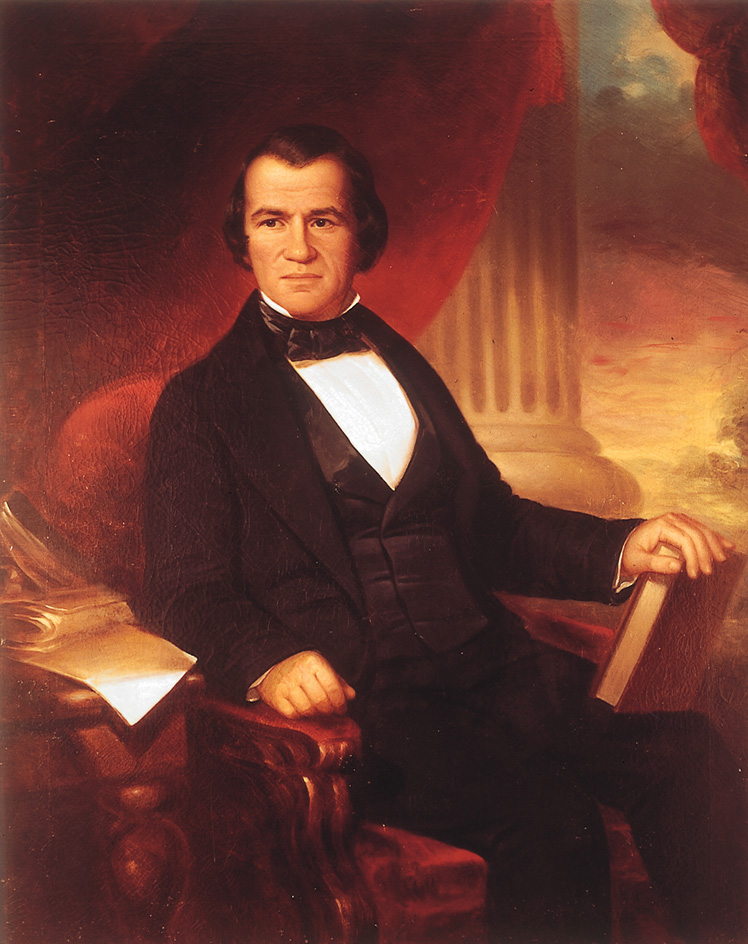

Johnson, Andrew (1808-1875), the first president to be impeached, became chief executive upon the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. The Civil War had just ended. Johnson, a Democrat from Tennessee, inherited the wartime dispute between Lincoln and Congress over how to treat the South after the war. This disagreement soon intensified, as more and more Republicans in Congress came to oppose Johnson’s views. Congress enacted its policies in spite of his repeated vetoes. The division became so wide that the United States House of Representatives voted to impeach him. But the Senate failed by one vote to remove Johnson from office.

Throughout his life, and especially his presidency, Johnson aroused either strong support or fierce dislike. Historians have also been divided in their estimation of him. Some view him as an unfit leader who was too generous to the Southerners after the war. Others have portrayed him as a leader of unusual vision who accurately saw that harsh treatment of the Southern States would increase divisions in the Union. Some scholars believe Johnson’s acquittal in the impeachment trial preserved the independence of the presidency.

The stocky Johnson was a typical man of the frontier. A tailor by profession, he lacked formal schooling and educated himself with the help of his wife. She taught him how to write and do arithmetic. Johnson had the touchy pride of a self-made man.

A serious man, Johnson had limited tact and patience. He reserved humor for family and friends. Johnson lacked Lincoln’s skill in getting people to work together. But he was honest, brave, and intelligent. An unshakable faith in the Constitution guided his actions during his 20 years as a U.S. representative, a governor, and a U.S. senator. One of his lawyers at the impeachment trial wrote: “He is a man of few ideas, but they are right and true, and he could suffer death sooner than yield up or violate one of them.”

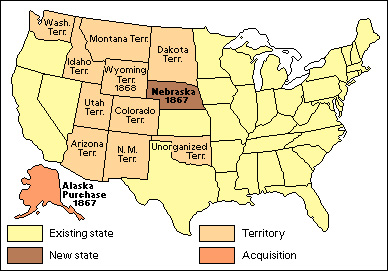

During Johnson’s term, the United States purchased Alaska, and Nebraska became a state. Southerners worked to repair their ruined towns and farms, and to reorganize their economy without slavery. Important “firsts” during this time included the first oil pipeline, practical typewriter, and railroad refrigerator car.

Early life

Boyhood.

Andrew Johnson was born in Raleigh, North Carolina, on Dec. 29, 1808. His father, Jacob Johnson, worked as a handyman in a tavern. Andrew’s mother, Mary McDonough Johnson, was a maid in the tavern. The boy was the younger of two sons. Jacob died when Andrew was only 3 years old. The widow supported her children by sewing and taking in washing.

Tailor’s apprentice.

Andrew’s mother apprenticed him to a tailor when he was 13 years old. The shop foreman probably taught him to read. Tailors usually employed someone to read to the workers as they sat at their tables stitching clothes. Andrew became familiar with the Constitution, American history, and politics through reading newspapers and a few books.

Johnson was supposed to serve as an apprentice for six years. He ran away from home after two years, in part because his youthful pranks were getting him in trouble with the law, and in part because of his independent spirit. Johnson set himself up as a tailor at Carthage, North Carolina, and then at Laurens, South Carolina. He soon moved west into Tennessee to seek a fresh start. Johnson brought his poverty-stricken mother and stepfather to Tennessee in 1826. They settled in Greeneville.

Johnson’s family.

On May 17, 1827, Johnson married Eliza McCardle (Oct. 4, 1810-Jan. 15, 1876), the daughter of a Scottish shoemaker. She taught him to write and to solve simple problems in arithmetic. She also encouraged him to read and to study. The Johnsons had five children.

With hard work and thrift, Johnson built a profitable tailoring business and bought property in town. He was a devoted father who worried about the health, education, and values of his children. Even when away from home on government service, he wrote them letters of advice. There were family tragedies. One son developed tuberculosis, another was an alcoholic, and a third died when thrown from his horse.

Political and public career

Andrew Jackson, a fellow Tennessean and Democrat, became Johnson’s political role model. Both had firm faith in the common people. Johnson was proud of his humble origins. He saw himself as the champion of small white farmers and craftworkers against the great landowners who controlled Tennessee. Soon he attracted a following. Johnson’s powerful voice and quick mind helped him sway large crowds.

Local and state offices.

In 1829, the year Jackson became president, Johnson won his first election. He became a Greeneville alderman along with a tanner and a plasterer. In 1834, Johnson became mayor. In 1835, the voters elected him to the Tennessee House of Representatives. There, he opposed a bill for state assistance in the construction of railroads because he feared dishonesty, monopolies, and wasteful spending. But Johnson represented eastern Tennessee, which needed railroads because of its mountainous isolation. His vote contributed to his defeat for reelection in 1837, the first of only two times in his 45-year political career that he ever lost a popular vote.

Johnson regained his House seat in 1839. In 1841, his district chose him for the state Senate. At that time, Whigs and Democrats had almost equal numbers in the state legislature. Johnson devoted most of his attention to bitter struggles over apportionment and political control of the state.

U.S. representative.

In 1843, Johnson won the first of five terms in the U.S. House of Representatives. In the House, he favored limited spending by the federal government and the lowest tariff rate possible. He favored a revision of the Electoral College to permit direct election of the president and a runoff if necessary. He proposed popular election of senators 62 years before it became part of the Constitution. Johnson often complained about lack of presidential leadership and believed that party considerations counted for more than national issues. He supported the annexation of Texas, the acquisition of California and Oregon, and U.S. involvement in the Mexican War (1846-1848).

The issue of slavery became increasingly important during Johnson’s years in the House. He owned several enslaved laborers who worked as house servants. But Johnson’s votes on slavery questions merely reflected his belief that individuals had a right to own enslaved people and that states had a right to protect the institution. In 1846, he introduced a homestead bill to help poor white settlers obtain public land. Southerners bitterly opposed the bill, knowing that such settlement would add free states to the Union. Johnson’s fight for the bill helped bring him national attention.

Governor.

Johnson ran successfully for governor of Tennessee in 1853. As governor, he favored laws to provide free public education. He also fought unsuccessfully the use of prison labor to compete with free labor. His courage and speaking skill were valuable in the rough and tumble politics of the day.

During his successful campaign for reelection in 1855, he ran against candidates of the Whig and Know-Nothing parties. The campaign was a bitter one, with rumors that Johnson would be shot at a public meeting. As he faced the large, unfriendly audience, Johnson fingered his pistol and declared: “Fellow citizens, I have been informed that part of the business to be transacted on the present occasion is the assassination of the individual who now has the honor of addressing you. I beg respectfully to propose that this be the first business in order. Therefore if any man has come here tonight for the purpose indicated, I do not say let him speak, but let him shoot.” Silence fell. Then Johnson began his speech.

U.S. senator.

In 1857, Johnson returned to Washington as a U.S. senator and continued to push for the Homestead Act. It finally passed in 1862, after the Civil War had begun and Southerners had resigned from Congress.

As the slavery question became more critical, Johnson continued to take a middle course. He opposed the antislavery Republican Party because he believed the Constitution guaranteed the right to own enslaved people. He supported President Buchanan‘s proslavery administration. He also approved the Lecompton Constitution proposed by proslavery settlers in Kansas (see Kansas (“Bleeding Kansas”)). At the same time, he made it clear that his devotion to the Union exceeded his devotion to slavery.

Johnson’s stand in favor of both the Union and slavery might have made him a logical compromise candidate for president. However, he was not nominated in 1856 because of a split within the Tennessee delegation. In 1860, the Tennessee delegation nominated Johnson for president at the Democratic National Convention. But the convention and the party broke up completely, and he withdrew from the race. In the election, Johnson supported Vice President John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky, the candidate of most Southern Democrats.

Johnson believed until almost the last minute that the South would not secede (withdraw) from the Union. In December 1860, he made a powerful speech in the Senate pleading for unity. As for Abraham Lincoln, the Republican candidate who won the 1860 presidential election, Johnson said: “I voted against him; I spoke against him; I spent my money to defeat him; but still I love my country; I love the Constitution; I intend to insist upon its guarantees.”

Johnson stood by his principles when the Southern States started to leave the Union. In March 1861, he denounced the secessionists as traitors. This speech aroused furious opposition in the South. Johnson returned to Tennessee in April, just before a special state election to decide if Tennessee would remain in the Union. Angry mobs stopped Johnson’s train again and again as he traveled across the state speaking against secession. Eastern Tennessee supported Johnson’s position, but the state as a whole voted to secede. The Tennessee militia had orders to arrest Johnson as a traitor, but he escaped. Johnson was the only Southern senator who refused to secede with his state.

Military governor of Tennessee.

Union armies gained a foothold in western Tennessee early in 1862. Then Lincoln appointed Johnson military governor of the state, an unusual position designed to give Johnson extensive civil and military authority. His main task was to organize the loyal Unionists, assure their protection, hold free elections, and restore federal authority in the state.

Johnson’s policy, a mixture of harsh and mild treatment, required Tennesseans to sign an oath of loyalty in order to vote. His policy also required Tennesseans to accept emancipation (freedom) of enslaved people. Johnson had a difficult assignment. He had control over very little territory, and only after final liberation of the whole state from Confederate troops in late 1864 could meaningful elections occur.

Vice president.

Johnson was ideally suited to run as a vice presidential candidate with Lincoln in 1864. He had strongly supported the Union, he was a Southerner, and he was a leading member of the War Democrats. The War Democrats were Democrats who had been loyal to Lincoln throughout the war.

Before the election, Johnson and other War Democrats joined the Republicans to form the Union Party. The Union Party nominated Lincoln for a second term as president and chose Johnson as its candidate for vice president. Lincoln and Johnson won by a large majority. See Lincoln, Abraham (Election of 1864).

Johnson’s inauguration, on March 4, 1865, was a personal disaster. He had recently recovered from an attack of typhoid fever and was still weak. On his way to the ceremony in the Senate, Johnson stopped to rest. He drank some whiskey, thinking it would strengthen him. In the heat of the Senate chamber, and because of his weakened condition, Johnson became tipsy. His jumbled speech embarrassed even his friends. For many years, Johnson’s opponents accused him of drunkenness, but the accusation was unjustified. Lincoln remarked: “I have known Andy for many years; he made a bad slip the other day, but you need not be scared. Andy ain’t a drunkard.”

On April 14, only six weeks after the inauguration, Lincoln was assassinated. The next morning, Johnson took the presidential oath of office in his hotel room.

Johnson’s administration (1865-1869)

At the beginning of his administration, Johnson kept Lincoln’s Cabinet. The government faced the task of restoring the South to the Union. It had to repair the damage of four years of war and determine the place in society of the newly freed Black people. The assassination of Lincoln made these tasks even more difficult. For the background of the period following the war, called Reconstruction, see Reconstruction.

Plans for Reconstruction.

Lincoln had not firmly decided the details of a Reconstruction plan at the time of his death. His wartime plan filled a temporary need but was not adequate for a postwar solution. Lincoln would have expected as a minimum assurances of future loyalty, recognition of the end of slavery, and protection for Southern Unionists and Black citizens. Widely regarded as a moderate, he could favor restricting rebel leaders without desiring punishment.

Most Democrats and many Republicans agreed with Lincoln. But there were many shades of opinion in President Johnson’s party, and the so-called Radical Republicans favored more extreme measures. The Radical leaders included Representative Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania and Senators Charles Sumner of Massachusetts and Benjamin Wade of Ohio. Their main goals were to limit the political power of rebel leaders, to protect formerly enslaved people and plan for their social and economic advancement, and to establish Black suffrage (voting rights). The Radicals regarded Black suffrage as a way to ensure that the Republicans would not become a minority party of the restored Union.

Johnson had often spoken harshly about traitors during the war. Thus, the Radicals thought Johnson would cooperate in their plan for a harsh Reconstruction. But Johnson had also often expressed his belief that the common people of the South had been led into rebellion by the rich and powerful planters. It soon became apparent that he favored generous treatment to all former rebels except military and political leaders.

Congress was not in session when Johnson became president, and so he proceeded with his mild Reconstruction plan. On May 29, 1865, he granted a general amnesty (pardon) to rebels who would sign a loyalty oath, except political and military leaders of the Confederacy and those Southerners whose property had a value greater than $20,000. Even they could apply for special pardons, which Johnson granted regularly. He appointed provisional governors and set forth conditions that the reorganized state governments must meet. But these conditions were minimal because Johnson took a limited view of the goals of the war and what the federal government could require afterwards. Significantly, he left decisions about Black suffrage to the states. In the summer and fall of 1865, the provisional governors carried out their duties, including arranging for the election of representatives to Congress.

Break with Congress.

Many Northerners questioned Johnson’s plan, especially after the beginning of 1866. They doubted the fitness of the Southern States for readmission because of reports of violence against Black Southerners and their white supporters, the passing of laws unfair to Black citizens, and the frequent election of former Confederate leaders. When Congress met in December 1865, it rejected Johnson’s plan and would not seat the newly elected Southern congressmen, and some congressmen criticized Johnson’s plan.

From February 1866 to March 1867, Congress and the president argued over a number of bills designed to replace Johnson’s plan. Congress pushed through, over presidential vetoes, several of these bills. One of them continued the Freedmen’s Bureau, which assisted Black people who had been enslaved. Another, the Civil Rights Act, provided broad federal protection for civil rights. Johnson thought it was wrong to pass such laws when the South was not represented. He believed such subjects were not appropriate concerns of the federal government.

In June 1866, Congress passed the 14th Amendment to the Constitution. This amendment defined American citizenship for the first time. It included Black Americans in that definition. It also laid a basis for far-reaching changes in the relationship of state and federal governments to the individual. In addition, the amendment barred former rebels from holding political office. Johnson strongly objected to the 14th Amendment, though the president has no official function in the constitutional amending process.

Johnson decided to present his view to the people before the congressional elections of 1866. He traveled through the Eastern and Midwestern states. This trip began well for Johnson, but ended badly. The president lost his temper when hecklers tried to break up his meetings. His remarks sometimes lacked dignity and restraint. Newspapers exaggerated the situation, one reporting the president was “touched with insanity … stimulated with drink … .” The elections gave the Radicals a majority in Congress.

Increased tension

developed after March 2, 1867, when Congress passed two laws that Johnson considered unconstitutional. One law was the First Reconstruction Act, which put the Southern States under military rule and established strict requirements for their readmission to the Union. This act also disfranchised the rebels whom the proposed 14th Amendment prohibited from holding office. It did this by barring these people from voting to elect delegates to new state constitutional conventions and from serving as convention delegates. The other law was the Tenure of Office Act. It required Senate approval before the president could fire members of his Cabinet and other officials who had been confirmed by the Senate. Johnson vetoed both of these acts, but Congress repassed them.

On Aug. 12, 1867, Johnson suspended Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, with whom he no longer could work harmoniously. The president appointed General Ulysses S. Grant to Stanton’s office. But Grant was unwilling to hold the office when the Senate would not approve Stanton’s suspension, and Grant allowed Stanton to reclaim the office in January 1868. The president then formally dismissed Stanton and appointed General Lorenzo Thomas. Stanton locked himself in his office and would not allow Thomas to take over. Stanton continued to serve as secretary of war until after Johnson’s impeachment trial.

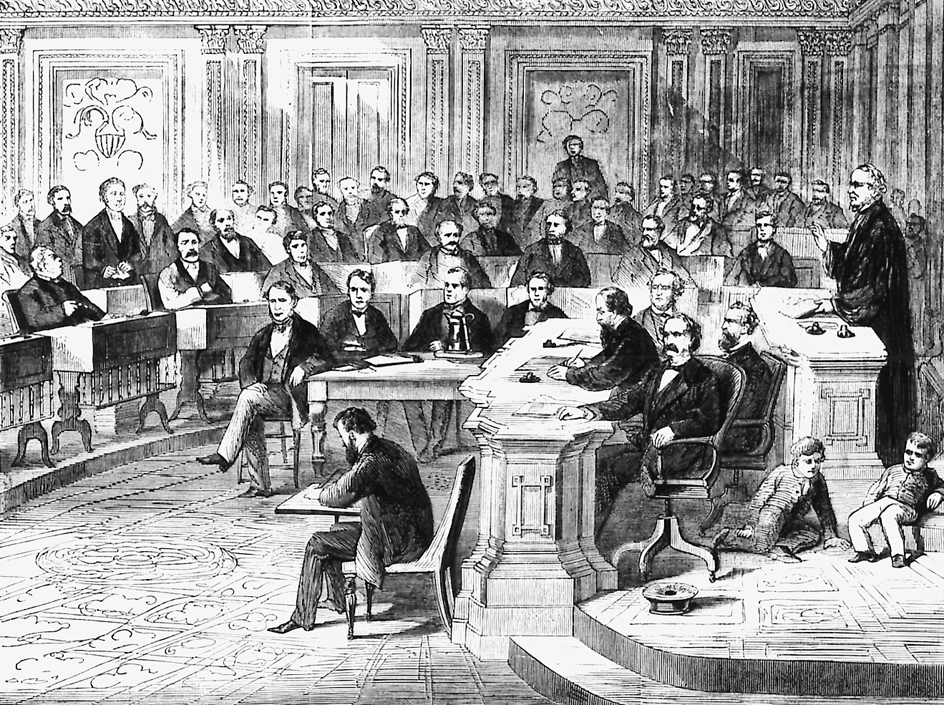

Impeachment

had long been a goal of the Radicals. On Feb. 24, 1868, the House of Representatives voted 126 to 47 to impeach Johnson. On March 2 and March 3, the House adopted 11 articles of impeachment. The most important articles were the first, which charged that the president had violated the Tenure of Office Act by dismissing Stanton, and the 11th, which claimed that he had conspired against Congress and the Constitution. This charge cited Johnson’s claim that Congress did not properly represent all the states.

On March 5, 1868, the Senate organized itself as a court to hear the impeachment. Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase presided. Seven representatives, including Thaddeus Stevens, Benjamin Butler, and George Boutwell, led the attack. A team of lawyers, including Benjamin Curtis and William M. Evarts, defended Johnson, who did not appear at the trial.

The trial

began on March 13, 1868. The galleries buzzed with spectators. Some of Johnson’s accusers tried to implicate him in Lincoln’s murder, but failed. As the trial went on, it became clear that the Radicals had a weak case and were no match for Johnson’s skilled lawyers. Johnson’s defense team argued that Johnson had not violated the Tenure of Office Act because it was unconstitutional and did not apply to Stanton. They emphasized issues over which honest individuals might differ, including whether the act applied to Stanton. This tactic offered the best opportunity to gain the support of senators whose minds were not already made up. Johnson remained calm and made no public speeches.

Conviction required a two-thirds vote, or 36 votes from the 54 members of the Senate. Acquittal required only 19 votes, and Johnson knew he could count on the 9 Democrats and 3 conservative Republicans. He also needed the support of at least 7 of the 12 “doubtful” Republicans. These senators experienced heavy pressure from the public. One Radical supporter warned Senator William Pitt Fessenden of Maine that any Republican senator who votes against the conviction of Johnson “need never expect to get home alive.”

On May 16, the Senate voted on the 11th article. Because it charged a general intent to obstruct the will of Congress, Johnson’s opponents believed it had the best chance of passing. Senator James Grimes of Iowa, stricken with paralysis, came in on a stretcher and voted “not guilty.” The roll call vote lasted over an hour, and the outcome was in doubt until the very end. The final tally of 35 “guilty” and 19 “not guilty” acquitted Johnson by one vote. Ten days later, following the Republican National Convention, the Senate voted on the second and third articles, with the same result. The Senate took no further votes, and the trial was over. The verdict ensured that something more serious than political opposition to Congress would be necessary to justify removing a president from office.

Foreign relations

included two important achievements by Secretary of State William Seward. A French army had overthrown the Mexican government, and Napoleon III named Maximilian of Austria as emperor of Mexico in 1864. In 1865, Seward warned that the U.S. Army would drive out the French by force if necessary. Napoleon recalled his troops in 1867, and Maximilian was overthrown. See Mexico (The French invasion).

Seward’s second accomplishment was the purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867. The Russians feared they might lose the colony to Britain and offered it to the United States for $7,200,000. Seward finally persuaded enough congressmen to vote for the purchase. For many years, Americans called Alaska “Seward’s folly,” little dreaming that it would one day be one of the states. See Alaska (American purchase).

Life in the White House

became livelier during Johnson’s administration than it had been during the gloomy war years. The household included the Johnsons’ two surviving sons, Robert and Andrew; their daughters, Mrs. Mary Stover and Mrs. Martha Patterson; Mrs. Patterson’s husband, Senator D. T. Patterson of Tennessee; and the president’s five grandchildren. The children played and had many parties in the White House.

The president’s wife had been an invalid for many years and lived in quiet seclusion. But her daughter, Mrs. Patterson, was a charming and dignified hostess.

The final months

of Johnson’s administration after the impeachment trial were uneventful. He hoped the Democrats would nominate him for president in 1868. But they chose former Governor Horatio Seymour of New York, who lost to General Ulysses S. Grant.

Johnson’s last important official act was a proclamation on Christmas Day in 1868 of a complete pardon for all Southerners who had taken part in the Civil War and were still unpardoned. He also granted pardons in 1869 to three men still in prison for their part in Lincoln’s assassination. These actions showed Johnson’s desire to end the sectional bitterness dividing the nation.

Later years

After leaving the White House, Johnson remained interested in politics. In 1869, he ran for the U.S. Senate but lost the election by two votes. Assured by friends that bribery would induce two state legislators to change their votes, Johnson indignantly refused. In 1872, Johnson ran for the U.S. House of Representatives as an independent against a Republican and a Democratic ex-Confederate general. For only the second time in his life, Johnson lost a popular election. But he won election to the U.S. Senate in 1875, and thus became the only former president to serve as a senator.

Johnson attended a short special session in March 1875, along with 13 of the 35 senators who voted for his conviction in 1868. Many fellow senators greeted his entrance with applause, and bouquets of flowers decorated his desk.

During a visit to Tennessee, Johnson suffered a paralytic stroke. He died a few days later, on July 31, 1875. Johnson was buried in Greeneville, wrapped in a U.S. flag and with his well-worn copy of the Constitution under his head.