Hydrothermal vent is a place where heated water flows from the ocean floor. Scientists have identified hydrothermal vents at a range of depths. Vents have been found in the shallow water around volcanic islands. They have also been found more than 12,000 feet (3,600 meters) beneath the ocean’s surface.

Hydrothermal vents occur wherever there is volcanic activity under the ocean’s surface. Most such activity occurs near the boundaries between tectonic plates. Tectonic plates are the rigid pieces that make up Earth’s rocky outer shell. The best-known vents appear along mid-ocean ridges. These ridges are volcanic regions where two oceanic plates are spreading apart. Vents also occur along boundaries where one plate sinks beneath another. In addition, they appear at hot spots. Hot spots are areas of volcanic activity that can be far from plate boundaries. In all three types of regions, magma (molten rock) is found below the sea floor.

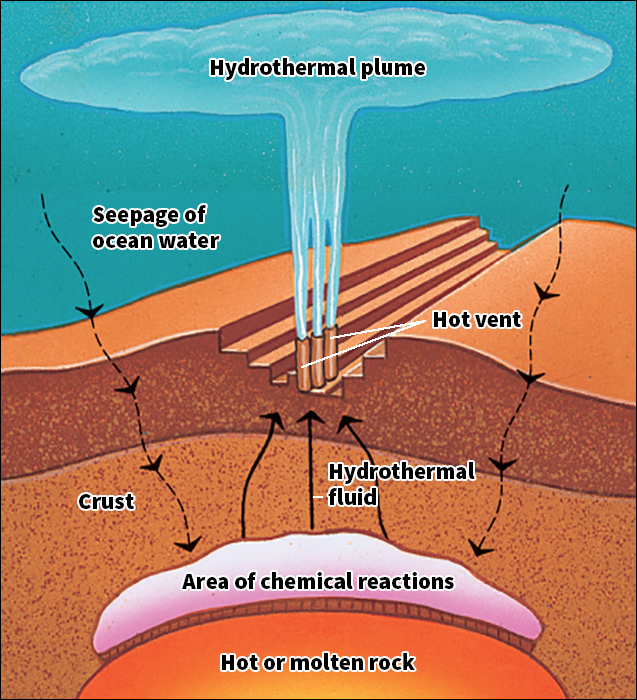

Hydrothermal vents form when seawater seeps down through the ocean floor into the hot rock surrounding pockets of magma. The rock can heat the water to about 660 to 840 °F (350 to 450 °C). The hot seawater and rock also react chemically. The water grows more acidic. It also becomes rich in hydrogen sulfide and metals dissolved from the rock. The hot water rises through mineral-lined conduits (channels in the rock) to flow from the vents.

At some vents, often referred to as hot vents, the water rises through a narrow conduit. This water retains much of its heat when it reaches the sea floor. At other vents, called diffuse vents, rising hot water first combines with cold seawater in cracks and cavities in the rock. The resulting cooler water then spreads out and rises through many conduits. At these vents, the water emerges from a broader area of the sea floor.

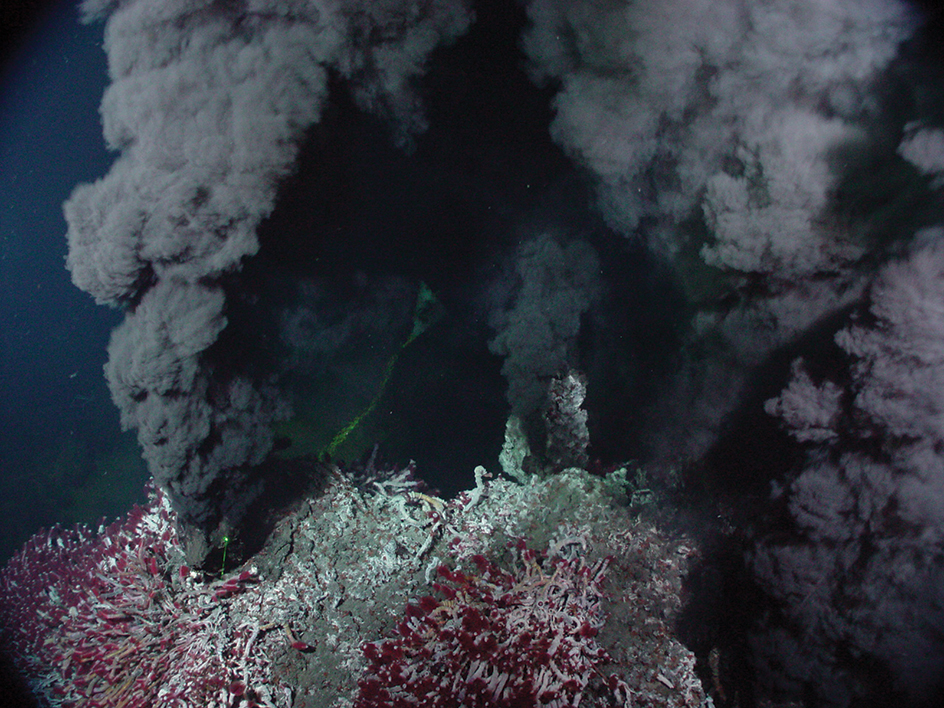

The hot water leaving a vent mixes with cooler ocean waters. As it does, the dissolved metals and sulfur rapidly combine into minerals called metal sulfides. These minerals can form billows of fine, dark particles resembling smoke. For this reason, hot vents that release high concentrations of metal sulfides are often called black smokers. Over time, minerals from vent waters can build up around a vent to form striking deposits called chimneys.

Some deep-sea vents support diverse and exotic communities of marine life. The food chain of these communities differs significantly from that near the surface. A food chain is the system by which energy is transferred from one living thing to another in the form of food. The food chain near the surface is based on photosynthesis. Photosynthesis is the process by which plants and other living things use sunlight to create food. But creatures near deep-sea vents rely on specialized microbes that produce food from chemicals in vent waters. This process is called chemosynthesis. Some of these microbes, called hyperthermophiles, live in temperatures near or above that of boiling water (212 °F, or 100 °C). Some vent animals, such as giant tubeworms and mussels, harbor chemosynthetic microbes in their bodies. The microbes produce food for the animals in a relationship called symbiosis that benefits both organisms.

Not all vents form directly over volcanic heat sources. In 2000, oceanographers found a new kind of vent that releases water heated in part by a chemical reaction. In a process known as serpentinization, seawater reacts with a rock called peridotite, releasing heat. The resulting vent water is less acidic and contains less metal than that released by volcanic vents. The vents produce large, slow-growing chimneys. These chimneys are made up primarily of the mineral calcium carbonate.