International law is the body of customs, treaties, and general principles that sovereign states, corporations, and individuals are expected to observe in their relations with one another. A sovereign state is one that is free from outside control. Some international laws result from years of custom. Others have been agreed to in treaties or determined by court decisions. Still others originate in general principles of law recognized by civilized nations. In an era of increased globalization, international law has become a subject of intense debate.

Many of the customs of international relations have existed for hundreds of years. For example, the ancient Greeks protected foreign ambassadors from mistreatment, even in wartime. For about 2,000 years, nations have given ambassadors similar protection.

Treaties between countries have been in use for thousands of years. Such treaties as the one that established the Pan American Union may be signed by many nations. Or they may be signed by only two or three nations, as in the case of trade treaties the United States has signed with other countries. According to the Statute of the International Court of Justice, in settling international disputes, the International Court of Justice should apply not only treaties and customs but also general principles of law recognized by civilized nations.

Kinds of international law

International law is generally divided into two types: public international law and private international law. Public international law is concerned with relations between nations. Private international law involves relations between individuals, companies, or nongovernmental organizations of different countries.

Public international law

is further divided into the laws of peace, the laws of war, and the laws of neutrality.

The laws of peace

define the rights and duties of nations at peace with one another. Each country has a right to existence, legal equality, jurisdiction over its territory, ownership of property, and diplomatic relations with other countries. Many of the laws of peace deal with recognizing countries as members of the family of nations and recognizing new governments in old nations. Most governments are recognized de jure—that is, as rightful governments. Under unsettled conditions, a government may be recognized de facto—that is, as actually controlling the country, whether or not by right. Rules dealing with territory include the rights and duties of aliens (noncitizens), the right of passage through territorial waters, and the extradition of criminals.

The laws of war

are recognized under traditional international law. Warring states are called belligerents. The laws of war provide definite restrictions on methods of warfare. For example, undefended towns, called open cities, must not be bombarded. Private property must not be seized by invaders without compensation. Surrendering soldiers may not be killed or assaulted and must be treated as prisoners of war.

All the laws of war have been violated repeatedly. In wartime, nations fight for their existence, and it is not always possible to get them to follow rules. Each nation does its best to destroy its enemy, and it uses the most effective weapons it can find.

Even in war, however, many international rules are observed. During World War II (1939-1945), many of the belligerent nations followed the international rules for the treatment of prisoners of war. Millions of former prisoners of war are alive today because these rules were followed more often than they were broken.

The laws of neutrality

are the international laws that govern neutral nations. Under international law, belligerents are forbidden to move troops across neutral territory. Neutral waters and ports must not be used for naval operations. Belligerent warships entering neutral ports must leave within 24 hours or be interned (confined).

In the 1800’s and 1900’s, neutral nations claimed many rights for their ships on the high seas. But laws about neutrals, like laws about war, are often broken. Neutral countries have been invaded in many wars, and neutral rights on the high seas are often ignored.

Private international law,

also known as conflict of laws, helps to provide guidance and settle international disputes between persons and other nongovernmental parties. Private international law has become increasingly important as globalization intensifies and international economic and social activity increases. This branch of international law focuses primarily on questions of jurisdiction and choice of law—that is, where international disputes should be settled and whose laws should be used to settle them.

The need for private international law arose as soon as individuals from different countries began to interact. Today, many nations recognize a clear need for private international law governing contracts. The United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods, for example, is a private and uniform international sales law. Still, many issues of private international law remain unsettled and a source of intense international debate. Such issues include electronic commerce, child abduction, and inter-country adoption.

The Hague Conference on Private International Law attempts to harmonize private international law. This global, intergovernmental organization is located at The Hague in the Netherlands. Currently, more than 70 nations and the European Union are members.

Enforcement of international law

After a legislative body passes a law, the government enforces the laws, and people who break them are tried in courts. However, there is no international legislature to pass laws that all nations are required to observe. Neither is there an international enforcement body to make countries obey international law. As a result, it is often difficult to enforce international law.

Consent of nations.

International laws that are observed by more countries are more influential. Some rules are accepted by all nations as part of international law. These rules cover such items as the sanctity of treaties, the safety of foreign ambassadors, and each nation’s jurisdiction over the airspace above its territory. Other rules are accepted by the majority of countries, especially those that are most powerful. One law of this type is the rule that each nation has jurisdiction over its territorial waters, a water area typically claimed to extend 12 nautical miles (22 kilometers) from its shores. Many nations follow this rule, but some do not. Ecuador and Peru, for example, claim a limit of 200 nautical miles (370 kilometers). International law also includes agreements, such as trade treaties, between two nations or among a few nations.

Violations.

Japan violated international law in 1941 by attacking Pearl Harbor without first declaring war. Germany broke international law during World War II when the German government killed millions of European Jews and forced slave laborers from other European countries to work in German war factories. The Soviet Union violated international law by refusing to repatriate (send home) many prisoners of war long after the end of World War II.

The United Nations (UN) received reports about the cruel treatment of many UN prisoners of war by the Chinese Communists and North Koreans in the Korean War (1950-1953). Violations occurred in the Nigerian civil war (1967-1970), the Pakistani civil war (1971), and the Vietnam War (1957-1975). In 1990, during the crisis that resulted in the Persian Gulf War of 1991, Iraq broke international law by using foreign hostages as “human shields” to discourage attacks against military and industrial sites.

Violations of international law, however, do not invalidate the laws themselves. The laws of cities, states, and nations are often broken, but such laws remain an active force. No nation denies the existence of international law.

Courts and arbitration.

In the belief that arbitration (settlement by agreement) is a better method than war to settle disputes, the Permanent Court of Arbitration was established in 1899 at The Hague, the Netherlands. Members of the court serve as arbitrators, not as judges.

In 1920, the League of Nations set up the Permanent Court of International Justice. The United Nations took over the court in 1946 and renamed it the International Court of Justice. This court issues judgments on boundary disputes and other questions of international law. Nations are not required to use the court, but they must accept its decisions if they do use it. In 1998, 120 UN member nations approved a treaty calling for the establishment of an independent court, the International Criminal Court (ICC), for the prosecution of war crimes and other offenses. The ICC began operations in 2003. It has jurisdiction over crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes.

Punishment.

There is no uniform way to enforce international laws. Laws within countries provide penalties for those who break them. But in the society of nations, no individual nation has the power to punish other nations or to force them to submit their disagreements to courts of arbitration. If an aggressor refuses to arbitrate, an injured nation may resort to self-help, which may mean war. But when the aggressor is strong and the injured nation is weak, such action is not practical. Treaties for united action, such as the North Atlantic Treaty, provide help for weaker nations in such cases. The UN Charter provides for collective defense.

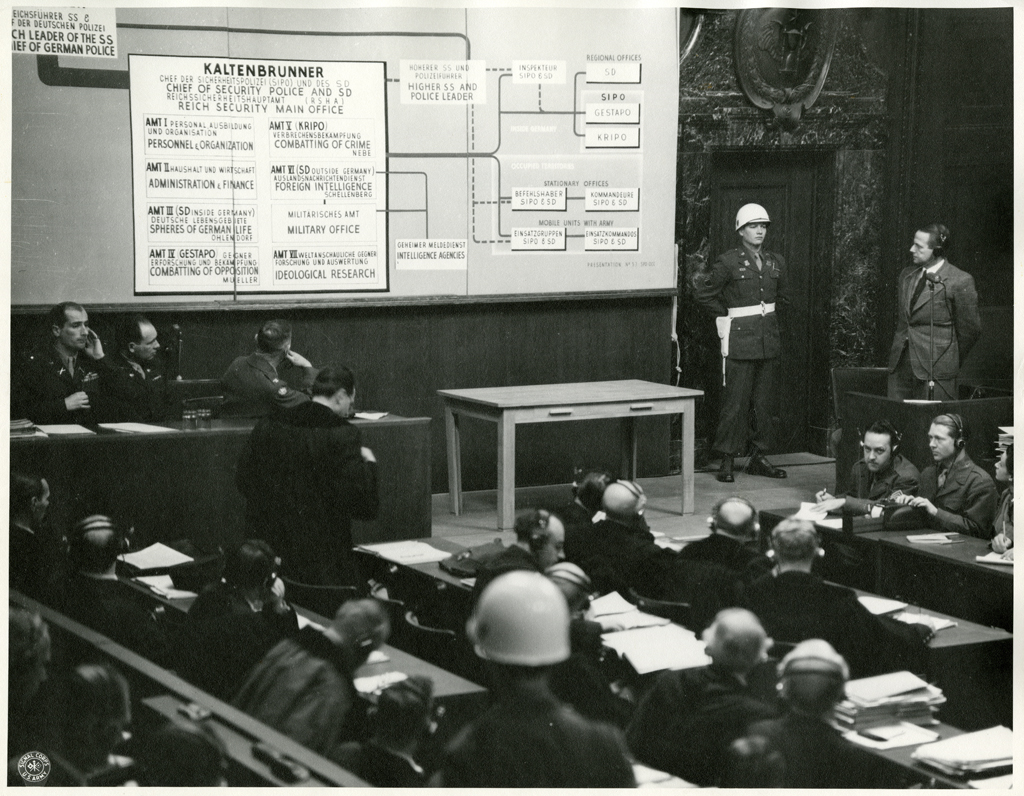

The trials of German and Japanese leaders at Nuremberg and Tokyo after World War II were an important step in the development of international law. Some of the leaders were charged, not only with breaking the laws of war, but also with bringing about the war itself. Enforcement of international laws by punishing persons who break them represents an important addition to the theory of international law. The International Law Commission of the United Nations has given much study to improved ways of formulating and enforcing international law.

History

Early history.

For thousands of years, international law consisted only of customs and treaties made by two or three nations. In the 1600’s, Hugo Grotius, a Dutch statesman, expressed the idea that all nations should follow certain international rules of conduct. For this idea and his writings on the subject, Grotius is often called the father of international law.

In the 1800’s,

international conferences were held to try to set up rules nations would obey in time of war. The first important conference met at Geneva in 1864. It made rules for the humane treatment of the wounded and the safeguarding of the noncombat personnel who cared for them. The Geneva Convention showed that rules could be written for nations to follow.

As a result of international conferences held at The Hague in 1899 and 1907, the laws of war, of peace, and of neutrality were collected and embodied in 14 conventions. They covered such subjects as the rights and duties of neutrals in case of war on land and in naval war, and the peaceful settlement of international disputes. Only 12 nations signed the first Geneva Convention. But 44 nations met at the Hague Peace Conference of 1907, and most signed many of the conventions.

After World War I,

many persons hoped that the League of Nations, established in 1920, would be able to enforce international law and prevent a second world war. Under the Covenant of the League of Nations, members were not allowed to go to war until three months after an arbitration court or the Council of the League had tried to end a dispute. But after the Japanese invaded Manchuria in 1931, the League could only condemn the invasion as a breach of international law. Japan then withdrew from the League and continued to attack China. Italy followed Japan’s example in 1935, when Italian troops invaded Ethiopia.

Between 1928 and 1934, more than 60 nations signed the Kellogg-Briand Pact, under which they agreed not to use war to gain their aims. But the pact did nothing about the causes of war. Its failure led many people to believe that nothing could stop wars and that international law should only try to make war less brutal.

After World War II,

the United Nations was formed as an organization to preserve the peace. Many people hoped the UN General Assembly might in time become a world legislature that could pass international laws. They believed the UN could profit from the mistakes of the League of Nations and succeed where the League had failed. Most of the nations that signed the UN Charter at San Francisco in 1945 believed the UN should be given the power to enforce its decisions—by force of arms if necessary. The United Nations Security Council was given the authority to determine whether nations were endangering world peace by their actions.

In 1949, UN arbitration succeeded in stopping a war in Israel. In 1950, the UN became the first world organization to use force to stop aggression. Communist forces from North Korea invaded the Republic of Korea in June 1950, and the UN Security Council agreed on a “police action.” Sixteen UN countries sent armed forces to aid South Korea, with the United States and South Korea providing most of the troops and supplies. After the UN forces drove the Communists back into North Korea, a truce was signed in July 1953.

The UN has continued its efforts to resolve conflicts in such disturbed regions as the Near East and Southeast Asia. But many nations have tended to favor direct negotiations with one another instead of discussion through the UN. In 1969, for example, the United States and the Soviet Union began the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks. In 1972, those talks led to major agreements that limited each nation’s defensive and offensive nuclear missiles.

Efforts by the UN and direct negotiations among nations have helped lessen the danger of war. But governments have failed to create a system of international law that prevents nations from using force to achieve their aims. Many countries have used such force. For example, the Soviet Union sent troops into Hungary in 1956 and into Czechoslovakia in 1968 to ensure that both nations would remain Communist. During the Vietnam War (1957-1975), the United States fought in an unsuccessful attempt to prevent the Communist take-over of South Vietnam. In the Persian Gulf War of 1991, a U.S.-led coalition of nations drove Iraqi troops from Kuwait after Iraq had invaded that country in 1990. The coalition’s actions were based on a number of UN Security Council resolutions.

In late 2002 and early 2003, members of the UN Security Council debated whether a second war against Iraq was necessary to confront Iraq’s suspected possession of illegal weapons. The United States pressed for military action, while such countries as France, Germany, and Russia argued for more time to pursue a diplomatic solution. The sides were unable to reach an agreement. In March 2003, a U.S.-led coalition began a military invasion that led to the fall of the Iraqi government of Saddam Hussein. Because the invasion did not have the backing of the UN Security Council, some people argued that it violated international law.