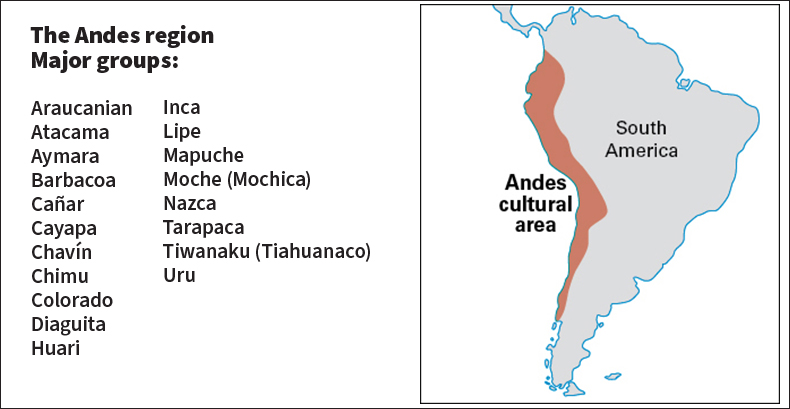

Inca were an Indigenous (native) South American people who ruled one of the largest and richest empires in the Americas. The Inca empire emerged in the early A.D. 1400’s and occupied a vast region centered around the capital of Cusco, in southern Peru. The empire extended over 2,500 miles (4,020 kilometers) along the western coast and mountains of South America. It included parts of present-day Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina. The Inca empire was conquered by Spanish forces in 1532.

Inca emperors expanded their far-reaching territory in a variety of ways. They took over many areas by military force but more often expanded their rule by creating alliances or through the threat of force. Local leaders who cooperated with the Inca were often allowed to stay in power. The name Inca was originally the name of the group that formed the royal court and was the title used for the emperor himself. The peoples he ruled had many names, but after the Spanish conquest, some people started calling all South Americans who were once under the emperor’s rule Inca.

The Inca were skilled engineers and craftworkers. They built a network of roads linking the distant provinces of the empire, and their architecture is renowned for its immense scale and skillful construction. Inca craftworkers created fine items from gold, silver, and other materials, and wove fine cotton and woolen cloth.

Way of life

Archaeological remains provide the main source of information about Inca civilization. The Inca themselves recorded their history in songs and stories. Written records of the Inca from the period after Spanish conquest provide additional information on Inca civilization.

Food, clothing, and shelter.

The Inca used several methods to make their farms more productive. They built irrigation canals in the coastal desert. In the highlands, they cut terraces into the hillsides to reduce erosion and level the land for irrigation. They planted their fields by hand using simple tools. The Inca divided fields in lands they conquered into three groups that were all worked by their subjects. The harvest of one set of fields went to the local people. The other two sets of fields were harvested for the Inca state and temples.

The main crops of the Inca were corn, cotton, potatoes, a root crop called oca, and a grain called quinoa. Freeze-dried potatoes called chuno were made in the highlands to preserve the harvest for long-term storage. The Inca brewed chicha, a beer made from corn. Important domesticated animals were the llama, alpaca, and cuy (guinea pig). Llamas and alpacas provided meat, often dried to make a durable food called charqui, and wool for clothing. Llamas also were used to transport goods over long distances.

Clothing was made of wool or cotton, and the nobles wore the finest weaves. Inca men wore loincloths and, in cold weather, tunics and cloaks. Their clothes were decorated with symbols of their rank. Women wore long cloths draped around their bodies and square shawls, called mantas, around their shoulders. Their clothing was fastened with tupu, which were long pins with round, flat heads of silver and bronze.

On the coast, most houses were built with cane walls and roof. In the highlands, houses of adobe or stone set in mud with a thatched roof were common. Usually, several houses were grouped within a walled courtyard. Nobles in Cusco lived in palaces built of fine stone. Palaces and temples had large rectangular halls called kallanka, where people slept, dined, or worshiped.

Family and social life

among the Inca varied with social rank. Inca society was composed of social classes including commoners; a servant class called yanacona; local nobles or kuraka; and the royal court of Cusco. Within social classes, people were organized in groups called ayllu, based on both kinship and common land ownership. Sometimes the Inca would move whole villages from their home regions to other parts of the empire to provide a service to the state. These services might include working state lands or settling uninhabited areas.

Inca men and women married into their own classes. Noblemen could have more than one wife. Commoners married within their ayllu, and husbands and wives worked together in the fields and at other tasks. Women were the primary organizers of the household. The Inca separated children into age classes, with each group defined by the children’s abilities to contribute to the work effort of the family and the state. Children began working for the family before the age of 6. Individuals were considered adults only when they married and performed labor as full members of the community.

Religion

was important in the public and private lives of the Inca. The Inca believed that the world was created by a god they called Viracocha. The ruling family claimed descent from the sun, Inti. The earth goddess, Pachamama, was one of the most important female gods, and the sea and the moon were also worshiped as goddesses. These gods spoke to people through oracles (prophets) and expressed their anger by sending natural disasters, such as earthquakes and droughts, to punish those who displeased them.

The Inca regarded many places and objects as huaca (sacred). Mummies of important ancestors, temples, and historical places were all worshiped as huaca. Natural features on the landscape, such as springs, boulders, caves, and mountain peaks, were also sacred and called apu. Each household also had one or more small statues, or illa, that were sacred to the family.

The Inca believed that the will of their gods and spirits could be understood through divination, the study of magic signs. The Inca would divine whether a certain day was good for activities, such as planting crops or going to war. The mummies of the dead Inca kings were maintained by their descendants in the palaces they lived in during life. On occasion, the mummies were brought to Cusco to be consulted by the emperor.

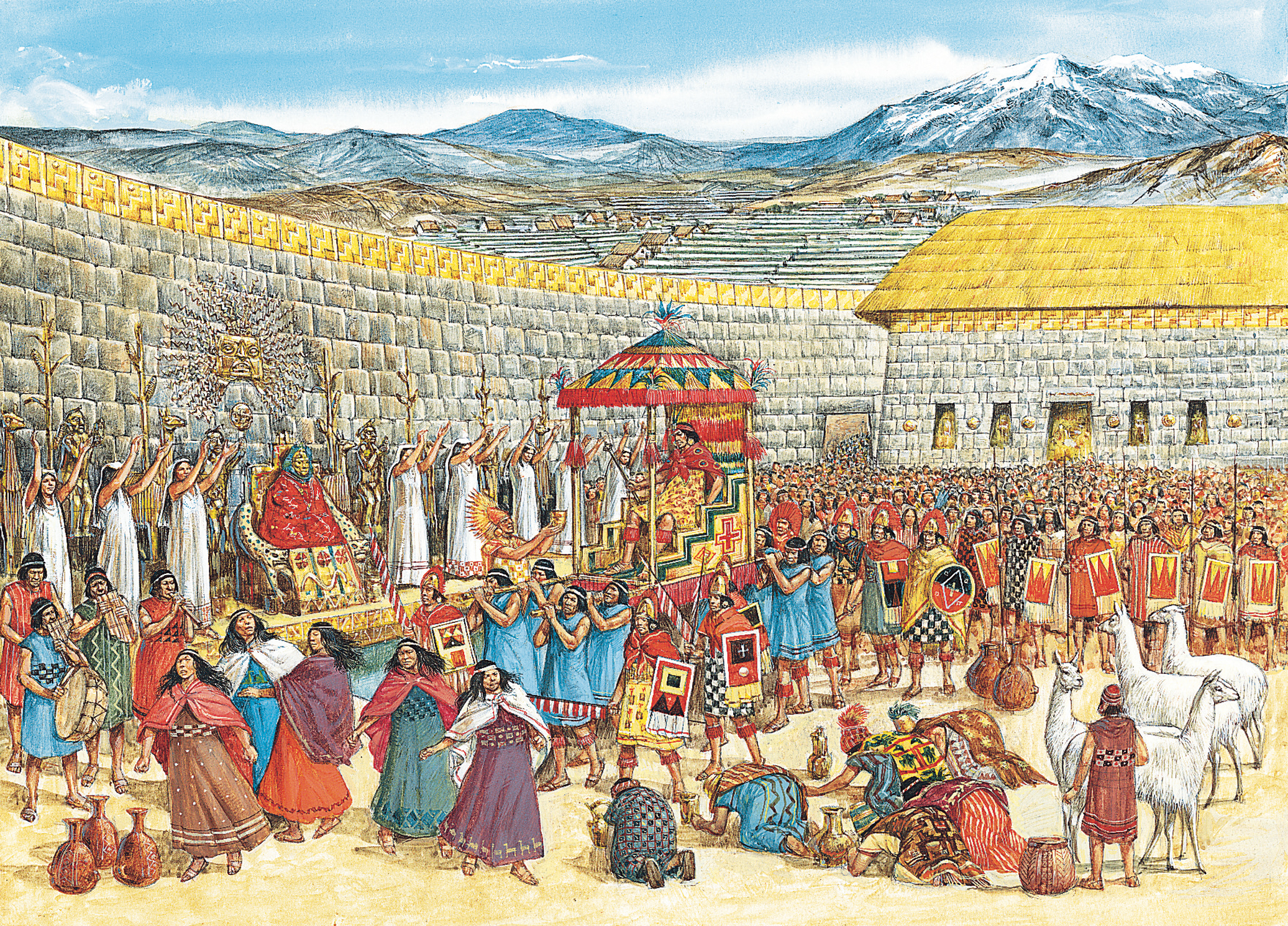

Religious ceremonies marked important calendar events as well as events in the life of a ruler. One of the annual events was Inti Raymi, which was held on the June solstice, when the sun is at its most northerly point. Inti Raymi is still celebrated in Cusco today. Capac Raymi, held during the December solstice, when the sun is at its most southerly point, was perhaps the most important annual celebration. Both of these events included dancing, feasts, games, songs, and parades.

Sacrifices and offerings were important in all Inca religious ceremonies, especially at the death of the emperor. The Inca sacrificed crops and animals, mainly llamas, to ensure adequate rainfall and keep the earth fertile. Human sacrifices were made under special circumstances. For example, young children would travel from various parts of the empire to take part in the capac ucha (royal obligation). These children were blessed by the emperor and then returned to their home province to be sacrificed. Most people considered it a great honor to be chosen for sacrifice.

Priests were important in Inca society. The most powerful priests were often close relatives of the royal family. Priests made offerings, performed sacrifices, and maintained the temples. Aclla (chosen women) prepared sacred foods to be used in religious ceremonies and wove the cloth worn by the rulers and priests.

Priests treated the sick in curing ceremonies and used herbs and other plants as medicine. Surgeons operated on the skull to release evil spirits or relieve pressure on the brain caused by injury. This operation, called trephining, was often successful in treating wounds that would otherwise have caused death. See Trephining.

The Inca believed in three worlds: an underworld of the ancestors, a celestial world of the gods, and an earthly world where people live. The Inca believed that beings in the other worlds could affect their lives in the living world. Important people were buried in stone chambers above ground. Others were buried in pits, caves, or other kinds of graves.

Trade and transportation.

The Inca economy did not operate with money. Instead, the Inca state produced fine pottery, cloth, items of precious stones, and metalwork in silver, gold, and bronze that were used as gifts to keep the loyalty of local lords. The state also stockpiled food, weapons, and other goods to support the army and other workers. Inca subjects performed a labor tax, called mita, to make the food and supplies the Inca needed. The Inca’s subjects also exchanged crafts, food, and other goods among themselves.

A well-constructed network of roads connected all parts of the Inca empire. Suspension bridges maintained by the local communities spanned rivers and canyons. Some of these roads and bridges still exist today. Rest stops were common along the roads. Some of these were large structures with facilities to house the Inca army and storehouses to feed travelers.

People traveled by foot, and they and llamas carried all loads. The Inca did not use any wheeled carts or vehicles, which were useless on the mountainous roads. The emperor and nobles rode on litters, seats mounted on poles and carried on men’s shoulders. The Inca used boats and rafts on the major rivers, lakes, and on ocean voyages along the Pacific coast.

Government.

Members of a ruling family governed the Inca empire. The emperor, called the Sapa Inca, traditionally married his sister, known as the coya. However, the Inca called many female relatives sister, so the coya may have been a close female relative other than an actual sister. The coya was the emperor’s main wife.

A council of nobles who ruled the provinces of the empire aided the empire. The empire was organized into four parts, each of which had several provinces and was led by a principal governor. Within the provinces, the Inca designated lesser lords.

All subjects of the empire paid labor tax by doing work for the government. Women were required to weave cloth. Men had to work on construction projects, including canals, roads, or bridges; toil in the mines; or serve in the army. People had to work the ruling family’s farmland in addition to their own. Inspectors made sure that local lords and their subjects complied with the labor tax.

Communication and learning.

The Inca spoke a language called Quechua. Different peoples within the empire spoke a variety of other Indigenous languages. A second important language in the empire was Aymara. Both Quechua and Aymara are still spoken by millions of people in the Andes today.

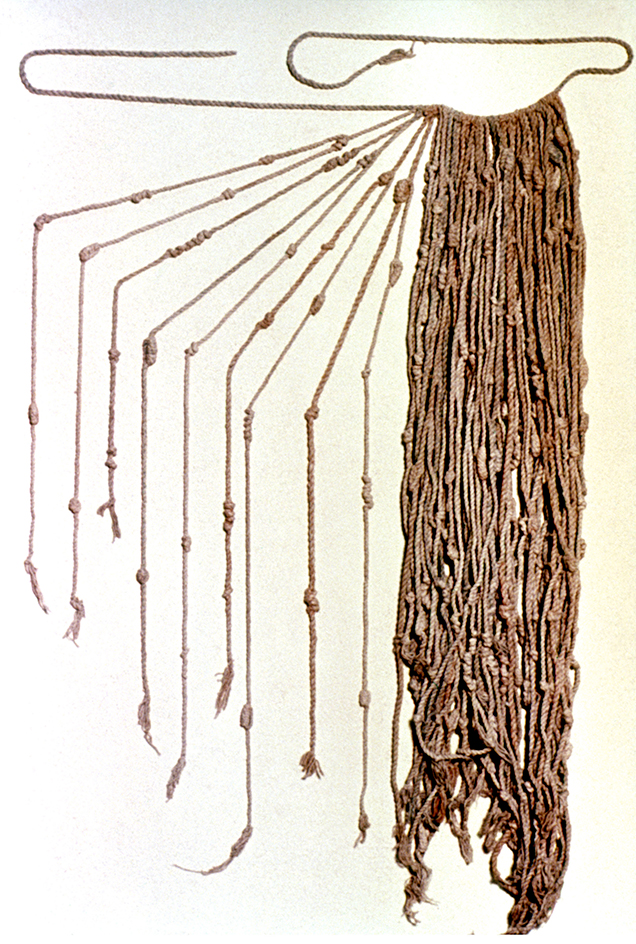

The Inca did not have an alphabet. They did have quipu, a cord with knotted strings of various lengths, colors, weaves, and designs that served as a system of recordkeeping. Special officials throughout the empire could read the quipu and maintained the knotted strings. Most people in the Inca empire could not read them. Archaeologists have discovered how the Inca recorded numbers and dates using quipu. However, they are still trying to understand what other information might be encoded in the knotted strings.

Information was passed through the empire on the system of royal roads by the messengers, called chaski. Messages were passed by word of mouth or by quipu. Chaski were stationed every few miles, and messages would be passed from one messenger to the next so information would flow quickly throughout the empire.

The sons of local rulers were sent to Cusco, where they were instructed in the Inca language, history, and religion. They were also taught about the quipu and Inca fighting techniques by teachers called amauta. These teachers recorded stories and legends in poems and song that they retold at gatherings so the people would remember their history.

Arts and architecture.

The Inca produced fine metalwork in gold, silver, and bronze and wove fine textiles of wool and cotton. Pottery was painted with geometric designs in black, brown, red, white, and yellow. Ceramics and textiles of the nobles incorporated designs, called tocapu, that had symbolic meaning for the Inca rulers. Musical instruments included woodwinds and drums. Flutes and panpipes made of wood, ceramics, and bone played the haunting melodies of the Andes.

Inca builders were known for their sturdy temples and palaces made of stone. Large blocks of rock were cut so finely that they fit together without cement. The architecture of Cusco, its fortress at Sacsayhuamán, and Machu Picchu, a royal retreat north of Cusco, are good examples of the Inca building style.

History

Early days.

Before the rise of the Inca empire, the land around Cusco was a province of the Wari empire, formed about A.D. 600. The collapse of the Wari empire about 1000 created opportunities for various local rulers to gain power. Inca myths tell of the emergence of four brothers and their sisters from a cave south of Cusco. For many years, they wandered the land, with some of the brothers and sisters dying or turning to stone. The last remaining pair, Manco Capac and Mama Ocllo, founded the city of Cusco and displaced the people living there. Their descendants, the Inca, began to expand their rule over neighboring groups through alliance and warfare. By about 1400, they were one of several powerful kingdoms in the region.

The empire.

According to Inca legend, the nearby Chanca kingdom invaded Inca lands. A son of the ruling Inca defeated the invading Chanca after his father fled Cusco. This son took the name Pachacuti, meaning earth shaker, and became the first Inca emperor. He made Cusco the capital and built a large army.

Pachacuti and his son, Topa Inca Yupanqui, extended the Inca empire northwest into central and northern Peru. After Topa Inca Yupanqui became emperor, he expanded the empire into what are now western Bolivia, northwest Argentina, northern Chile, and western Ecuador. Huayna Capac, the son of Topa Inca Yupanqui, later unified the conquered regions of highland Ecuador and southern Colombia.

Huayna Capac died about 1527, and two of his sons, Huascar and Atahualpa, fought to become emperor. Huascar lived in Cusco and was favored by many Cusco nobles. Atahualpa controlled a large army in Ecuador. The civil war ended when Atahualpa captured Huascar in 1532.

The Spanish conquest.

In 1532, the Spanish explorer Francisco Pizarro arrived in Cajamarca, Peru. Pizarro was accompanied by about 180 men, who lured Atahualpa into a trap, captured him, and held him prisoner. Pizarro demanded a ransom of a room filled with gold and another filled twice with silver. The Inca paid the ransom, but the Spanish killed Atahualpa anyway.

While captive, Atahualpa had ordered Huascar to be executed. Therefore, the Inca had no recognized ruler following the execution of Atahualpa. The population was also weakened by diseases, such as smallpox, introduced by the invading Spanish. Thus, the Inca capital fell easily to the Spanish.

The Inca heritage

is still evident in the Andes today. Spanish conquerors tried to destroy the Inca religion and customs, but did not succeed. Many people still speak Quechua, the language of the Inca. Farmers still work on terraces the Inca built, and clothing styles of the Inca have been passed down through the generations.