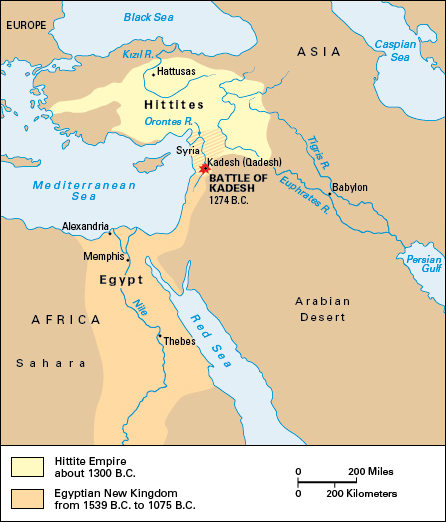

Hittites, << HIH tyts, >> were among the earliest inhabitants of what is now Turkey to be recorded in history. They began to control the area about 1900 B.C. During the next several hundred years, they conquered parts of Mesopotamia and Syria. By 1500 B.C., the Hittites had become a leading power in the Middle East. The Hittite language was Indo-European. Most scholars believe the Hittites came from central Asia north of the Black Sea and entered Turkey well before 2000 B.C. See Language (Indo-European).

Way of life.

The term Hittite refers to a mixture of Indo-European and indigenous (native) elements. Neighboring peoples influenced many aspects of Hittite architecture, art, literature, and religion. The Hittites’ legal system was fair and humane, and their law code emphasized compensation for a wrong, rather than revengeful punishment. The Hittites often established peaceful and profitable relations with the peoples they conquered. Their military superiority resulted from innovations. For example, they changed the design of chariots so that the chariots could carry three fighters rather than two.

The Hittites used the Akkadian language for their international correspondence. For their own royal and religious writings, they used the Hittite language, which they recorded in cuneiform script borrowed from the Mesopotamians. Scholars deciphered the Hittite cuneiform in 1915. The Hittites also used an indigenous hieroglyphic script for large, public inscriptions. These inscriptions were written in a dialect called Luwian. Luwian hieroglyphs probably had a wider appeal among the general population than the other forms of writing had.

History.

About 1750 B.C., a Hittite king united a number of independent city-states (cities and their surrounding territory) into one kingdom for the first time. One of these city-states was Hattusas (also spelled Hattusa or Hattusha), just east of present-day Ankara, Turkey. Hattusas became the Hittite Empire’s capital about 1650 B.C.

The Hittites conquered Babylon about 1595 B.C. They also gained control of northern Syria. The widow of an Egyptian pharaoh, probably Tutankhamun, asked the Hittite emperor to send one of his sons to be her husband and pharaoh of Egypt. But a group of Egyptians who did not like this arrangement murdered the son before the marriage.

Phrygian tribes from southeastern Europe soon began migrating from their homes in the Balkan Peninsula into the western part of the Hittite empire. As a result, the Hittites had to abandon Hattusas soon after 1200 B.C. The empire broke up and the Hittite language and its cuneiform disappeared. However, Hittite city-states that used the Luwian dialect and the Hittite hieroglyphic script continued to exist in southeastern Turkey and northern Syria. These city-states were not powerful, and they became part of the Assyrian Empire about 700 B.C.

The Hittites are mentioned several times in the Old Testament. Abraham bought the field and cave of Machpelah from Ephron the Hittite as a burial place for his wife, Sarah. Abraham’s grandson Esau married two Hittite wives. As late as the time of David, certain people of Israel were called Hittites. David had Uriah the Hittite killed in battle so that he could marry Uriah’s wife, Bathsheba. Most of the Hittites referred to in the Old Testament were the Hittites who lived in the later Syrian city-states.