Arctic is the northernmost region of Earth. It surrounds the North Pole and includes the northern areas of North America, Europe, and Asia. Some parts of the Arctic are freezing, barren landscapes that cannot support much life. During winter, the sun never rises above the horizon in much of the Arctic. But during the brief Arctic summer, the sun never sets, and life flourishes in some places. The word Arctic comes from Arktos (bear), the ancient Greek name for a constellation that appears in the northern sky.

The southernmost parts of the Arctic border a vast band of evergreen forests called the taiga. Farther north, trees cannot grow, and the landscape consists of dry, frozen plains called the tundra. Herds of caribou migrate seasonally between the tundra and the taiga. In the rocky, windswept lands north of the tundra, few plants can survive. Arctic lands encircle the Arctic Ocean, which remains mostly frozen all year. The North Pole lies in the Arctic Ocean.

Despite the challenging environment, people have found ways to adapt to life in the Arctic since ancient times. The indigenous (native) peoples of the Arctic include the Inuit (sometimes called Eskimos) of North America and the Sami of Europe. English, Dutch, and Russian explorers arrived in the Arctic later.

Underground, the Arctic is rich in minerals, natural gas, and petroleum. Today, global demand for petroleum and gas drives much Arctic exploration.

This article will discuss the Arctic’s land, climate, and natural resources; the traditional ways of life of Arctic peoples; and the history of Arctic exploration. The final section deals with challenges facing the region today

Land and climate

Scientists and governments define the Arctic in several different ways. Politically and culturally, the Arctic can be defined as the lands north of the taiga. Defined this way, it includes the northern parts of Alaska and Canada; northern Scandinavia (Norway and Sweden); northern Finland; and Russia’s Siberia region. It also includes Greenland and most of Iceland.

Another common definition limits the Arctic to the region north of the Arctic Circle, an imaginary line that circles the globe at 66°33’ north latitude. The Arctic Circle marks the edge of an area where the sun stays above the horizon one or more full days each year, a phenomenon known as the midnight sun.

Many scientists define the Arctic as the northern region with an average July temperature lower than 50 °F (10 °C). The boundary of this region is called the 50 °F (10 °C) July isotherm. An isotherm is an imaginary line defined by a common temperature. Under this definition, the Arctic includes some lands south of the Arctic Circle, but not some lands north of the Arctic Circle.

Climate.

The Arctic climate is cold because the area receives relatively little energy from sunlight. In winter, the sun never rises during the day in some places. Even when the sun is shining, the sunlight is less direct and thus less intense than that farther south. Without sunlight, winter temperatures may drop below –76 °F (–60 °C). But in the constant sunlight of summer, temperatures in some regions can rise above 86 °F (30 °C).

Loading the player...Thinning arctic sea ice

The Arctic is a dry region. Most of the Arctic receives only 2 to 10 inches (5 to 25 centimeters) of precipitation each year, much of which falls as snow. Some parts of the Arctic are as dry as many deserts in other regions.

Land regions.

The Arctic can be divided into three land regions: (1) the polar deserts, (2) the tundra, and (3) the subarctic.

Polar deserts

make up the northernmost lands on Earth. Like warmer deserts, they receive little precipitation and have thin, rocky soil. Strong, cold winds blow frequently in the polar deserts. Few plants can survive the extreme conditions, but lichens—algae and fungi that live together—grow on the rocky surfaces (see Lichen).

The tundra

lies south of the polar deserts. The tundra receives more precipitation than the polar deserts and is therefore more favorable for plant growth. In addition to mosses and lichens, grasses and other flowering plants grow in the tundra. Shrubs also grow there, but trees cannot survive in the tundra. See Tundra.

The subarctic

includes lands south of the 50 °F (10 °C) July isotherm and thus is excluded from some definitions of the Arctic. The subarctic climate is warmer and less dry than that of the tundra and so can support trees. The subarctic includes the northern fringes of the taiga.

Environment and natural resources

The Arctic includes vast areas of wilderness largely untouched by industry and development. Other areas have long served as an important source of food and raw materials.

Soil conditions

in the Arctic are shaped by the presence of permafrost, a layer of permanently frozen soil beneath the ground. Only the top layer of soil, called the active layer, thaws during summer. In some areas, the active layer can extend about 10 feet (300 centimeters) deep. In other areas, it may only thaw to a depth of 8 to 12 inches (20 to 30 centimeters).

Despite the dry climate, Arctic soils tend to be moist because the permafrost prevents drainage. But plants grow slowly because cold temperatures slow biological processes in the soil, limiting the availability of nutrients.

Plant life

in the Arctic is limited by the cold and the short growing season. In the polar deserts, mosses and lichens dominate. The tundra supports a variety of grasses and such shrubs as dwarf birch, Labrador tea, lingonberry, and willow. In the subarctic, birch, larch, and spruce trees may dominate the landscape.

Arctic plants have adapted to the harsh climate and soil conditions in several ways. Some plants have extensive root systems. They use the extra roots to better absorb scarce nutrients from the soil. Because the growing season in the Arctic is only 6 to 12 weeks long, most Arctic plants are perennials—that is, they take several years to complete their life cycle. Some plants can keep their delicate leaves and flower buds alive under the cover of winter snow. When the snow melts, these structures quickly develop to take full advantage of the short growing season. Some Arctic plants can even sprout from seeds under the snow.

Animal life

in the Arctic depends on cycles of plant life for food. In general, food for animals is abundant in the summer and scarce in the winter. During the growing season, such herbivores (plant-eating animals) as lemmings, hares, and caribou flourish. The large population of herbivores in the summer, in turn, supports such predators as snowy owls, Arctic foxes, and wolves.

Both herbivores and predators respond to the changing availability of food in a variety of ways. Some Arctic animals simply leave during the winter. Arctic birds migrate in large numbers to warmer regions in the south. Caribou migrate overland from the tundra to the taiga, where more plants grow during the winter. Some groups of caribou travel more than 3,000 miles (4,800 kilometers) in their migrations.

Other animals survive the winter by living off fat they build up during the summer. Musk oxen restrict their activity in the winter to conserve energy. Their thick, warm undercoats help insulate against the cold. Such predators as foxes, lynxes, and wolves also grow thick fur coats in the winter. Smaller hunters, such as weasels, spend their time under the snow, which reduces their exposure to the cold winds above. They also hunt for lemmings, voles, and other prey beneath the snow. Ground squirrels and bears move into underground dens during the winter and enter a sleeplike state.

Many of the world’s most important fishing waters lie around the edge of the Arctic. Indigenous people also hunt seals and whales in Arctic waters.

Minerals, oil, and natural gas

are abundant in the Arctic, and mining ranks as an important industrial activity throughout the region. Coal deposits are found in Alaska, Siberia, Canada, and Greenland, as well as on Svalbard, a group of Norwegian islands. Subarctic areas of Alaska and Canada support large mining operations for such minerals as copper, gold, lead, silver, and zinc. Several areas in the Canadian Arctic have active diamond mines. The Arctic has large reserves of oil and natural gas, most of them in Russia. Production of oil and gas forms a major part of the economy of Alaska, Norway, and Russia.

Arctic peoples

In the past, indigenous Arctic peoples lived in small, widely scattered groups. The peoples were often isolated from one another and spoke many different languages. Development and modern technology have lessened the isolation of Arctic life for many groups.

Groups.

Siberia is home to a large number of indigenous groups. More than 20 separate groups live scattered along northern Siberia’s coastline and rivers. They speak many languages, most of which are from the Uralic and Altaic language family. Several of their languages are not related to any language family.

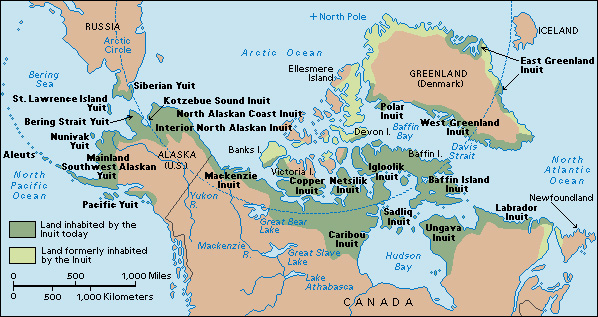

The Arctic coastlines of Alaska, Canada, and Greenland are inhabited by several groups of Inuit and Yuit. They speak languages from the Eskimo-Aleut family. Some American Indian groups also live in the North American Arctic. They speak languages from the Athabascan family.

The Sami people live in Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Kola Peninsula in northwest Russia. They speak several dialects of the Sami language, which is related to Finnish and Estonian.

Traditional ways of life.

Before modernization, most Arctic peoples were hunter-gatherers—that is, they survived by hunting animals and gathering plant materials from the wild. They were seminomadic, moving from place to place to find food. Their diet consisted of fish, game, roots, and berries. Before firearms, Arctic peoples used a variety of devices to hunt, such as snares, traps, harpoons, spears, and bows and arrows. In the winter, they rode sleds pulled by dogs or reindeer.

In winter, many Arctic peoples lived together in small communities. They built underground winter houses made of stone or sod. In summer, smaller bands moved about in search of game. Each band consisted of an extended family—parents, married children and their offspring, and other relatives. Portable tents made of animal skin served as summer housing.

Most Arctic clothing was made of caribou or reindeer fur. The hollow hairs acted as a good insulation against the cold air. People sewed the skins together using sinew and bone needles before thread and steel needles were available. For decoration, they sewed various skins together in decorative patterns. Later, they added trade beads and colored threads to their outfits.

The beliefs of indigenous Arctic people held that animals had spirits that must be respected. Most communities had shamans, men or women who were responsible for communicating with the spirit world.

Arctic exploration

The first written account of the Arctic comes from Pytheas, a Greek who sailed to the Far North around 325 B.C. The Inuit first settled much of the Arctic about 1,000 years ago, around the same time that a Scandinavian people called the Vikings began to explore there. About A.D. 982, the Viking explorer Erik the Red reached Greenland, where he made the earliest known European contact with the Inuit. Erik and other Vikings established colonies in Greenland. However, the colonies did not survive past the 1400’s.

Search for the Northwest Passage.

In 1497, King Henry VII of England dispatched the Italian explorer John Cabot to northeastern North America. Cabot hoped to find a quick passage to eastern Asia by sailing west through North America—a “Northwest Passage.” At the time, Europeans did not realize the size of the North American continent and the extent to which it blocked their path. Though Cabot believed he had reached Asia, in actuality he probably landed in Newfoundland.

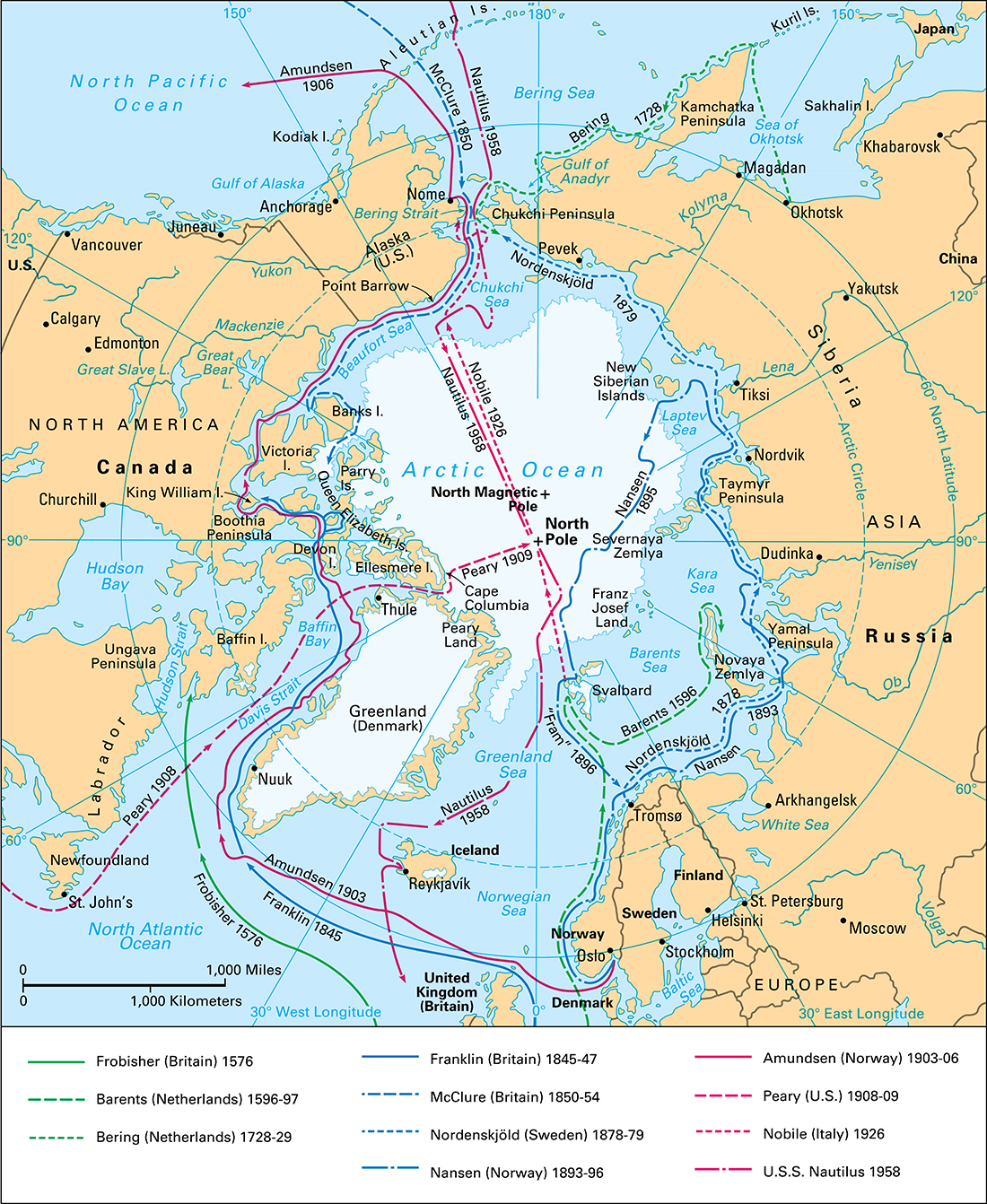

Europeans continued to explore the Arctic. In the 1570’s, the English navigator Martin Frobisher sailed around Greenland to Baffin Island, where he had several hostile meetings with the Inuit. In 1590, the Dutch explorer Willem Barents reached the far northern islands of Svalbard and Novaya Zemlya, which later became whaling centers. In the early 1600’s, the English explorer Henry Hudson sailed farther north than any European explorer before him. He helped to establish the North American fur trade.

In 1648, the Russian explorer Semyon Dezhnev sailed through what is now known as the Bering Strait. Vitus Bering, the Danish navigator for whom the strait is named, made several voyages between 1725 and 1742, exploring the strait and southeastern Alaska. He encountered the Aleuts when he landed on the Shumagin Islands. In 1778, the British navigator James Cook explored North America’s northwestern coast, continuing the search for the Northwest Passage. He passed through the Bering Strait and on to Cape Prince of Wales.

In the early 1800’s, the British Navy sent several expeditions to try to find the Northwest Passage, despite centuries of exploration without success. William Edward Parry, a British naval officer, led three expeditions and went farther north than any previous explorer.

In 1845, the British Navy launched the most ambitious—and ultimately the most disastrous—Northwest Passage expedition. Its leader was John Franklin, who had previously led two Arctic expeditions. In 1847, Franklin’s ships became icebound, and he and his crew died of starvation. Search parties charted much of the remaining stretches of Arctic coast while looking for his stranded expedition. The first explorer to actually sail through the Northwest Passage was the Norwegian adventurer Roald Amundsen in 1906.

Race to the pole.

During the 1860’s, attention turned to reaching the North Pole. To get there, explorers had to cross the treacherous, frozen Arctic Ocean.

After numerous attempts, the American explorer Robert E. Peary claimed to be the first person to reach the pole in 1909. That same week, the American physician Frederick A. Cook claimed that he had reached the pole a year before Peary, in 1908. Peary disputed Cook’s claim, and the controversy over who actually first reached the pole continues today.

The Arctic today

The Arctic, once protected by its remoteness and harsh climate, faces many challenges today. Modernization has upset traditional Arctic ways of life, and many indigenous peoples have struggled to preserve their culture. Further, a warming climate threatens the landscape and environment of the region.

Modernization.

Today, the Arctic is governed by Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Greenland, Russia, and the United States. These countries have worked to develop the region, largely for its natural resources. As a result, the lifestyles of most indigenous peoples have changed dramatically. Many Arctic people speak English or another European language instead of their native language, and many Arctic languages are in danger of being forgotten. Many Arctic peoples have converted from their traditional religions to Christianity.

Most indigenous peoples have settled towns and cities and use modern technology. Many live in prefabricated housing, housing built in sections at a factory and assembled at the building site. Arctic hunters drive snowmobiles and four-wheeled all-terrain vehicles. The modern Arctic diet includes fewer traditional foods and more imported goods, such as frozen meals, soft drinks, and candy.

The removal of minerals, natural gas, and petroleum from Arctic lands has damaged hunting and fishing in many areas. Rapid modernization has also led to serious social problems among indigenous people, such as alcoholism, drug use, domestic violence, and suicide.

Climate change.

The Arctic climate has warmed significantly in the past few decades, causing the ranges of various Arctic plants to shift northward. Shrubs have become dominant in some areas of the tundra, crowding out mosses and lichens. Along with plants, a number of animals have extended their ranges northward. Warming has also changed the life cycle of certain animals. An example is the spruce bark beetle, which attacks spruce trees. The beetle, which once took two years to complete its life cycle in Arctic areas, now completes it in a single year in some parts of the Arctic.

The warming climate results in less of the Arctic Ocean freezing each year. Less sea ice may benefit human activities, such as shipping and pumping petroleum from the sea floor. But many animals depend on the sea ice. Seals and walruses climb onto the ice to rest. Polar bears, who hunt on the ice, are especially threatened by its rapid disappearance.

Loading the player...Disappearing sea ice

The warming climate may also harm human settlement in the Arctic. Warmer air causes more frequent storms, which endanger coastal settlements. The thawing of permafrost can cause roads and buildings to buckle and collapse.

In 2007, scientists from dozens of nations launched a study of the Arctic and Antarctic called the International Polar Year 2007-2008. The investigation involved more than 200 research projects, with a focus on how climate change affects the polar regions and their inhabitants.