Johnson, Lyndon Baines (1908-1973), like three other vice presidents in United States history, became chief executive upon the assassination of the president. He became president on Nov. 22, 1963, following the fatal shooting of President John F. Kennedy on a street in Dallas. A stunned nation rallied behind the energetic and ambitious new president, a product of the Texas Hill Country.

In 1964, Johnson, a Democrat, was elected to a full term as president. He and Senator Hubert H. Humphrey of Minnesota defeated the Republican ticket of Senator Barry M. Goldwater of Arizona and Representative William E. Miller of New York. They received more than 61 percent of the votes cast—the largest percentage in U.S. history. Johnson chose not to run for reelection in 1968.

Lyndon Baines Johnson had served in Congress for almost 24 years before he was elected vice president in 1960. In 1937, at the age of 29, he won election to the U.S. House of Representatives. He was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1948. Five years later, at the age of 44, he was made Senate Democratic leader—the youngest person ever elected to lead either party in the Senate.

Johnson led the Democratic-controlled Senate during the administration of Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Johnson was powerful and shrewdly mixed the demands of party politics with a sense of cooperation between Democrats and Republicans. He frequently brought about agreement through clever planning and persuasion, which came to be known as the “LBJ treatment.” In his own words, he became known as a “can-do” Senate leader. As president, his image as a master politician caused many people to mistrust him.

After Kennedy’s assassination, Johnson moved with poise and confidence to hold a shocked nation together. He turned his attention to the urgent domestic problems facing the country. He was highly successful in getting Congress to approve many of the social programs Kennedy had proposed, as well as many of his own proposals. The words Great Society became the slogan of the Johnson domestic program.

Johnson’s skill in congressional politics was not enough, however, to overcome the problems raised by the Vietnam War. His failure to explain the deepening U.S. involvement in the war cost him much support and led to a national debate that proved disastrous to his political position. With over half a million U.S. troops in Vietnam in what appeared to be an endless struggle, disagreement at home increased.

Johnson surprised the nation and the world on March 31, 1968, by giving up politics and removing himself as a candidate for a second full term. In a dramatic televised speech, he recognized that he had become the symbol of the unpopular war, as well as other divisions in the country. Johnson said he hoped his withdrawal from the presidential race would help solve these problems.

Although Johnson’s presidency ended in frustration and division, he left a vivid imprint on the nation. He became widely known by his initials, LBJ. His wife, called Lady Bird, and their two daughters, Lynda Bird and Luci Baines, had the same initials. His Texas ranch bore the LBJ brand, and two family dogs were called Little Beagle Johnson and Little Beagle Junior.

Early life

Boyhood.

Lyndon Baines Johnson was born on Aug. 27, 1908, in a farmhouse near the central Texas town of Stonewall. He was the eldest of the five children of Samuel Ealy Johnson, Jr., a farmer and schoolteacher who served five terms in the Texas House of Representatives. His mother, Rebekah Baines Johnson, also had been a schoolteacher. On the day Lyndon was born, his grandfather, Samuel Ealy Johnson, Sr., declared: “He’ll be a United States Senator some day.”

Lyndon had one brother, Sam Houston Johnson (1914-1978). He also had three sisters—Rebekah (1910-1978), Josefa (1912-1961), and Lucia (1916-1997).

Lyndon was an active, healthy child. He liked to hear his mother tell stories from the Bible and from history and mythology. His mother taught him the alphabet before he was 2 years old. He could read at the age of 4.

When Lyndon was 5, his family moved to nearby Johnson City, a town founded by his grandfather. Lyndon attended public school in Johnson City, but he did not like to study. His mother made him do his lessons, however, and he usually made good grades. At the Johnson City high school, he and a friend won a countywide debating competition. A popular boy, Lyndon was president of his class of seven students. In 1924, at 15, he graduated from high school.

Lyndon’s parents wanted him to go to college, but the boy wanted no more studying. He and five friends went to California, camping along the way. They soon ran out of money and separated to find work. Lyndon picked grapes for a short time, then worked as a clerk for his cousin Tom Martin, a lawyer. In the fall of 1925, he rode back to Johnson City with his Uncle Clarence, Tom’s father. There, he found work on a roadbuilding gang.

Lyndon’s parents kept urging him to go to college. Once, after an especially hard day’s work, he told them: “I’m sick of working just with my hands. I don’t know if I can work with my brain, but I’m ready to try.”

College student.

In February 1927, Johnson entered Southwest Texas State Teachers College (now Texas State University-San Marcos). He borrowed $75 from the Johnson City bank to get himself started at college. To pay his expenses, he worked as a janitor. Johnson developed an interest in campus politics, and became the star debater among the students. He often practiced making speeches while sweeping the college halls. He also took a second job as secretary to the college president.

Johnson’s first success in politics came at college. He organized a campus political group called the White Stars. This group took control of campus politics from the Black Stars, an organization dominated by athletes. Johnson also edited the college newspaper and became a leader in other campus activities. He earned excellent grades and made many lasting friendships.

Johnson had to leave college because he ran out of money. He taught school for a year in Cotulla, a small town in south Texas. Then, after saving money from his teaching job, he returned to college. In spite of the year he missed, he was able to finish college in 1930.

After graduation, Johnson taught public speaking and debate in Sam Houston High School in Houston. The debating teams he coached won honors in state contests.

Early political career

Entry into politics.

Johnson entered politics in 1931. That year, Richard M. Kleberg, a Democrat and an owner of the famous King Ranch, ran for the U.S. House of Representatives. Johnson campaigned for Kleberg. The young teacher made speeches and talked to many voters. Kleberg won the special election of November, 1931, and took the 23-year-old Johnson along to Washington as his secretary.

From the start, Johnson impressed the other congressional secretaries. One of them recalled: “Within a few months, he knew how to operate in Washington better than some who had been here for 20 years before him.”

Marriage.

As a congressional secretary, Johnson often visited Texas. On Sept. 12, 1934, at a hearing of the Texas Railroad Commission in Austin, he met Claudia Alta Taylor (1912-2007). Taylor was the daughter of a wealthy family of Karnack, Texas. She had been called “Lady Bird” ever since the age of 2. A nurse gave her the nickname, saying the little girl was “as pretty as a lady bird.”

Johnson asked Taylor for a date immediately after meeting her, but she could not accept. After Johnson returned to Washington, he began to make long-distance telephone calls to her. He also sent her many letters and telegrams. Two months later when he went to Texas again, Johnson proposed to her and she accepted. “Sometimes Lyndon simply takes your breath away,” she said later.

The Johnsons were married on Nov. 17, 1934, and took a honeymoon trip to Mexico. They had two daughters, Lynda Bird (1944-…) and Luci Baines (1947-…).

Youth administrator.

In August 1935, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed the 26-year-old Johnson as Texas state administrator of the National Youth Administration (NYA). Johnson, the youngest NYA state administrator, put about 12,000 youths to work in such projects as playgrounds, roadside parks, and soil conservation. His organization also helped about 18,000 young Americans go through high school or college.

U.S. representative

Election to the House.

Johnson quit his NYA post in 1937 to run for Congress. He ran in a special election to fill the seat of James P. Buchanan of the 10th Congressional District of Texas, who had died. Johnson had nine opponents, many of whom were better known and had more money for campaigning. They were backed by conservatives critical of President Roosevelt’s New Deal program (see New Deal). Johnson supported Roosevelt’s program, including the president’s proposal to reorganize the Supreme Court. Johnson’s opponents charged Roosevelt was trying to “pack” the court with justices who would always favor the New Deal, and they attacked Johnson for favoring the plan. Their speeches gave Johnson valuable publicity.

Two days before the election, Johnson entered an Austin hospital for an emergency operation to have his appendix removed. He was lying in his hospital bed when the election returns came in on the night of April 10, 1937. He had won election to the House of Representatives with almost twice as many votes as his nearest opponent.

When Johnson left the hospital, President Roosevelt was on a fishing cruise in the Gulf of Mexico off the coast of Texas. The president let it be known that he wanted to see the new congressman. Johnson went aboard the presidential yacht at Galveston, then rode through Texas with Roosevelt on the president’s special train. President Roosevelt and the young congressman developed a warm, lasting friendship.

Johnson was sworn in as a U.S. Representative on May 14, 1937. He successfully sponsored many federal projects for his home district. One was a program that provided cheap electricity for farmers under the new Rural Electrification Administration (REA). Johnson also sponsored projects that gave his Texas district soil conservation, public housing, lower railroad freight rates, and expanded credit for loans to farmers. Years later, a friend recalled: “Lyndon was a real pusher. … He didn’t develop his smoothness until later, but he did get things done.” In 1938, Johnson was elected with no opposition to his first full term in the House.

World War II

began in September 1939. As a member of the House Naval Affairs Committee, Johnson helped plan a huge naval air training base at Corpus Christi, Texas. He also helped establish shipbuilding sites at Houston and Orange, Texas ; a Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps at the University of Texas; and a Navy Reserve station in Dallas.

In 1940, Johnson won reelection to the House. Again no one opposed him. During the 1940 election campaign he served as head of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee. The next year, Johnson announced his candidacy for the unexpired term of U.S. Senator Morris Sheppard of Texas, who had died in April 1941. Johnson lost the election to Governor W. Lee O’Daniel, a New Deal foe, by only 1,311 votes. He finished his term in the House.

On Dec. 7, 1941, the Japanese bombed the Pearl Harbor Naval Base in Hawaii. An hour after the United States declared war, Johnson, who had been a member of the Navy Reserve for several years, asked to be called up for active duty. Three days later, Johnson was sworn in as a lieutenant commander, the first congressman to go into uniform.

As a special representative of President Roosevelt, Johnson went to New Zealand and traveled through the Pacific area of operations. He spent several months in Australia with General Douglas MacArthur. After a mission aboard a bomber that was attacked by Japanese fighter planes, MacArthur personally awarded Johnson the Silver Star for gallantry.

In the spring of 1942, while Johnson was overseas, his supporters entered him as a candidate for reelection to the House. He won without opposition. In July 1942, Roosevelt ordered all members of Congress in the armed forces to return to Washington.

U.S. senator

Election to the Senate.

In May 1948, Johnson became a candidate for the U.S. Senate. He was opposed in the primary election by 10 men, including Coke Stevenson, a popular former governor. Stevenson received 477,077 votes to Johnson’s 405,617. However, a runoff election between the two candidates was necessary because Stevenson did not get a majority of the total votes cast. Johnson won the runoff election by only 87 votes.

Johnson took his Senate seat in January 1949. He was appointed to the Senate Armed Services Committee, and became increasingly concerned with the country’s military preparedness in the Cold War with the Soviet Union. After the Korean War began in 1950, he called for more troops and for improved weapons.

In 1951, the Democratic senators elected Johnson as their whip (assistant leader). His chief job was to see that party members were present when a bill came up for a vote. While serving as whip, Johnson increased his ability to persuade people to reach agreement. Democrats noticed a new spirit of party unity.

Minority leader.

Johnson supported Governor Adlai E. Stevenson of Illinois against General Dwight D. Eisenhower in the 1952 presidential campaign. During one three-day period, Johnson made more than 20 campaign speeches for Stevenson. Eisenhower, a Republican, won the election, and the Democrats lost their majority control of the Senate. In January 1953, Senate Democrats unanimously elected Johnson minority leader. At the age of 44, he was the youngest man either party had ever chosen Senate leader.

Johnson came up for reelection in 1954. He won the Democratic primary by a margin of nearly three to one over his closest opponent. In the election campaign, Johnson worked hard for Democratic candidates in many states. The party won control of both houses of Congress, and Johnson was reelected to the Senate.

Majority leader.

Johnson became majority leader of the Senate in January 1955. In this post, he had the responsibility of keeping the legislative process running smoothly. He also decided when various bills would be taken up and who would sponsor the bills.

Skilled in the techniques of give and take, Johnson paved the way for bills before they reached the Senate floor for voting. He checked the views of each Democratic Senator on controversial measures. Johnson delayed Senate voting until he had done everything he could to persuade Senators to vote his way.

In July 1955, Johnson had a heart attack. He spent five weeks in the National Naval Medical Center (now the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center Bethesda) in Maryland, then went to his Johnson City ranch to recuperate. He gave up cigarettes and went on a diet. After he had recovered, he returned to Washington and resumed his post as Senate majority leader.

A strong supporter of the exploration of outer space, Johnson helped establish the Senate Aeronautical and Space Committee, and made himself its first chairman. He also sponsored the law that established the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

In 1957, Johnson put through the Senate the first civil rights bill in more than 80 years. Three years later, in 1960, he beat down a Southern filibuster, and the Senate passed another civil rights measure.

Vice president

Johnson announced his candidacy for the Democratic presidential nomination a week before the party’s 1960 national convention. But on the first ballot at the convention, Senator John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts received 806 votes to Johnson’s 409. Only 761 votes were required, so Kennedy was nominated. Johnson accepted Kennedy’s invitation to run as vice president.

Kennedy’s choice of Johnson as his running mate was intended to attract Southern votes. Kennedy was a liberal Bostonian and a Roman Catholic. Johnson was more conservative, a Southerner, and a member of the Disciples of Christ. In the November election, Kennedy and Johnson narrowly defeated the Republican team of Vice President Richard M. Nixon and Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., of Massachusetts. Johnson was reelected to a third term in the Senate in the same election.

In January 1961, Johnson resigned from the Senate and was sworn in as vice president. He took a more active role in the government than had any previous vice president. He served as chairman of the National Aeronautics and Space Council, the Peace Corps National Advisory Council, and the President’s Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity. Johnson also served on the National Security Council.

President, 1963-1964

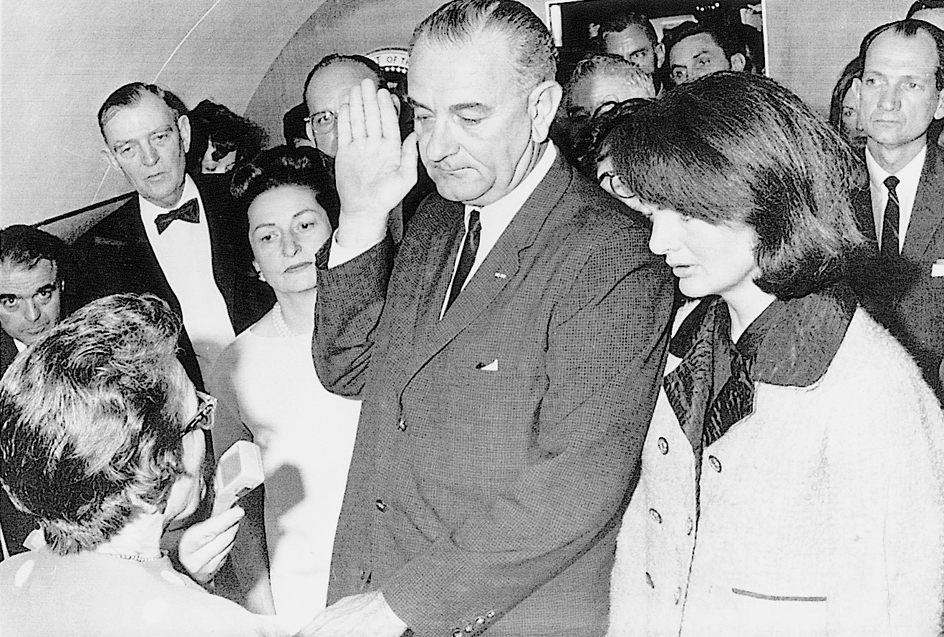

Assassination of President Kennedy.

On Nov. 22, 1963, President Kennedy was assassinated while riding in an open automobile through Dallas, Texas. Governor John B. Connally of Texas, riding in the car with Kennedy, was wounded. Johnson was riding two cars behind the president. After the assassin fired his first shot, a Secret Service agent guarding Johnson shoved him to the floor of the automobile and lay over him.

An hour and 39 minutes after Kennedy died, Johnson was sworn in as the 36th president of the United States. The ceremony took place at 2:39 p.m. aboard the presidential Air Force jet at Love Field in Dallas. At Johnson’s request, the oath of office was administered by an old friend, U.S. District Court Judge Sarah T. Hughes of Dallas. Three minutes after the ceremony, Johnson gave his first order as president: “Now let’s get airborne.” Upon arriving in Washington that night, Johnson told the American people: “I will do my best. That is all I can do. I ask for your help—and God’s.”

Loading the player...Lyndon Johnson on Kennedy's death

Problems as president.

Johnson faced many grave problems as chief executive. The Cold War with the Soviet Union and other Communist countries kept the world in danger of a nuclear war. In Vietnam, Communist rebels fought troops supported by the United States. Racial tension and a high unemployment rate were the main problems that plagued the United States.

Major parts of the administration’s program were bogged down in Congress. The railroad industry was threatened by a crippling strike. Communist agents in Central and South America threatened democratic governments. Anti-American feeling ran high in some areas.

The national scene.

As the first days passed, the country felt the impact of a new, but experienced, leader. Stock values, which had dropped sharply at the news of Kennedy’s death, went back up when the exchanges opened after the funeral. This recovery was accepted as a display of confidence in Johnson.

Legislation.

The president pushed hard for legislation that had been proposed by President Kennedy. He urged quick passage of a tax cut and a strong civil rights bill, both Kennedy measures. He announced a federal budget of less than $98 billion. This was $500 million less than the previous budget, and $2 billion less than most people had expected. Johnson also proposed a national War on Poverty. This program included creating new jobs and building up areas where the economy had faltered. Congress approved the program.

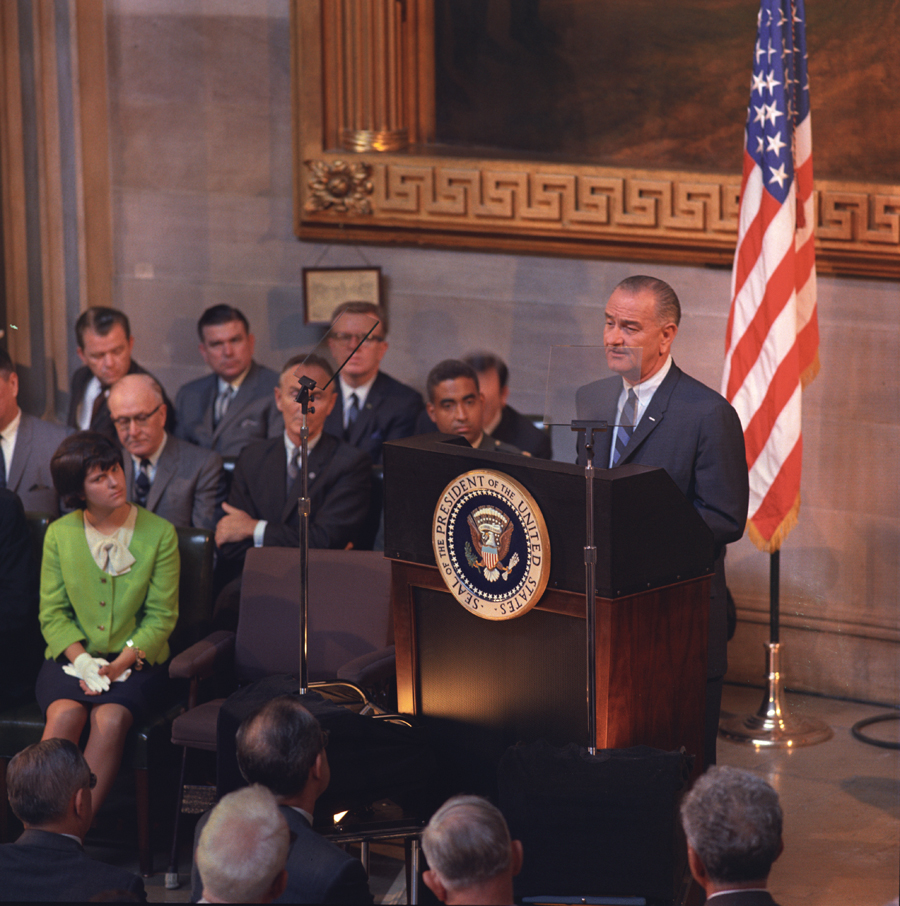

Congress also responded on two other major proposals. It cut taxes for both individuals and corporations, and passed a new civil rights law. Johnson signed the civil rights bill on July 2, 1964. This law opened to Black people all hotels, motels, restaurants, and other businesses that serve the public. The law also guaranteed equal job opportunities for all.

The railroad crisis,

in April 1964, plunged Johnson into one of the toughest U.S. labor disputes. The railroads and the union members who ran the trains had been battling over work rules for almost five years. The companies said outdated rules forced them to hire workers no longer needed. When the companies announced new rules, the unions called a strike.

Johnson arranged a 15-day delay of the strike. He put company and union leaders to work in a room in the White House. Under pressure from Johnson, the two negotiating teams settled the dispute in only 12 days.

Foreign affairs.

Johnson conferred with many of the world leaders who came to Kennedy’s funeral. He stated his basic foreign policy on Nov. 27, 1963: “This nation will keep its commitments from South Vietnam to West Berlin. We will be unceasing in the search for peace; resourceful in our pursuit of areas of agreement even with those with whom we differ; and generous and loyal to those who join with us in common cause.”

Panama

provided the first crisis for Johnson. Early in 1964, anti-U.S. riots broke out in the Canal Zone. Tensions eased after Johnson telephoned Panama’s president and agreed to discuss outstanding problems.

Vietnam.

The United States continued its technical and financial assistance to South Vietnam against the Viet Cong. The Viet Cong were Communist-supported guerrilla forces from South Vietnam. On Aug. 2, 1964, North Vietnamese torpedo boats attacked the U.S. destroyer Maddox in the Gulf of Tonkin. Johnson warned the North Vietnamese that another such attack would bring “grave consequences.” On August 4, Johnson announced that the North Vietnamese had again launched an attack in the gulf, this time against the Maddox and another U.S. destroyer, the C. Turner Joy.

Some Americans doubted that the August 4 attack had occurred, and the attack has never been confirmed. Nevertheless, Johnson ordered U.S. planes to bomb North Vietnam’s torpedo-boat bases. He also asked Congress for powers to take “all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression.” On August 7, Congress approved these powers in the Tonkin Gulf Resolution. Johnson used the resolution as a legal basis for increased U.S. involvement in the war.

The “Whirlwind President.”

Johnson obviously enjoyed being president. He strolled on the White House lawn and chatted with tourists. He met reporters informally. He showed great energy, often speaking several times a day at widely separated places, then going back to his desk in Washington. One reporter called him the “Whirlwind President” during this period.

Johnson’s LBJ Ranch in Texas became an informal White House. He entertained many guests there, and usually gave them big, wide-brimmed Texas hats.

Life in the White House.

Johnson’s two attractive daughters added youthful zest to the White House. Luci liked to invite friends to teen-age dances in the Blue Room. Lynda often cornered her father’s visitors to ask them about current affairs. Mrs. Johnson tried to keep life normal for her daughters, but this was sometimes impossible. For example, Secret Service agents had to accompany the girls on their dates.

Luci was married to Patrick J. Nugent in the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C., on Aug. 6, 1966. She was the first daughter of a president to marry while her father was in office since Eleanor Wilson in 1914. Luci gave birth to a son, Patrick Lyndon Nugent, on June 21, 1967. Lynda was married to Charles S. Robb in the White House on Dec. 9, 1967. Her first child, Lucinda Desha Robb, was born on Oct. 25, 1968.

Mrs. Johnson entertained graciously, and usually included dancing at White House social functions. President Johnson danced with many of the women guests, and he often selected dancing partners for his guests.

Mrs. Johnson added some of the family’s favorite paintings to the White House decorations. Otherwise, she made no changes in what Mrs. Kennedy had done to the mansion. She gave up active direction of the family investments during her husband’s presidency.

Full-term president

In 1964, President Johnson easily won nomination for his first full term. He was nominated on his 56th birthday. He chose Senator Hubert H. Humphrey of Minnesota as his running mate. Their Republican opponents were Senator Barry M. Goldwater of Arizona and Representative William E. Miller of New York.

Johnson won reelection in a landslide. He received 486 electoral votes to only 52 for Senator Goldwater, and Johnson carried 44 states and the District of Columbia.

The Great Society.

The economy boomed during Johnson’s full term. In May 1964, he stated that “… we have the opportunity to move not only toward the rich society and the powerful society, but upward to the Great Society.” The term Great Society caught on, and was used to describe many of the president’s domestic programs. These programs included continuing the War on Poverty, improving the educational system, providing for elder citizens, and aiding urban areas.

Loading the player...Johnson was extremely successful in 1965 and 1966 in getting his proposals passed by the 89th Congress. He was aided by large Democratic majorities in both houses. Congress passed his Appalachia bill, a measure to improve living standards in an 11-state Appalachian Mountain region. It also passed his proposals for increased federal aid to education, a cut in excise taxes, stronger safety measures for automobiles, and the establishment of two new executive departments—the Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Department of Transportation. Medicare, a health insurance plan for the aged, also was passed.

Johnson pushed additional civil rights legislation. In 1965, Congress passed a voting rights law designed to ensure voting rights for Black citizens. Among other things, the law outlawed literacy tests as a voting requirement. The Civil Rights Act of 1968 was designed to end racial discrimination in the sale or rental of houses and apartments. A new housing law, also passed in 1968, provided over $5 billion in federal funds to help the poor buy houses and rent apartments.

The widening Vietnam War

became Johnson’s chief problem. When he became president, U.S. forces in Vietnam consisted of about 16,300 military advisers. In the spring and summer of 1965, he ordered the first U.S. combat troops into South Vietnam to protect U.S. bases there and to stop the Communists from overrunning the country. U.S. planes stepped up bombing attacks against North Vietnam. The number of casualties and the cost of the war mounted. By 1968, there were more than 500,000 U.S. troops in South Vietnam. See Vietnam War.

A bitter debate developed in the United States over the U.S. role in the war. Many Americans became hawks, favoring sterner military action to end the war. Many others became doves, calling for a cutback in the fighting and eventual U.S. withdrawal from the war. Two of the chief critics of U.S. involvement in the war were Democratic Senators Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota and Robert F. Kennedy of New York.

Other developments.

In mid-1965, rebels tried to overthrow the government in the Dominican Republic. Johnson, fearful that Communists were gaining control of the rebel forces, sent U.S. troops to help put down the rebellion. All U.S. troops were withdrawn by mid-1966, after order was restored and elections were held. See Dominican Republic (History).

Johnson named the first Black person to the Cabinet when he made Robert C. Weaver secretary of housing and urban development in 1966. In 1967, he appointed Thurgood Marshall to the Supreme Court of the United States. Marshall became the first Black Supreme Court justice.

Johnson took part in several conferences with other world leaders. In October 1966, he discussed the Vietnam War with six Asian Allied leaders in Manila, Philippines. In June 1967, he met Soviet Premier Aleksei Kosygin in Glassboro, New Jersey, to discuss world problems.

Problems at home

began to increase in 1967. More Republicans were elected to the 90th Congress, and many of them opposed Johnson’s Great Society programs. Some members of Congress said government spending at home should be cut to help absorb the costs of the Vietnam War. Johnson and his supporters said the United States could afford both “guns and butter.” That is, the government could continue programs to help the people at home while paying the war costs. In 1967, Congress slashed appropriations for many of Johnson’s programs. In 1968, Congress voted a temporary surtax in addition to the regular income tax to help pay for the war and check inflation.

Opposition grew to the increasing U.S. role in the Vietnam War, and racial unrest increased. Demonstrations occurred throughout the nation. Riots broke out in the overcrowded ghetto slums of Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Los Angeles, New York City, and Newark. Johnson had to send federal troops to Detroit in July 1967, to stop a riot there. He appointed a special commission of prominent Americans headed by Governor Otto Kerner of Illinois to try to determine causes of the riots. The commission warned that the United States was moving toward two societies, “one black, one white—separate but unequal.”

The war and racial problems at home caused many Americans to question both foreign and domestic policies. Many began to doubt statements by administration officials on the progress of the war. As this credibility gap grew, Johnson’s popularity began to drop. Then Senators Eugene McCarthy and Robert F. Kennedy announced they would oppose Johnson for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1968.

Johnson declines to run.

Johnson shocked the nation by announcing on March 31, 1968, that he would not run for reelection. The president said there was “division in the American house” and that he was withdrawing in the name of national unity. At the same time, he announced a reduction in bombing of North Vietnam.

Loading the player...Lyndon Johnson declines to run for reelection

Johnson’s order to reduce bombing led to talks between U.S. and North Vietnamese representatives. The talks started in Paris on May 13, 1968. Johnson halted all bombing and other U.S. attacks on North Vietnamese territory on Nov. 1, 1968. His action led to peace talks involving the governments of the United States, North Vietnam, and South Vietnam, and a delegation from the National Liberation Front.

Retirement

Johnson retired to his Texas ranch after Republican Richard M. Nixon’s inauguration as the 37th president on Jan. 20, 1969. Later in 1969, Johnson’s birthplace near Stonewall and his boyhood home in Johnson City became part of the Lyndon B. Johnson National Historic Site (now Lyndon B. Johnson National Historical Park).

After leaving office, Johnson avoided active participation in politics. In 1971, he published his memoirs, The Vantage Point: Perspectives of the Presidency, 1963-1969. That same year, the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library opened at the University of Texas in Austin. It holds many of Johnson’s papers and souvenirs.

Johnson suffered a heart attack in April 1972. He slowly recovered and rarely left his ranch. On Jan. 22, 1973, he suffered another heart attack and died. The family cemetery at the ranch, where Johnson is buried, is part of the national historic park. After Johnson’s death, the Manned Spacecraft Center at Houston was renamed the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center. Also, the Texas state Legislature made August 27, Johnson’s birthday, a legal holiday in the state.