Industrial Revolution. During the late 1700’s and early 1800’s, great changes took place in the lives and work of people in several parts of the Western world. These changes resulted from the development of industrialization. The term Industrial Revolution refers both to the changes that occurred and to the period itself.

The Industrial Revolution began in Britain (a country now known as the United Kingdom) during the late 1700’s. It started spreading to other parts of Europe and to North America in the early 1800’s. By the mid-1800’s, industrialization was widespread in western Europe and the northeastern United States.

The introduction of power-driven machinery and the development of factory organization during the Industrial Revolution created an enormous increase in the production of goods. Before the revolution, manufacturing was done by hand, or by using animal power or simple machines. Most people worked at home in rural areas. A few worked in shops in towns and belonged to associations called guilds. The Industrial Revolution eventually took manufacturing out of the home and workshop. Power-driven machines replaced handwork, and factories developed as the most economical way of bringing together the machines and the workers to operate them.

As the Industrial Revolution grew, private investors and financial institutions provided money for the further expansion of industrialization. Financiers and banks thus became as important as industrialists and factories in the growth of the revolution. For the first time in European history, wealthy business leaders called capitalists took over the control and organization of manufacturing.

Historians have disagreed about the overall effect of the Industrial Revolution on people’s lives. Some historians have emphasized that the revolution greatly increased the production of goods. They argue that this increase did more to raise people’s standard of living after 1850 than all the actions of legislatures and trade unions. Other historians have stressed the negative effects of the revolution. They point to the overcrowded and unsanitary housing and the poor working conditions created by rapid industrialization in the cities. Most historians now believe that factory conditions and worker wages were terrible before 1850 but improved after that date. These improvements led to an increase in life expectancy for workers.

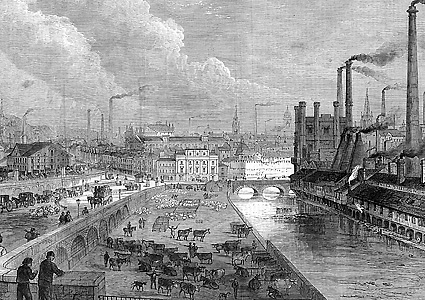

Most historians agree that the Industrial Revolution was a great turning point in the history of the world. It changed the Western world from a basically rural and agricultural society to a basically urban and industrial society. Industrialization brought many material benefits, but it also created a large number of problems that remain critical in the modern world. For example, most industrial countries face problems of air, land, and water pollution.

Life before the Industrial Revolution

On the eve of the Industrial Revolution, less than 10 percent of the people of Europe lived in cities. The rest lived in small towns and villages scattered across the countryside. These people spent most of their working day farming. Unless they could sell surplus food in nearby towns, they grew little more than they needed for themselves. The people in rural areas made most of their own clothing, furniture, and tools from raw materials produced on the farms or in forests.

Before the Industrial Revolution, some industry existed throughout western Europe. A little manufacturing took place in guild shops in towns. Craftworkers in the shops worked with simple tools to make such products as cloth, hardware, jewelry, leather goods, silverware, and weapons. Some products made in the towns were exchanged for food raised in the countryside. Town products were also exported to pay for luxuries imported from abroad, or they were sent to the colonies in payment for raw materials.

Most manufacturing, however, took place in homes in rural areas. Merchants called entrepreneurs distributed raw materials to workers in their homes and collected the finished products. In most places, the entrepreneurs owned the raw materials, paid for the work, and took the risk of finding a market for their products. They often spread their operations to nearby villages. In the home, the whole family worked together making clothing, food products, textiles, and wood products. Workers themselves provided most of the power for manufacturing. Water wheels furnished some power.

The way of life differed from place to place, depending on the climate, the soil, and the distance from towns and trade routes. For most people, life revolved around the agricultural seasons—planting, cultivating, harvesting, and processing the harvest. The way of life changed little from one generation to the next, and most sons followed their father’s trade.

Life was hard for most people. They lived under the constant threat that their crops might fail. Although few people starved, many of them suffered from malnutrition. As a result, they caught diseases readily, and epidemics were common. Most workers produced little and earned little. Only a few people enjoyed large incomes, usually because they owned inherited land, held public office, or had succeeded in business. Little money was saved or invested in business ventures. Outside of cities, there were few opportunities for investment.

Before the Industrial Revolution, powerful monarchs ruled most European countries. Great landowners, rich merchants, and some members of the clergy also had considerable political influence. But the workers and farmers had no voice in the government. Many countries did not even hold elections. Although Britain had a Parliament, only men who paid a certain amount of taxes could vote. A handful of voters often determined who would represent a district in Britain. All these social, economic, and political conditions changed in Britain as the Industrial Revolution developed.

Growth of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution began in Britain for several reasons. The country had large deposits of coal and iron, the two natural resources on which early industrialization largely depended. Other industrial raw materials came from the various colonies of Britain. By the late 1700’s, the country had become the world’s leading colonial power. British colonies provided raw materials as well as markets for manufactured products. These colonial markets helped stimulate the textile and iron industries, which were probably the two most important industries during the Industrial Revolution.

In addition, Britain’s scientific culture emphasized practical application and invention. For example, this culture helped make it possible for James Watt, a Scottish engineer, to make great improvements in the operation of the steam engine.

The demand for British goods grew rapidly during the late 1700’s both at home and abroad. This demand forced businesses to compete with one another for the limited supply of labor and raw materials, which raised production costs. The rising costs of production began to cut into profits. Further demand could not be satisfied until Britain enlarged its capacity to produce goods inexpensively.

British merchants did not want to raise the prices of their goods and thus discourage demand. They sought more economical and efficient ways of using capital and labor so the amount each worker produced would increase faster than the cost of production. The merchants achieved their goal through the development of factories, machines, and technical skills.

The textile industry.

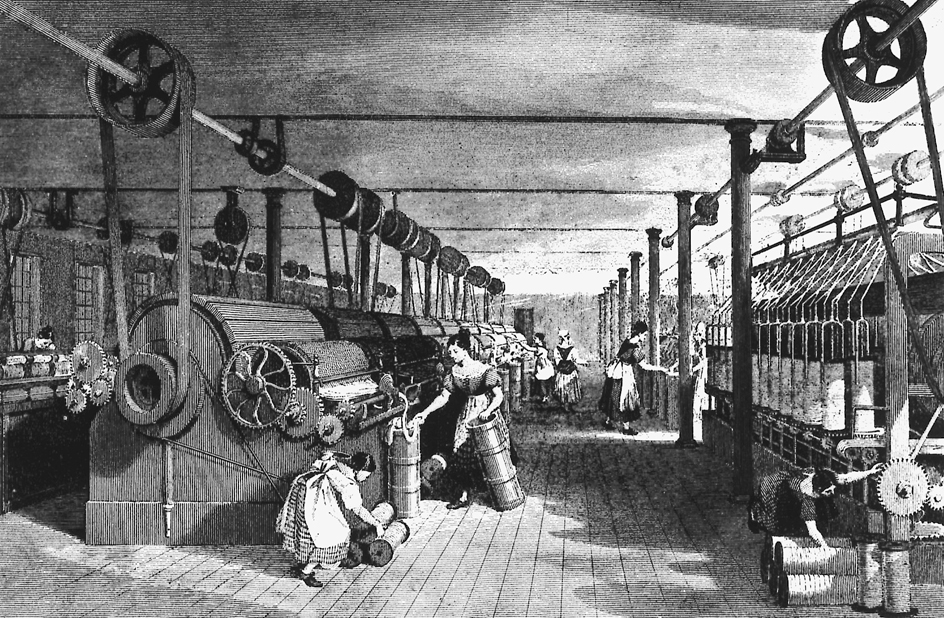

One of the most spectacular features of the Industrial Revolution was the introduction of power-driven machinery in the textile industries of England and Scotland. This introduction took place between 1780 and 1810 and marked the beginning of the age of the modern factory.

Before the industrialization of the textile industry, merchants purchased raw materials and distributed them among workers who lived in cottages on farms or in villages. Some of these workers spun the plant and animal fibers into yarn, and others wove the yarn into cloth. This system was called domestic or cottage industry.

Under the domestic system, merchants bought as much material and employed as many workers as they needed. The merchants financed the entire operation. Some of them owned the spinning and weaving equipment and the workers’ cottages. However, the workers had much independence and set their own pace of work. They often accepted work from several merchants at the same time.

The domestic system presented many problems for the merchants. They had difficulty regulating standards of workmanship and maintaining schedules for completing work. Workers sometimes sold some of the yarn or cloth for their own profit. As the demand for cloth increased, merchants often had to compete with one another for the limited number of workers available in a manufacturing district. All these problems raised the merchants’ costs. As a result, the merchants turned increasingly to machinery for greater production and to factories for central control over their workers.

Spinning machines.

For hundreds of years before the Industrial Revolution, spinning had been done in the home on a simple device called a spinning wheel. One person operated the wheel, powering it with a foot pedal. The wheel produced only one thread at a time.

The first spinning machines were crude devices that often broke the fragile threads. In 1738, Lewis Paul, an inventor from Middlesex (now part of London), and John Wyatt, a Lichfield mechanic, patented an improved roller-spinning machine. This machine pulled the strands of material through sets of wooden rollers that moved at different speeds, making some strands tighter than others. When combined, these strands were stronger than strands of uniform tightness. The combined strands passed onto the flier, the part of the machine that twisted the strands into yarn. The finished yarn was wound onto a bobbin that revolved on a spindle. Mechanically, the roller-spinning machine was not completely successful. However, it was the first step in the industrialization of textile manufacturing.

In the 1760’s, two new machines revolutionized the textile industry. One was the spinning jenny, invented by James Hargreaves, a Blackburn weaver and carpenter. The other machine was the water frame, or throstle, invented by Sir Richard Arkwright, a former Preston barber. Both machines solved many of the problems of roller spinning, especially in the production of yarn used to make coarse cloth.

Between 1774 and 1779, a Lancashire weaver named Samuel Crompton developed the spinning mule. This machine combined features of the spinning jenny and the water frame and, in time, replaced both machines. The mule was particularly efficient in spinning fine yarn for high-quality cloth, which, before the invention of the mule, had been imported from India. During the 1780’s and 1790’s, larger spinning mules were built. They had metal rollers and several hundred spindles. These machines ended the home spinning industry. For further information on the development of spinning machines, see Spinning.

The first textile mills appeared in Britain in the 1740’s. By the 1780’s, England had 120 mills, and several had been built in Scotland.

Weaving machines.

Until the early 1800’s, almost all weaving was done on handlooms because no one could solve the problems of mechanical weaving. In 1733, John Kay, an English engineer, invented the fly shuttle (also called flying shuttle). This machine made all the movements for weaving, but it often went out of control.

In the mid-1780’s, an Anglican clergyman named Edmund Cartwright developed a steam-powered loom. In 1803, John Horrocks, a Lancashire machine manufacturer, built an all-metal loom. Other British machine makers further improved the steam-powered loom during the early 1800’s. By 1835, the United Kingdom had more than 120,000 power looms. Most of them were used to weave cotton. After the mid-1800’s, handlooms were used only to make fancy-patterned cloth, which still could not be made on power looms. See Weaving.

The steam engine.

Many of the most important inventions of the Industrial Revolution required much more power than horses or water wheels could provide. Industry needed a new, cheap, and efficient source of power and found it in the steam engine.

The first commercial steam engine was produced in 1698. That year, Thomas Savery, a Cornish army officer, patented a pumping engine that used steam. In 1712, Thomas Newcomen, a Devonshire tool seller, created an improved engine. Newcomen’s engine came into general use during the 1720’s.

Newcomen’s steam engine had serious faults. It wasted much heat and used a large amount of fuel. In the 1760’s, a Scottish engineer named James Watt began working to improve the steam engine. By 1785, he had eliminated many of the problems of earlier engines. Watt’s engine used heat much more efficiently than Newcomen’s engine and used less fuel. For more information on the development of the steam engine, see Steam engine (History).

The enormous potential of the steam engine and power-driven machinery could not have been achieved without the development of machine tools to shape metal. When Watt began working with the steam engine, he could not find a tool that drilled a perfectly round hole. As a result, his engines leaked steam. In 1775, John Wilkinson, a Staffordshire ironmaker, invented a boring machine that drilled a more precise hole. Between 1800 and 1825, English inventors developed a planer, which smoothed the surfaces of the steam engine’s metal parts. By 1830, nearly all the basic machine tools necessary for modern industry were in general use.

Coal and iron.

The Industrial Revolution could not have developed without coal and iron. Coal provided the power to drive the steam engines and was needed to make iron. Iron was used to improve machines and tools and to build bridges and ships. Britain’s large deposits of coal and iron ore helped make it the world’s first industrial nation.

Early ironmaking.

To make iron, the metal must be separated from the nonmetallic elements in the ore. This separation process is called smelting (see Smelting). For thousands of years before the Industrial Revolution, smelting had been done by placing iron ore in a furnace with a burning fuel that lacked enough oxygen to burn completely. Oxygen in the ore combined with the fuel, and the pure, melted metal flowed into small molds called pigs. The pigs were then hammered by hand into sheets. Beginning in the early 1600’s, the pigs were shipped to rolling mills. At a rolling mill, the pig iron was softened by reheating and rolled into sheets by heavy iron cylinders.

The most practical fuel for smelting was charcoal, made by burning hardwoods. Most of Britain’s iron ore deposits and hardwood forests were in rural areas. Smelting and rolling thus became rural activities done by local workers. Since the 1600’s, charcoal had been used in many other manufacturing processes besides smelting and rolling. Wood was also in demand for other purposes. As a result, Britain had almost used up its hardwood forests by the early 1700’s. Charcoal became so expensive that many ironmakers in Britain quit the industry because of the high costs of production.

The revolution in ironmaking.

In 1709, Abraham Darby, a Shropshire ironmaker, succeeded in using coke to smelt iron. Coke is made by heating coal in an airtight oven. Smelting with coke was much more economical and efficient than smelting with charcoal. But most ironmakers continued to use charcoal. Manufacturers complained that coke-smelted iron was brittle and could not be worked easily. They still preferred the more workable iron smelted with charcoal. About 1750, Darby’s son Abraham Darby II developed a process that made coke iron as easy to work as charcoal iron. After 1760, coke smelting spread throughout Britain.

In the 1720’s, an important breakthrough occurred in rolling the iron. Grooves were added to the rolling cylinders, allowing manufacturers to roll iron into different shapes, instead of simply into thin sheets.

A Fareham ironmaker named Henry Cort took out a patent for improved grooved rollers in 1783. The next year, he patented a puddling furnace. Cort did not invent the puddling furnace, but he made great improvements in it. The puddling process produced high-quality iron. Pig iron was reheated in Cort’s puddling furnace until it became a paste. A person called a puddler stirred the paste with iron rods until the impurities were burned away. The purified iron was then passed through Cort’s grooved rollers and formed into the desired shape.

Before Cort developed his puddling furnace, ironmakers had to use charcoal to reheat the pig iron for rolling. But Cort’s furnace—with its combined rolling mill—used coke. The use of coke for smelting and puddling finally freed the British iron industry of any dependence on charcoal. In addition, the smelting, puddling, and rolling steps could be combined into a continuous operation near the coal fields. As a result, the British iron industry became concentrated in four coal-mining regions—Staffordshire, Yorkshire, southern Wales, and along the River Clyde in Scotland.

Ironmaking techniques continued to improve, and iron production expanded enormously. In 1788, for example, British ironmakers produced about 76,000 tons (68,900 metric tons) of iron. In 1806, they produced more than three times that amount. During the mid-1700’s, probably only about 5 percent of all British iron was made into machine parts. Most machines were made of wood. But by the early 1800’s, manufacturers used iron to make numerous products, including machine frames, rails, steam engine parts, and water pipes.

Transportation.

The growth of the Industrial Revolution depended on industry’s ability to transport raw materials and finished goods over long distances. Thus, the story of the Industrial Revolution is also the story of a revolution in transportation.

Waterways.

Britain had many rivers and harbors that could be adapted to carrying freight. Until the early 1800’s, waterways provided the only cheap and effective means of hauling coal, iron, and other heavy freight.

British engineers widened and deepened many streams to make them navigable. They also built canals to link cities and to connect coal fields with rivers. In 1777, the Grand Trunk Canal connected the River Mersey with the Trent and Severn rivers and thus linked the English ports of Bristol, Hull, and Liverpool. British engineers also built many bridges and lighthouses and deepened harbors. Parliament had to approve many of these construction efforts because they often involved the take-over of private land.

In 1807, the American inventor Robert Fulton built the first commercially successful steamboat. Within a few years, steamboats became common on British rivers. By the mid-1800’s, steam-powered ships were beginning to carry raw materials and finished products across the Atlantic Ocean.

Roads.

Until the mid-1700’s, Britain had poor roads. Most usable roads extended only a short distance beyond a town. Horse-drawn wagons traveled with difficulty, and pack animals carried goods over long distances. People rarely traveled by stagecoach. They rode horseback or walked.

A series of turnpikes was built between 1751 and 1771. These roads made travel by horse-drawn wagons and stagecoaches easier. But by the late 1700’s, the turnpikes needed repairs badly.

Two Scottish engineers, John Loudon McAdam and Thomas Telford, made important advances in road construction during the early 1800’s. McAdam originated the macadam type of road surface, which consists of crushed rock packed into thin layers. Telford developed a technique of using large flat stones for road foundations. These new methods of roadbuilding made travel by land faster and smoother. As a result, manufactured goods could be delivered more efficiently. The orders and money involved in business and industry also moved faster and more simply.

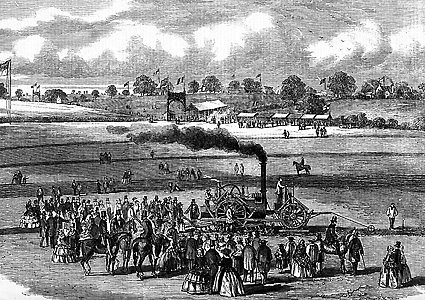

Railroads.

The first rail systems in Britain carried coal. Horses pulled the freight cars, which moved on iron rails. In 1804, a Cornish engineer, Richard Trevithick, built the first steam locomotive. Several other locomotives were built during the next 20 years, and they were used to haul freight at coal mines and at ironworks. However, industry generally preferred to use stationary engines that pulled the freight cars by means of cables. Steam locomotives did not begin to come into general use for passenger and freight transportation until the late 1830’s. See Railroad (History); Locomotive (History).

The role of capital.

Individual investors played a vital part in the growth of the Industrial Revolution from the beginning. During the 1700’s, many British merchants made fortunes from European wars, from the slave trade with North America, or from commerce with British colonies. Consumer activity also increased within Britain at the same time. Merchants as well as others in Britain began seeking investment opportunities.

Gradually, banks were founded to handle the increased flow of money. In 1750, London had 20 banks. By 1800, the city had 70.

Most banks did not directly invest in factories or make loans to factory owners for the purchase of machinery. Some banks, however, made short-term loans to industrialists to cover their operating expenses. Such loans allowed industrialists to use their own money to buy equipment and improve and expand their factories.

As machinery and factories became more expensive, the individuals who provided capital grew increasingly important. These industrial capitalists soon became one of the most powerful forces in British commercial and political life. Most capital came from merchants who lent it to people familiar with industrial tools, machines, and processes. In many cases, these people were friends or relatives of the merchants.

Life during the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution caused great changes in people’s way of life. The first changes appeared locally. But by the early 1800’s, most British people knew they were in the midst of a nationwide economic and social revolution. Educational and political privileges, which once had belonged largely to the upper class, spread to the growing middle class. Some workers were displaced by machines, but others found new jobs working with machinery. Both workers and employers had to adjust to a new cold and impersonal relationship. In addition, most workers lived and worked under harsh conditions in the expanding industrial cities.

The working class.

Under the domestic system, many employers had a close relationship with their workers and felt some responsibility for them. But such relationships became impossible in the large factories of the Industrial Revolution. Industrialists employed many workers and could not deal with them personally. The working day probably was no longer under industrialism than under the domestic system—about 12 to 14 hours a day for six days a week. But in the factories, the machines forced workers to work faster and without rest. Jobs became more specialized, and the work became monotonous.

Factory wages were low. Some employers kept them low deliberately. Many people agreed with the English writer Arthur Young, who wrote: “Everyone but an idiot knows that the lower classes must be kept poor, or they will never be industrious.” Women and children worked as unskilled laborers and made only a small fraction of men’s low wages. Children—many of them less than 10 years old—worked from 10 to 14 hours a day. Some were deformed by their work or disabled by unsafe machines. See Child labor.

Most factory workers, like other types of workers, were desperately poor and could not read or write. Housing in the growing industrial cities could not keep up with the migration of workers from rural areas. Severe overcrowding resulted, and many people lived in extremely unsanitary conditions that led to outbreaks of disease. During the 1830’s, for example, the life expectancy for men in Birmingham, England, was only slightly more than 40 years. See City (Industrial cities).

Until the early 1800’s, British employers usually held the advantage in relations with their employees. Workers were not permitted to vote and could do little legally to improve their condition. British law forbade trade unions, and workers who joined a union could be imprisoned.

However, some workers did form trade unions. Many workers also went on strike or rioted. In the riots, unemployed workers destroyed machinery in an attempt to gain revenge against the employers they blamed for depriving them of jobs. Even employed workers took part in the riots and wrecked the machines as a protest against their low wages and terrible working conditions. In 1769, Parliament passed a law making the destruction of some kinds of machinery punishable by death. But workers continued to riot against machines. In 1811, organized bands of employed and unemployed workers called Luddites began attacking factories and wrecking textile machines. The Luddites received their name from their mythical leader, Ned Ludd. Their movement lasted until 1816.

The working and living conditions of the working class improved gradually during the late 1800’s. Parliament, which had largely represented only the upper class, began to act in the interests of the middle and working classes. It repealed the law forbidding trade unions and passed other laws regulating factory conditions. In 1832, a Reform Act gave most middle-class men the right to vote. Another Reform Act, passed in 1867, granted the right to vote to many city workers and owners of small farms.

The middle and upper classes.

Although the workers did not at first share in the prosperity of the Industrial Revolution, members of the middle and upper classes prospered from the beginning. Many people made fortunes during the period. The revolution made available products that provided new comforts and conveniences to those who could afford them. The middle class, which consisted of business and professional people, won political and educational benefits. As the middle class gained in power, it became increasingly important politically. By the mid-1800’s, big business interests largely controlled British government policies.

Before the Industrial Revolution, England had only two universities, Oxford and Cambridge. But the revolution created a need for engineers and for clerical and professional workers. As a result, education became vital. Some libraries, schools, and universities were founded by private persons or groups, especially non-Anglican Protestants.

The Industrial Revolution indirectly helped increase Britain’s population. As people of the middle and upper classes enjoyed better diets and lived in more sanitary housing, they suffered less from disease and lived longer. The material condition of the working class also improved. Partly as a result of these improved conditions, the population grew rapidly. In 1750, Britain had about 61/2 million people. By 1830, the population had increased to about 14 million.

Spread of the Industrial Revolution

The techniques of industrialization began to spread from Britain to other countries soon after the Industrial Revolution started. Britain tried to maintain a monopoly of its discoveries and skills. British law prohibited the emigration of craftworkers until 1824 and prohibited the export of machinery until 1843. Nevertheless, hundreds of skilled workers and manufacturers left Britain, taking knowledge of industrialization with them.

In 1750, John Holker, a Lancashire manufacturer, settled in France, where he helped modernize spinning techniques in the textile industry. Samuel Slater, a Derbyshire textile worker, immigrated to the United States in 1789 and later established a spinning mill in Rhode Island. William Cockerill, a Lancashire carpenter, moved to Belgium in 1799 and began to manufacture textile machinery. In 1817, Cockerill’s son John established factories near Liege that produced bridge materials, cannon, locomotives, and steam engines.

Some manufacturers in the United Kingdom permitted people from other countries to inspect their factories. From 1810 to 1812, Francis Cabot Lowell, an American businessman, visited Lancashire textile mills. Lowell returned to the United States and established a textile factory in Waltham, Massachusetts. This factory was one of the first in the world to combine under one roof all the processes for manufacturing cotton cloth. In 1838, the famous German industrialist Alfred Krupp went to Sheffield, where he learned the most up-to-date processes for making steel.

The export of British capital became even more important than the export of people and machines in the spread of the Industrial Revolution. For hundreds of years, British merchants had extended credit and made loans to customers in other countries. As the Industrial Revolution grew, the flow of British capital to other countries increased. The flow became a flood with the coming of the railroad. British companies financed the export of locomotives, iron for rails, and experts to build and operate railroads in many countries.

Belgium

became the second country to industrialize. Steam engines were first installed there in the early 1700’s. Between 1830 and 1870, the nation rapidly developed its heavy industry with much financial support from the government. Textile making, which had been important in Belgium for many years, was industrialized. The cities of Ghent, Liege, and Verviers developed into major textile-manufacturing centers. Belgian coal fueled the textile factories.

France

made little industrial progress before the 1790’s. Industrialization was further slowed by the French Revolution (1789-1799) and by the wars of Napoleon Bonaparte, who ruled France during the early 1800’s. After Napoleon left the throne permanently in 1815, the French government encouraged industrial development. But by 1850, more than half of France’s iron production still came from old-fashioned and expensive charcoal furnaces. After 1850, however, coke rapidly replaced charcoal for smelting and puddling.

A poor transportation system weakened French industry during most of the 1800’s. The transportation system had fallen into bad condition during the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. Although the government deepened and widened many rivers and canals, these improvements did not meet the needs of growing industries in France. In 1842, the government also approved the building of a national railway system, but many complications forced long delays in its construction. France remained largely a country of farms and small businesses. After World War II (1939-1945), the French government began a series of national plans to modernize the economy.

Germany

had the natural resources needed for industrialization, but political and social obstacles held the country back. Until Germany was unified in 1871, it was a collection of separate states that often failed to cooperate with one another in economic matters. In addition, a small group of landowners controlled much of the land. In the early 1800’s, the government of the state of Prussia gradually took steps to provide for the industrial development of the land and its minerals. At the same time, Prussia succeeded in arranging agreements among the German states on common tariffs.

Between 1830 and 1850, the coal production in Germany doubled. About 1850, iron ore mining in Germany began to increase sharply. As a result, the number of furnaces fueled by coke also increased rapidly. Foreign investors and new German investment banks provided money for the booming iron industry. Germany’s steel production also began to grow rapidly in the late 1800’s. By 1900, its steel production exceeded that of the United Kingdom and ranked second to that of the United States.

The United States.

The first industrialization outside Europe occurred in the British colonies that became the United States. The colonies had a wide range of industries. The most successful was shipbuilding. By the time the colonies declared their independence in 1776, about a third of Britain’s ships were being built in America. Iron manufacturing was also a major industry, and a few American companies exported iron to Britain.

By the early 1800’s, the small arms industry in the United States had developed machines and machine tools that could produce standard parts that were required for mass production (see Mass production). Industrial production, especially of textiles and light metals, began to increase sharply in the United States in the 1820’s. The greatest increases in manufacturing took place in New England. Industrialization also benefited from improvements made in rivers and canals. These improvements reduced the cost of transporting goods to and from the interior of the country.

Beginning in the 1830’s, industrialization increased rapidly throughout the eastern United States. The iron industry in Pennsylvania made especially great advances as iron was adapted for agricultural tools, railroad track, and a variety of structural uses. By the 1850’s, the quality and price of American iron enabled U.S. ironmakers to compete with British ironmakers in the international market.

During the mid-1800’s, the agricultural, construction, and mining industries expanded as the population spread westward. Manufacturing accounted for less than a fifth of all U.S. production in 1840. By 1860, it accounted for a third. Agricultural products still made up more than two-thirds of the value of all U.S. exports in 1860, and the country still imported more manufactured goods than it exported. But by the late 1800’s, the United States had become the largest and most competitive industrial nation in the world.

By 1870, the main trends of the Industrial Revolution were clearly marked in all industrialized countries. Industry had advanced faster than agriculture. Goods were being made by power-driven machinery and assembled in factories, where management planned operations and the workers did little more than tend the machines. Capital controlled industrial production, but labor was being allowed to organize to fight for higher wages, shorter hours, and better working conditions. The railroad, the improved sailing ship, the steamship, and the telegraph had reduced the cost and time of transportation and communication. Living standards of the workers in industrial countries were higher than they had ever been. Populations grew rapidly, and more people lived in cities than ever before.