Indigenous peoples of the Americas are the first people who lived in North America or South America, and their descendants. Indigenous means original or native. Indigenous people had been living in the Americas for thousands of years before any Europeans arrived.

When Europeans first came to the Americas, almost every group of Indigenous Americans had its own name. Many of these names reflected each group’s pride in itself and its way of life. For example, the Delaware people of eastern North America called themselves Lenape, which means genuine people. Today, most Indigenous people refer to themselves primarily by the name of their own group, tribe, or nation. When referring to such groups together as a whole, many Indigenous people in the United States use the term Native Americans. Many descendants of the first peoples of Canada prefer the term First Nations. Other Indigenous peoples of Canada include the Inuit of the Arctic, and the Métis—people of mixed European and First Nations heritage.

The Vikings of northern Europe are believed to have explored the east coast of North America about A.D. 1000 and to have had some contact there with Indigenous people. But lasting contact between the first Americans and Europeans began with Christopher Columbus’s voyages to the Americas. In 1492, Columbus sailed across the Atlantic Ocean from Spain. He was seeking a short sea route to the Indies, which then included India, China, the East Indies, and Japan. Europeans did not then know that North and South America existed. When Columbus landed on an island in the Caribbean Sea, he did not realize he had come to a New World. He thought he had reached the Indies, and so he called the people he met Indians. For this reason, Indigenous Americans are sometimes called American Indians.

Most scientists think people first came to the Americas from Asia at least 15,000 years ago. Other scientists believe people may have arrived as early as 35,000 years ago. At the time these people came, huge ice sheets covered much of the northern half of Earth. As a result, much of Earth that is now underwater was dry land. One such area that was dry then but is submerged now is the Bering Strait, which today separates the region of Siberia in Russia and the state of Alaska in the United States. The migrants, following the animals that they hunted, wandered across this land, a distance of about 50 miles (80 kilometers). By 12,500 years ago, the first Americans and their descendants had spread throughout the New World and were living from the Arctic in the north to southern South America.

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas spoke hundreds of different languages and had many different ways of life. Some groups lived in great cities and others in small villages. Still others kept moving all year long, hunting animals and gathering wild plants.

The Aztec and the Maya of Central America built large cities. Some of the Aztec cities had as many as 100,000 people. The Maya built special buildings in which they studied the moon, the stars, and the sun. They also developed a calendar and a system of writing.

Many of the people of eastern North America lived in villages. They hunted and farmed, growing such crops as maize (corn), beans, and squash. At the southern tip of South America, people lived in small bands that moved from place to place in search of food. They ate mainly fish and berries. The peoples of this region spent so much time searching for food that they seldom built permanent shelters, made clothes, or developed tools.

The history of the New World includes the story of relations between Indigenous groups and European explorers, trappers, and settlers. Most of the encounters between Indigenous and European people were friendly at first. Indigenous people taught the newcomers many things. European explorers followed trails forged by Indigenous Americans to sources of water and deposits of copper, gold, silver, turquoise, and other minerals. Indigenous people taught Europeans to make snowshoes and toboggans and to travel by canoe. Food was another of the important gifts provided to the Europeans. Indigenous people grew many foods that the newcomers had never heard of, such as avocados, corn, peanuts, peppers, pineapples, potatoes, squash, and tomatoes. They also introduced the Europeans to tobacco.

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas, in turn, learned much from white people. The Europeans brought many goods that were new to the Americas. These goods included metal tools, guns, and liquor. The Europeans also brought cattle and horses, which were unknown to the Indigenous people of the Americas.

The Europeans and the Indigenous people had widely different ways of life. Some Europeans tried to understand the ways of Indigenous people and treated them fairly. But others cheated them and took their land. When Indigenous people fought back, thousands of them were killed in battle. At first, they had only bows and arrows and spears, while the Europeans had guns. Even more Indigenous people died from measles, smallpox, and other new diseases introduced by Europeans.

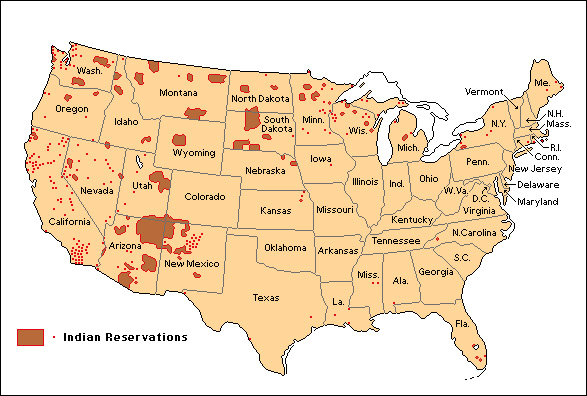

As the Europeans and their descendants moved westward across North America, they became a greater and greater threat to Indigenous ways of life. Centuries later, most of the remaining Indigenous people were moved onto lands known as reservations or reserves. Today, most of the descendants of the first peoples of North America still do not completely follow the ways of other North Americans. In some areas of Central and South America, several tribes have kept their language and way of life. But most of the tribes have become part of a new way of life that is both Indigenous and European.

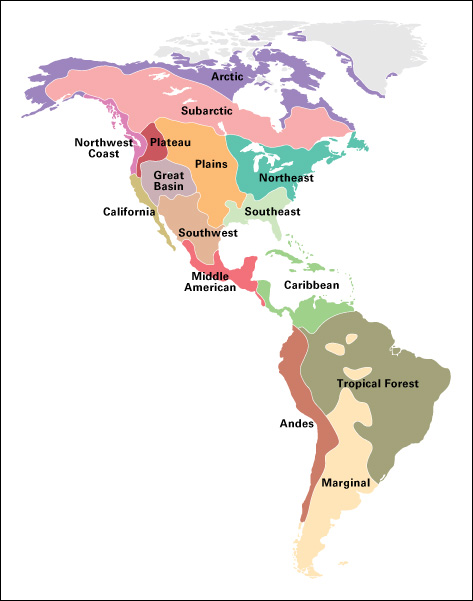

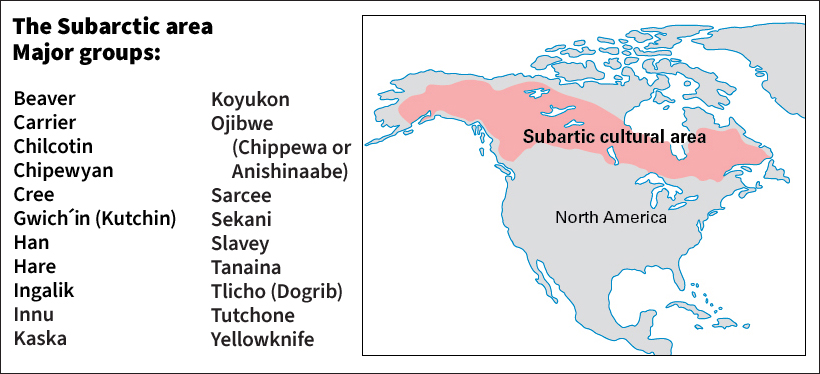

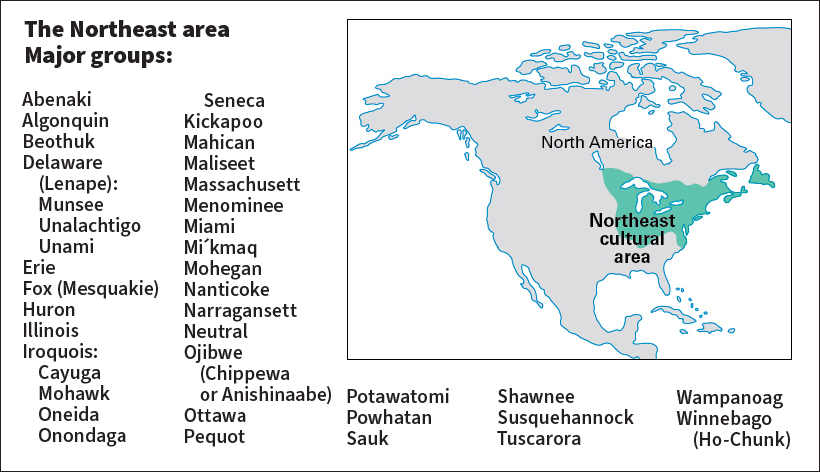

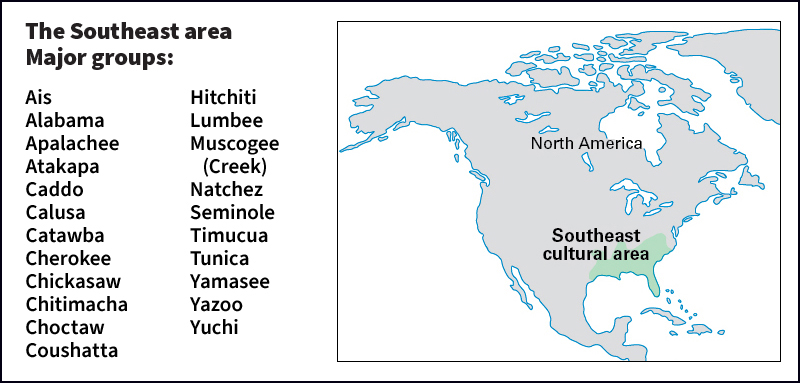

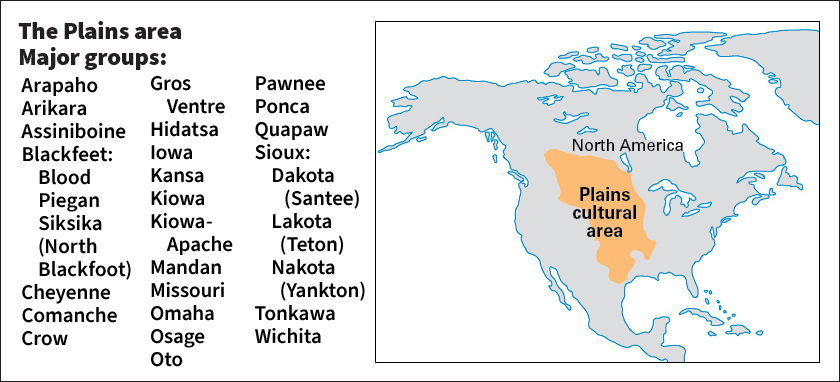

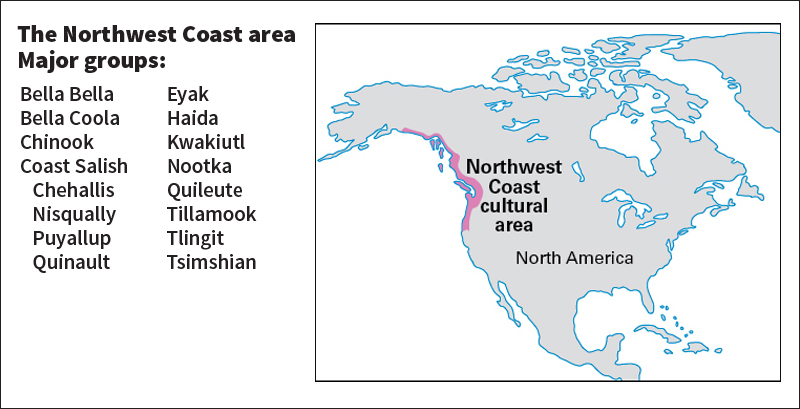

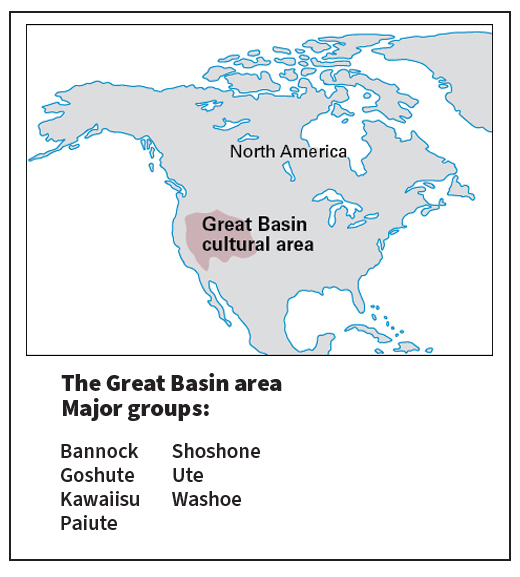

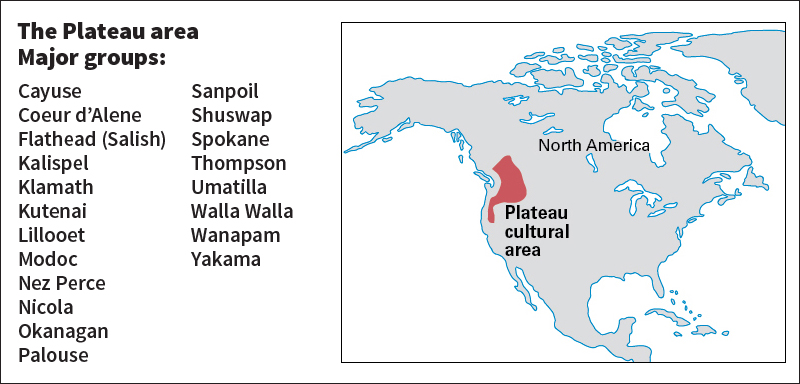

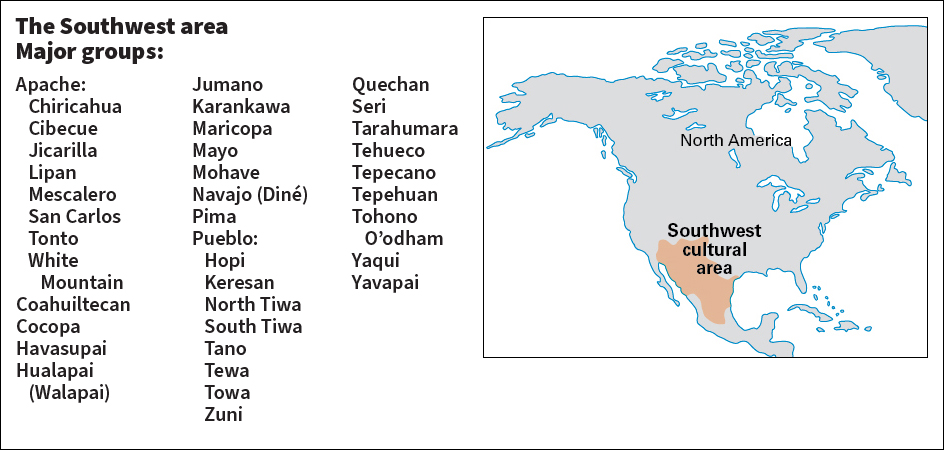

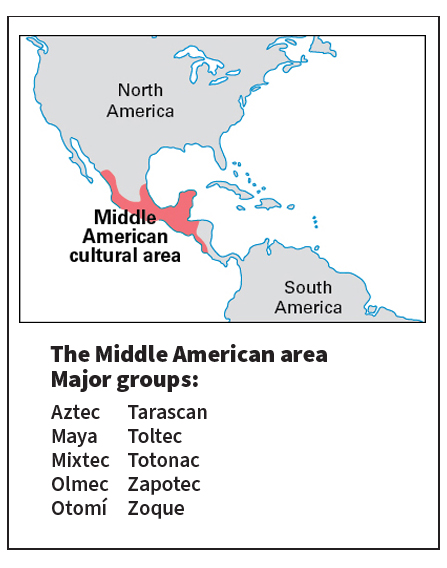

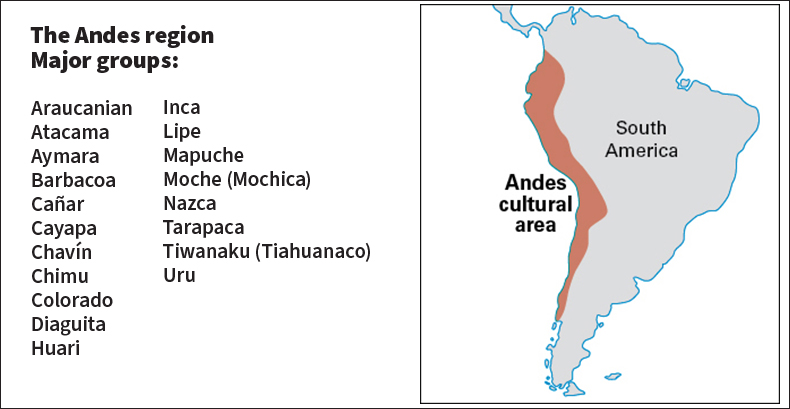

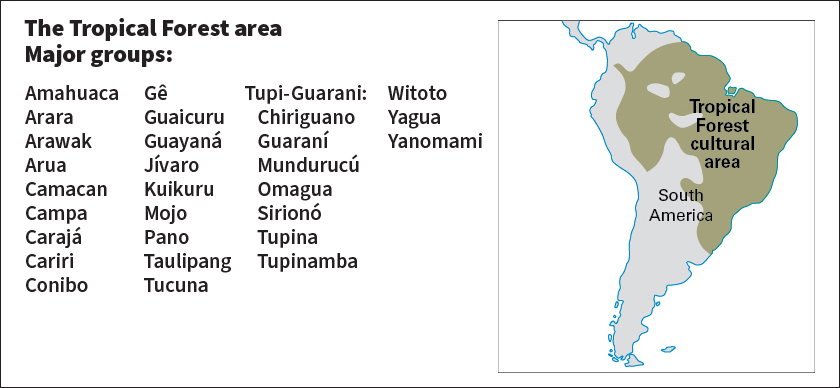

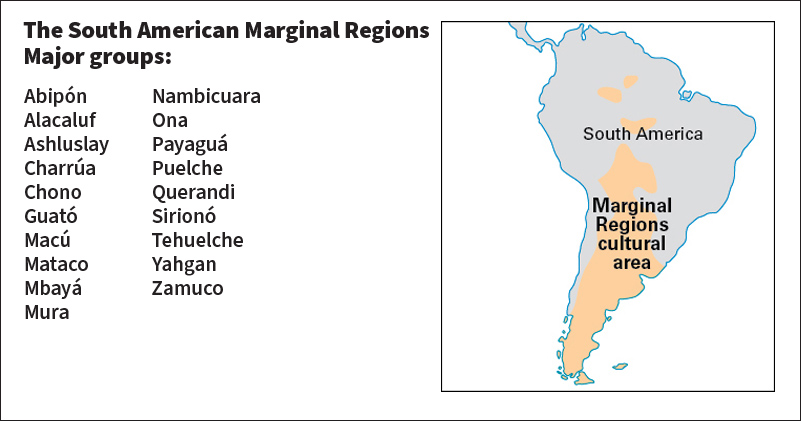

Scholars called anthropologists, who study human culture, classify the hundreds of North and South American Indigenous tribes into groups of tribes with strong similarities. These groups are called culture areas. This article discusses Indigenous groups in terms of 15 culture areas. The culture areas of Canada and the United States are (1) the Arctic; (2) the Subarctic; (3) the Northeast, often called the Eastern Woodlands; (4) the Southeast; (5) the Plains; (6) the Northwest Coast; (7) California; (8) the Great Basin; (9) the Plateau; and (10) the Southwest. Those of Latin America are (1) Middle America, (2) the Caribbean, (3) the Andes, (4) the Tropical Forest, and (5) the South American Marginal Regions.

The first part of this article describes the family life and other activities of the North and South American peoples before Europeans came. Then the article tells how the first Americans came to the New World and spread over the two continents. Next it describes the ways of life in the culture areas. The article then traces the destruction of Indigenous America and ends with a discussion of Indigenous people in the Americas today.

Family life

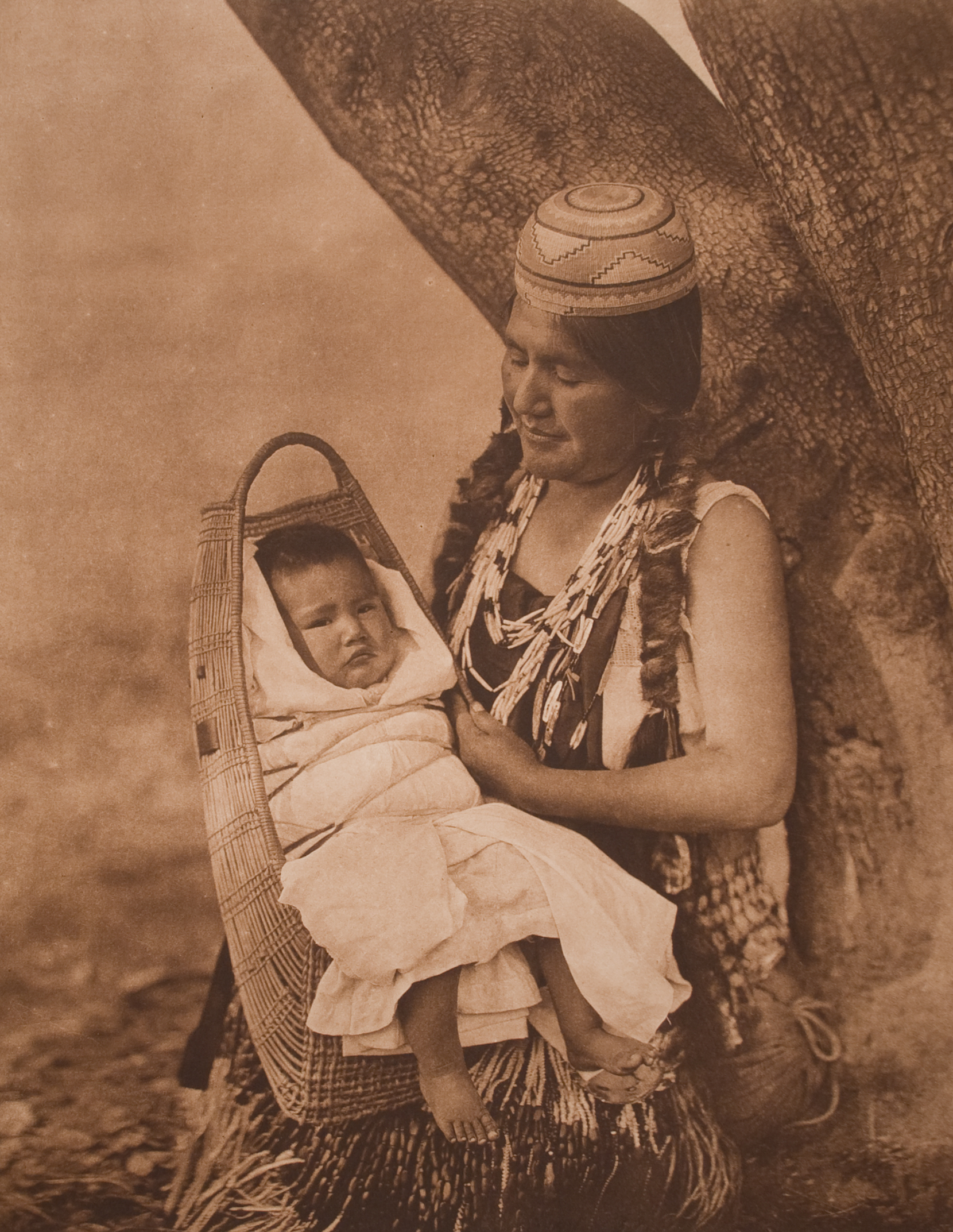

Most daily activities of an Indigenous American family centered on providing the main necessities of life—food, clothing, and shelter. Some times of the year were busier than others. Among the salmon-fishing tribes of North America, for example, the spring and summer were the seasons for catching and storing fish. The winter was a relaxed time of year when many ceremonies and social gatherings were held.

Men and women usually had separate tasks. For example, both men and women were often involved in providing food. But they did so in different ways. In some areas, the women gathered wild plants for food, and the men hunted. In the Northeast and Southeast culture areas, the men hunted, and the women farmed the land. In parts of what are now Arizona and New Mexico and in Middle and South America, the men did the farming. The women gathered plants. In all areas, women were generally responsible for preparing the food.

Marriage.

Many Indigenous people married at an early age—the girls between 13 and 15 and the boys between 15 and 20. In some tribes, the parents or other relatives chose the marriage partners for the young people. In other tribes, especially those of North America, a young man could select his own mate. He had to convince the girl and her parents that he would make a suitable husband. In many cases, he offered them valuable gifts to win their consent.

Throughout most of the New World, marriage was a family affair and not a religious ceremony. The boy’s family usually gave presents to the bride’s family. Many newly married couples lived with the girl’s family—and the husband worked for her family—until the birth of a child. Then the couple might establish their own home. But they generally did not move to a new home in a new area. Many other newly married couples joined an existing family group or lived close to one. Some of the couples moved in with other relatives of the woman or with the relatives of the man. This extended family shared the daily work of the household, including the raising of children.

Many Indigenous American societies allowed men to have more than one wife. But this practice was more common among rich or powerful men. Certain tribes strictly limited men to one mate, such as the Iroquois and the Pueblo of North America.

After a man died, his wife would often live with his brother as husband and wife—even if the brother was already married. Similarly, if a woman died, her family would probably be expected to give her husband another unmarried daughter to replace her.

Children.

Most Indigenous American families were small because many children died at birth or as babies. But the youngsters usually had plenty of playmates. Many extended families included cousins, in addition to a child’s own brothers and sisters.

Children were praised when they behaved well and shamed when they misbehaved. Before the arrival of Europeans, only the Aztec and Inca had regular schools. Boys and girls of other Indigenous groups learned to perform men’s and women’s jobs by helping their parents and older brothers and sisters. Games made Indigenous children skillful and strong.

After most boys reached their early teens, they went through a test of strength or bravery called an initiation ceremony. Many went without food for a long period or lived alone in the wilderness. In some tribes, a boy was expected to have a vision of the spirit that would become his lifelong guardian. Some groups also had initiation ceremonies for girls. A teenager who successfully completed an initiation ceremony was considered an adult and ready to be married.

Family groups.

In many areas, a family group was even larger than an extended family. A clan, for example, consisted of a group of relatives who had a common ancestor. The members of a clan typically were related through either the men of the family or through the women, but not through both. Clan members were usually ready to help one another.

Another type of group was the association. Associations resembled clans, but the members were not related. The tribes of the North American Plains had associations for men. Many of these groups were organized according to age classes. Youths joined a boys’ association and then moved on to other associations at various stages in their lives. As adults, they could join warrior societies and other associations.

Sometimes tribes were divided into halves called moieties (pronounced MOY uh teez). Moieties often played each other in games. They also divided various tasks and responsibilities. For example, members of one moiety might help with the burial of members of another group and comfort them in time of mourning.

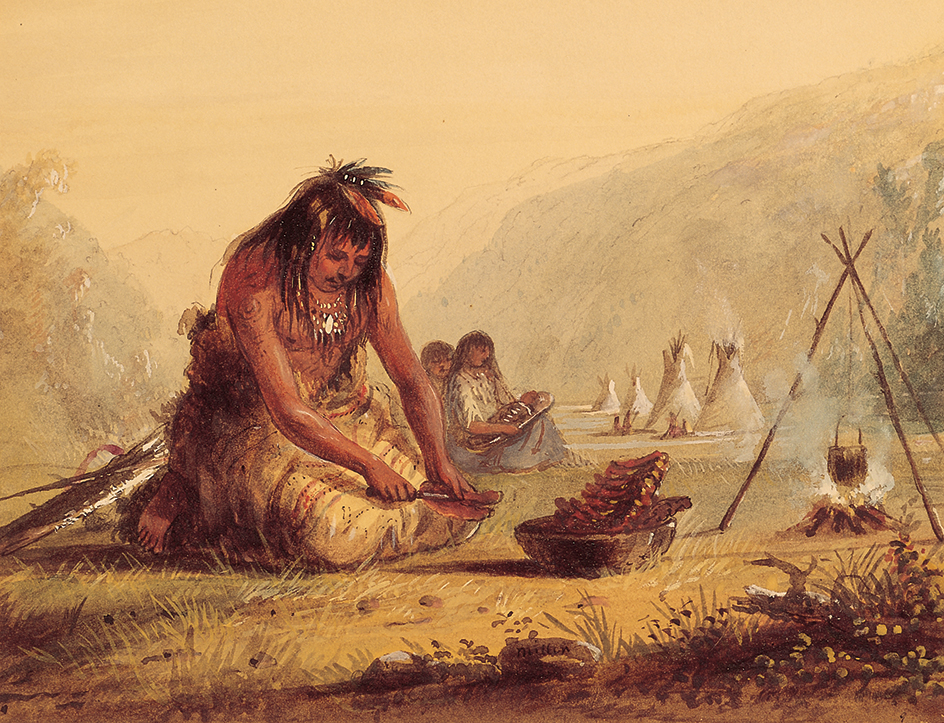

Food

that Indigenous people ate depended on where they lived. Tribes that lived on the plains of what is now the United States, where buffalo and other game were plentiful, ate mainly meat. Meat was also the principal food of the peoples who inhabited the woodlands and tundra (frigid treeless plain) of present-day Alaska and Canada. The Pueblo of the Southwest and other farming groups lived chiefly on beans, corn, and squash. Potatoes were an important crop among the Inca. Indigenous groups in the tropical areas of South America made bread from the roots of bitter cassava, a small shrub. Tribes that lived near water caught fish and gathered shellfish. Most Indigenous groups ate berries, nuts, roots, seeds, and wild plants. They also gathered salt and collected maple sap wherever they could.

Indigenous people made a kind of tea from such plants as sassafras and wintergreen. Many Middle and South American people drank a mild beer that was known as chicha. They made it from corn, cassava, peanuts, or potatoes.

Indigenous people who ate mostly meat cooked it by roasting, broiling, or boiling. Farming peoples and others who ate chiefly vegetables developed various methods of boiling or baking. They often made pit ovens by lining holes in the ground with hot stones. Meat was preserved by smoking it or by drying it in the sun. Indigenous people in North America mixed dried meat with grease and berries to make a food called pemmican. Most people ate with their fingers, but some used spoons made from animal bones, shells, or wood.

Clothing.

Many Indigenous people made their clothes from animal skins and fur. Tanned deer hide, called buckskin, was one of the most common clothing materials throughout North America. Other materials included buffalo hides, rabbit fur, and bird feathers. Some tribes of the Northwest Coast of North America made cloth of bark and reeds, and the Pueblo wove cotton cloth. The Aztec, Inca, Maya, and some Caribbean peoples wove beautiful cloth made of cotton and wool.

People of the South American tropics often wore little or no clothing at all. In many tribes, a man wore only a breechcloth, a narrow band of cloth that passed between the legs and looped over the front and rear of a belt. Women wore simple aprons or skirts. Inhabitants of colder climates wore leggings, shirts, and robes. Some wore sandals or moccasins to protect their feet.

Shelter.

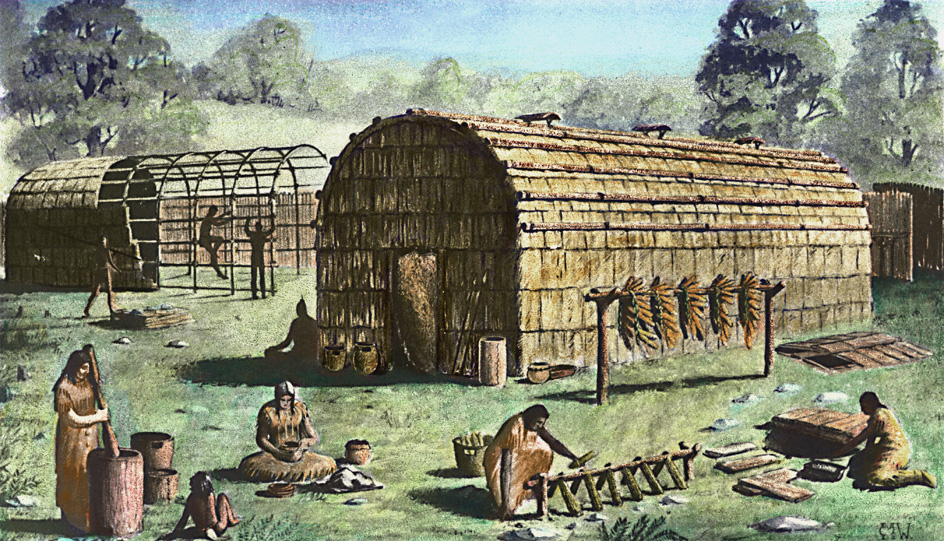

Many Indigenous people built a pole framework and covered it with leaves or bark, like the dome-shaped wigwam of the Northeast. The Iroquois followed a similar method in building their long, rectangular longhouses. The Iroquois called themselves the Haudenosaunee. This name refers to their dwellings and means we longhouse builders. Some longhouses were more than 100 feet (30 meters) long. The Apache and Paiute used brush and matting to make simple wickiups. The Pawnee and some other North American tribes made earth lodges. These had a log framework covered by brush, grass, and earth. In some cases, the framework was placed over a shallow pit. Poles or logs covered with earth formed the Navajo hogan. The Plains peoples built cone-shaped tipis (also spelled tepees) of buffalo skins. In other areas, people covered their tipis with animal skins or with tree bark. Groups living at the southern tip of South America also used skins to cover shelters called windbreaks, which were open on one side. The cliff dwellers and other Pueblo peoples used adobe (sun-dried bricks) to make many-storied “apartment houses.” Indigenous groups in Mexico and in the Andes Mountains of South America also used adobe.

Hunting, gathering, and fishing.

The Indigenous peoples of the Arctic, Subarctic, Northwest Coast, and some other areas hunted or fished for most of their food. They also hunted some birds only for the feathers, and they prized the fur of beavers and certain other animals. The people of California, the Great Basin, and the Plateau got most of their food by gathering wild seeds, nuts, and roots. Even in the Southwest and other farming areas, hunting, gathering, and fishing were important.

The most important game animals of North and South America included deer; rabbits and other small game; such birds as ducks, geese, and herons; such sea mammals as seals, sea lions, and whales; turtles; and snakes. Bear, buffalo, caribou, elk, and moose lived only in North America. Animals that were hunted mainly in South America included the guanaco, jaguar, peccary, rhea, and tapir.

Indigenous people hunted with the same kinds of weapons they used in war. Many bows and arrows, spears, and clubs had special features for hunting. For example, some hunters used unsharpened arrows to shoot birds in trees. These arrows stunned the birds so that they fell to the ground. The Hopi stunned small game with a kind of boomerang.

Indigenous people caught fish with harpoons, hooks and lines, spears, and traps and nets. Tribes of the Northwest Coast also used long poles called herring rakes. These poles had jagged points and could catch a number of herring at one time. In tropical South America, people stood on river sand bars and shot fish with bows and arrows. Both North and South American peoples used drugs to catch fish. In one method, Indigenous people chopped up certain plants and threw them in the water. These plants stunned the fish. Then the fish could be easily scooped out of the water.

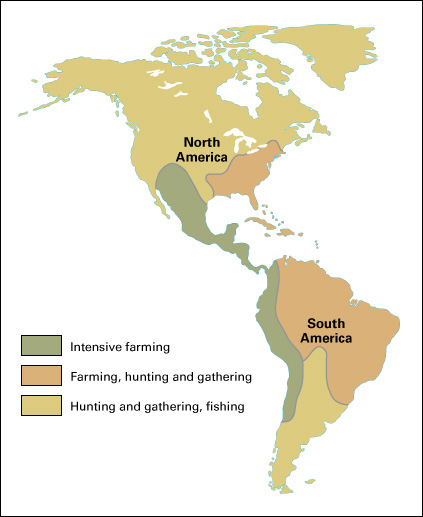

Farming

by the Indigenous peoples of the Americas consisted mainly of growing corn, squash, and beans. Other crops included avocados, cacao, cassava, coca, cotton, guavas, peanuts, peppers, potatoes, tobacco, and tomatoes.

Farming tools included pointed sticks for digging and hoes made of wood, stone, bone, or shell. Farmers planted corn in small hills arranged in rows. Some tribes of eastern North America used dead fish to fertilize the soil. In the desert areas of the Southwest, the early Hohokam people dug long irrigation ditches to bring water to their crops. Irrigation was even more highly developed among the groups that lived in what is now Mexico and among the peoples of the Andes Mountains. These people also cut hillside terraces to increase the amount of farmland by using mountain slopes.

Indigenous people of the Northeast and the Tropical Forest used slash-and-burn farming methods. They cut down a number of trees and burned them. Then they planted their crops among the trunks. The ashes from the burned trees served as fertilizer.

Indigenous people in the Caribbean area and in what are now Mexico and the Southern United States raised turkeys. Andean people kept llamas and alpacas for food and wool and also used them as beasts of burden. Dogs were the only other tame animals in North and South America.

Transportation.

Before the arrival of the Europeans, Indigenous people lacked horses, oxen, and most other beasts of burden used in other parts of the world. As a result, the first Americans never developed the wagon wheel, though they had discovered its principle. The Inca and Maya built excellent roads, but most other Indigenous groups used narrow trails.

Travel by water was the most common means of transportation. Many travelers used bark canoes, which were light and easy to carry. Some large dugout canoes carried as many as 60 people. People also made light boats of reeds. The Plains people stretched buffalo skins over a round frame to make a bullboat. Inhabitants of the snowy north developed snowshoes and toboggans. Some favored groups, such as Inca nobles, traveled on wooden frames carried by servants.

The first Americans had few ways of carrying loads. The Plains tribes used dogs and, later, horses to pull a load-carrying frame called a travois << truh VOY >>. Andean peoples used alpacas and llamas as beasts of burden. But these animals could not carry heavy loads, so the people themselves carried most of their goods. People often supported a heavy load on their back with a pack strap called a tumpline. The strap was attached to both ends of the pack and stretched across the forehead.

Recreation.

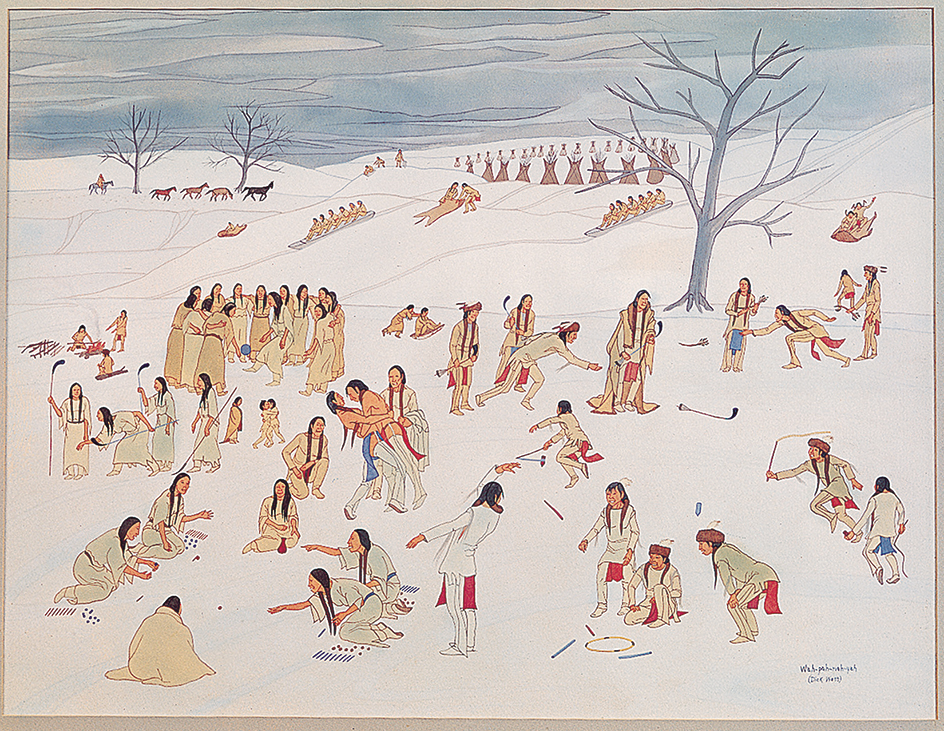

Almost all Indigenous people played games. Men and women usually played separately and had different games. Children played almost all the games that their parents enjoyed.

Footracing was popular in many areas. The Indigenous people of what are now northern Mexico and the southwestern United States particularly enjoyed this sport and sometimes ran over a 30-mile (48-kilometer) course. Indigenous Americans played many different kinds of ball games. In almost all these games, the players were not allowed to touch the ball with their hands. Stickball developed into the game of lacrosse. Usually, only women played shinny, or shinty, a kind of field hockey that was common in North America. The Aztec and Maya played a ceremonial game in which the players tried to bounce a large, hard rubber ball through a high vertical ring with their hips. Scoring was so difficult that the game ended when either team scored. In some cases, the captain of the losing team was sacrificed to the gods.

In the hoop-and-pole game, the players rolled a hoop along the ground and threw spears or sticks at it. They scored according to where the spears hit. The Arapaho, for instance, cut four marks around the edge of the hoop. They tried to strike the rolling hoop so that the stick fell directly on or below a certain mark. The peoples of the Southeast called this game chunkey and used a small stone ring as a target.

Many Indigenous Americans enjoyed shooting arrows as a sport. They used several kinds of targets, including pieces of bark, woven grass, or an arrow stuck in a tree. Northern groups enjoyed a game called snow snake, in which each player tried to slide a dart or spear farthest on snow or ice.

Quieter amusements included several games of chance. Guessing games were popular in North America. In the hand game, one or more players on a team held marked sticks in their closed fists. The players on the other side tried to guess where a certain stick was. The hiding side sang loudly to confuse the guessers, and both sides bet on the results.

Government

For the most part, the Indigenous peoples of the Americas lived in small groups and shared in making important decisions. Some groups, including the Aztec in Mexico and the Inca in Peru, developed complicated systems of government. But most tribes did not, because they had no need for such systems.

Bands.

Families of Indigenous people joined together to form local groups called bands. These groups ranged in size from about 20 people to as many as 500. The size of a band resulted mainly from the number of people that the nearby area could support. If there was plenty of game or the land was rich, the band would probably be large. If food was scarce, the band would be small.

When faced with a problem, such as a shortage of food, the members of a band would gather around a fire to discuss it. They might offer prayers to their gods. In some areas, such a meeting was called a powwow. Some bands had permanent leaders, but others chose different leaders for different problems.

Tribes

were larger than bands. Hundreds of tribes lived in the Americas when Columbus arrived. All the members of a tribe lived in the same general area. They spoke the same language and had the same religious beliefs.

Forms of tribal leadership varied. Tribes might have one or more leaders, often referred to as chiefs. In some tribes, one chief might be in charge of the tribe during peacetime. Another would lead the tribe in war. In some tribes, a person had to belong to a certain family, band, or clan to become a chief.

Although many tribes did not have a single permanent leader, certain groups called chiefdoms did. In both types of tribes, decisions were typically made by general agreement after a meeting of the tribal council. This council consisted of members of the tribe who were respected for their wisdom or abilities.

Federations.

Some tribes in North America joined together to form groups called federations. The most famous federation was the Iroquois League, originally made up of the five Iroquois tribes—the Mohawk, Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca, and Cayuga. Historians believe that the Iroquois leader Hiawatha helped found the federation to stop the fighting among these neighboring tribes. Other federations, such as the Cherokee and Muscogee (Creek), were formed to fight common enemies or to solve various problems.

Empires and states

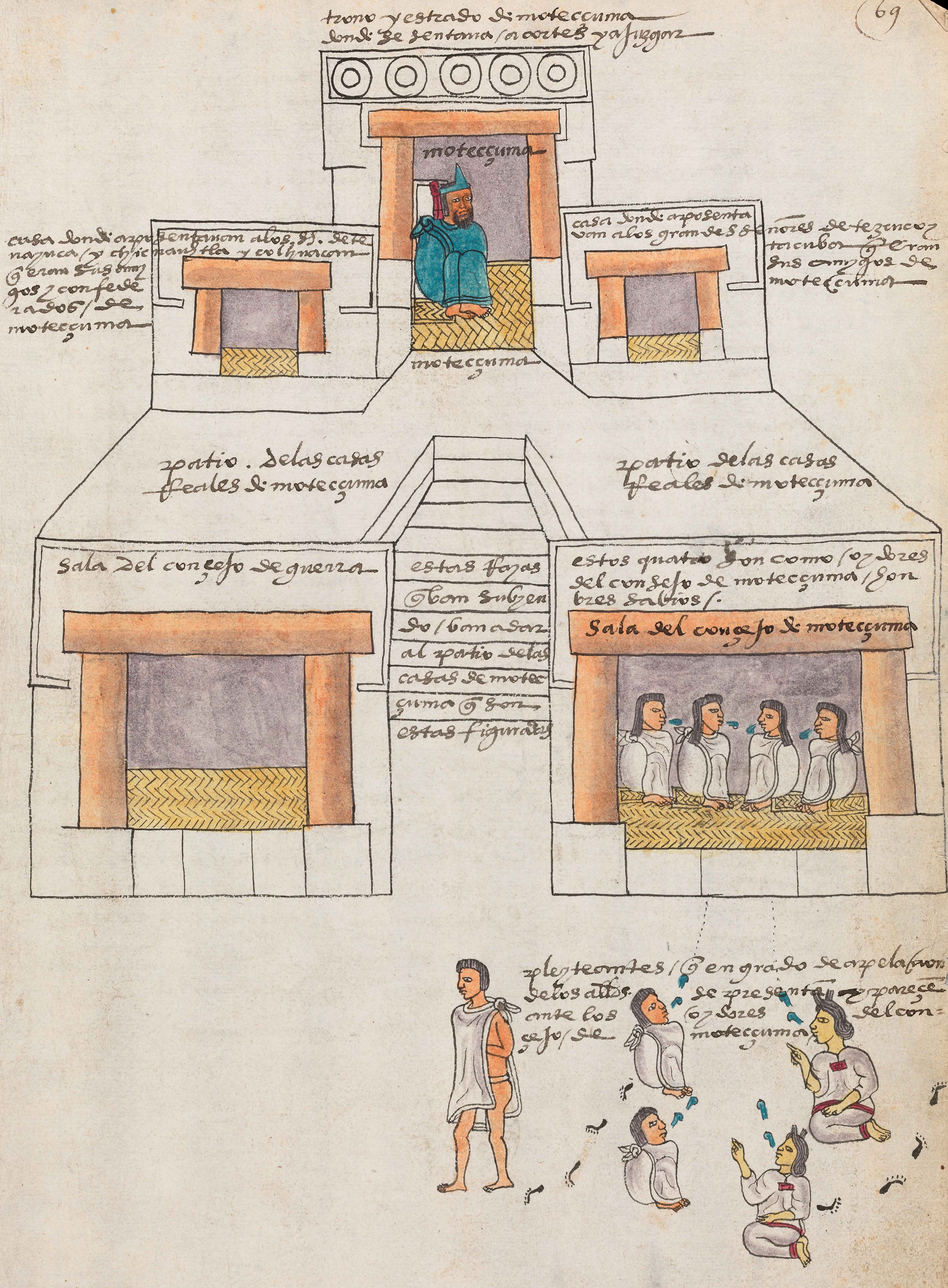

existed only in Middle and South America. An emperor ruled the huge Aztec state in Mexico, and the people were divided into social classes. In the Inca empire, which stretched along the Andes Mountains in South America, a god-king ruled from 3 1/2 million to 7 million people. Among the Maya of Middle America, large cities ruled over the surrounding areas. Many of these cities were home to tens of thousands of people.

A formal state may have started to develop among the Natchez people and their neighbors in the Southeastern United States. The arrival of the Europeans halted its development. The Natchez had a powerful king.

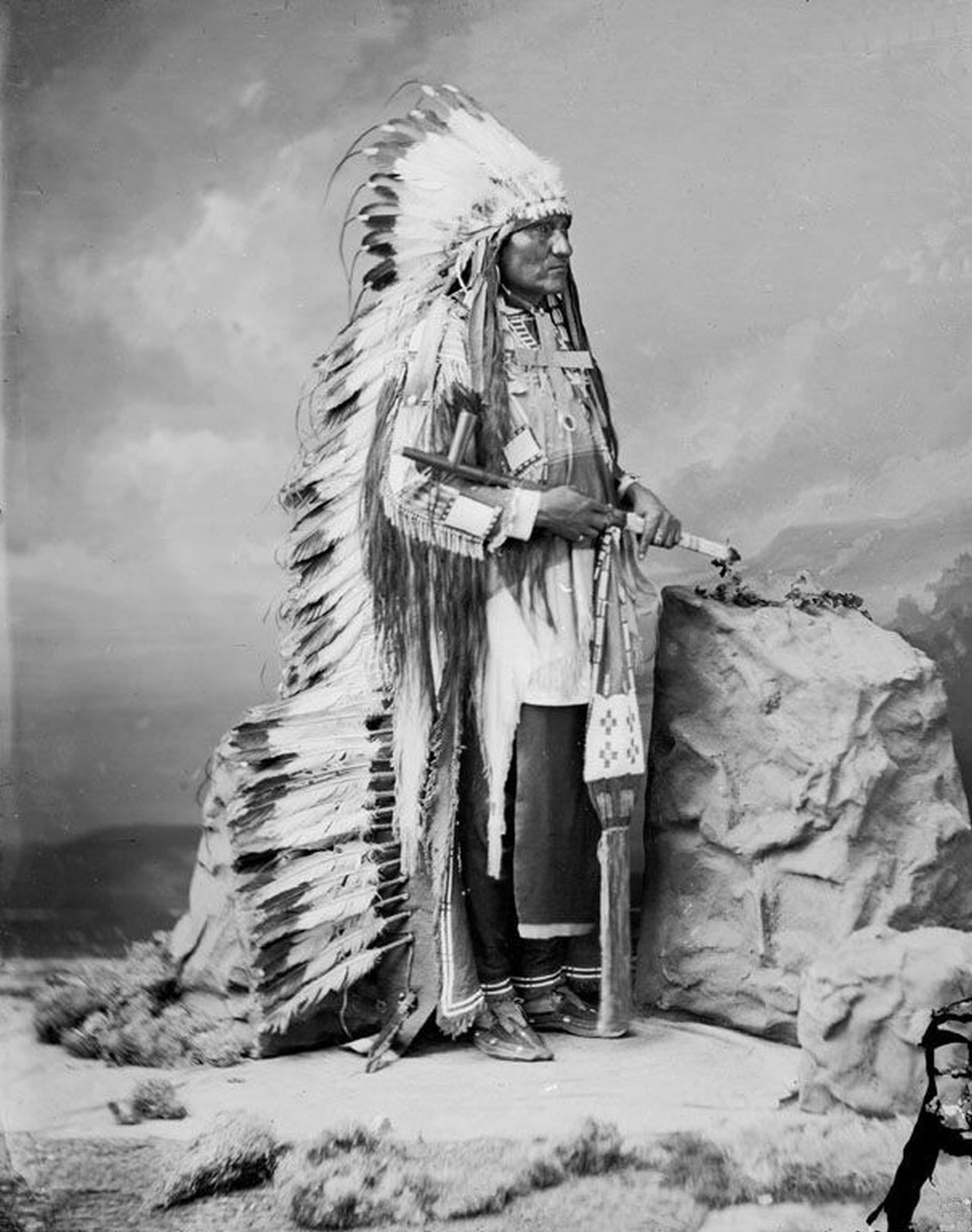

Warfare

Wars occurred from time to time among the tribes of the Americas. But not all tribes took part in warfare. Many tribes opposed fighting, and others were so small that they did not have enough warriors to fight a war. Many of the leaders who tried to defend their tribes and land against the advance of white people became famous warriors. They included King Philip, a Wampanoag; Pontiac, an Ottawa; Tecumseh, a Shawnee; Osceola, a Seminole; Crazy Horse, of the Oglala band of the Lakota, or Teton Sioux; and Geronimo, an Apache.

Weapons.

The bow and arrow was probably the most common weapon throughout North and South America. Some South American tribes put poison on their arrowheads. Many Indigenous warriors fought with spears and war clubs. The peoples of eastern North America developed a special type of club known as the tomahawk. A weapon of the Aztec consisted of pieces of obsidian (volcanic glass) stuck into a wooden club. South American fighters used blowguns and slings.

Why conflicts occurred.

Warfare was sometimes the only way of settling disputes between tribes. A council, made up of the chiefs of tribes that had joined together, settled many arguments between tribes. But warfare might result if the council could not settle a dispute.

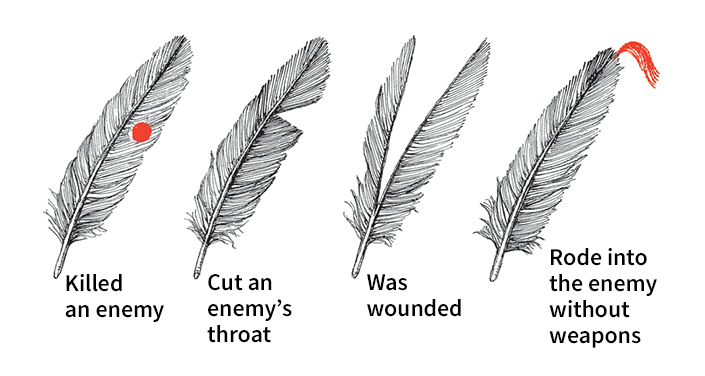

Warfare gave warriors a chance to achieve high rank in their tribes. On the Plains, it was considered braver to touch a live enemy and get away than to kill the enemy. This act was known as counting coup << koo >>. Warriors on the Plains carried a coup stick into battle and attempted to touch an enemy with it. Those warriors who counted coup wore eagle feathers as signs of their courage.

The scalp of an enemy was a war trophy in parts of North America. Some Europeans encouraged scalp hunting in North America by paying Indigenous people who were friendly to the newcomers for the scalps of enemies. The Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean and Tropical Forest regions fought for war honors and trophies that included skulls and shrunken heads as well as scalps.

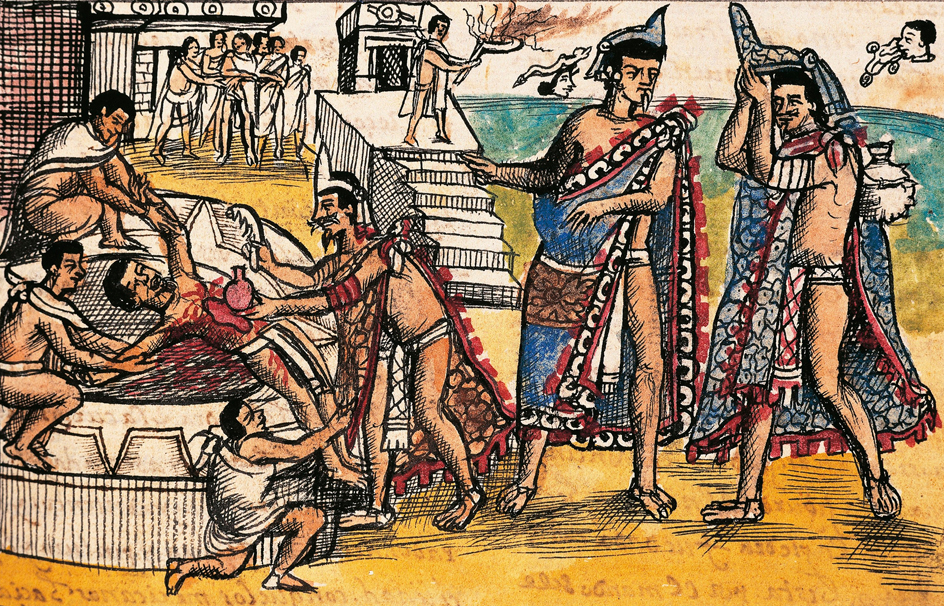

The Aztec fought not only to enlarge their territory but also to take captives for sacrifice to the gods. Human sacrifice was a major part of the Aztec religion. Only the Aztec and the Inca had full-time armies. In other tribes, warriors went back to hunting or farming after their battles. Some tribes, particularly the Northwest tribes and the Iroquois, enslaved their captives. The Witoto and Tupinamba tribes of the Tropical Forest sometimes killed war captives and then ate them. But the victims were not eaten as a source of food. The tribes believed the dead person’s strength and bravery would be passed on to the person who ate the flesh.

Warfare increased greatly in all areas after the Europeans came. It became the main way of settling disputes between Indigenous groups and white newcomers. The Europeans adopted Indigenous styles of warfare—ambush, surprise attack, and quick withdrawal. Indigenous groups began to use the Europeans’ guns and other weapons.

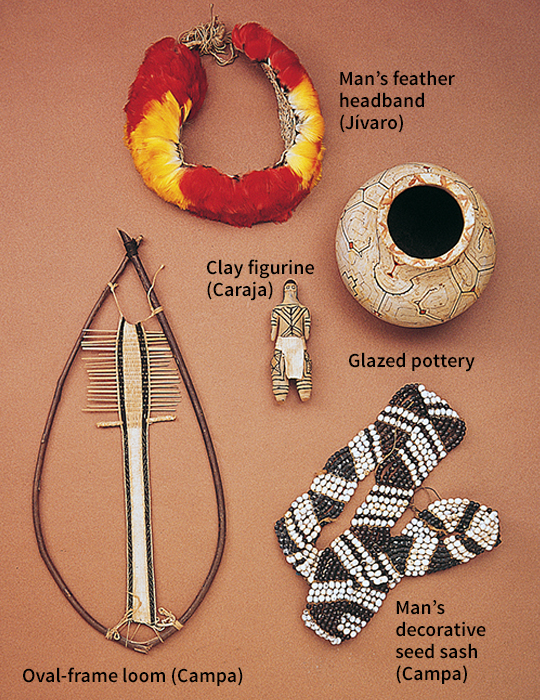

Arts and crafts

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas worked in many arts and crafts. For the most part, people tried to make everyday objects attractive as well as useful. Indigenous people also produced various forms of oral and written literature.

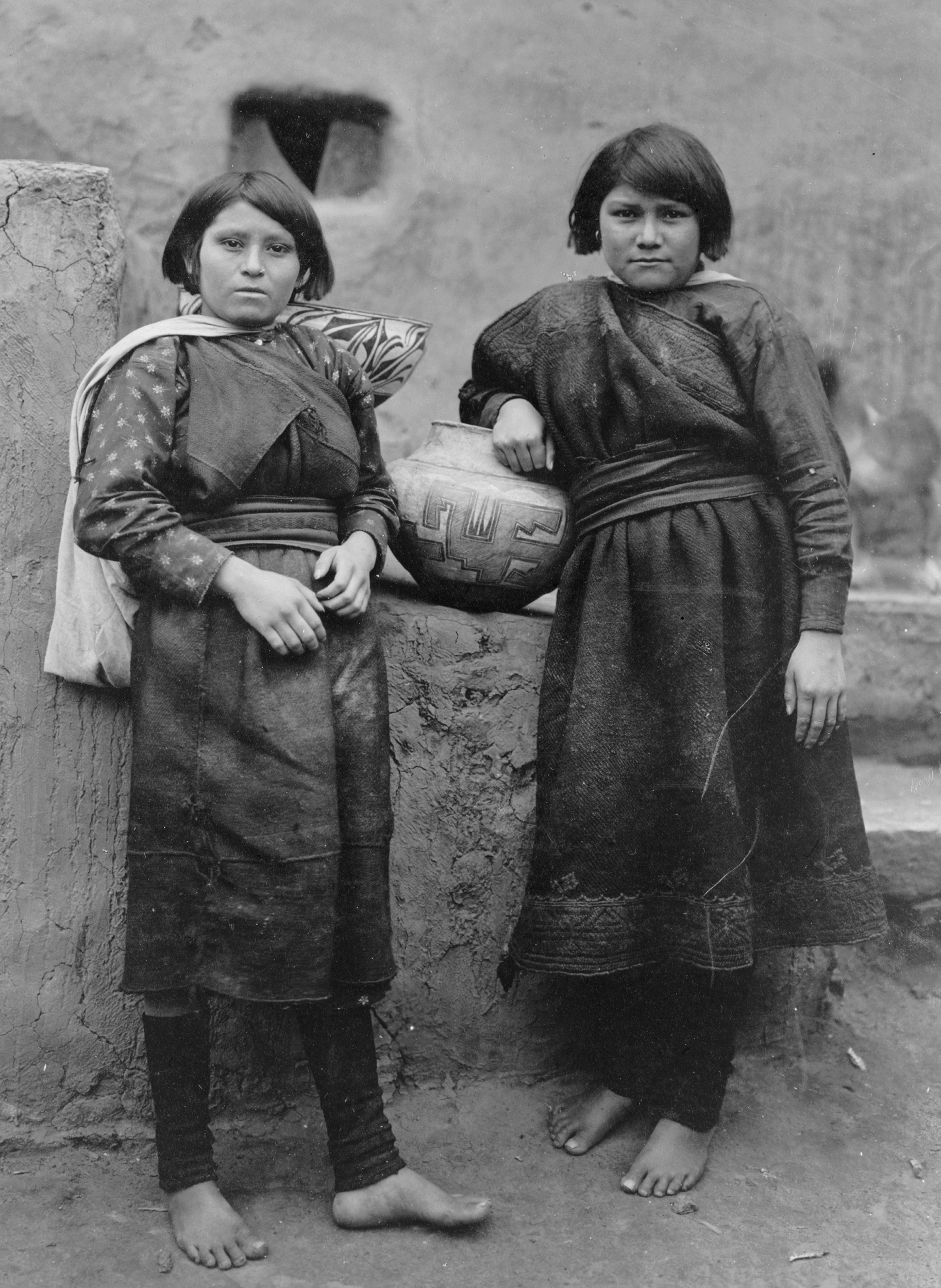

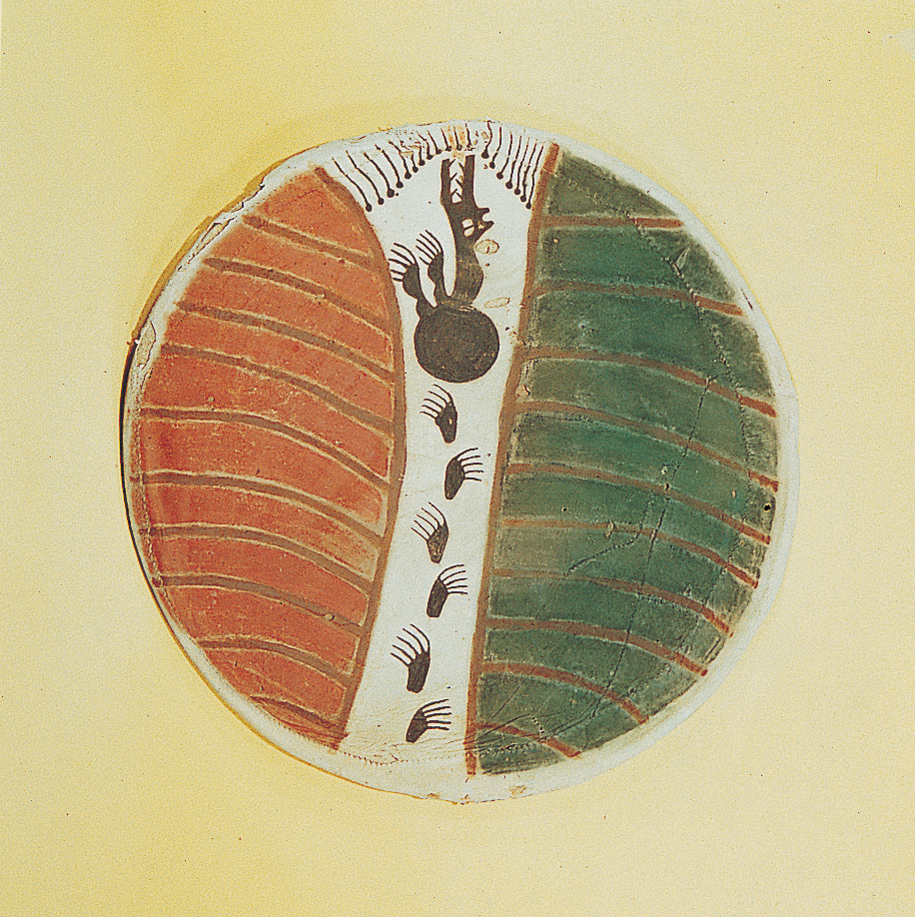

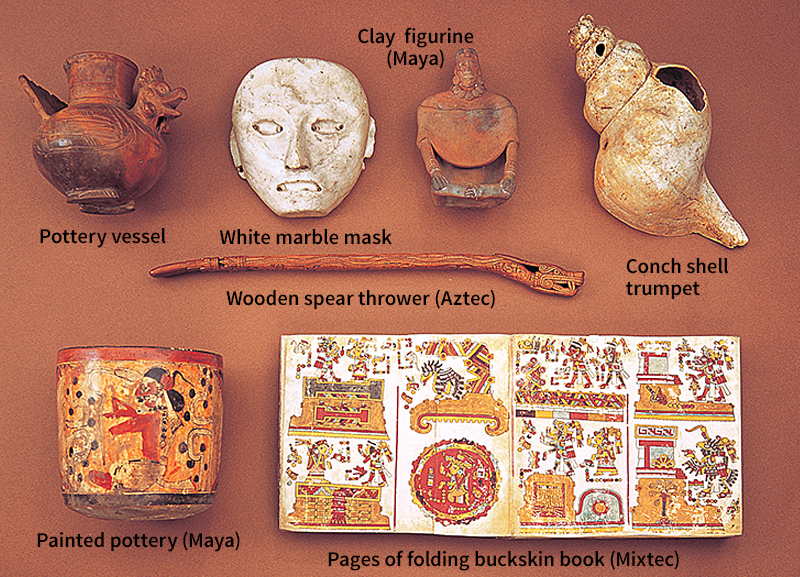

Pottery.

Indigenous people created a great variety of beautiful pottery. They made most of their pottery by the coil method, in which pieces of clay are rolled into slender strips and laid on top of one another in spiral fashion. Potters sometimes kept the coils on the pottery as decoration but often scraped the surface smooth.

Inca potters made some of the finest pottery in the New World. The Aztec and Maya painted some of their pottery with scenes of religious ceremonies. In North America, the early peoples of the Mississippi Valley made fine bowls and jars, many in the shape of animals.

Basketry.

Almost all Indigenous groups made baskets that they used to store and carry food. Indigenous people also wove fibers into mats and wall coverings, articles of clothing such as hats and sandals, and fish traps. The Pomo people, who lived in California, were probably the finest basket makers in the New World. The Pomo sometimes decorated their baskets with shells, feathers, and beadwork. Pomo baskets were woven so tightly that they could hold water.

Carving.

The Indigenous peoples of Middle America created elaborate carvings. Large sculptures were used to decorate ancient Aztec and Maya structures or were placed alongside the structures as monuments. The peoples of Middle America also carved jade, onyx, quartz, and other materials. Peoples of the Northwest Coast made fine woodcarvings. Their ceremonial wooden masks had movable parts. They also carved house posts, grave markers, and totem poles.

Metalwork.

The Andean people knew how to make bronze and how to cast, solder, and gild metals. The Caribbean peoples produced fine pieces of gold work. No such elaborate metalworking took place north of what is now Mexico. But Indigenous people in the Lake Superior region and the Northwest Coast hammered copper to form tools and weapons. They also cut hammered copper into decorative or ritual objects.

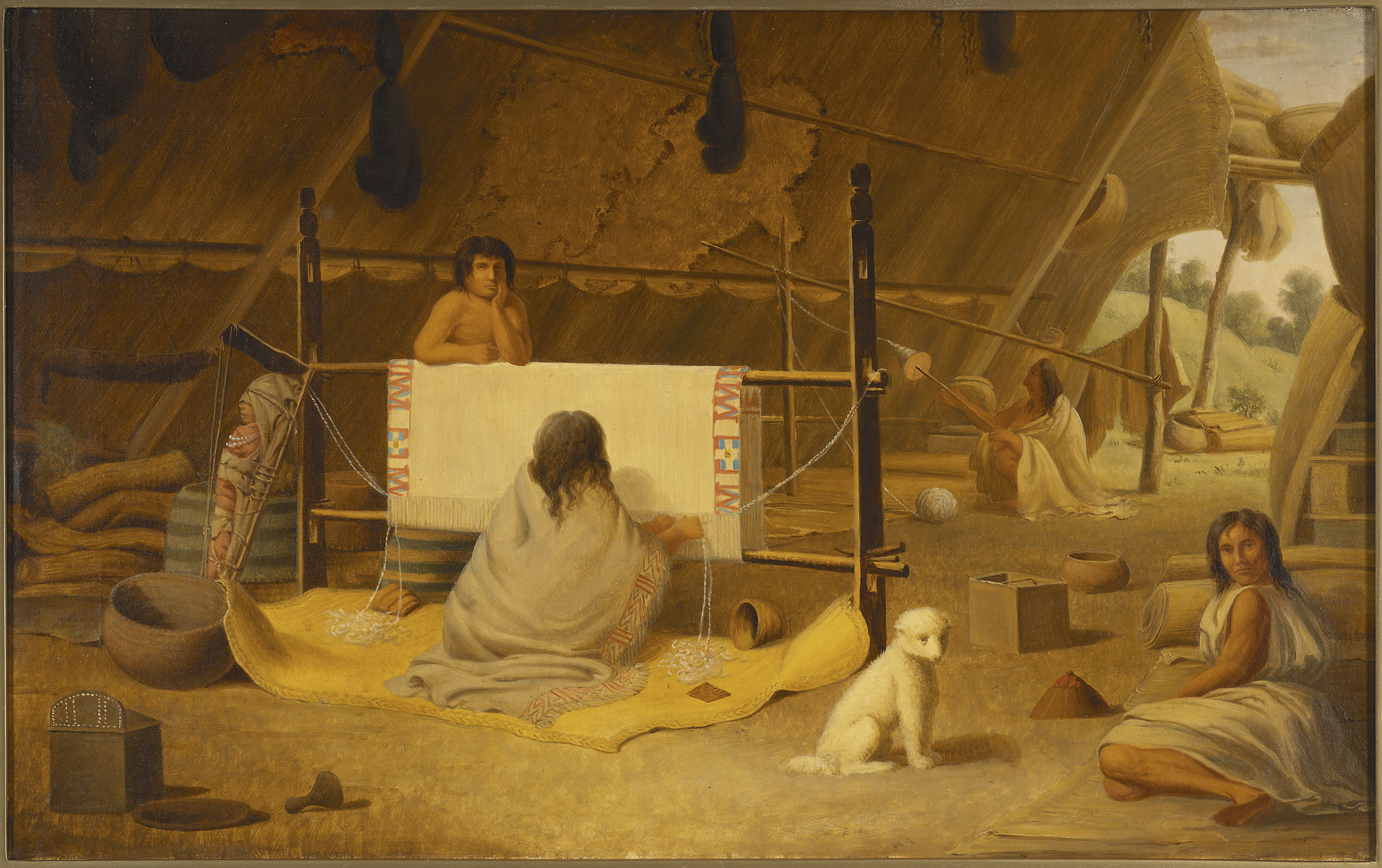

Weaving

was most common south of the Rio Grande. But the Pueblo of the Southwest wove cotton cloth before the arrival of the Europeans. The Navajo, or Diné, people took up wool weaving later and became famous for their blankets and rugs. Peoples of the Northwest Coast made beautiful blankets of cedar fibers and mountain-goat hair. Inhabitants of the Southeast wove plant fibers so well that the early European settlers thought the material was actually cotton cloth.

Weaving was also an important art among the Inca. Their weaving of cotton and of alpaca, llama, and vicuna wool was so fine that it has not been improved upon—even with power looms.

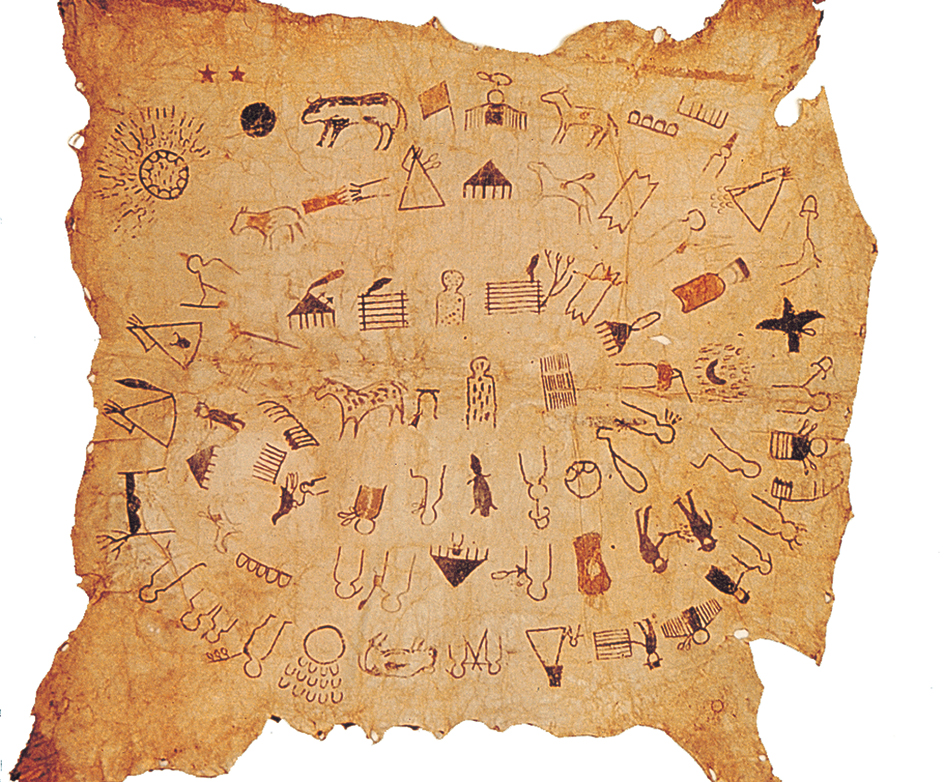

Painting.

Indigenous craftworkers usually combined painting with other arts. For example, much pottery of the Indigenous peoples of the Southwest and of the Aztec, Maya, and Inca had painted designs. The Aztec and Maya also made large wallpaintings of important ceremonies and historic events. Painted designs also decorated some woodcarvings of the Northwest Coast tribes. The Pueblo were the first to make sand paintings, and the Navajo improved on this ceremonial art.

Literature.

Most Indigenous groups handed down their folk tales and poetry by word of mouth for centuries. Some North American groups, such as the Ojibwe, recorded some of their tribal songs on bark. The Maya left behind manuscripts that tell of their ancient history. The Inca wrote dramas dealing with great military victories as well as with everyday life.

Religion

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas had no one religion any more than they had one way of life or one language. But certain religious beliefs were widespread. Most important was the belief in a mysterious force in nature. Indigenous people considered this unseen spirit power superior to human beings and capable of influencing their lives. People depended on it for success in the search for food and in healing the sick, as well as for victory in war.

Beliefs.

Most Indigenous people believed that the spirit power could be gained by certain people or through certain ceremonies. The power might be centered in some animals, areas, or things, making them powerful or dangerous. Some tribes had a name for the spirit power. The Iroquois called it orenda, and the Lakota referred to it as wakan tanka.

Some tribes believed in a Creator Spirit—an especially powerful god. But the great god belief was always accompanied by a belief in many other spirits or in the general spirit power.

The peoples of Middle America and the Andes had whole families of gods. The Aztec, for example, worshiped hundreds of gods. The Inca believed that their ruler was also a god—a god-king—and they worshiped him along with their other gods.

Indigenous people in some areas greatly feared the ghosts of the dead. But few people gave much thought to life after death or the idea of a heaven.

The guardian spirit.

One way of reaching the powerful spirit world was through a personal spiritual helper called a guardian spirit. Most Indigenous people believed that the spirit helped guide a person through the hardships of life. An individual might have one special guardian spirit, or different ones for different needs. Belief in a guardian spirit was common throughout most of the New World.

When boys—and, in some tribes, girls—reached their early teens, they went through an initiation ceremony to help them find a guardian spirit. Many went without food, sleep, or companionship until they saw a vision of their guardian spirit. Some wounded themselves to help bring a vision. This search for a vision of a guardian spirit is known as a vision quest.

Medicine people.

The spirit world could also be reached with the aid of a religious helper called a medicine maker or shaman. These helpers were believed to have close contact with the spirit world. They were sometimes called medicine men or medicine women because their tasks included treating the sick.

Some people believed that certain diseases were caused by an object in the body. Medicine people began their cure for such conditions with special songs and movements. They usually blew tobacco smoke over the sick person because tobacco was believed to have magical powers. Medicine people sucked on the body of the sick person until they “found” the object causing the illness. Then they spit out the object—usually a small stick or a stone that they had hidden in the mouth.

Medicine people had some knowledge of medicine. They set broken bones and used various herb remedies. Many plants they used are still given by doctors today. Curare arrow poison is used in treating hydrophobia and tetanus. Indigenous people also used quinine, which physicians prescribe to treat malaria. The Inca developed trephining, the removal of part of the skull. This surgery was often used to relieve pressure on the brain.

Occasionally, medicine people joined together to form a religious organization called a curing society. Such organizations included the Midewiwin Society of the Ojibwe and the False Face Society of the Iroquois.

Priests

performed public ceremonies for an entire group, but a medicine person usually helped only a single person or family. Unlike medicine people, priests went through long periods of formal training. They also used more equipment than the medicine people and had places of worship for performing ceremonies. Indigenous groups with priests included those of the Northeast, the Southeast, the Southwest, and Middle and South America.

Prophets.

A new type of religious leader appeared among Indigenous people after the Europeans arrived. Most of the new leaders urged their followers to give up European goods—especially liquor—and return to the old ways. Because these leaders predicted future events, the Europeans called them prophets.

Sometimes the prophets preached war to the death against white settlers. But often they called on their people to live separate, peaceful lives. Famous prophets included Hiawatha, the leader who helped form the Iroquois League in an effort to end wars between tribes; Popé, a leader of the Pueblo revolt of 1680; and the Shawnee Prophet, a brother of Tecumseh. Handsome Lake, an Iroquois prophet, founded the Longhouse religion, which combined elements of Christianity and traditional Iroquois religion. Wovoka, a Paiute, founded the Ghost Dance religion of 1890, which taught that the Creator Spirit would restore the Indigenous American world to the way it was before Europeans arrived.

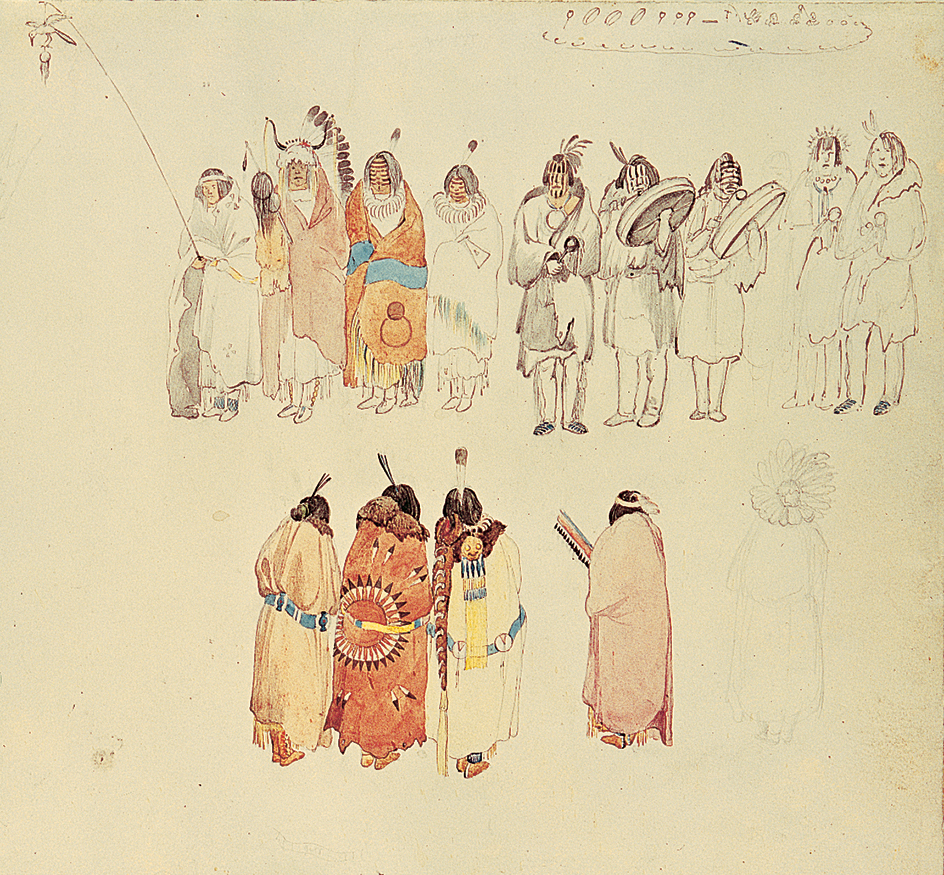

Ceremonies.

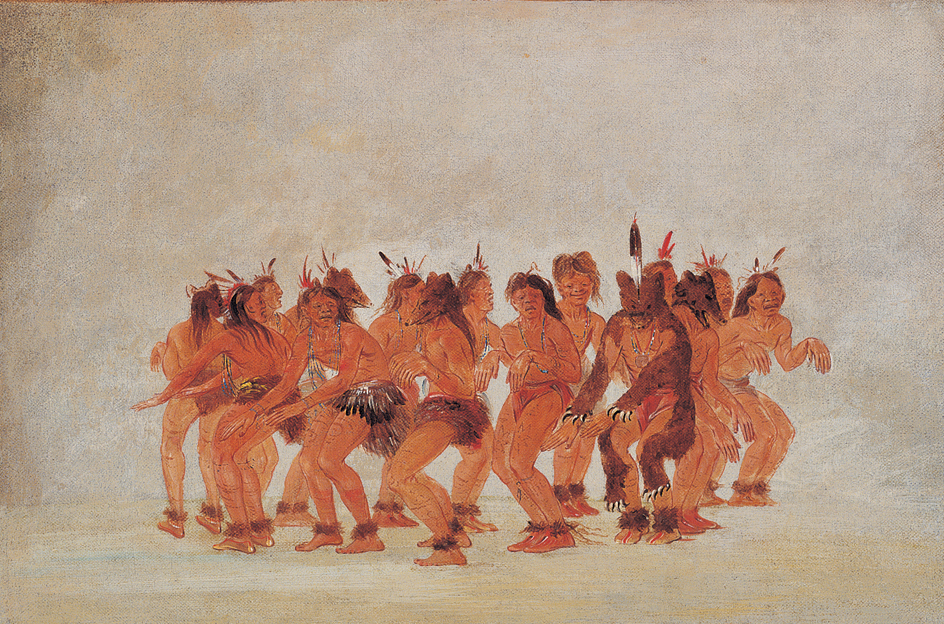

Indigenous Americans held a number of kinds of ceremonies. Many of these rituals were designed to ensure that the people had enough food. Hunting tribes performed ceremonies to keep game plentiful. The Plains peoples, for example, believed that the buffalo dance would ensure success in hunting buffalo. Farming tribes held planting ceremonies, rain dances, and harvest festivals. The green corn dance of the people of the Southeast region celebrated the summer’s first corn crop. At the end of the Hopi snake dance, snakes were released to ask the rain god to send rain.

The Pueblo people had religious societies that performed dances the year around to ensure good crops. One such group was the Kachina Society of masked dancers. These dancers also visited the homes of children to ask if the youngsters had been good. If they had not, the Kachina dancers might punish them.

The sun dance was the chief ceremony of the Plains peoples. Dancers performed it to gain supernatural power or to fulfill a vow made to a divine spirit in return for special aid. Some men tortured themselves as part of this ceremony. A sun dance lasted several days.

Nearly all Indigenous groups of North and Middle America had some kind of a sweat lodge ceremony. This ceremony took place in a structure called a sweat lodge. Some sweat lodges were heated directly by a fire. But in many lodges, water was poured over heated stones to produce steam. The hot steam caused occupants of the sweat lodge to perspire. Sweat lodge ceremonies were designed to purify the body, cure illnesses, and influence spirits.

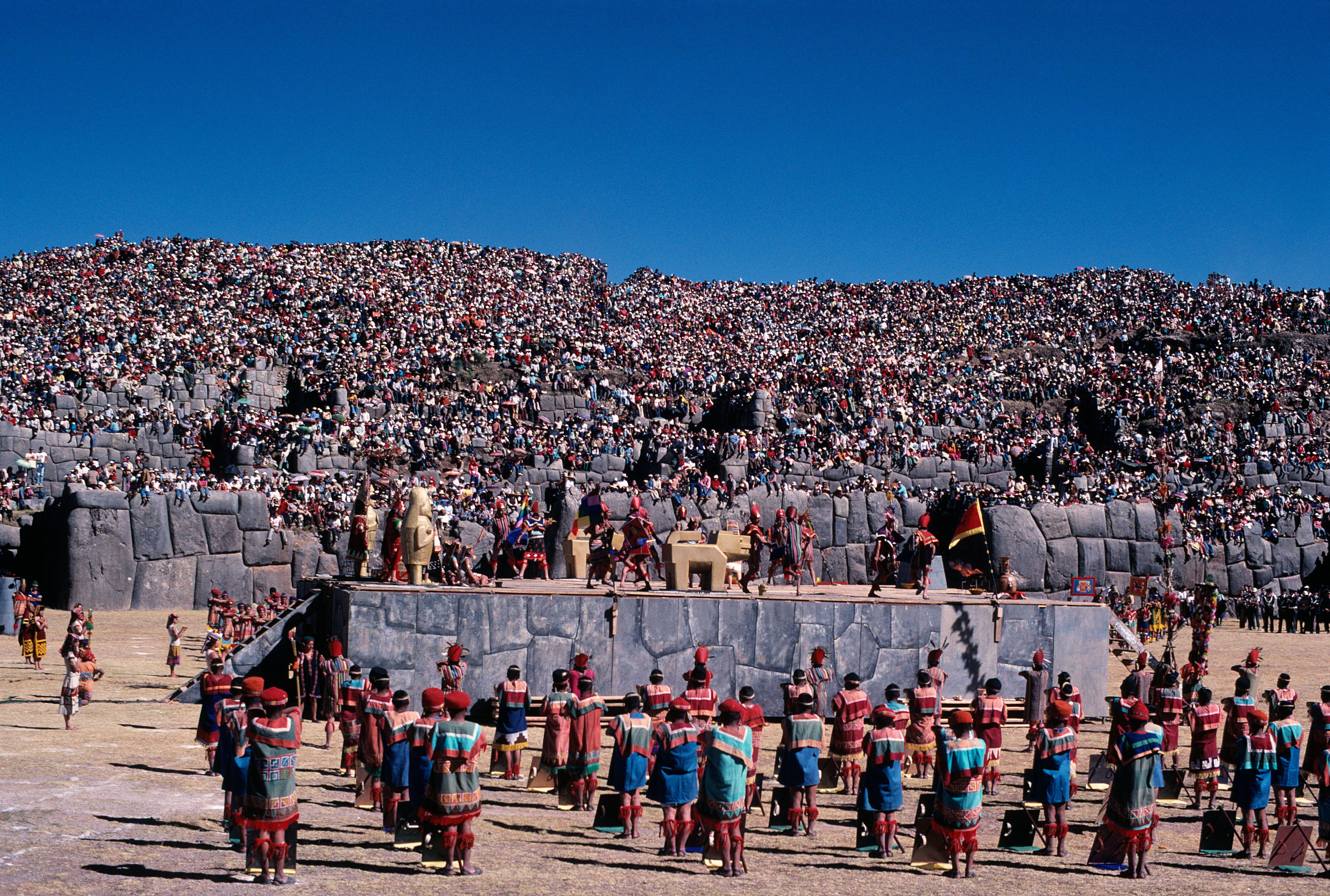

The most elaborate ceremonies were those of the Aztec and Maya in Middle America and the Inca in the Andes Mountains. Priests directed these great public celebrations. Some lasted for several days. Major Aztec ceremonies included human sacrifices to the gods.

Music

accompanied most Indigenous ceremonies. Many tribes sang to the rhythm of rattles, clappers, and drums. Some tribes also used flutes and whistles. Panpipes, a series of hollow reeds tied together, were common in the Caribbean region and in South America.

Legends

of gods, spirits, and ancestors were handed down from parent to child. Legends formed the basis of various ceremonies. Legends included stories of the world before it had people, stories of the origin of people and tribes, and tales of tribal heroes.

Trade

Trading was an important activity among nearly all Indigenous groups. The groups learned much from one another as they exchanged goods and shared ideas and experiences. Throughout the Americas, goods were traded along routes that existed thousands of years before the Europeans arrived.

In North America, obsidian was carried from the Rocky and Cascade mountains, flint from Ohio and southern Canada, copper from Lake Superior, mica from North Carolina, and shells from the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. In both North and South America, Indigenous people traded tobacco wherever it could not be grown. Salt was widely traded in agricultural areas. In Middle and South America, precious metals and gems were important items of trade.

Money.

Indigenous groups had no formal system of money. For the most part, they traded goods and services for other goods or services. In some areas, people used certain objects much as money is used today. Among the peoples of California and the Northwest Coast, sea shells called dentalia or tooth shells were divided into five sizes. The longer the shell, the greater was its value. Indigenous people of Middle America used cacao beans, from which chocolate is made, as money.

In eastern North America, Indigenous people sometimes used wampum. Wampum, a combination of purple and white beads made from shells, was strung into necklaces or belts. It served mainly as a means of keeping records or recording treaties. But because it had value, it was also used as money.

Trading centers

for various products existed only in parts of Middle and South America. These public markets had full-time traders and merchants. Among the Aztec, traders also served as spies for the government. Many lived among conquered tribes and watched for signs of revolt or nonpayment of tribute (required goods) to the Aztec.

Trade between Indigenous groups and European settlers was important in North America. The settlers needed many of the things the Indigenous people had, and Indigenous people wanted guns, horses, liquor, and metal tools. Both groups used beaver pelts and buffalo hides as items of trade in the northern areas and on the Plains.

Language

Many scholars believe the Indigenous peoples of North and South America spoke more than 2,000 languages at the time the Europeans arrived. At least 300 separate languages were spoken north of Mexico. Some had many similar words and grammar, but others differed greatly. Many Indigenous languages are lost because all the people who spoke them died before their languages could be recorded.

Language groups.

The languages of Indigenous Americans, like other languages, can be classified into large groups. In general, languages are grouped into families, which in turn are grouped into larger language phyla. One classification of Indigenous languages has 11 main phyla. These phyla are (1) American Arctic-Paleosiberian, which includes the languages of the Eskimo-Aleut family; (2) Andean Equatorial; (3) Aztec-Tanoan, which includes the Uto-Aztecan family; (4) Gê-Pano-Carib; (5) Hokan; (6) Macro-Algonquian, which includes the languages of the Algonquian and Muskogean families; (7) Macro-Chibchan; (8) Macro-Otomanguean; (9) Macro-Siouan, which includes the Iroquoian and Sioux families; (10) Na-Dene, which includes the Athabascan family of languages; and (11) Penutian.

Sometimes one language became the trade language for many tribes. For example, a waterfall at The Dalles on the Columbia River was an important trading site. The Chinook people of the area spoke for the various tribes who came there to trade. As a result, the Chinook language became a trade language. After European contact, mixtures of European and Indigenous languages began to be used for trading.

Writing.

The most highly developed Indigenous American writing systems included those of the Maya, the Aztec, and some of their neighbors in Middle America. Maya writing consisted of symbols called glyphs, which were carved in stone. The Maya also wrote on bark paper and deer hide. Scholars have translated most of the known glyphs. The Maya had a number system based on 20, and a symbol for zero. They used their numbers to create a calendar that may have been more accurate than those of the ancient Egyptians, Greeks, or Romans.

Aztec writing consisted of pictograms, most of which were pictures of objects. The Aztec used pictograms mainly to keep records. The Spaniards learned to read Aztec writing, which was still in use when they arrived. But Maya writing had not been used for several hundred years before the Europeans came.

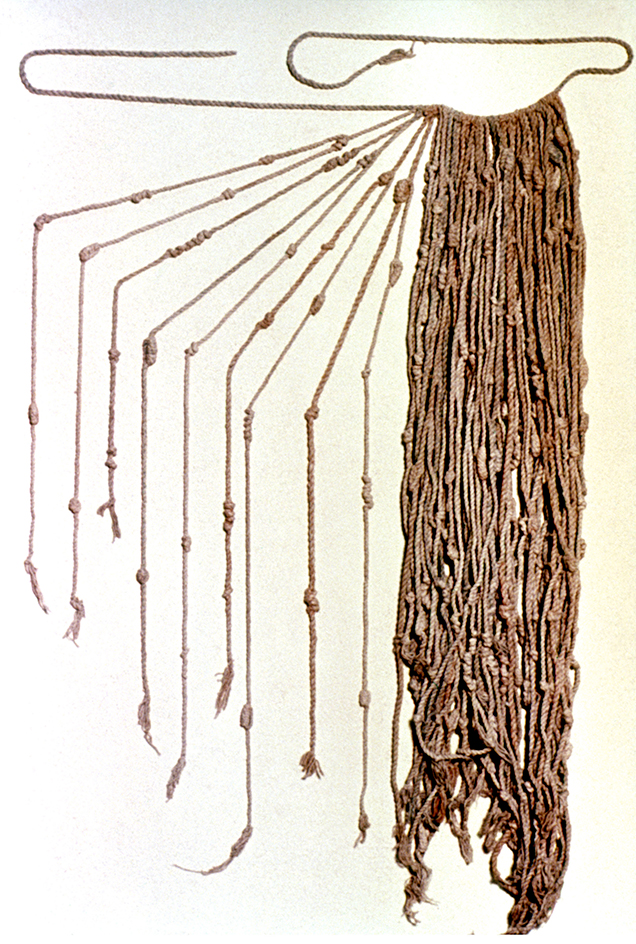

The Inca kept records by tying knots on a string called a quipu. The quipu used the decimal system. The knots at the end each stood for 1, those farther up each counted for 10, and those still higher up stood for 100. The Inca recorded crop records and population information by this method.

Some tribes used pictures or wampum to keep records. Pictures drawn on animal skins or bark showed events in a person’s life or a tribe’s history. The drawings—known to the peoples of the Plains as winter counts—also recorded the passage of time and of the seasons. Belts of wampum kept account of treaties.

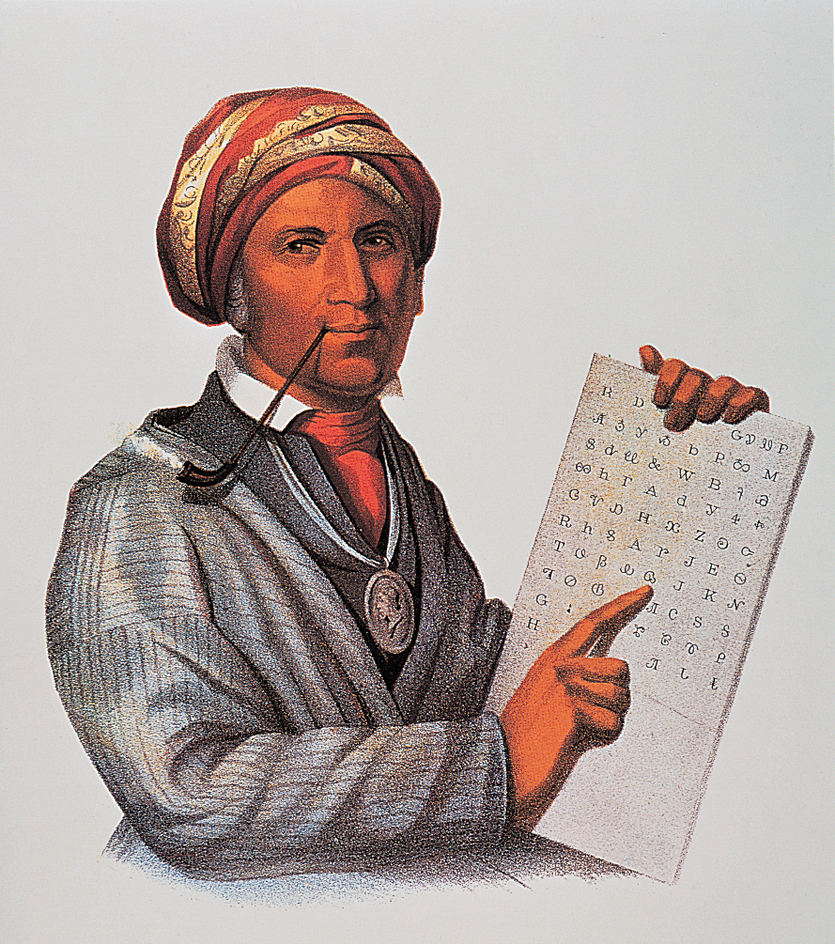

In North America, a Cherokee named Sequoyah invented a writing system called a syllabary. This system, completed in 1821, consisted of symbols that stood for sounds in the Cherokee language. With 86 signs, he could write any Cherokee word.

Other communication.

The peoples of the North American Plains spoke many languages and needed some means of communicating with one another. From this need came a series of commonly understood gestures called sign language. After the Plains people obtained horses, many more tribes came together in the region. This situation led to the further development of sign language. Sign language was not a complete language, and it could not express any complicated idea. Nor was it understood by peoples outside the Plains region.

The Plains people also used smoke signals and drum signals. However, these forms of communication could send only limited information—a warning, for example.

The first Americans

The story of the first peoples of the Americas began thousands of years ago. Scholars know little about these first Americans. Scientists have had to dig their story out of the earth itself. Pottery, stone tools, bones of human beings and animals, charcoal of campfires—all these have offered clues about how and when these early Americans lived. But many questions remain unanswered.

Scientists believe that the first peoples of the Americas are descended from the peoples of eastern Asia. In some ways, descendants of the first Americans resemble the Chinese, Japanese, and other peoples of eastern Asia in appearance. For example, they have straight black hair and high cheekbones, and little hair on their bodies. But Indigenous Americans also differ from their Asian relatives in some ways.

Early days.

For a long time, no people lived in the Americas, though many animals roamed the land. They included huge mammoths and mastodons, herds of bison and elk, and saber-toothed cats.

During the Pleistocene Epoch—between about 2.6 million and 11,500 years ago—great sheets of ice covered much of the Northern Hemisphere. These ice sheets were up to about 10,000 feet (3,000 meters) deep. The level of the oceans became lower because so much of the earth’s water made up the ice sheets. Much land that had been underwater—and is underwater again today—became dry. One such area lay between Siberia and Alaska, where the Bering Strait now separates Asia and North America by about 50 miles (80 kilometers).

Plants started to grow on the new land, and animals began to cross it in both directions, grazing on the vegetation. Some people of Siberia followed the animals that they hunted, and they crossed this land into the New World. These people were the ancestors of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. No one knows exactly when these migrants came to North America, but most experts believe they arrived at least 15,000 years ago. By about 11,500 years ago, the ice sheets had melted and the land bridge became covered with water. By 6000 B.C., people lived in nearly every part of North and South America.

The first Americans lived in small bands of 20 to 50 people. They followed herds of the animals they hunted and never settled anywhere for long. Their shelters were probably crude and temporary.

The weapons of the early Americans were mainly wooden spears with sharp stone points. Some of the points had a large flake removed from one or both sides. This type of point is called a fluted point. The first fluted point was discovered in the early 1900’s among a pile of animal bones near Folsom, New Mexico. Fluted points of that type are called Folsom points. Early hunters also used a spear-throwing device called an atlatl, which increased the range and force of their spears.

The animals hunted by the early Indigenous American peoples were very large. The hunters often found it easier to kill these beasts by driving them into swamps or over cliffs, rather than spearing them. Most of the knowledge that we have about the hunters comes from these sites where animals were killed.

The changing land.

Slowly, the climate turned warmer and wetter, and the huge ice sheets began to melt. Water from the ice sheets flowed into riverbeds and lakes, and raised the level of the oceans. The land across the Bering Strait became covered with water, and migration to the New World all but stopped.

The large animals hunted by early Indigenous Americans began to die out about this time. No one knows exactly why, but the animals’ food supply of grass may have slowly decreased as the climate changed.

A change in Indigenous ways of life accompanied the changing climate and plant and animal life. In North America, great forests replaced many grasslands in the north and east. Small, swift animals lived in these woodlands. Indigenous hunters may have begun to use the bow and arrow at this time. It made a good weapon for hunting swift woodland animals. Around the lakes and along the rivers, people began to fish and to trap ducks and other water birds. They gathered shellfish for food along the coasts of both North and South America.

Some regions became desertlike. Indigenous people who lived in these areas ate more plant food because the animals were small and scarce. The desert people ground seeds to make flour, gathered berries and bulbs, and ate nuts. Sometimes they added meat to their diet—chiefly rabbits, prairie dogs, and an occasional deer.

The first farmers.

In what is now Mexico, the warm, dry climate produced a way of life similar to that of other desert areas—with one important difference. The people began to cultivate certain grasses that became the ancestors of modern corn. By 1500 B.C., Indigenous Mexican peoples had improved the quality of corn until it grew as large ears. Corn, along with beans and squash, became their main source of food. These people no longer had to travel in search of food, and they began to settle in villages. With farming, the land could support more people. They could build more permanent houses and towns, and have more time for arts and crafts and religious ceremonies. Monte Albán, Teotihuacán << tay oh `tee` wah KAHN >>, and other large cities developed.

Farming spread both north and south from Mexico. In Middle America and the Andean Highlands, the Aztec, Maya, and Inca achieved the most complicated societies in the New World. As the peoples of North America learned farming, their villages grew larger. Farming along the Ohio and Mississippi rivers became so productive that villages developed into towns and cities. Between about 100 B.C. and A.D. 500, in Ohio, the Hopewell people built huge burial mounds and ceremonial centers. Along the Mississippi and other major rivers, from about 700 to 1700, some cities grew to great size.

Estimates of the Indigenous population of the New World when Columbus arrived vary. Many scholars estimate that there may have been between 30 million and 75 million Indigenous people living in all of North and South America, with about 2 million to 7 million of these people living in North America north of Mexico. But some estimates run as high as 118 million for the Americas, with about 18 million living north of Mexico.

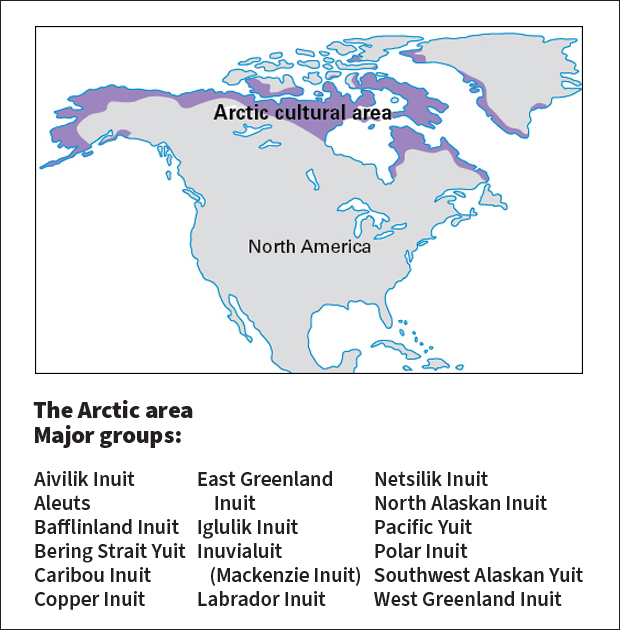

Peoples of the Arctic

In North America, the Arctic includes most of the seacoast of Greenland, northern Canada, and Alaska. The land consists mainly of tundra. In the winter, ice and snow cover the ground, and most of the Arctic Ocean is covered with ice.

Scholars classify the Indigenous peoples of the North American Arctic into three large groups: (1) the Aleuts, who live on the Aleutian Islands off the coast of mainland Alaska; (2) the Inuit, who live from northern Alaska across Canada to Greenland; and (3) the Yuit, who live in western and southern Alaska, as well as in Siberia, in Russia. The three groups have similar ways of life, but their languages, though related, differ.

Arctic peoples probably began to migrate across the Bering Strait into the New World about 10,000 years ago. They were the last prehistoric people to arrive in the Western Hemisphere. They are more closely related to peoples who currently live in Siberia than they are to Indigenous Americans south of the Arctic.

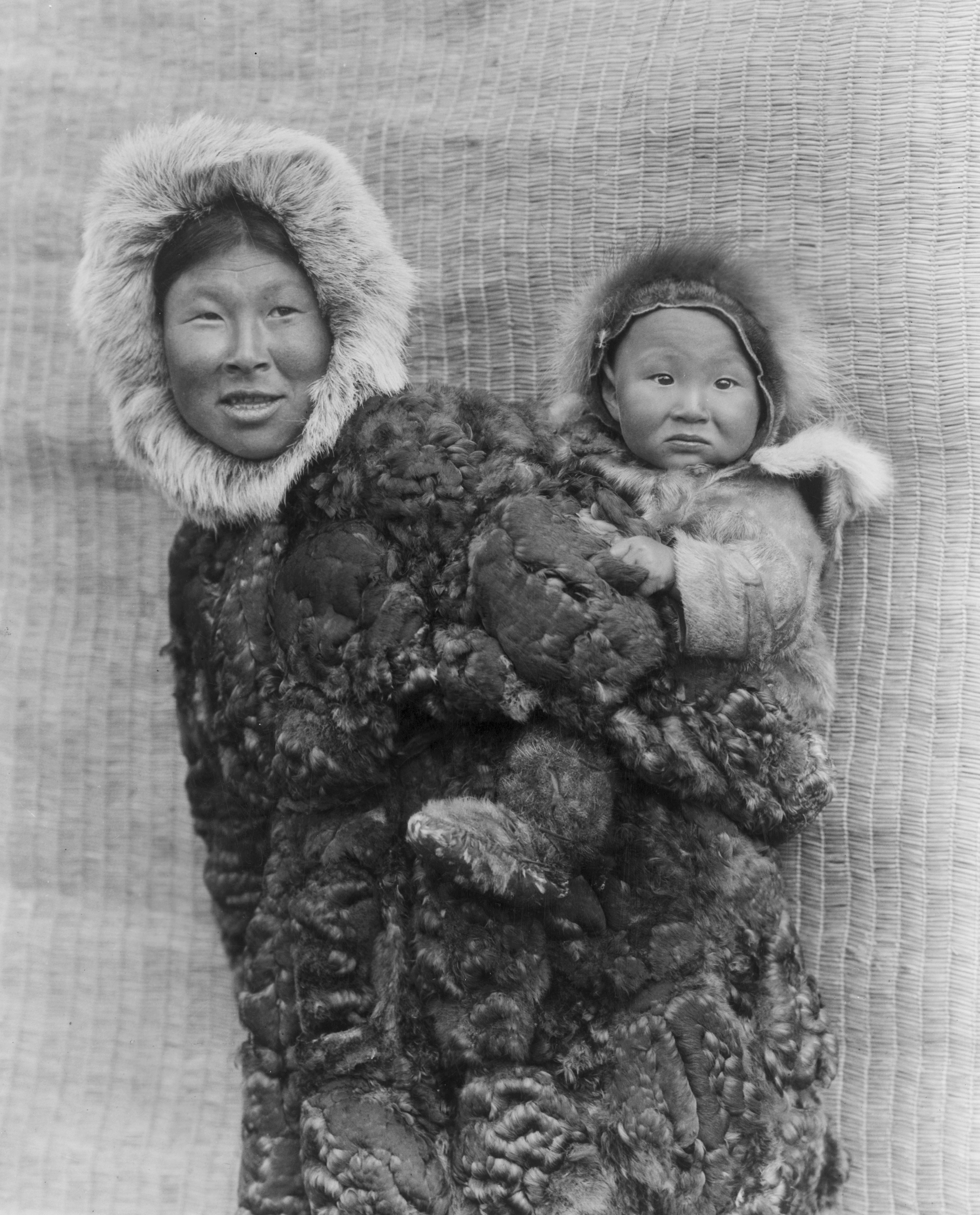

Before European contact.

Most Arctic peoples lived in small bands, mainly in widely scattered settlements along the seacoast. The bands moved often in search of food but usually remained within a certain territory. Most Inuit bands did not have permanent leaders. Many Aleut and Yuit villages had chiefs.

Arctic peoples obtained food mainly by hunting and fishing. Seals were the primary food across most of the region. Sealskin was widely used for making shelters and boats, clothes, tools, and other goods. Arctic peoples also hunted a type of deer called caribou and whales, walruses, and other sea mammals for their skin and for food. In much of the Arctic, meat was eaten raw because there was no firewood.

Men, women, and children of the Arctic wore similar clothing. They usually wore a caribou-skin parka (hooded jacket) and trousers and sealskin boots. Babies and young children often rode in the backs or hoods of their mothers’ parkas.

In Alaska and Greenland, many shelters were made of wood, sod, stone, or animal skins. In much of Alaska, forests provided wood for making permanent houses. Some Inuit in Canada built snowhouses during the winter, but they lived in skin tents during the summer.

The Inuit used skin boats for travel and to hunt sea mammals. These boats were made of sealskin or walrus skin stretched over a wooden frame. In the winter, Arctic peoples often traveled across the frozen sea and the frigid land on dog sleds.

Weapons of the Arctic peoples included harpoons, spears, bows and arrows, and knives. Bones and antlers were often used to make arrowheads and spear points.

Arctic peoples believed the animals, mountains, sea, and other things around them each had a spirit. Shamans were thought to have some control over the spirit world. When hunters killed an animal for food, they thanked its spirit.

After European contact.

The Inuit in Greenland came into contact with Vikings about 1,000 years ago. Beginning in the 1500’s, European explorers met the Inuit of northeastern North America. Aleuts and the Yuit of Alaska first met Russian and other European explorers, traders, and colonists in the 1700’s.

Contact between European and Arctic peoples increased during the 1800’s as whaling and the fur trade grew in the region. Rifles obtained from white people enabled Arctic peoples to hunt more efficiently but also eventually led to a scarcity of game animals. Today, the peoples of the Arctic have adapted to the modern world while preserving much of their traditional way of life.

For more information on the peoples of the Arctic, see Aleuts and Inuit.

Peoples of the Subarctic

The Subarctic is a large semiarctic region that includes the interior of Alaska and most of Canada. It is a land of cold winters and heavy snows. The Subarctic has many lakes and streams, and forests of fir, pine, spruce, and other evergreen trees.

Before European contact.

The Subarctic was one of the most thinly populated regions of North America. The people who lived in this rugged region belonged to one of two major language groups—the Algonquian speakers in the east and the Athabascan speakers in the west. In spite of their language differences, the two groups had similar ways of life.

Subarctic peoples lived in much the same way as did the first peoples to migrate from Asia to the New World. Tribes consisted of many small bands. Each band lived in its own territory but was related through marriage to other bands in the tribe. Many groups in the east traced family ties through the father. Subarctic peoples in the west generally traced ancestry through the mother. Most tribes did not have permanent leaders.

Food was often scarce, and the people moved about hunting and gathering wild plants, berries, and nuts. The growing season was too short for farming. Buffalo, caribou, deer, elk, moose, and musk ox were the main animals hunted. Fish and shellfish were important foods along the coasts, rivers, and lakes of the region.

Peoples of the Subarctic made most of their utensils of wood. They made containers but no pottery. In the east, containers were fashioned from bark, and in the west they were made of woven spruce roots.

Subarctic tribes used caribou or moose skin to make most of their clothing. The men wore long shirts, breechcloths, leggings, and moccasins. The women had about the same clothing but wore longer shirts and shorter leggings. In winter, everyone wore robes, mittens, and fur caps for extra warmth. People decorated many of their garments with quillwork, embroidery, or painted designs.

Houses were made of wooden frames covered with bark, brush, or animal skins. The people also built dome-shaped wigwams, lean-tos, and sturdy log houses. Families that moved around a lot lived in tipis.

In summer, the people of the Subarctic used bark canoes to travel on the lakes, rivers, and streams in search of food. In winter, they used wooden toboggans and snowshoes for travel.

Weapons of the Subarctic included bows and arrows, spears, clubs, and knives. In the east, the tribes used stone to make arrow points and knife blades. The western tribes generally used bone and antlers to make tools, and beaver teeth for making knives. Wars were almost unknown.

After European contact.

Indigenous Americans of the Subarctic usually had good relations with the early French fur traders. But the tribes slowly changed their way of life by hunting fur-bearing animals that they traded to the French for weapons, traps, and food. Previously, they had made most of the necessities of life from various parts of the animals they killed.

Indigenous groups took sides in the wars between the French and English colonies. Some fought for the French and some for the English. The tribes also fought one another as a result of competition for the fur trade. Eventually, the Indigenous people lost their land to the settlers. Today, most Indigenous people of the Subarctic region live in areas set aside for them, called reserves in Canada and reservations in the United States.

Peoples of the Northeast

The Northeast cultural area extends from just north of the Canadian border to just south of the Ohio River. It stretches from the Atlantic Ocean, including the coasts of Virginia and northern North Carolina, to about the Mississippi River. The Northeast is a region of cold winters and warm summers. Forests cover much of the area, which is often called the Eastern Woodlands. Rolling prairies lie in the west.

Before European contact.

Almost all the Northeast tribes spoke an Iroquoian or Algonquian language. The Iroquoian-speaking tribes included the Cayuga, Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, and Seneca. By the early 1600’s, these five groups had joined together to form the Iroquois League. The Tuscarora joined the league in the early 1720’s. The Huron also spoke an Iroquoian language, but they were enemies of the league.

The Iroquois lived mostly by growing corn, beans, and squash. Slash-and-burn agriculture was the main method of farming. The women farmed and gathered wild plants, nuts, and berries. Men hunted and fished.

Among the speakers of Algonquian languages were the Abenaki in the east and the Ojibwe in the west. Some of the northernmost groups depended more on hunting, gathering, and fishing than on farming. But most Algonquian groups grew corn, beans, squash, and other crops. The Ojibwe and other peoples of the Great Lakes region also harvested wild rice. Some tribes collected the sap of maple trees.

Houses were made to protect people from the cold in winter. Most Northeastern people lived in villages of dome-shaped wigwams covered with bark. Iroquois villages included longhouses with separate sections for related families. Tall fences called palisades surrounded many villages and provided protection from enemies.

The peoples of the Eastern Woodlands traveled on foot or in bark canoes. Northeastern people made deerskin shirts, dresses, leggings, and breechcloths. Many of these people rubbed their hair with bear grease to make it smooth and shiny. In some groups, men shaved their heads almost completely, leaving only a small tuft of hair on top.

Warfare sometimes broke out among the peoples of the Northeastern region. Weapons included clubs and bows and arrows. The Iroquois were the dominant group in warfare.

Family ties were traced through the father among most Algonquian speakers. Among the Iroquoian speakers and a few Algonquian speakers, however, family ties were traced through the mother. Many Iroquois longhouses sheltered an elderly couple with separate “apartments” for each married daughter. The couple’s married sons lived in the longhouses of their wives’ families.

Leaders of the Eastern Woodlands tribes were called sachems. The five tribes that formed the Iroquois League chose 50 sachems to lead their federation. The sachems were chosen from different clans. Only men could be sachems, but only women had the right to select who became a sachem. If a sachem did not do what the women wanted in council, they could remove him and select a new leader.

When councils of the Iroquois League met, they made decisions by consensus. Sachems would give speeches setting forth their position on an issue. Discussions sometimes went on for hours or days until everyone could compromise and agree on the same plan.

Religion played an important part in the lives of the peoples of the Northeast. These tribes believed in a spirit power that inhabited many creatures and forces of nature and could appear in visions as guardian spirits. In some Algonquian languages, this power was called manito. Medicine people supposedly could summon helper spirits to cure diseases or to predict who would win a war.

Complicated ceremonies were common in the Great Lakes region. The Ojibwe, Ho-Chunk, and neighboring tribes had a secret society called the Midewiwin Society. Its members had special songs, rites, and equipment that they used to reach the gods. Some groups, including the Shawnee, Kickapoo, and Potawatomi, made use of medicine bundles—bags of such objects as animal skins, pipes, dried herbs, and tobacco. Medicine bundles, sometimes known as sacred bundles, were believed to have special powers, and they were opened only during certain ceremonies. The members of the Iroquois False Face Society wore brightly painted wooden masks during their disease-curing rituals.

After European contact.

The tribes of the Eastern Woodlands were among the first to meet European explorers and settlers. At first, the two groups had friendly relations. Squanto, a Patuxet, is said to have taught the white settlers how to plant corn and fertilize it with dead fish. Massasoit of the Wampanoag helped the Pilgrims of Plymouth Colony. In 1621, the Wampanoag and Pilgrims joined in a Thanksgiving ceremony to give thanks for a good harvest and peace. But the friendly relations did not last, and warfare soon became common. Most of the early fighting consisted of small battles between settlers and Indigenous people. Smallpox, measles, and other European diseases killed many Indigenous people.

As the settlers moved westward, they took the land for their own. When Indigenous groups objected, fighting broke out. Some of these battles grew into wars. The Indigenous peoples of the Northeast also became involved in the wars between France and Britain for possession of North America. Indigenous tribes took sides in these wars and often ended up fighting each other as well as the white settlers. The Huron and many Algonquian groups sided with the French. The tribes of the mighty Iroquois League generally allied themselves with the British and helped Britain gain control of almost all of France’s territory in North America.

The Iroquois League began to split during the American Revolution (1775-1783). Some members of the league sided with the American colonists, but most supported the British or remained neutral. After the American victory, white settlers poured onto Iroquois lands. Weakened by diseases and conquest, the league fell apart.

Farther west, the Shawnee leader Tecumseh united many of the tribes of the Northeast and Southeast. The Shawnee and some other groups sided with the British during the War of 1812 in an attempt to push the American settlers off their lands. But large-scale resistance ended shortly after Tecumseh was killed in the Battle of the Thames in 1813.

Many tribes from the Eastern Woodlands now live in Oklahoma and various Western states. The U.S. government forced them to move to these areas during the early 1800’s. But the Iroquois and some others still live on their original lands. Many Iroquois became leaders in the struggle for the rights of Indigenous people in Canada and the United States.

Peoples of the Southeast

The Southeast extends from just south of the Ohio River to the Gulf of Mexico and from the Atlantic Coast of southern North Carolina to just west of the Mississippi River. It is a region of mild winters and warm, humid summers. The terrain varies from the mountains of the Appalachians to the sandy coastal plain, with rolling hills and some swamps in-between. Pine forests cover most of the region.

Before European contact.

The tribes of the Southeast included the Catawba, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee, and Seminole. The Muscogee, Alabama, Coushatta, and a number of other tribes belonged to a federation that European Americans called the Creek Confederacy. Southeastern peoples spoke many languages, including ones belonging to the Algonquian, Muskogean, and Siouan language families.

Southeastern peoples generally had an abundant supply of food. The adequate rainfall and long growing season enabled them to grow large quantities of corn. A favorite drink or soup was sofkee, which was made by grinding and then boiling corn. The people of the Southeast also grew beans, squash, pumpkins, and sunflower seeds, and raised turkeys. The women farmed and gathered nuts, berries, and wild plants. Men cleared the land and did most of the hunting and fishing.

People of the Southeast traveled either on foot or in wooden dugout canoes. Dugout canoes were made by burning out the centers of fallen trees with embers and then chopping out the charred wood with stone axes.

Most Southeastern villages had a central plaza with a council house, a public square, and a ceremonial ground. Most houses were made of wattle and daub—that is, a wooden frame covered by reed mats with plaster spread over them. Palisades enclosed many villages.

The people of the Southeast made deerskin shirts, dresses, leggings, and breechcloths. Women sometimes wore wraparound skirts of woven cloth made of plant fibers. Turkey feathers were sewed onto netting to make robes. Inhabitants of warmer areas wore little clothing, and many decorated their bodies with tattoos and body painting. Muscogee and Chickasaw men shaved their heads almost completely, leaving only a small tuft of hair on top. Choctaw men let their hair grow long.

Warfare sometimes broke out among peoples of the Southeast area. Weapons included bows and arrows and a variety of clubs. Warriors fought for glory and often tattooed their bodies with signs of brave deeds. Elaborate ceremonies accompanied most warfare. Before battle, the warriors gathered in a council house. They painted themselves, performed religious rites, and took special medicines. Sometimes, two tribes would play a stickball game to settle a dispute and thereby avoid a war.

Women had much power and influence among most Southeastern groups. In most cases, family ties were traced through the mother, and extended families in which all the women were related formed the basic social unit. Cherokee women could attain the position of war woman and participate in war councils. A few Cherokee women fought as warriors.

The Southeast had the most complex forms of government north of present-day Mexico. The Natchez people had a king called the Great Sun. He and his family formed the highest class, the Suns. Below them were two other upper classes, the Nobles and the Honored Men and Women. At the bottom were the commoners. The Natchez built temples and the Great Sun’s house on large, flat-topped, earthen mounds.

Many Southeastern tribes had ascending ranks of chiefs. Nearly all chiefs were men. A chief could head a village or a whole region of villages or, in the case of a chiefdom, a whole tribe. Typically, some chiefs represented the peace faction. Others represented the war faction. Councils of assistants, advisers, and shamans helped each chief. In most cases, a man inherited his position of chief from his mother’s brother, not from his own father.

Religion played an important role in the lives of the peoples of the Southeast. The people honored their ancestors and held elaborate funeral ceremonies. Many of the dead were buried with grave goods—that is, pottery and other objects—for use in the afterlife. A number of groups worshiped the sun.

The green corn dance was the most important ceremony of the Southeastern peoples. This annual harvest celebration lasted several days and served as a time for giving thanks. The dance was thought to maintain harmony and to make things pure again. A new year began when a community fire was lit during the ceremony and a woman from each household took some fire for her hearth.

After European contact.

The tribes of the Southeast were among the first Indigenous Americans to meet European explorers and settlers. Armies, explorers, missionaries, and traders from Europe came through the Southeast looking for gold, fur, people to enslave or to convert to Christianity, and even the Fountain of Youth. As the Europeans took the land for their own, Southeastern peoples objected. Warfare between the two groups became common, and many Indigenous people were killed. Many also died from measles, smallpox, and other diseases brought by Europeans.

After the American Revolution, the Cherokee and some other Southeastern peoples tried to adopt the ways of white Americans. They began to dress, speak, and act like whites. White people sometimes called the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole the Five Civilized Tribes because white people considered their own ways more civilized than Indigenous customs.

However, white Americans continued to desire the lands of the Southeastern tribes. In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act. This legislation allowed the U.S. government to move Indigenous people living east of the Mississippi River to a territory west of the river. Thousands of people died during this forced removal to the West, and the Cherokee came to refer to their westward journey as the Trail of Tears. This term was later applied to the forced removal of other Southeastern tribes as well. In some cases, a small part of a tribe managed to remain behind in the East. A small group of Cherokee, for example, fled to the mountains of North Carolina. Today, the tribes that remain in the Southeast try to maintain a balance between traditional and modern ways of life.

Peoples of the Plains

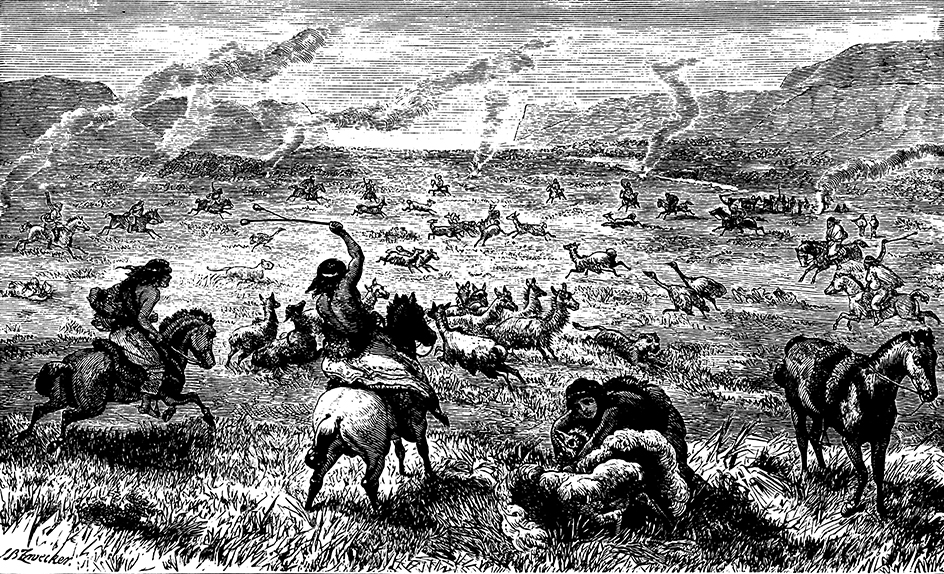

The Plains stretch from just west of the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains and from Canada to Mexico. Few people lived in this vast grassland region before the arrival of the Europeans. But after the Spaniards brought the horse to the region in the 1600’s, a new way of life appeared on the Plains. On horseback, the Plains peoples could follow the great herds of buffalo. After new tribes and white settlers arrived on the Plains, fighting broke out.

Before European contact.

Most of the original Plains tribes lived in villages along the rivers and streams where the land was fertile and easily cultivated. Out on the grasslands, the tough sod was hard to farm. The women tended crops of beans, corn, squash, and tobacco while the men hunted deer, elk, and sometimes buffalo. During the summer, people left their villages to hunt the vast buffalo herds on the Plains. The huge beasts were difficult to hunt on foot, and so the men tried to stampede herds of them off cliffs or into areas where they could be killed more easily. In the fall, the Plains people returned to the villages and harvested their crops. They pulled the slain buffalo home on travois, which were made by fastening a platform to two poles. Sometimes the people used dogs to pull the travois.

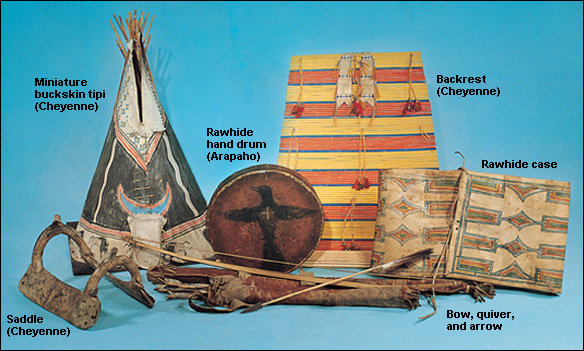

The early Plains peoples wore deerskin breechcloths, leggings, and simple shirts. They used buffalo hides for winter robes and moccasin soles. In their villages, the tribes lived in earth lodges, frames of logs covered with brush and dirt. Out on the Plains, they lived in tipis made of animal skins.

After European contact.

The coming of the horse and gun greatly changed life on the Plains. With the horse, hunters could leave their villages and follow the buffalo herds—which they could not do on foot. Buffalo meat became their main food. The flesh could be roasted over a fire, dried in the sun to make jerky, or pounded with berries and suet to make pemmican. The Plains people used buffalo skins to make clothing, bedding, and tipis. They made the bones and horns into tools and utensils and used dry buffalo manure for fuel. The tribes held many ceremonies aimed at assuring a large enough supply of buffalo.

The tribes on the eastern Plains, sometimes called the Prairies, continued to farm part of the year and to live in earth lodges. But on the western Plains, often referred to as the true plains, daily life became centered on the vast buffalo herds. The buffalo hunters stayed on the move continually. As a result, large tipis, which could be moved from camp to camp, replaced earth lodges as the principal dwellings on the true plains. The people used horses to haul their possessions on large travois. A good buffalo hunter might have two or more wives to prepare all the buffalo hides he brought home.

Nearby tribes, and those forced westward by the advancing white people, quickly adopted the Plains way of life. These late arrivals on the Plains included the Arapaho, Blackfeet, Cheyenne, Comanche, and Lakota.

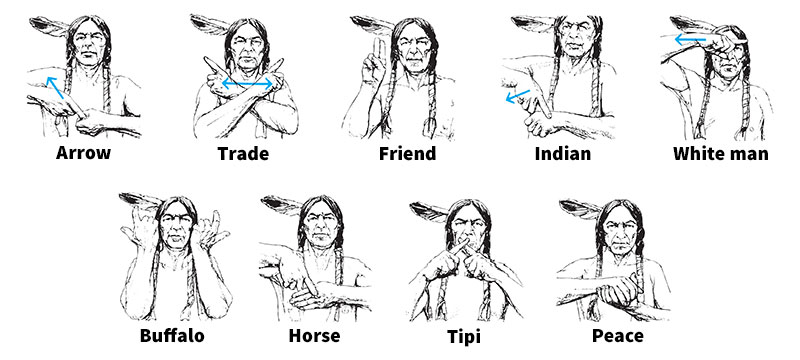

With many new tribes on the Plains, communication required some kind of common, easily understood language. This need led to the development of the Plains sign language.

The increasing number of tribes on the Plains fought with one another and with white people. Success in warfare earned fame for a warrior. Counting coup—that is, the act of touching a live enemy and getting away from him—won the highest honor. After battle, the warriors told of their heroic deeds and celebrated their victory. Eagle feathers were awarded for bravery.

The religion of the Plains peoples centered on spiritual power. Almost every man and some women had a personal guardian spirit that they had seen during a vision quest. Tribes also had medicine bundles containing plants, stones, and other objects with supposed supernatural powers. The most important ceremony was the sun dance.

The widespread killing of buffalo, particularly by white hunters, threatened to wipe out the great beasts. By 1890, the buffalo herds had almost disappeared—and with them, the Plains way of life. In their place came increasing numbers of ranchers and settlers who turned the Plains into cattle ranches and homesteads. The federal government moved many tribes onto reservations and hoped they would take up farming. But the Plains peoples considered farming to be the work of women or white people. They turned instead to warfare and, later, to religious movements. One such movement was the Ghost Dance religion, led by Wovoka of the Paiutes. Some adherents believed that it would bring back the buffalo and remove the settlers from Indigenous lands.

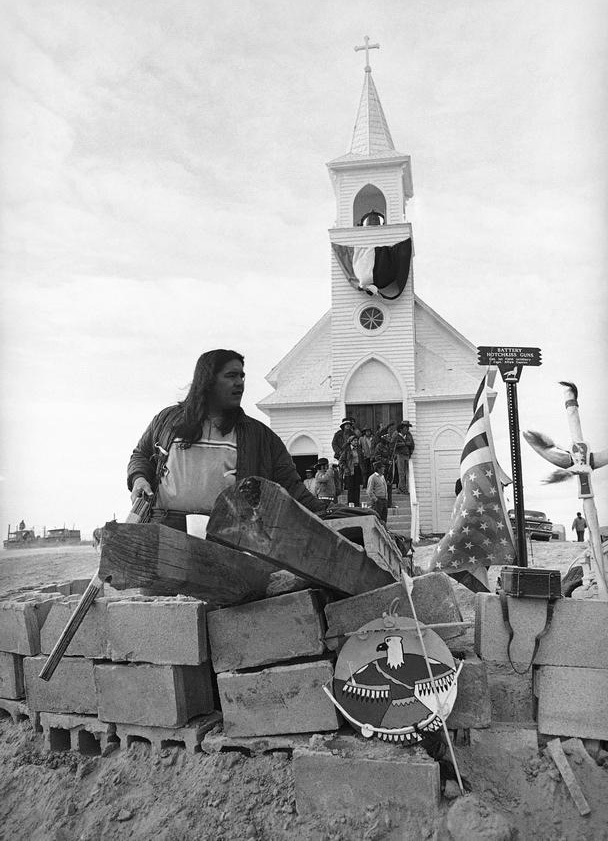

The last major conflict between Plains peoples and the U.S. Army took place in 1890. Federal troops trapped and massacred as many as 300 Sioux men, women, and children at Wounded Knee in South Dakota.

Today, many Indigenous peoples of the Plains still perform the sun dance and other traditional ceremonies. In addition, the Cheyenne and Comanche in particular have become leaders in the Native American Church. Some Sioux became well known for their activities in the American Indian Movement (AIM), a civil rights and treaty rights organization.

Peoples of the Northwest Coast

The Northwest Coast stretches along the Pacific Ocean from southern Alaska to northern California. Fish and seafood are plentiful in the ocean and the rivers of the region. Thick forests rise sharply from the beaches and include giant redwoods, Douglas-firs, and pine trees. The region has a mild, humid climate.

Before European contact.

Among tribes of the Northwest Coast, a few families had great influence in each village because of their ancestry and wealth. People in the north traced family ties through the mother; those in the south, through the father. Tribes measured wealth in terms of such possessions as canoes and blankets. Other valuable property included enslaved people—captured members of enemy groups or their descendants. But sheets of copper, hammered into shield shapes, had the greatest value of all. These sheets are sometimes called coppers.

Men—and some women—of wealth and social position proved their right to high rank at a feast called a potlatch. During a potlatch, which lasted several days, a host fed the guests and gave away many valuable items. The gifts gained respect for the host and the host’s clan and indicated the social rank of the individuals who received the gifts. Some potlatches were held to mark births, marriages, and deaths. During rival potlatches, hosts destroyed a valuable copper shield to challenge their rivals to outdo them at another potlatch.

Food from the sea included not only salmon and a variety of fish, but also seals, sea otters, sea lions, whales, and other animals. Plentiful land animals included bear, caribou, deer, elk, and moose.

The Northwest Coast tribes made elaborate boxes, masks, grave markers, and utensils from wood. They built houses with large posts and beams, covered with planked sides and gabled roofs. Several families lived in one of these large structures.

Great seagoing canoes—some more than 60 feet (18 meters) long—were burned and cut from the trunks of huge cedar and redwood trees. The canoes could hold as many as 60 people. The people carved or painted designs on many of these vessels.