Arctic Ocean is the body of icy water covering Earth’s northernmost regions. It ranks as the smallest of the world’s oceans, touching only the northern shores of Asia, Europe, and North America. The North Pole lies near the center of the Arctic Ocean.

People define the boundaries of the Arctic Ocean differently for different purposes. For oceanographers, the ocean’s limits include: (1) the Bering Strait, between Alaska and Siberia; (2) the northern limits of the Canadian islands; (3) Fram Strait, between Greenland and Svalbard; and (4) the opening to the Barents Sea, between Svalbard and Norway. Defined this way, the Arctic Ocean covers about 3,680,000 square miles (9,530,000 square kilometers). Its widest part, between Alaska and Norway, measures about 2,630 miles (4,230 kilometers) across. The narrowest stretch separates Greenland and the Taymyr Peninsula of Russia. These areas lie about 1,200 miles (1,930 kilometers) apart.

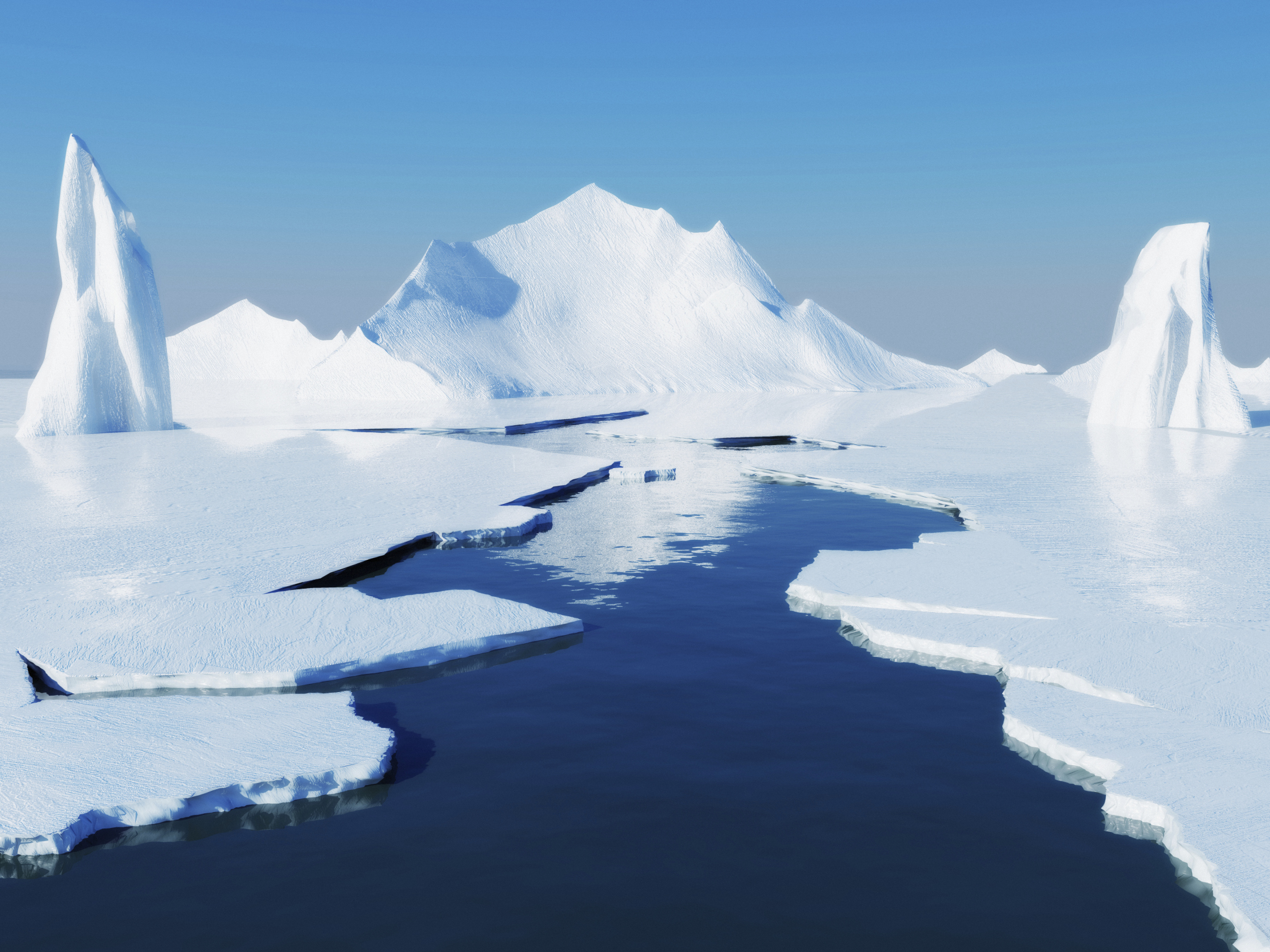

The Arctic Ocean is bitterly cold. At its surface, thick chunks of floating ice form a treacherous, shifting landscape. During the winter, the sun does not rise for weeks over the Arctic Ocean. In the summer, the sun remains above the horizon for several weeks, and some of the ice melts.

The Greek explorer Pytheas sailed near the Arctic Ocean in the late 300’s B.C. He reported that a frozen sea lay a six-day voyage north of Britain. The name Arctic comes from Arktos (bear), the ancient Greek name for a constellation that appears in the northern sky.

Groups of islands divide the coastal waters of the Arctic Ocean into seven seas. These seas, from Greenland eastward, are (1) the Barents Sea; (2) the Kara Sea; (3) the Laptev Sea; (4) the East Siberian Sea; (5) the Chukchi Sea; (6) the Beaufort Sea; and (7) the Lincoln Sea.

Far northern lands extend into the Arctic Ocean. They include most of Greenland and parts of Norway, Russia, and Canada, as well as Alaska. For more information on the land and people of the Arctic region, see Arctic.

Climate

In January, surface water temperatures in the Arctic Ocean drop to as low as about 28 °F (–2 °C), the freezing point of seawater. In summer, the waters warm to only a few degrees above freezing—and only in limited areas.

A high-pressure dome of cold, dry air generally covers the Arctic region. It prevents moist, warmer air from the south from reaching the central Arctic Ocean. As a result, rain and snowfall tend to be light over the Arctic Ocean. However, fog commonly forms over coastal waters in the summer, when humid, warm air from the land blows out over the ocean.

Arctic weather varies dramatically. In winter, violent storms form rapidly and unexpectedly in some areas. Such storms are sometimes called Arctic hurricanes.

Since the late 1900’s, the patterns of air pressure that drive Arctic weather have been changing. The changes result from a combination of natural cycles and global warming. Global warming is an average increase in Earth’s surface temperature, thought to be caused in part by human activities (see Global warming). Scientists have linked changing air pressure patterns to other changes, such as increases in the frequency of storms and the strength of waves. These changes, in turn, contribute to increased erosion along lengthy stretches of Arctic coastline.

Ice

Much of the Arctic Ocean is covered in a thick layer of floating ice. Most of the ice is sea ice or frozen seawater. The rest is glacial ice, which breaks off from glaciers along the coasts of Arctic lands.

Sea ice.

Seawater freezes at a lower temperature than does fresh water because seawater has a higher salt content. When sea ice forms on the ocean surface, much of the salt sinks into the water below.

In winter, the cover of sea ice spreads beyond the Arctic Ocean’s boundaries. But in the summer, the sea ice melts to less than half the ocean’s area. The ice that remains in the Arctic Ocean throughout the summer can be up to 15 feet (5 meters) thick. The ice sometimes piles up into ridges and becomes thicker.

Arctic sea ice is constantly on the move. Winds and currents push the floating ice at speeds of up to about a mile or a couple kilometers per day. On the North American side of the ocean, the ice tends to drift in a clockwise motion called the Beaufort Gyre. On the European side, it flows along a path from the New Siberian Islands toward Fram Strait, called the Transpolar Drift.

Because sea ice is always moving, there are always areas of open water throughout the ice cover, called leads. Leads range from extremely thin cracks to huge breaks in the ice as wide as rivers.

Some areas of the ice cover tend to have thin ice or open water in the same place each winter. These areas, called polynias, serve as seasonal homes to many living things in the Arctic Ocean.

Glacial ice,

unlike sea ice, is frozen fresh water from glaciers on land. Chunks of glacial ice break off along the coasts of Greenland, northern Canada, Svalbard, and other lands to form icebergs. Some icebergs become part of the Arctic sea ice cover. Many other icebergs float into the North Atlantic Ocean, where they eventually melt in the warm waters of the Gulf Stream.

Icebergs can be extremely dangerous to ships. Some icebergs are so large and thick that they are called ice islands. Scientists have even been able to set up research stations on some ice islands.

Disappearance of ice.

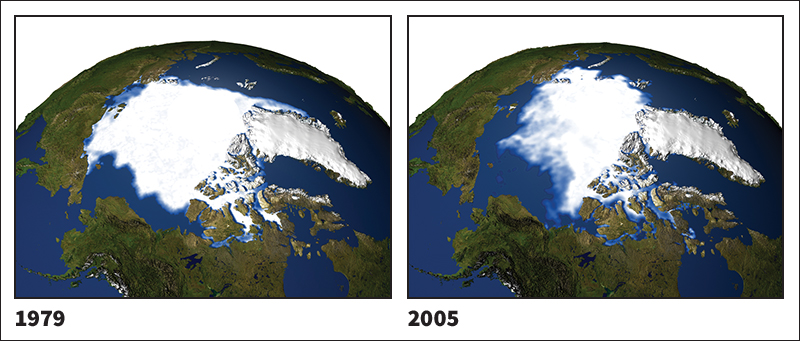

The Arctic Ocean’s summer sea ice cover has decreased by about 10 percent each decade since 1978, when satellite measurements were first gathered. Global warming may be contributing to this trend in a number of ways. For example, more sea ice may melt each year as a result of warming air temperatures over Siberia and North America. The ice cover may also be affected by changing weather and ocean circulation patterns related to global warming.

Declining sea ice cover could accelerate warming across the planet. White snow and ice reflect the sun’s heat back into space, in much the same way that white clothing helps people stay cool in the summer sun. Darker areas of open water, on the other hand, absorb the sun’s heat in much the same way dark clothing does. Thus, the more the ice melts, the more heat Earth absorbs. The heat can, in turn, cause even more ice to melt, creating a dangerous, escalating cycle.

Ocean life

Despite its icy cover, the Arctic Ocean supports a diversity of wildlife. Seals and whales feed on fish and tiny floating organisms called plankton. Large numbers of diatoms, a type of plantlike phytoplankton, thrive near the surface of waters along the edges of the sea ice. Some whales eat huge amounts of shrimplike zooplankton called krill.

Shellfish serve as an important source of food for walruses, bearded seals, and sperm whales. Halibut and other bottom-dwelling fish are plentiful in shallow seas along the ocean’s coasts.

Polar bears live on top of the sea ice. They use it as a platform from which to hunt seals in the water below.

The ocean floor

The floor of the Arctic Ocean includes a shallow area along the coasts—called the continental shelf—and a central area called the deep basin. The Arctic Ocean’s average depth is 4,465 feet (1,361 meters).

The continental shelf

is a gently sloping band of underwater land at the edges of the continents. In the Arctic Ocean, it is mostly less than 500 feet (150 meters) deep. North of Greenland and North America, it extends about 45 to 120 miles (70 to 200 kilometers) from shore. Off the Russian coast, it extends much farther into the ocean—up to 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) from shore.

The deep basin.

Several underwater ridges crisscross the deep basin of the Arctic Ocean. These ridges divide the deep basin into several smaller basins.

The Lomonosov Ridge, the tallest of the dividing ridges, rises about 10,000 feet (3,000 meters) from the surrounding floor. It extends about 1,100 miles (1,800 kilometers), stretching from a point near Ellesmere Island to an area north of the New Siberian Islands. The Lomonosov Ridge divides the deep basin into two main areas—the Canadian Basin and the Eurasian Basin. The Canadian Basin has an average depth of 12,500 feet (3,800 meters). The Eurasian Basin has an average depth of 13,800 feet (4,200 meters).

Several other ridges run parallel to the Lomonosov Ridge. On the Canadian side, the Alpha Ridge and the Mendeleyev Ridge form a ridge system that stretches from north of Ellesmere Island to the East Siberian Sea. The ridge system separates the Canadian Basin into two smaller parts—the Canada Basin and the Makarov Basin.

In the European Basin, the Nansen-Gakkel Ridge stretches from the tip of Greenland toward the Laptev Sea. It separates the Amundsen Basin from the Nansen Basin. The Amundsen Basin includes the deepest areas of the Arctic Ocean, dropping in places to more than 18,000 feet (5,500 meters) below the ocean surface.

Waters

Water constantly flows into, out of, and around the Arctic Ocean, pushed along by currents and winds. In addition, about 10 percent of Earth’s river water flows into the Arctic Ocean.

Currents.

The North Atlantic Current brings a large amount of relatively warm, salty water from the Atlantic Ocean into the Arctic Ocean. The rest of the seawater flowing into the Arctic Ocean comes from the Pacific Ocean. This water is colder and less salty.

Ice and water flow out of the Arctic Ocean through the Fram Strait and along the East Greenland Current. Some of this water flows all the way around Greenland into Baffin Bay. There, it circles in a counterclockwise motion before flowing south. It is joined by water flowing out of the Arctic Ocean through passages between Canadian islands, where it forms the Labrador Current of the northwestern Atlantic Ocean.

Water masses.

The Arctic Ocean’s waters are not uniform in temperature or salt content. As in other oceans, the different layers of the water form distinct water masses with unique properties.

The Arctic Ocean’s surface waters tend to be less salty than those of other oceans. Rivers and precipitation bring much fresh water to the ocean’s surface. Also, the formation of sea ice causes much salt to sink to lower levels. The surface waters circulate in a pattern similar to that of sea ice, following the Beaufort Gyre and the Transpolar Drift. These motions vary somewhat, depending on wind patterns. The surface waters extend down to about 80 to 250 feet (25 to 75 meters) of depth.

Below the surface waters lies a near-freezing, nutrient-rich mass of winter Pacific water. This layer reaches about 500 feet (150 meters) deep and is generally found only in basins in the ocean’s Canadian side.

A warmer mass of Atlantic water lies deeper, reaching 2,625 feet (800 meters) below the surface. This water enters the Arctic Ocean from the Fram Strait, where it starts out several degrees above freezing. It circulates in the smaller basins in counterclockwise patterns.

The deepest water mass, called Arctic bottom water, is saltier and colder than the Atlantic water mass. The Arctic bottom water is slightly warmer and saltier in the Canadian Basin than in it is in the Eurasian Basin. Little is known about how the Arctic bottom water circulates.

Tides.

The Arctic Ocean has smaller tides overall than the other oceans do, probably due to its small size and nearly landlocked geography. Most of the tides in the Arctic Ocean rise and fall less than 1 foot (0.3 meter).

The Arctic Ocean and people

The Arctic Ocean has long provided fishing waters and hunting platforms for Arctic peoples. For many centuries, Europeans tried to find a sea route through the Arctic Ocean, referred to as the Northwest Passage. The Arctic Ocean continues to provide many natural resources. But it also faces threats from pollution and global warming.

Use.

The Arctic Ocean provides a water route to distant Arctic ports. It enables ships to deliver fuel, manufactured goods, and other products to Arctic settlements and carry back such goods as fish, fur, and lumber. Special icebreaker ships clear routes for these ships, and aircraft help guide them through the ice.

Major petroleum deposits lie off the north coast of Russia and Alaska, and oil wells operate in these areas. The continental shelf near Canada and Russia is also believed to hold large reserves of oil and natural gas.

Russian and Nordic fishing crews catch such fish as cod and halibut in the Barents and Kara seas. Arctic people of several nations hunt whales in the Arctic Ocean.

Threats.

Pollution is limited in the Arctic Ocean because there is little development in the region. However, the disposal of wastes from military bases in the Arctic has resulted in some local pollution, as has oil production on the Alaskan shelf. Air pollution sometimes drifts over the region from factories in China, Russia, the United States, and other northern countries. This pollution contributes to the Arctic haze sometimes reported by airplane pilots.

Some toxic chemicals used in low latitudes end up in the Arctic because they repeatedly evaporate, redepositing in colder areas. These chemicals tend to accumulate in animal fat, reaching higher concentrations in animals high on the food chain.

Global warming causes the Arctic Ocean’s sea ice to decrease. The ice’s disappearance threatens polar bears and other animals that depend on it.