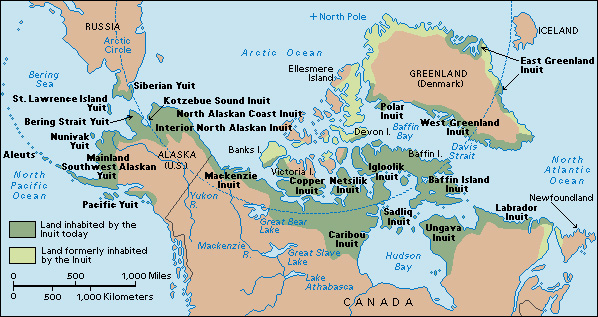

Inuit << IHN yoo iht >> are people who live in and near the Arctic. Their homeland stretches from the northeastern tip of Russia, eastward across Alaska and northern Canada, to Greenland. Many Inuit live farther north than any other people in the world.

The name Inuit means the people or real people. It comes from a language called Inuit-Inupiaq. The singular of Inuit is Inuk, which means person. Dialects of the Inuit-Inupiaq language are spoken by Inuit in Canada, Greenland, and northern Alaska.

The Iñupiat are Inuit who live in northern Alaska. The singular of Iñupiat is Inupiaq, which means real person. The Inupiaq language is part of the Inuit-Inupiaq language family. As in other Inuit cultures, hunting is central to the traditional Iñupiat way of life.

Another group of Arctic people, the Yuit, are often called Inuit as well. Their culture resembles that of other Inuit, but they speak a different language called Yupik. The Yuit live in western and southern Alaska and in Siberia in Russia.

Inuit culture developed more than 1,000 years ago in what is now the Bering Sea region of Alaska and Siberia. Most Inuit have always lived near the sea, which has provided much of their food. The first Inuit hunted bowhead whales and other mammals.

As Inuit spread eastward, they modified their way of life to suit the Arctic environments they encountered. They caught fish and hunted seals, walruses, and whales. On land, they hunted a type of deer called caribou, musk oxen, polar bears, and many smaller animals. Inuit used the skins of these animals to make clothes and tents. They crafted tools and weapons from the animals’ bones, antlers, horns, and teeth. In summer, they traveled in boats covered with animal skin. In winter, they used sleds pulled by dog teams. Most Inuit lived in tents in the summer and in large sod houses during winter. When traveling in search of game in winter, they built snowhouses as temporary shelters.

The Inuit way of life began to change in the 1800’s. At that time, European whalers and traders began arriving in the Arctic in large numbers. Inuit eventually adopted many aspects of European culture and permanently altered their traditional way of life.

Today, there are about 150,000 Inuit in Russia, Alaska, Canada, and Greenland. Most live in towns or small settlements scattered along the Arctic coast. Inuit retain a considerable knowledge of their ancient culture. Many Inuit still spend much of their time in traditional activities, such as hunting and fishing.

Where Inuit live

Inuit live in one of the coldest and harshest regions of the world. Most kinds of plants and animals cannot live as far north as Inuit do.

Inuit lands include the northeastern tip of Siberia, the islands of the Bering Sea, and the coastal regions of mainland Alaska. They also include the north coast and islands of the Canadian Arctic and most of the west coast and part of the east coast of Greenland. The region is often called the Land of the Midnight Sun because the sun shines all day and all night for part of each summer. During part of each winter, however, some areas are continuously dark. See Midnight sun.

Climate.

Most of the Far North has long, cold winters and short, cool summers. Average temperatures in the region rise above freezing for only two or three months each year. During the coldest months, temperatures average between -20 and -30 °F (-29 and -34 °C). Annual snowfall averages between 15 and 90 inches (38 and 229 centimeters). Little of the snow melts until spring, and winter storms of wind-driven snow can force people to remain inside for days at a time. However, because snow contains much less water than rain, average precipitation (rain, melted snow, and other forms of moisture) totals only about 6 to 10 inches (15 to 25 centimeters) per year. Such scarce precipitation makes the Arctic technically a desert.

Thick sheets of ice cover parts of some northern Canadian islands and most of Greenland throughout the year. Rivers, lakes, and the sea itself remain frozen for much of the year. Even in summer, large pieces of ice float in the sea. When the wind blows toward the shore, it often piles this ice on beaches.

Plants and animals.

The land area of the Arctic consists mainly of huge treeless plains called tundra. In most places, only the top 1 to 10 feet (30 to 300 centimeters) of ground thaws in summer. Below that level, the ground remains permanently frozen in a condition called permafrost. During the summer, melted ice or snow creates many ponds, small lakes, and swamps.

The Arctic has no forests. Tundra vegetation consists of low shrubs, mosses, grasslike plants called sedges, and tiny flowering plants. Rootless, plantlike organisms known as lichens grow on many rocks. For a short time each summer, colorful flowers bloom in great abundance in the tundra.

Seals, walruses, whales, and polar bears live in the sea, on the sea ice, and along the Arctic shores. The tundra supports populations of caribou, musk oxen, wolves, foxes, and hares. Many of these animals migrate south annually and are available to Inuit hunters for only a few months each year. Numerous ducks and geese summer in the Arctic, where they build their nests and raise their young. Some birds, such as the ptarmigan << TAHR muh guhn >>, are year-round residents. Fish include Arctic char, Arctic cod, lake trout, salmon, and whitefish.

Traditional way of life

From the earliest beginnings of their culture, Inuit lived a way of life different from that of most other people. Inuit had little contact with other cultures for most of their history. Some occasionally met with other northern peoples that lived south of Inuit country. Such meetings were often hostile. Over time, however, strong trade relationships developed between these peoples.

Inuit have always lived in small groups scattered over a huge region. Many differences developed among the cultures of the widespread Inuit groups. These differences make it impossible to describe a general way of life for all Inuit. The following sections chiefly discuss the traditional way of life of Inuit in what is now Canada before the arrival of Europeans. Inuit no longer follow many of these customs.

Group life.

Inuit lived in groups that varied in size from a single family to several hundred people. The size of the groups depended on the amount of food available in different seasons. During the spring and fall in Alaska, the largest groups gathered where they could hunt migrating caribou. On the coast of Labrador, Inuit groups often formed large winter villages to share the food and other necessities provided by the killing of a bowhead whale. Many of these larger communities split up during the rest of the year. Small Inuit groups moved about the countryside in search of fish, seals, birds, and other game. These local groups were the most important social units for Inuit.

In most regions, an Inuit household consisted of a married couple, their unmarried children, and the married sons or daughters and their families. Some households also included one or more parents or unmarried siblings of the couple. Inuit groups governed themselves by traditional rules of conduct rather than written laws. The most important rule was that each individual help in the day-to-day activities that ensured the group’s survival.

When disputes arose, Inuit societies often settled them by contests of strength or some other peaceful means. Conflicts sometimes resulted in groups splitting off from one another. If an individual’s conduct threatened the safety or harmony of a group, that person was banished. Banishment usually meant death, because an individual could not survive alone in the Arctic.

Food.

The Inuit diet varied according to location and the seasons of the year. On the Alaskan coast and the coast of Labrador, the kill of a single bowhead whale provided tons of meat for an Inuit community. In other parts of Alaska, the fall caribou hunt supplied communities for the entire winter. Many Inuit obtained food from smaller animals, including hares and foxes.

Inuit also caught fish in the sea, lakes, and rivers. They ate berries and other plant foods when they were available. Delicacies included such items as the skin of beluga whales and fat from the backs of caribou.

Inuit often ate meat raw or frozen. When they cooked meat, they used pots made from a soft stone called soapstone. Soapstone lamps, which were fueled by blubber or oil from seals and whales, provided heat. Inuit cooks used a curved knife called the ulu << OO loo >> to prepare much of their food. The ulu was made in the form of a half moon. It had a blade of slate or metal and a handle of bone, ivory, or wood. Inuit ate from wooden plates and bowls, using forks made of bone. They drank from cups made of the horns of musk oxen.

Clothing.

Inuit made their clothing from the skins of animals. Styles varied from region to region, but in all regions men, women, and children wore the same general outfit. It consisted of a hooded jacket called a parka, trousers or leggings, socks, boots, and mittens. Inuit often wore goggles of wood, bone, or ivory to reduce glare from the sun. The goggles had small holes or narrow slits through which to see.

Inuit preferred caribou skin as a material for clothing. The skin was lightweight, and the inner hairs of the skin made it warm. Skins from seals, foxes, polar bears, and other animals served as substitutes for caribou. Inuit often decorated their clothing with furs, beads, and good luck charms such as carvings or parts of animals.

The parka fit loosely over the head, neck, and shoulders. It hung in varying lengths from above the waist to below the knees. Women often carried young children in the backs or hoods of their parkas. Most Inuit wore two layers of clothing in winter: an inner suit with the fur next to the skin and an outer suit with the fur on the outside. The air between the two layers provided insulation, and the fur allowed perspiration to evaporate. In warmer weather, Inuit wore only the inner suit of caribou or a suit of sealskin. Inuit used sealskin to make their tightly sewn boots.

Shelter.

Most Inuit families had both a summer and a winter dwelling. During the summer months, almost all Inuit lived in tents framed with wood and covered with seal or caribou skins. Some tents had raised platforms at the rear where people slept.

To build a winter house, Inuit first dug a large hole in the ground. The builders then piled rocks and sod around the outer boundary of the hole to form walls. Rafters of wood or whalebone topped the walls and were covered with sod. Often, Inuit excavated a sod-covered entrance passage below the level of the house floor. This passage kept warm air inside the house and cold air outside. Cold air became warmer as it flowed through the passage, and it then rose into the house. Inuit usually stored food in this entrance passage or in storage areas off of the passage. Inside the house, Inuit built sleeping platforms that filled most of the rear section. They also constructed platforms to hold oil lamps that provided heat and light. In addition, Inuit in some regions built a kitchen area near the entrance passage.

People often imagine that Inuit lived in snowhouses, called igloos, for much of the year. In fact, only Inuit in central Canada and the northern Canadian Arctic islands lived in snowhouses all winter. Most Inuit built snowhouses only as temporary shelters when traveling.

Inuit builders could construct a snowhouse in about two hours. First, they cut blocks of hard snow using a snow knife, a long, straight knife made from whalebone. They then stacked the blocks in a continuous, circular row that wound upward in smaller and smaller circles to form a dome-shaped house.

Inuit who used snowhouses as permanent winter dwellings built much more elaborate structures. They attached storage rooms to the snowhouse and excavated entrance passages similar to those in sod houses. Sometimes, a series of passages connected a group of snowhouses occupied by several families. Inuit arranged the interiors of permanent winter snowhouses in much the same fashion as sod houses. These interiors included both sleeping platforms and lamp platforms.

Transportation.

During winter months, most Inuit traveled on sleds. In summer, they walked over land and traveled by boat over water.

Inuit made two basic types of sleds: plank sleds and frame sleds. The plank sled was mostly used in Canada and Greenland and looked like a long ladder. It consisted of two long runners with a series of crosspieces lashed between them. Inuit preferred wood as the material to make plank sleds. In areas where wood was not available, Inuit used whalebone and even frozen animal skins. Frame sleds, used often in Alaska and Siberia, had a basketlike frame built on the runners. The frame slanted upward from the front to the back of the sled. For both kinds of sleds, Inuit fastened sled shoes of whalebone to the bottoms of the runners. These shoes were both durable and slippery.

Both types of sleds were pulled by dogs. Inuit in Canada and Greenland usually hitched each dog to the sled by a separate line. In this kind of hitch, the dogs fanned out in front of the sled as they pulled it. Inuit in Alaska and Siberia hitched their dogs in pairs along a central line.

Inuit kept as many dogs as they could feed. Inuit in northern Canada, who lived in a particularly harsh climate, usually had only 1 or 2 dogs. However, teams of 10 or more dogs were common in eastern Canada. During the summer, many Inuit used dogs to carry packs as they moved from place to place.

Inuit used two types of boats: the kayak << KY ak >> and the umiak << OO mee ak >>. The kayak resembled a canoe with a deck. It had a narrow body pointed at both ends. The body consisted of a carefully fitted wood or bone frame covered with the skin of caribou, seals, or walruses. Because Inuit normally used kayaks for hunting, they fitted harpoon rests to the deck. Most kayaks carried only one person, who sat in a hole in the deck. Some carried two people and had two holes. The design of the kayak remains popular today. Modern boatbuilders commonly make boats of synthetic materials that copy the kayak’s design.

To propel a kayak, Inuit used either a long paddle with a blade at each end or a short paddle with a single blade. A kayaker often wore a special waterproof jacket made from seal intestine. The boater fitted the edge of the jacket around the edge of the kayak opening and tied the jacket in front to form a waterproof seal. A person could tip over in a kayak, roll back up, and continue to float.

The umiak was a large open boat that usually carried 8 to 10 people. Umiaks consisted of a wooden frame covered with sealskin or walrus skin. Inuit propelled these boats with single-bladed paddles. Umiaks were used for long-distance travel. Inuit hauled their belongings in umiaks when they moved camp, and they used the boats for hunting walruses and whales.

Hunting and fishing

provided most of the food that Inuit ate and many of the raw materials for Inuit tools, weapons, clothing, and shelter. Inuit most commonly hunted seals and caribou, but they also killed whales, musk oxen, polar bears, hares, and birds.

Inuit hunted seals by different methods in different seasons. In winter, they hunted at the breathing holes that the seals kept open in the ice. Hunters used long bone tools called probes to find the angle of the holes. They then waited by these holes and killed the seals when the animals surfaced to breathe. Some Inuit used tools that indicated when a seal was using a breathing hole. These tools often consisted of feathers or of a long, thin sliver of wood or bone called an idlak << IHD lak >>. A hunter would stick the indicator into the breathing hole. When a seal swam over to the hole, its breath would cause the indicator to vibrate. Inuit would then kill the seal.

Inuit killed seals with harpoons. They made harpoon heads from bone or ivory and tipped the heads with a stone or iron point. After the harpoon struck the animal, the harpoon head detached from its shaft. A sealskin line fastened to the head held the animal securely. When hunting through the ice, Inuit held a handle at the end of the harpoon line.

In the spring, Inuit hunted seals as the animals climbed out onto the ice. The hunters stalked seals slowly and carefully. Many hunters approached their prey by imitating the seals’ movements as the animals awoke every minute or so to watch for danger. Other hunters stalked while hiding behind a movable hunting screen. Inuit also hunted seals from the ice edge during spring and from kayaks during the open water months of summer. When hunting from the ice edge or from kayaks, Inuit attached an inflated sealskin float to the other end of the harpoon line. This technique slowed the seal down and prevented the loss of the harpoon.

Inuit hunters used special bone plugs to close wounds in dead seals. These plugs held in the seal’s blood, which was a common part of the Inuit diet. Hunters then pulled the seals home using large pins or handles of bone, wood, ivory, or antler.

Most Inuit hunted caribou by shooting them with arrows from small, stout bows. Hunters could also spear caribou from kayaks when the animals crossed lakes or rivers. Inuit sometimes built rows of stone piles, which directed the caribou toward water crossings or other spots where hunters could spear them.

Inuit hunters also killed a variety of other animals. For example, many Inuit hunted whales by shooting them with darts—long, spearlike weapons that were tipped with poison. After shooting a whale, Inuit would wait a few days for the animal to die and wash up on shore. Hunters trapped foxes in stone traps. These traps had small holes at the top through which the fox could not escape. A few Inuit caught polar bears in huge stone traps. Usually, a hunter’s dogs surrounded the bear and kept it at bay until the hunter could kill it with a lance. In some other areas, Inuit set snares to catch birds and hares. They also killed birds by throwing multipronged spears into the flocks.

Inuit usually fished with a three-pronged spear called a leister << LEES tuhr >>. For much of the year, they fished through holes in the ice. In summer, Inuit often fished in shallow streams. Sometimes, they placed lines of rocks in the streams to channel the fish toward them.

Religion.

Inuit believed that all people, animals, things, and forces of nature had spirits. The spirits of people and animals lived in another world after they died. Other spirits included those of the wind, the weather, the sun, and the moon. One of the most important spirits to many groups was a goddess who governed the sea. In some areas, she was called Sedna << SEHD nuh >>. She lived at the bottom of the ocean and controlled the seals, whales, and other sea mammals.

Inuit followed special rules to please the spirits. They believed that if they ignored the rules, the spirits might punish them by causing sickness or other misfortune. In many communities, the wife of a hunter might offer a drink of water to an animal that had been killed. She would do this to satisfy its spirit. In Alaska, Inuit saved the bladders of the seals they killed. They believed a seal’s spirit rested within its bladder. In a special ceremony each year, the community returned the bladders to the sea to ensure good hunting in the year to come.

The death of an Inuk required certain observances. In many regions, Inuit wrapped the body in skins and left it on the tundra, covered by an arrangement of stones. They often placed tools, weapons, and other items with the body for use in the otherworld.

Inuit communities usually had an individual who they believed had special powers to communicate with the spirit world. Such a person was called an angekok << ANG guh kok >> by Inuit and a shaman by Europeans. These individuals could be either men or women. They healed the sick and tried to influence aspects of life over which people had little control. For example, they attempted to communicate with spirits to bring good weather and to ensure a steady supply of game.

Recreation.

The long Arctic winter was the time for storytelling and for passing Inuit traditions and mythology from one generation to the next. During winter, darkness and storms often kept people indoors for long periods. Inuit performed traditional dances to the beat of a large skin drum. Other activities included song contests and tests of strength such as wrestling and tug-of-war.

One of the most popular Inuit games was the blanket toss. A dozen or more people held a round blanket made of walrus hides sewn together. When they all pulled the blanket tight, a person on the blanket was tossed into the air. The one being tossed tried to land on his or her feet and often did somersaults in the air. Another popular game was ajegaq << AJ uh gahk >>, in which a bone drilled with holes was tossed in the air and caught on a pin or spike. Inuit children played with toy bows and arrows, leather balls, and dolls made of wood, skins, or ivory.

Arts and crafts.

Inuit elaborately carved or decorated many of the objects they used every day. These objects included needle cases, snow goggles, combs, pins, and many other items made from antler, bone, or walrus ivory. Inuit often carved pins and buttons into the forms of animals, such as seals and fish. They decorated clothing with some of these carvings and with the dyed skins of seals and the furs of foxes, wolves, and other animals.

Language.

Inuit included speakers of two related language groups. Most Inuit communities spoke dialects of the Inuit-Inupiaq language. These communities stretched from northwest Alaska to Greenland and southward into Hudson Bay and the Labrador coast. The other language, Yupik, was spoken in far eastern Siberia and along portions of the Alaskan coast.

Inuit formed many of their words by adding one or more suffixes to a root word. Such words could have five or more syllables. For example, the Inuit word igdlo means house, while the word igdlorssualiorpoq means he who builds a large house. Inuit languages included numerous words that reflected their own way of life. For example, Inuit used many terms for the seal. Different names depended upon the kind of seal, whether the animal was young or old, whether it was on land or in the water, and other circumstances.

History

Inuit origins.

People have lived in the Arctic for thousands of years. The earliest Arctic peoples were not closely related to modern Inuit. They did not hunt large whales or use dogs to pull their sleds, and their tools and weapons were different from Inuit tools and weapons.

Inuit culture developed in what is now the Bering Sea region about 1,000 years ago. The people there, who were of Asian origin, developed the technology to hunt huge bowhead whales. This culture spread eastward and is called the Thule << THOO lee >> culture, after the place in northern Greenland where archaeologists first discovered it.

The Thule people, the ancestors of Inuit, had reached present-day northern Alaska by A.D. 1000. There, they hunted bowhead whales along the shore during the whales’ annual migrations. About A.D. 1000, Thule people began to spread eastward into what are now the Canadian Arctic and Greenland. They also moved southward into what are now Hudson Bay and the coast of Labrador. The Thule people displaced or absorbed earlier residents who lived in many of these regions. Archaeological evidence indicates that this expansion occurred rapidly. For example, scientists have found remarkably similar tools, weapons, and house types at Thule archaeological sites from the Bering Sea region in the west to Greenland in the east. Scientists think that warming climates may have been partly responsible for this rapid spread.

As the Thule people moved throughout this vast Arctic region, they modified their culture to suit the different environments they found. The Caribou Inuit on the west coast of Hudson Bay, for example, lived on caribou and fish. Inuit on the Labrador coast hunted large whales.

In time, Inuit in each region of the Arctic came to recognize themselves as distinct cultural groups with their own individual dialects. The members of these groups usually called themselves after the places where they lived. These names end with the suffix -miut, which means the people of. For example, Aivilingmiut means the people of the village Aivilik.

The arrival of Europeans.

The first Europeans to meet Inuit were Norse settlers in the northern part of what is now the island of Newfoundland in Canada. These settlers lived there for a short time in about A.D. 1000. Beginning in the 1500’s, European whalers, fishing crews, and explorers met many Inuit along the coast of Labrador. The English explorer Martin Frobisher visited an Inuit village in the Baffin Islands in the 1570’s. He and his party wrote descriptions of the village and made paintings and drawings of some Inuit. Russians and other Europeans first met Inuit in what is now Alaska in the 1700’s. In the later 1700’s, Moravian missionaries from what is now Germany traded with Inuit in Labrador and converted many of them to Christianity.

In the mid-1800’s, whalers began to hunt in the Arctic. Some Inuit worked for whalers and traded with them. Inuit received firearms, ammunition, wood, iron, and other European goods. Unfortunately, European diseases often accompanied the whalers and traders. These diseases, which included smallpox and measles, completely wiped out some Inuit populations.

The Inuit way of life changed as a result of contact with Europeans. For example, many Inuit began trapping animals only for their furs, which they traded to Europeans for rifles and other goods. Because of the trapping, many animals that Inuit hunted became scarce. This scarcity, in turn, made Inuit more dependent upon European goods and permanently altered their traditional way of life. Nevertheless, many Inuit continued to follow their traditional ways well into the 1800’s.

New ways of life

began for most Inuit in the early and middle 1900’s. During that time, the impact of European societies on Inuit increased greatly. The industrialized cultures of Europe were extremely different from traditional Inuit societies, and many Inuit had difficulty adopting European lifestyles. The Inuit way of life changed in different ways in Russia, Alaska, Canada, and Greenland.

In Russia, the Communist government of the Soviet Union took control of all Inuit communities during the 1920’s. Russia was part of the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1991, when the Soviet Union was dissolved. The Soviet Communists provided improved health care, housing, and education for Inuit. However, they also forcibly relocated many Inuit groups from their traditional lands to other areas. Inuit were grouped with other Siberian peoples into economic units called collectives. The purpose of the collectives was to produce goods for sale throughout the country. Since Inuit could no longer hunt sea mammals for food, they began to sell walrus tusks and such handicrafts as bone and soapstone carvings.

In Alaska, hunting with rifles and widespread trapping greatly reduced the quantity of game animals by the late 1800’s. As a result, many Inuit became unable to survive independently. The United States government brought reindeer from Siberia in an attempt to start a reindeer herding industry. However, the industry failed. Inuit in Alaska became United States citizens in 1924.

During World War II (1939-1945), many Inuit worked at U.S. military bases in Alaska. After the war, some Inuit found part-time work in commercial fishing, construction, or other businesses run by the rapidly growing white population. But most Inuit could not find jobs. The U.S. government established programs to improve living conditions of Inuit, but many of them still lived in poverty.

In Canada, the Inuit way of life changed little until the 1950’s. At that time, the fur trade declined and the number of caribou decreased sharply after the animals had been hunted with rifles for many years. These developments led more and more Inuit to move to communities that had developed around trading posts, government administrative offices, radar sites, and mission churches. Inuit could find construction jobs and other temporary work in these communities. But there was not enough work for all Inuit. As a result, many of them began to receive housing and other assistance from the Canadian government.

In Greenland, many Inuit began fishing commercially during the early 1900’s. This development resulted from a change in climate that warmed Greenland’s coastal waters. The warm water drove the seals north and attracted cod, salmon, and other fish from the south.

Greenland was a colony of Denmark from 1380 until 1953, when it became a Danish province. At that time, Inuit in Greenland became Danish citizens. During the early 1900’s and mid-1900’s, the Danish government established programs to aid Inuit in Greenland. These programs provided improved education, housing, and health care. In addition, the Danish government helped train Inuit for jobs in manufacturing, service industries, and other fields.

Inuit today.

Most Inuit no longer live a traditional way of life. They live in wooden homes rather than in snowhouses, sod houses, or tents. They wear modern clothing instead of animal skin garments. Most Inuit speak English, Russian, or Danish in addition to their native language. The kayak and umiak have given way to the motorboat, and the snowmobile has replaced the dog team. Christianity has taken the place of most traditional Inuit beliefs.

Inuit today must compete in the modern economic world, rather than the natural world. While some Inuit have adjusted to their new ways of life, many experience unemployment and other problems. In addition, industrial and nuclear pollution are poisoning their traditional homelands and food sources.

Altogether, about 150,000 Inuit live in Russia, Alaska, Canada, and Greenland. The Inuit population almost doubled from 1950 to 1970, and it continues to grow. This growth has resulted chiefly from improved health care and better living conditions.

Russia.

About 1 percent of all Inuit live on the northeastern tip of Siberia. They hunt walruses, whales, seals, and other animals and produce carvings and other handicrafts for sale. They receive education, housing, and other benefits from the government.

Alaska.

About 15 percent of all Inuit live in Alaska. Some of them live in towns and cities. But the majority live in small settlements and hunt and fish for most of their food. Some Inuit work in the petroleum or mining industries. However, there is little other industry, so most Inuit in the state are either unemployed or can find only temporary jobs. They depend on the U.S. government for housing and other assistance. The government has greatly expanded the educational programs for Inuit, and more than half of the young people complete high school.

In 1971, the United States Congress passed a bill that gave $9621/2 million and 44 million acres (18 million hectares) of land to Indigenous (native) peoples in Alaska. Congress passed the bill in response to long-standing land claims made by Inuit and other Indigenous people.

Canada.

About 45 percent of Inuit live in Canada. They make up one of the main Indigenous groups in Canada, along with First Nations and the Métis. Most of them live in towns in housing provided by the government. They also receive financial aid, health care, and other help from the government. Many Inuit in Canada cannot find permanent employment. To combat this problem, the government has helped Inuit establish commercial fishing and handicraft cooperatives. These organizations have been especially successful in selling soapstone sculpture and prints, which have become increasingly popular in Canada and the United States. Educational opportunities have increased greatly for Inuit in Canada since the 1950’s, but most Inuit students do not finish high school.

In 1993, Canada’s government passed legislation to create a vast new territory that would have an Inuit majority. The territory, called Nunavut, came into being in 1999. It covers a large part of northern Canada. The government also gave to Inuit title to much of Nunavut’s land.

Greenland.

About 40 percent of all Inuit live in Greenland. Almost all these people have both Inuit and European ancestry. But most experts classify them as Inuit. In 1979, Denmark granted Greenland home rule status. This allows people in Greenland to control the internal affairs of the province, including Inuit affairs.

Most Inuit in Greenland work in towns, chiefly in the fishing industry. Only Inuit in northern Greenland still live mainly by hunting seals and continue many of their traditional ways. Most Inuit in Greenland do not complete high school. Greenland’s government provides them with housing, health care, and other assistance.