Hurricane is a powerful, swirling storm that begins over a warm sea. Hurricanes then move westward and often toward the poles. When a hurricane hits land, it can cause great damage through fierce winds, torrential rain, flooding, and huge waves crashing ashore.

Loading the player...

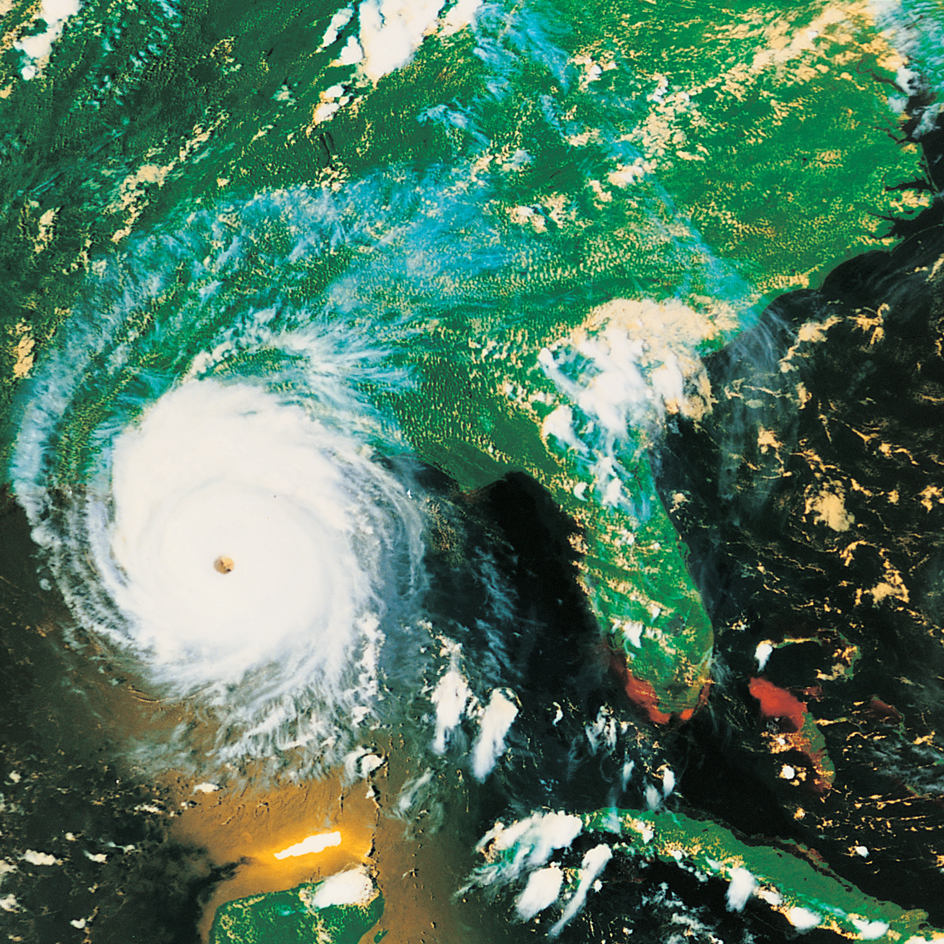

Hurricane Carla in 1961

Loading the player...

Hurricane winds

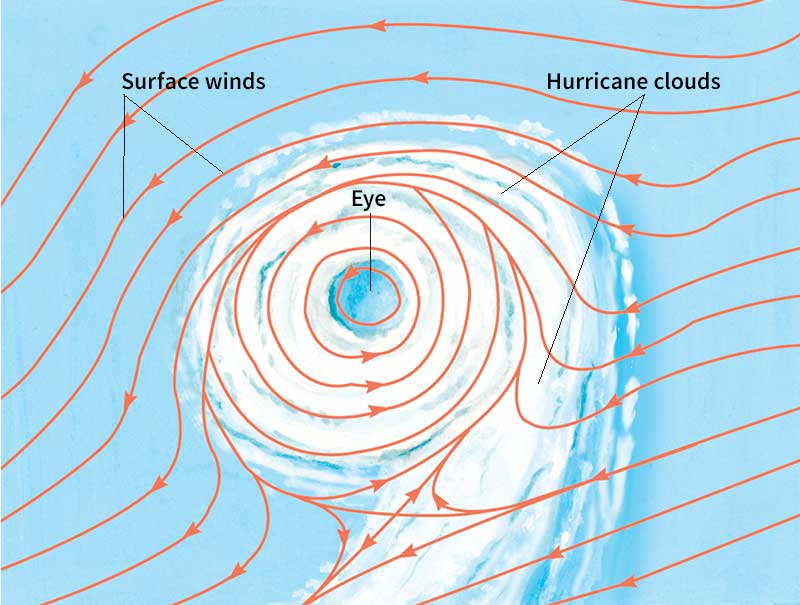

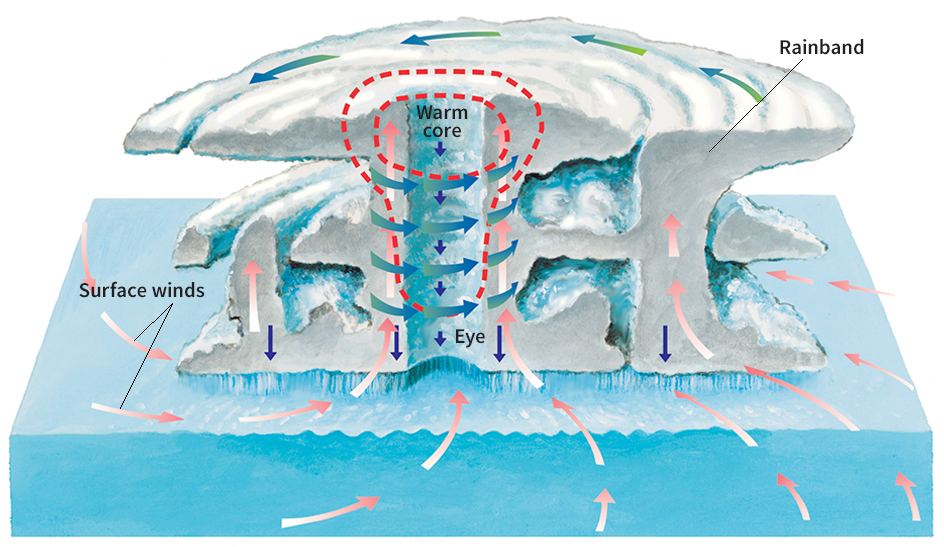

The winds of a hurricane swirl around a calm central zone called the eye. The eye usually measures 10 to 40 miles (16 to 64 kilometers) in diameter and is usually free of rain and large clouds. A band of tall clouds called the eyewall surrounds the eye. The strongest winds occur in and under the eyewall. These winds can reach nearly 200 miles (320 kilometers) per hour. Damaging winds may extend 250 miles (400 kilometers) from the eye.

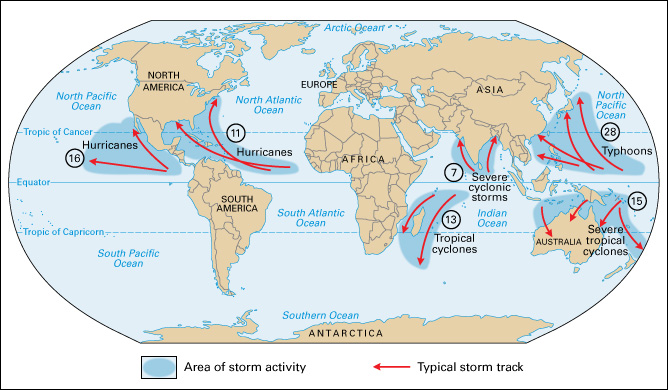

The term hurricane is actually one of several regional names used to describe a type of storm known as a tropical cyclone. A sufficiently strong tropical cyclone is called a hurricane when it happens over the North Atlantic Ocean, the Caribbean Sea, the Gulf of Mexico, or the Northeast Pacific Ocean. Such tropical cyclones are known as typhoons if they occur in the Northwest Pacific Ocean, west of an imaginary line called the International Date Line. In the Southwest Pacific and Southeast Indian oceans, they are called severe tropical cyclones. In the North Indian Ocean, they are known as severe cyclonic storms. In the Southwest Indian Ocean, such storms are referred to simply as tropical cyclones.

Hurricanes are most common during the summer and early fall. In the Atlantic and the Northeast Pacific, for example, August and September are the peak hurricane months. Typhoons occur throughout the year in the Northwest Pacific but are most frequent in summer. In the North Indian Ocean, severe cyclonic storms strike most often in May and November. In the South Indian Ocean, the South Pacific Ocean, and off the coast of Australia, the tropical cyclone season runs from December to March. Approximately 90 hurricanes and other tropical cyclones occur in a year throughout the world. In the rest of this article, the term hurricane refers to all such storms.

How a hurricane forms

Hurricanes require a special set of conditions, including ample heat and moisture, that exist primarily over warm tropical oceans. For a hurricane to form, there must be a sufficiently warm layer of water at the top of the sea. This warm seawater evaporates into the air. The moisture then condenses (changes into liquid), forming clouds. As the moisture condenses, it releases heat that warms the air, causing it to rise. The warm, rising air creates a region of relatively low atmospheric pressure. Atmospheric pressure is the weight of the air pressing down on a given area.

Air tends to move from areas of high atmospheric pressure to areas of low pressure, creating wind. Earth’s rotation can cause the wind to swirl as it blows into a low-pressure area. In the Northern Hemisphere, these winds swirl in a counterclockwise direction. In the Southern Hemisphere, winds rotate clockwise. This effect of the rotating Earth on wind flow is called the Coriolis effect. The Coriolis effect increases in intensity farther from the equator. To produce the swirling winds of a hurricane, a low-pressure area must be more than 5 degrees of latitude north or south of the equator. Hurricanes seldom occur closer to the equator.

As the swirling winds increase in speed, more ocean water evaporates and then condenses. The moisture releases more heat, further warming the storm’s core. The warm air rises faster, increasing surface wind speeds, and so on. This cycle, called a positive feedback loop, continues to strengthen the hurricane. When friction between the air and the water surface becomes great enough, the hurricane stops intensifying.

For a hurricane to develop, there must be little wind shear—that is, little difference in speed and direction between winds at upper and lower elevations. Uniform winds enable the warm inner core of the storm to stay intact. The storm would break up if the winds at higher elevations increased markedly in speed, changed direction, or both. The wind shear would disrupt the budding hurricane by tipping it over or by bringing dry air into the center of the storm.

The life of a hurricane

Meteorologists (scientists who study weather) divide the life of a hurricane into four stages: (1) tropical disturbance, (2) tropical depression, (3) tropical storm, and (4) hurricane.

Tropical disturbance

is an area where rain clouds are building. The clouds form when moist air rises and becomes cooler. Cool air cannot hold as much water vapor as warm air can, and the excess water changes into tiny droplets of water that form clouds. The clouds in a tropical disturbance may rise to great heights, forming the towering thunderclouds that meteorologists call cumulonimbus clouds.

Cumulonimbus clouds usually produce heavy rains that end after an hour or two, and the weather clears rapidly. If conditions are right for a hurricane, however, there is so much heat energy and moisture in the atmosphere that new cumulonimbus clouds continually form from rising moist air.

Tropical depression

is a low-pressure area surrounded by winds that have begun to blow in a circular pattern. A meteorologist considers a depression to exist when there is low pressure over a large enough area to be plotted on a weather map. On a map of surface pressure, such a depression appears as one or two circular isobars (lines of equal pressure) over a tropical ocean. The low pressure near the ocean creates wind, which evaporates seawater and so feeds more thunderclouds.

The winds swirl slowly around the low-pressure area at first. As the pressure becomes even lower, the winds blow faster, and more ocean water evaporates.

Tropical storm.

When the winds exceed 38 miles (61 kilometers) per hour, a tropical storm has developed. Viewed from above, the storm clouds now have a well-defined circular shape. The seas have become so rough that ships must steer clear of the area. The strong winds near the surface of the ocean draw more and more heat and water vapor from the sea. The increased warmth and moisture in the air feed the storm.

A tropical storm has a column of warm air near its center. The warmer this column becomes, the more the pressure at the surface falls. The falling pressure, in turn, creates more wind, which evaporates more ocean water and leads to even warmer air in the column.

Each tropical storm receives a name. The names help meteorologists and disaster planners avoid confusion and quickly convey information about the behavior of a storm. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO), an agency of the United Nations, issues four alphabetical lists of names, one for the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, and one each for the Eastern, Central, and Northwestern Pacific. The lists include both men’s and women’s names that are popular in countries affected by the storms.

Storms in the South Pacific and much of the Indian Ocean are named by the regional weather center located closest to the forming storm. These centers are found in Australia, India, Indonesia, New Zealand, and Papua New Guinea. The centers use a naming method similar to that of the WMO. Storms in the Southwestern Indian Ocean are named by the many African countries affected by such storms along with France. Each of the participating countries contributes at least one name to a given year’s list.

Except in the Northwestern and Central Pacific, the first storm of the year gets a name beginning with A—such as Tropical Storm Alberto. If the storm intensifies into a hurricane, it becomes Hurricane Alberto. The second storm gets a name beginning with B, and so on through the alphabet. The lists do not use all the letters of the alphabet, however, since there are few names beginning with such letters as Q or U. For example, no Atlantic or Caribbean storms receive names beginning with Q, U, X, Y, or Z.

Because storms in the Northwestern Pacific occur throughout the year, the names run through the entire alphabet instead of starting over each year. The first typhoon of the year might be Typhoon Nona, for example. The Central Pacific usually has fewer than five named storms each year.

The system of naming storms has changed since 1950. Before that year, there was no formal system. Storms commonly received women’s names and names of saints of both genders. From 1950 to 1952, storms were given names from the United States military alphabet—Able, Baker, Charlie, and so on. The WMO began to use only the names of women in 1953. In 1979, the WMO began to use men’s names as well.

Hurricane.

A storm achieves the status of hurricane—or the equivalent name used in another region—when its winds exceed 74 miles (119 kilometers) per hour. By the time a storm reaches hurricane intensity, it usually has a well-developed eye at its center. Surface pressure drops to its lowest in the eye.

In the eyewall, warm air spirals upward, creating the hurricane’s strongest winds. Heavy rains fall from the eyewall and from bands of dense clouds that swirl around the eyewall. These bands, called rainbands, can produce more than 2 inches (5 centimeters) of rain per hour. The hurricane draws large amounts of heat and moisture from the sea.

The path of a hurricane

Hurricanes last an average of 3 to 14 days. A long-lived storm may wander 3,000 to 4,000 miles (4,800 to 6,400 kilometers), typically moving over the sea at speeds of 10 to 20 miles (16 to 32 kilometers) per hour.

Hurricanes in the Northern Hemisphere usually begin by traveling from east to west. As the storms approach the coast of North America or Asia, however, they shift to a more northerly direction. Most hurricanes turn gradually northwest, north, and finally northeast. In the Southern Hemisphere, the storms may travel westward at first and then turn southwest, south, and finally southeast. The path of an individual storm is irregular and often difficult to predict.

All hurricanes eventually move toward higher latitudes where there is colder ocean water, less moisture, and greater wind shear. These conditions cause the storm to weaken and die out. The end comes quickly if a hurricane moves over land, because it no longer receives heat energy and moisture from warm tropical water. Heavy rains may continue, however, even after the winds have diminished.

Hurricane damage

Hurricane damage results from wind and water. Hurricane winds can uproot trees and tear the roofs off houses. The fierce winds also create danger from flying debris. Heavy rains may cause flooding and mudslides.

The most dangerous effect of a hurricane, however, is a rapid rise in sea level called a storm surge. A storm surge occurs when winds drive ocean waters ashore. Storm surges are dangerous because many coastal areas are densely populated and lie only a few feet or meters above sea level. A 1970 cyclone in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) caused a surge that killed from 300,000 to 500,000 people. A hurricane in Galveston, Texas, in 1900, produced a surge that killed about 6,000 people, the worst natural disaster in U.S. history.

Great Hurricane of 1938

Hurricane watchers rate the intensity of a storm on a scale called the Saffir-Simpson scale. The scale was developed by the engineer Herbert S. Saffir and the meteorologist Robert H. Simpson, both of the United States. The scale designates five levels of hurricanes, ranging from Category 1, described as weak, to Category 5, which can be devastating. Individual hurricanes change category as they grow or diminish in intensity. Hurricanes that have reached Category 5 include Hurricane Camille, which hit the United States in 1969; Hurricane Gilbert, which raked the Caribbean Islands and Mexico in 1988; Hurricane Andrew, which struck the Bahamas, Florida, and Louisiana in 1992; and Hurricane Katrina, which caused widespread destruction in parts of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama in 2005. In 2012, Hurricane Sandy, a Category 1, caused unprecedented damage and flooding from South Carolina to Maine.

Forecasting hurricanes

Meteorologists use weather balloons, satellites, and radar to watch for areas of rapidly falling pressure that may become hurricanes. Specially equipped airplanes called hurricane hunters investigate budding storms.

If conditions are right for a hurricane, the National Weather Service of the United States issues a hurricane watch. A hurricane watch advises an area that there is a good possibility of a hurricane within 36 hours. If a hurricane watch is issued for your location, check the radio or television often for official bulletins. A hurricane warning means that an area is in danger of being struck by a hurricane in 24 hours or less. Keep your radio tuned to a news station after a hurricane warning. If local authorities recommend evacuation, move quickly to a safe area or a designated hurricane shelter.