoolchildren in Europe and the United States learned beautiful, but complicated, styles of cursive writing. English Round Hand, or Copperplate, became popular in the 1700’s.

During the 1800’s, schools in the United States taught a fancy style of writing with many loops and curves. This Spencerian style took its name from Platt Rogers Spencer (1800-1864), an American teacher who published many textbooks on penmanship. Children in the 1800’s worked long and hard to perfect a “fine Spencerian hand” in their writing.

The 1900’s.

During the 1900’s, schools in the United States and the United Kingdom began to use simpler styles of writing, particularly manuscript writing for beginners. Cursive writing was also treated less as an art and more as a practical tool. As a result, the term penmanship dropped out of common usage because it carried the outdated idea of writing as an exercise in beauty for its own sake. Teachers began to aim more at developing ideas in clear form. Practice methods shifted from depending heavily on separate exercises to developing good handwriting through the writing of letters and reports. Today, the purpose of learning to write is communication. Teachers help individual children check their own writing and make it more legible and fluent.