Income tax is a tax on the earnings of individuals and corporations. Nearly all nations levy income taxes to pay for their government programs. Such taxes may be levied by the federal government, state or provincial governments, and even some local governments.

The United Kingdom was the first country to collect a general income tax. The government passed the tax in 1799 as a temporary measure to help pay the costs of the Napoleonic Wars (1796-1815). Many countries enacted income taxes from time to time during the 1800’s. These taxes were often to help meet unusual expenses, such as wars. The income tax came into wide permanent use during the early 1900’s.

In countries where most people work for wages or salaries—including Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States—the individual income tax raises more money for the government than any other source of revenue (income). In countries where most people are self-employed in agriculture or service industries, such as India and Malaysia, individual income taxes provide a much smaller part of the government’s revenue.

Many people have argued that income taxes have a negative effect on economic activity (buying, selling, and producing goods and services). These people believe that income taxes have become too complicated and question their fairness. Some people have even called for income taxes to be eliminated. But an income tax will likely remain an important part of most countries’ tax systems.

Types of income taxes

The two major kinds of income taxes are individual income taxes and corporate income taxes. Individual income taxes, also called personal income taxes, are levied on the income of individuals. Corporate income taxes are applied to the earnings of corporations.

An income tax may be either progressive or proportional. Under a progressive income tax, a person owes a higher percentage of taxes as he or she earns more taxable income. Taxable income is the amount left over after certain items have been subtracted from total earnings. For example, under a progressive tax, a person with a taxable income of $10,000 may pay a tax of 20 percent of that income, or $2,000. But a person whose taxable income is $20,000 may pay a tax of 25 percent of that income, or $5,000.

Under a proportional income tax, people pay the same percentage of tax for all levels of taxable income. For example, under a proportional tax rate of 20 percent, a person whose taxable income is $10,000 must pay a tax of 20 percent of that income, or $2,000. A person with a taxable income of $20,000 must also pay a tax of 20 percent of his or her income, or $4,000.

Current issues

The fairness and structure of income tax systems are the subject of frequent debate. Many lawmakers favor the use of progressive income taxes because they believe income taxes should be based on a person’s ability to pay. Moreover, they believe that people with large incomes have the ability to pay more taxes as a percentage of income than people with smaller incomes. Debates often arise, however, over the definitions of such terms as taxable income. Other current issues concern the effect of inflation (a continual increase in prices throughout a nation’s economy) on income taxes and the effect of taxes on the economy.

Defining taxable income.

To levy an income tax, a government must define taxable income. Taxpayers are allowed to subtract certain expenses in calculating their taxable income. These expenses are called deductions in Australia, New Zealand, and the United States. In the United Kingdom, such expenses are known as allowances. In many countries, charitable contributions, a percentage of medical expenses, and contributions to private pension funds or certain kinds of savings plans may be deducted from taxable income.

Nearly all countries permit taxpayers to deduct from taxable income some types of expenses necessary to the earning of income. But it is often difficult to determine what is a necessary expense. For example, the cost of a business trip may be a necessary expense and, therefore, a legal deduction. It is not as clear-cut, however, that a taxpayer should be allowed to deduct the cost of a luxurious hotel room if less expensive lodgings were available.

Some political leaders have proposed eliminating most or all deductions and other adjustments to taxable income. When a tax plan with few or no deductions also has a proportional rate structure, it is often called a flat tax. Some people believe that adopting a flat tax would eliminate many unfair deductions and simplify tax returns. Opponents of the flat tax say that it would cause the middle class to pay too much and the rich to pay too little. See Flat tax .

In some countries, serious problems arise over the taxation of capital gains. Capital gains are the profits earned from the sale of stocks, real estate, or other income-producing property. Some people believe low tax rates on capital gains strengthen the economy by encouraging investment. Others believe low rates on this type of profit provide a loophole for wealthy taxpayers—that is, a way for them to avoid paying what some people consider an appropriate share of taxes. See Capital gains tax .

Effects of inflation.

The tax systems of most countries are designed to be progressive—that is, to tax large incomes at a higher rate than small incomes. Many people are concerned about the influence of inflation on progressive income taxes. This concern arises because an increase in people’s income during a period of inflation does not necessarily mean an increase in their wealth. For example, if prices generally rise 10 percent and a worker receives a 10 percent raise, the worker can buy only as much as he or she could buy before the inflation occurred. But under a progressive income tax, such a raise may cause the worker’s income to be taxed in a higher tax bracket (category), even though the worker’s buying power has remained the same. This is known as bracket creep, because inflation pushes people into higher tax brackets.

To solve this problem, governments in some countries adjust their tax rate schedules based on changes in prices for certain items. This is known as indexing the tax system for inflation. This method of adjustment helps keep inflation from causing people to pay more in taxes.

Inflation can also cause other problems in measuring the real return (profit) someone has earned on an investment. For example, if an individual buys a share of stock for $100, holds it for one year, and sells it for $110, the stock’s value has increased by 10 percent. Under the income tax system of many countries, selling the stock would mean that the individual owes tax on the $10 increase in the stock’s value. If prices rose by 10 percent during the year, however, the stock price has merely kept up with inflation. In other words, it is not worth more when it is sold than when it was purchased. In this case, the tax system overestimates how much the individual profited.

The same problem arises when people earn income from interest on their savings and investments. That is because part of the interest earned is only keeping up with inflation. Eliminating bracket creep does not address this problem. Fixing it would require much more complex adjustments.

Income tax complexity.

Many people are concerned that income tax systems have become too complex. Even tax professionals can find it difficult to calculate how much individuals owe. Many people also complain that filing tax returns takes too long, costs too much money, and causes too much stress. Many people find that their financial situation becomes more complicated over time. For example, they may invest in the stock market or start their own business. Such changes force taxpayers to deal with aspects of the tax law that are new to them.

Another cause of complexity is that governments use the tax system to influence people’s behavior in ways that have little to do with raising revenue. For example, tax deductions for charitable contributions are designed to encourage people to donate money to charitable organizations. Requiring people to keep records about their donations makes the tax system more burdensome. Proposals that eliminate all deductions—such as the flat tax—would simplify the tax system. But they would not allow governments to use the tax system to encourage activities deemed worthy of special tax treatment.

Effects on the economy.

Economists (experts who study the production and use of goods and services) disagree about the effect of income taxes on economic activities. Activities that could be affected include personal savings, investment, and work effort. Some economists think income taxes limit economic growth. They argue that an economy needs investment to grow and that income taxes cause people to save less and businesses to invest less. Some experts also claim that progressive income taxes discourage taxpayers from working hard to earn additional income because that income would be heavily taxed. But other economists doubt that income taxes have a large effect on savings, investment decisions, or work effort.

There is no doubt, though, that the income tax has an impact on certain choices that people and businesses make. For example, there is wide agreement that the deduction for charitable contributions encourages people to donate money. Also, when tax rates are about to go up, people do sell stocks and cash in stock options that have increased in value, so that the income will be taxed at the lower rate.

Federal income taxes in the United States

Most individuals and corporations in the United States must pay federal income taxes. Some individuals and businesses do not have to pay income taxes or are taxed at special rates. For example, a person may earn so little money that he or she has no taxable income. Such nonprofit groups as charitable organizations and churches may pay no income tax or be taxed at low rates. Special tax rules are also applied to the income of banks, insurance companies, and some other corporations.

United States income taxes, like those of most countries, are progressive taxes. There are seven federal individual income tax rates ranging from 10 percent to 37 percent of taxable income. The federal corporate income tax rate is a proportional rate of 21 percent. Many people and businesses also pay separate taxes on wages to help finance Social Security programs. These are known as Social Security contributions or payroll taxes. See Social security (Financing Social Security)

Figuring the individual income tax.

To determine income subject to tax, taxpayers first total their wages and salaries, taxable interest, capital gains, and other kinds of income. Some types of income, called exclusions, are not taxable. Exclusions include interest on certain state and municipal bonds, gifts, inheritances, veterans’ benefits, welfare benefits, compensation for sickness or injuries, and certain Social Security payments. Also, employee pension contributions and health care benefits are not counted as taxable income. The taxpayer may also subtract some business expenses and moving costs, and contributions to certain retirement accounts. The result of these calculations is called the adjusted gross income.

Next, the taxpayer claims any deductions. For example, home mortgage interest payments, state and local taxes, charitable contributions, and a percentage of medical expenses may be deducted. For individuals whose calculated total deductions are small, a standard deduction can be taken instead.

Taxpayers may also claim exemptions, set amounts that are subtracted from adjusted gross income. Taxpayers may claim one exemption for themselves, one for their spouse, and one for each of their dependents. The exemptions are reduced or eliminated at higher income levels. Tax credits also may be subtracted from tax due. These credits are designed to provide relief from income tax to special groups of people, such as low-income families.

In general, taxpayers are divided into four categories for filing purposes: (1) single people; (2) married people filing jointly—that is, a married couple who pay one income tax on their combined income; (3) married people filing separately—that is, the husband and wife each pay a separate income tax; and (4) heads of households (single taxpayers who maintain a household for a certain other person or persons). Taxes differ for all four groups.

Some people may have to pay a tax called the alternative minimum tax (AMT) in addition to the regular income tax. The AMT is based on a set of rules for determining the minimum amount of tax that should be paid by a person with a certain level of income. If a person’s regular income tax is less than that amount, the person must pay additional tax to reach the amount. But if the person is already paying that amount or higher in regular income tax, he or she does not have to pay the AMT. The original purpose of the AMT was to prevent people with high incomes from using special tax benefits to pay little or no tax. However, the AMT affects many people who do not have high incomes or special tax benefits.

Paying the individual income tax.

Some individuals, including the self-employed, pay their income tax directly to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). But for those taxpayers who work for a salary or wages, their employers withhold tax from each paycheck and send the money to the IRS. This government agency is responsible for collecting most federal taxes.

Each year, taxpayers fill out a tax return. They state how much taxable income they received during the previous year and how much they have already paid in withholding tax. If, according to the tax rate schedule, they have paid too little tax, they send the additional money to the IRS. If they have overpaid, they receive a refund.

The law requires most people to submit their tax return for the year by April 15 of the next year. Those who owe additional tax money must send their payment by April 15. If they do not do so, they must pay a fine, plus interest on their late payment. Many people send their returns to the IRS by computer.

In addition to their regular tax return, many taxpayers must fill out an estimated tax return for the coming year and send it to the IRS by April 15. Taxpayers must file such a return if they estimate that (1) their taxable income for the year will be above a certain level, and (2) their withholding taxes for the year will not cover the total tax they will owe. For example, they may have to file an estimated tax return if they will receive considerable taxable income from which no withholding taxes will be collected. In an estimated tax return, taxpayers estimate their taxable income for the coming year and determine how much tax they will owe. They subtract the withholding taxes they will pay from the total tax they will owe. The difference is their estimated tax. They may pay this tax in one sum or in quarterly payments. Taxpayers who make late payments or underestimate their tax by an excessive amount must pay a penalty.

In March 2020, the IRS announced that the deadline for filing federal income tax forms, and for paying federal income tax, for the 2019 tax year had been extended from April 15, 2020, to July 15, 2020. The extension, which required no additional forms to be filled out, was provided as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the worldwide spread of a severe respiratory disease.

Processing income tax returns.

The IRS computer system consists of service centers linked electronically with the National Computer Center in Martinsburg, West Virginia. The IRS handles nearly 150 million individual tax returns each year.

Each individual tax return is checked for mistakes in arithmetic and for failure to report such income as dividends from stock or interest received from banks. The computers compare each taxpayer’s return with the IRS records on that person. Disagreements between taxpayers and the IRS are handled by the U.S. Tax Court. People who try to evade the tax by underreporting income or exaggerating deductions may receive stiff penalties, including prison terms. See Tax Court, United States .

State and local income taxes

Many state governments levy individual and corporate income taxes, and many local governments also collect an individual income tax. In some states, corporate and individual income taxes are the chief source of revenue for the state.

State and local income tax rates are lower than the federal rates, with tax rates that are either progressive or proportional. In most communities that have a local income tax, the tax rates are proportional. Some communities levy an income tax on all people who work in the community, including those who do not live there.

History of U.S. income taxes

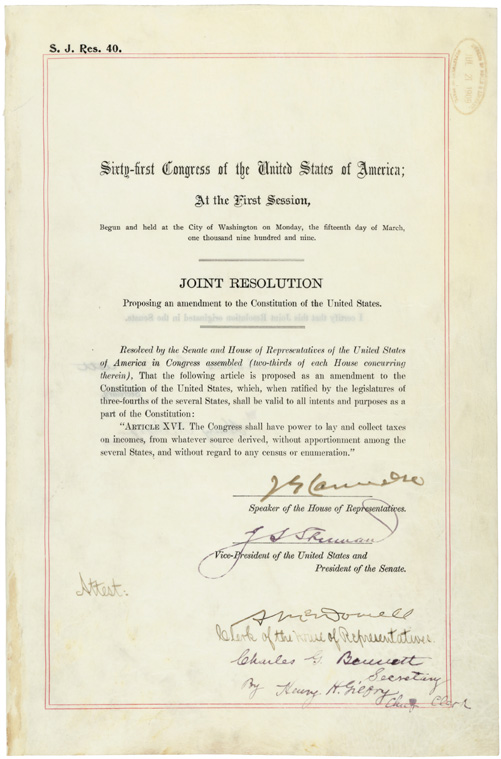

Some states levied an individual income tax before 1850. The federal government first collected an income tax in 1863. Congress had passed individual income tax laws in 1861 and 1862 because the Union government needed revenue to pay the cost of the American Civil War (1861-1865). The tax ended in 1872. Congress passed another income tax law, in 1894, but the Supreme Court of the United States declared it to be unconstitutional. The court based this decision on a statement in the Constitution that any tax levied directly on individuals must be levied in proportion to a state’s population. That is, a higher total tax had to be collected from a state with many people than from one with fewer people. An income tax was not found to meet this requirement.

In 1909, Congress passed a law providing for a kind of corporate income tax. The Supreme Court declared the law constitutional. To avoid future adverse court decisions, backers of an individual tax worked to amend the Constitution. In February 1913, the 16th Amendment removed the requirement that an income tax be levied in proportion to state population. The Underwood Tariff Act of 1913 included an income tax section.

Since 1913, the income tax laws have changed many times, and income tax rates have increased greatly. For example, withholding of employee income taxes began in 1943. Simplified returns and standard deductions came into use in 1944. In 1948, new provisions allowed exemptions for blindness and old age, and split-income joint returns for married couples. The Tax Reform Act of 1969 was a major revision of the income tax laws. It eliminated some situations in which corporations and individuals could legally avoid paying income taxes.

The Tax Reform Act of 1986 was probably the most important change in income tax legislation since the 1940’s. The act sharply reduced the level of tax rates and the number of tax brackets. It also greatly increased the tax base by restricting deductions, credits, and exclusions. The act established five rates ranging from 11 to 38.5 percent for the individual income tax. These rates replaced 14 brackets with rates ranging from 11 to 50 percent. The act also increased the size of personal exemptions for individuals, spouses, and dependents.

During the 1990’s, changes in tax laws introduced many new deductions, credits, and exclusions. The tax rates also increased. In 1990, Congress established a top individual income tax rate of 31 percent for people with the largest incomes. In 1993, Congress added individual income tax rates of 36 and 39.6 percent. It also raised the rate for some corporations. The Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 added new credits for dependent children and for college tuition.

In the early 2000’s, Congress significantly reduced individual income tax rates. It also added an individual rate of 10 percent for people with the smallest incomes and increased several deductions and credits. In 2018, Congress passed modest reductions to individual tax rates and reduced the corporate income tax to a proportional rate of 21 percent.