Ice skating is the act of gliding over a smooth surface of ice on ice skates—boots with attached metal blades. For hundreds of years, people could ice skate only during the winter months in cold climates. They skated on natural ice surfaces, such as frozen canals, lakes, ponds, and rivers. Today, machines produce ice in indoor rinks, making ice skating a form of recreation that can be enjoyed throughout the year.

People of almost any age can enjoy ice skating as healthful and relaxing exercise. Skaters use most of the body’s muscles, especially the leg muscles. Skating helps blood circulation by strengthening the heart.

Ice skating is an important competitive sport as well as a popular form of recreation. Athletes compete in two kinds of ice skating—figure skating and speed skating. Figure skaters perform leaps, spins, and other graceful movements, usually to music. Speed skaters compete in races of various distances. Many young people and adults also play hockey, a fast, rugged sport in which the players wear ice skates. Millions of people attend ice shows each year. Ice shows are colorful spectacles that often feature champion figure skaters.

This article describes safety rules for recreational skaters. It then discusses figure skating and speed skating as competitive sports. For information on hockey, see Hockey.

Skating safety

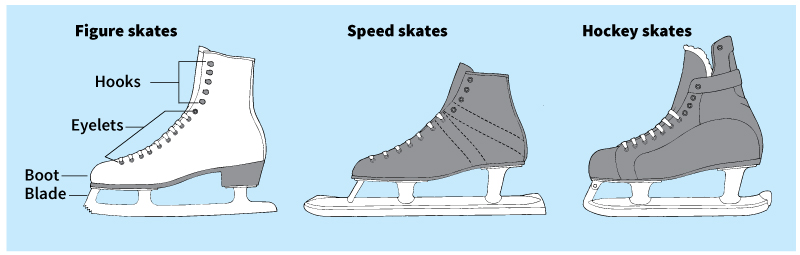

Use of the right equipment is essential to skating safety. The boots should fit properly—that is, they should be snug but not too tight. The blades should be attached securely to the boots and correctly positioned to distribute the weight of the body evenly over the blades. Figure skaters, speed skaters, and hockey players use different types of skates. Many beginning skaters use figure skates. The boot has a high top for good ankle support. In addition, the design of the blade enables beginners to maneuver more easily than they could on speed or hockey blades.

Before going onto the ice, you should lace your boots properly, whether you are a beginning or experienced skater. Proper lacing provides needed support for the ankles. Lace each boot as tightly as possible in front of the ankle. Never skate, or even walk, in unlaced boots. Unlaced boots can result in a fall and a serious injury.

Skating on a natural ice surface can be more dangerous than skating on an indoor rink or on an artificially created outdoor rink. The great danger is the risk of falling through thin ice. Therefore, never skate on a natural ice surface that is less than 4 inches (10 centimeters) thick. And never skate alone on natural ice. Always make sure a ladder and a rope are available for rescue purposes. To rescue a skater who has fallen through the ice, lie on the ladder as close as possible to the hole. The ladder spreads your weight evenly over the ice and prevents you from falling through. Use the rope to pull the skater to safety. You may also use the rope as a lifeline. Tie one end to a tree or to someone on shore and tie the other end around your waist before attempting a rescue.

Rinks generally attract more skaters than do natural ice sites, which increases the chance of collisions. For this reason, rinks forbid fast skating at public sessions and require all skaters to move in the same direction.

Figure skating

Figure skating competitions are held on a rink about 200 feet (60 meters) long and 100 feet (30 meters) wide. The rink has gently rounded corners and is surrounded by a barrier about 4 feet (1.2 meters) high.

Figure skates have a special blade that enables competitors to perform the difficult moves required in figure skating. The blade is about 1/4 inch (6 millimeters) thick, depending on the size of the boot, and about 12 inches (30 centimeters) long. The blade has an inside and an outside edge. Skaters skate on one edge at a time. The bottom of the blade is slightly curved inward. This curve permits only a small part of the blade to touch the ice at one time, enabling a skater to maneuver more easily. The front of the blade has several teeth called toe picks. Skaters use the toe picks to bite into the ice when performing certain jumps and spins. The boots of figure skates have a high top.

Figure skaters wear costumes that are comfortable and attractive and that permit freedom of movement. Women generally wear a simple dress with a short skirt and matching tights. The men usually wear close-fitting, comfortable pants with a matching shirt.

Loading the player...Dick Button at the 1948 Winter Olympics

Figure skaters may take part in (1) singles skating, (2) pair skating, (3) ice dancing, and (4) synchronized skating. Men and women compete separately in singles skating, but they follow similar rules. In pair skating and ice dancing, teams consisting of a man and a woman compete against one another. Synchronized skating involves groups of 8 to about 20 skaters who compete as teams. They perform as a single unit rather than as soloists.

Figure skaters compete at various levels, depending on their skill. Skaters must pass proficiency tests to advance to a higher level. The highest is the senior level.

In the United States, skaters are given two sets of marks by judges, one for technique and one for presentation. Judges use a scale of 0 to 6 points, with 6 being the highest score. They carry the skaters’ scores to one decimal place, as in a score of 3.7. The International Skating Union (ISU), which governs the sport worldwide, has adopted a judging system based on cumulative points. Under this system, points are awarded for how accurately the skater executes, combined with points awarded for five additional presentation and artistic elements. The United States will phase in the ISU judging system in future seasons.

Singles skating

consists of two parts in both men’s and women’s competition. They are the short program and the free skating program, also known as the long program.

The short program

counts as one-third of the skater’s total score for the competition. It consists of a certain number of required moves or elements: jumps, spins, and fast step sequences or footwork. All skaters perform the same moves or elements. The moves may be done in any sequence with a 2-minute 50-second time limit. The moves are performed to music selected by the skater.

Each skater receives two scores. The first score reflects the required elements of the skater’s program—that is, how accurately the skater performed the moves. The second score reflects the program’s artistic impression, which evaluates the overall program, including its choreography, artistry, and expression.

The free-skating program

accounts for two-thirds of the skater’s score. Free skating has no required elements and has a length limitation of 4 minutes for women and 41/2 minutes for men. In free skating, the skaters select their own music and theme, and choreograph many difficult spins, jumps, footwork, and interpretive moves to best display their technical and artistic skills. As in the short program, scores are given for technical merit and for presentation.

Pairs skating.

In pairs skating events, the couples try to express a feeling of harmony and teamwork through their skating. Pairs skating involves certain moves specifically designed for a man and woman skating together. The most spectacular moves are lifts, in which the man picks up his partner and carries her above his head. Pairs skaters perform most moves in unison. They may separate at times and perform individually, but the two must maintain the impression that they are performing as a true team. Like single skating, competition in pair skating consists of the short program and the free-skating program.

The short program

counts one-third of each pair’s score. The program calls for eight moves that all the pairs must perform. However, each couple may arrange the moves and the steps that link them in any order and pattern. The pairs select their own music. The program must be completed within 2 minutes and 50 seconds.

The judges score each couple on required elements and presentation. They base the artistic impression score on such factors as creativity, how well the pair expressed a sense of unity, and how smoothly their steps linked the various moves.

The free-skating program

makes up two-thirds of each pair’s score. The couples select their own moves and their own music. Each pair’s program may last up to 41/2 minutes. As in the short program, the judges give scores for technical merit and presentation. In scoring presentation, they rate each pair’s program on composition and style. They also consider how well the couple express a feeling of “togetherness.”

Ice dancing

combines skating with ballroom dancing. It differs from pairs skating in several ways. In ice dancing, for example, the couple may separate only briefly to change direction or position. No high lifts are permitted. Each partner must have one skate on the ice at all times except during brief lifts and spins when the woman may have both skates off the ice. The couples perform many moves developed specifically for ice dancing. These moves closely resemble steps used in ballroom dancing.

Ice dancing competition consists of three parts. They are, in the order performed: (1) compulsory dances, (2) the original dance, and (3) free dancing.

Compulsory dances

count 20 percent of the score in ice dancing. All the couples perform one dance to the same music. A typical group of compulsory ice dances would be based on the waltz, the rumba, and the tango. Skaters must perform the dances according to official diagrams.

The original dance

makes up 30 percent of a couple’s score. The partners select their own steps and music, but all couples must choose music that follows a certain dance rhythm announced in advance. The dance must be composed of repetitive sequences consisting of either one half circuit or one complete circuit of the ice surface. It must be skated two times around the surface.

Couples receive scores for composition and presentation. Presentation includes how well a couple expressed the music’s theme and tempo.

The free dance

accounts for 50 percent of the score. The couples select their own combinations of dance movements but may not repeat combinations. They also choose their own music, which must have variations in tempo and be suitable for dancing. Each couple must complete their program within four minutes.

The judges grade each couple’s program on technical merit and artistic impression. Artistic impression involves the composition of the dance and how well the partners interpreted the music and its theme.

Synchronized skating

stresses formations and maneuvers performed in unison by teams of skaters. Like ice dancing, synchronized skating permits the use of vocal music. The teams are judged on the composition, presentation, and originality of their routines, as well as their footwork and speed. A senior program can last up to 41/2 minutes.

Speed skating

Speed skating consists of races over various distances on oval, ice-covered tracks. Some skaters reach a speed of 35 miles (56 kilometers) per hour.

The blade and boot of speed skates are so designed that skaters can start quickly and maintain a high rate of speed throughout a race. The blade is flat, straight, and thin. It measures 14 to 18 inches (36 to 45 centimeters) long and only about 1/32 inch (0.8 millimeter) wide. Steel tubing reinforces the blade. The boots are lightweight and have a low-cut top.

In the mid-1990’s, many speed skaters began using a “clapskate,” in which the blade is hinged to the boot’s toe. The clapskate design permits the skater to get maximum propulsion by keeping the blade continuously in contact with the ice throughout each stride. A traditional speed skate leaves the ice as part of the skating motion. Skaters using the clapskate set many records, and the design has revolutionized the sport.

Speed skaters wear gloves or mittens and a one-piece uniform with long sleeves. The uniform is made of lightweight synthetic fabric designed to offer little wind resistance.

Good speed skating technique depends on three factors: (1) balance, (2) rhythm, and (3) drive. These factors enable a skater to produce smooth, powerful strokes. Technique, strength, and speed are also important.

A speed skater’s center of balance is in the hip over the center of the forward skate that is pushing. As the legs move back and forth, the center of balance shifts from the outside of the blade to the center of the blade and onto the returning skate. Skaters keep the body relaxed and flexible. They lean forward from the waist with the back straight. They keep the head up and the eyes looking straight ahead.

A smooth, flowing motion produces the proper skating rhythm. The rhythm’s most obvious part is the arm swing. Skaters swing one arm forward and the other to the rear. The forward arm is always opposite the forward leg. The swing keeps the skater’s balance steady and helps raise the forward stroke’s power.

The drive is the push from the legs on each stroke. Speed skaters use the blade’s entire surface to push forward. They try to bend their knees as much as possible to increase the stroke’s length. The longer the stroke, the more powerful will be the forward push. Skaters swing one arm forward and the other arm to the rear when competing in 500- and 1,000-meter sprint races. The forward arm is always opposite the forward leg. The arm swing keeps the skater’s balance steady and helps increase the power of the forward stroke.

In races up to 1,000 meters long, skaters swing their arms on each stroke. In races 1,500 meters long, some skaters save energy and wind resistance by swinging one arm and keeping the other on their back. In races 1,500 meters and longer, most save energy by clasping both hands behind their back as they skate on the oval track’s straight parts. They use the right arm swing as a counterbalance only while skating around turns.

There are three types of speed skating: (1) long-track, or Olympic-style, skating, (2) pack skating, and (3) short-track skating. Men and women compete separately.

Long-track skating

is the most recognizable type of racing internationally. Two skaters race each other on a two-lane track 3331/3 to 400 meters (364 .5 to 437 yards) around. Each lane should be about 5 meters (16 feet) wide. A band of snow or colored markers divides the lanes.

Most men’s international competitions are 500, 1,000, 1,500, 5,000, and 10,000 meters long. Women’s races cover 500, 1,000, 1,500, 3,000, and 5,000 meters.

Skaters start a race either side-by-side or staggered, depending on the distance of the race. The skater starting in the inner lane wears a white armband. The skater starting in the outer lane wears a red armband. When the starter orders “go to the start,” both skaters move to the area between the pre-starting line and the starting line. The lines are about 30 inches (75 centimeters) apart. At the word “ready,” both skaters assume their starting positions, holding them until the starter fires a gun. Each skater is allowed one warning for a false start. A second false start means disqualification.

Skaters compete in several heats called pairs. Winning the pairs does not necessarily mean winning the event. Skaters race against the clock. Their times are converted into points, and the skater with the lowest point total wins the event.

Pairs and lane assignments are determined by a drawing before the event. Names are drawn two at a time from a pool of seeded (ranked) skaters, forming a pair. The fastest skaters receive the highest seeds. Skaters prefer to skate in the fastest pair possible to improve their chances for a fast time.

During the race, the speed skaters must change lanes each time they reach the crossing straight. This is the straight-away area on the track opposite the starting line. The only times skaters do not change lanes are on the first laps of 1,000-meter and 1,500-meter races run on a 400-meter track. Competitors change lanes so that each skater races the same distance because the inside lane covers a shorter distance than the outside lane.

A skater has completed the distance when he or she has touched or reached the finish line with the tip of the skate as recorded by an electronic eye beam. The winner for each race is the skater with the lowest time, measured to a one-hundredth of a second, after all the skaters have raced. If two skaters tie, they are judged as tied. No tie breakers are allowed.

Skaters who fall during a race are allowed to get up and continue. For distances less than 5,000 meters or 10,000 meters, however, it is generally impossible to make up lost time.

In most meets, skaters enter all the races. In sprint championships, they skate 500 meters and 1,000 meters on the first day, and repeat the same races on the second day. After all the competitors have raced, the one with the fastest overall time in the four events wins. The samlog scoring system converts times skated into points. Each second in the 500 equals 1 point, and each second in the 1,000 equals one-half of a point.

In the all-round championships, starters race short and long distances. Men skate 500, 1,500, 5,000, and 10,000 meters. Women skate 500, 1,500, 3,000, and 5,000 meters. The samlog scoring system for the longer distances gives one-third of a point for each second for 1,500 meters, one-sixth of a point for 3,000 meters, one-tenth of a point for 5,000 meters, and one-twentieth of a point for 10,000 meters. The skater with the lowest point score wins. In world all-around championships, only the top 16 finishers after three races qualify for the fourth and longest race.

Pack skating

has a number of competitors race at one time in a series of elimination races. Qualifiers then advance to final races.

Pack-style skating meets are held on both indoor and outdoor tracks. Most outdoor tracks measure 400 meters around. There are indoor facilities that house 400-meter ovals. Skaters also use a hockey rink for indoor competition.

In organized meets, men and women and boys and girls compete separately in age classes. These classes are senior (age 18 and older); intermediate (ages 16 and 17); junior (ages 14 and 15); juvenile (ages 12 and 13); midget (ages 10 and 11); pony (ages 8 and 9); and tiny tot (ages 5 and younger). There are also master age groups for skaters from 30 to 70 years old. Skaters may compete in older age classes but not in a younger one, except in the master divisions.

The length of the races in a pack-style skating meet depends on the age class. The youngest skaters take part in the shortest races. For example, boys and girls in the midget class compete in races up to 800 meters long on 400-meter tracks and up to 1,000 meters long on indoor rinks. Senior men compete in races up to 3,000 meters long. Each contestant in an age group must enter all the races. The number of races depends on the divisions and the type of competition.

At a meet, the skaters in each class first compete in a series of qualifying races called heats. From 4 to 6 skaters race at one time in a heat. In most meets, the skaters who finish first and second—and sometimes third—in each heat qualify for the next heat. The number of heats depends on how many skaters entered the event. In most meets, each final race has a maximum of six skaters.

Skaters receive points in each final race. An international point system is used. The winner receives 34 points with the 8th place skater receiving 1 point. The skater with the most points is the class champion.

Short-track skating

consists of two types of races: (1) individual races and (2) relay races. Men and women compete separately. This kind of racing is called short track because the races are held on an oval track 111.12 meters (364.57 feet) around, the size of a hockey rink used in international competition. The track must be at least 4.75 meters (151/2 feet) wide on the straightaways and at least 4 meters (13 feet) wide on the turns. It has no lanes.

Competitors normally skate in a series of heats or elimination rounds for the individual events. Heats include up to six skaters, with the top two finishers from each heat advancing to the next round.

Each skater is allowed one false start and is disqualified after the second. The start is crucial to the skater, especially in the shorter races, because the start is not staggered and a skater can move to the inside immediately. During the race, skaters must skate outside the rubber or plastic blocks that mark the shape of the track. However, a finger can skim the surface of the ice inside the blocks as long as the skater rounds the blocks.

Skaters must pass cleanly and without body contact. Passing is tricky. Skaters take advantage of key areas to pass. If the lead skater strays too far from track markers, an alert competitor can pass him or her on the inside. If the track is skated tightly by the pack, passing must be done on the outside.

Passing rules are strict. One infraction will disqualify a skater. The lead skater has the right of way and the passing skater must assume responsibility for avoiding body contact. A skater can be disqualified for intentionally pushing, obstructing, or colliding with another racer. Improperly crossing the course, also called cross-tracking, is prohibited, as is kicking the skate across the finish line. A bell warns skaters when they are one lap from the finish of the race.

Falls are common in short-track racing because of the frequent contact between skaters. Although a skater is not disqualified for a fall, to win a race after a fall is nearly impossible. Skaters may still do well in the final classification of the competition by recording strong finishes in other individual events.

Individual races.

In international championship meets, individual skaters compete in two short events (500 and 1,000 meters), a middle distance race (1,500 meters), and a long race (3,000 meters).

Skaters must qualify in heats to compete in the final race. No more than four skaters can race at one time in the short races. No more than six can race in the 1,500-meter race at one time. No more than eight can race in the 3,000-meter race at one time. The skater who finishes first in the final wins the event.

Relay races involve four teams, each with four members. Men race in a 5,000-meter relay, and women in a 3,000-meter relay. One member from each team skates until replaced by a teammate. A teammate may replace a skater anytime except during the final two laps. Skaters may not begin to race until they touch, or are touched by, the teammate they replace. The team of the first skater to reach the finish line wins the race.

History

The earliest evidence of ice skating was found among Roman ruins in London and dates back to 50 B.C. Excavations of the ruins uncovered leather soles and blades made of polished animal bones. About A.D. 1100, people in Scandinavia wore skates made of deer or elk bones, which were strapped to their boots with leather. These early skates were used for transportation. Recreational ice skating may have begun during the 1100’s in Britain.

Iron blades were first used in the Netherlands about 1250. Steel blades on wooden soles apparently were first used about 1400. These skates were lighter than iron skates and made skating easier.

In 1850, E. W. Bushnell of Philadelphia produced the first all-steel skates. These skates were light and strong, and kept their sharp edges longer than iron skates. All-steel skates greatly increased the popularity of skating. Skating clubs opened across the country. About 1870, a young American ballet dancer named Jackson Haines became the first person to blend creative dance movements with ice skating. He is credited with introducing modern figure skating into Europe.

In 1892, the International Skating Union was founded. That year, the first international speed skating and figure skating competitions were held in Vienna, Austria. Figure skating was included in the 1908 Olympic Games, and speed skating became an Olympic event in 1924. Only men competed in Olympic speed skating until 1960, when women’s competition began. Ice dancing became an Olympic event in 1976. Men’s and women’s short-track skating was added for the 1992 Winter Games.

The first figure skater to become internationally famous was Sonja Henie of Norway. Henie was the women’s Olympic figure skating champion in 1928, 1932, and 1936. Henie then appeared in several American movies that featured her skating. Other Olympic women’s champions who became professional skating stars included Barbara Ann Scott of Canada, Peggy Fleming and Dorothy Hamill of the United States, and Katarina Witt of East Germany.

Dick Button of the United States was the leading men’s figure skater of the mid-1900’s, winning the Olympic championship in 1948 and 1952. Other modern men’s Olympic and professional skating stars included John Curry and Robin Cousins of the United Kingdom, Toller Cranston of Canada, and Scott Hamilton of the United States. In the 1980 Olympics, Eric Heiden of the United States became the first athlete to win all five of the speed skating races. He set a record in each race. Bonnie Blair of the United States won five speed skating gold medals in the Olympics from 1988 to 1994. The star of the men’s speed skating competition at the 1994 Olympics was Johann Olav Koss. He won three races, all in record time. The Netherlands dominated speed skating in the 1998 and 2002 Olympics.