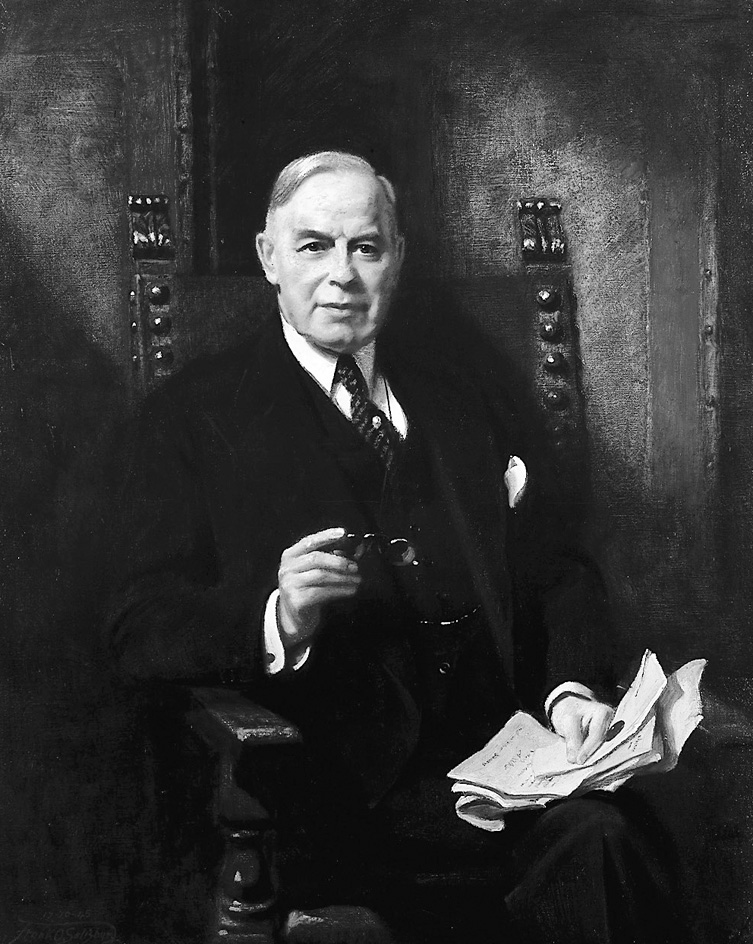

King, William Lyon Mackenzie (1874-1950), served as prime minister of Canada three times between 1921 and 1948. He held the office a total of 21 years, longer than any other prime minister of Canada. He was leader of the Liberal Party of Canada for 29 years.

King guided Canada to independence and equality with other members of the Commonwealth of Nations. He strengthened the unity between English-speaking and French-speaking Canadians, and he skillfully led Canada through World War II (1939-1945).

Mackenzie King devoted almost his entire adult life to his country. As a university student, his research into labor problems brought him to the attention of Liberal Party leaders. He helped organize Canada’s Department of Labour in 1900 and became the first full-time minister of labour in 1909.

King first took office as prime minister in 1921. He served from 1921 to 1926, from 1926 to 1930, and from 1935 to 1948. During his terms as prime minister, King also served as secretary of state for external affairs, except for his last two years in office. His main goals in international relations were independence for Canada and improved cooperation with the governments of the United Kingdom and the United States.

Short, stocky, and shy, King did not look like the great statesman he was. He wanted to be popular, but lacked the personality to inspire public affection. Many Canadians thought King was stuffy and old-fashioned, but they greatly respected his political talents. King, a lifelong bachelor, lived alone and had few close friends. “You can control people better,” he once said, “if you don’t see too much of them.”

Early life

Boyhood.

Mackenzie King was born in Berlin (now Kitchener), Ontario, on Dec. 17, 1874. He was the first son, and the second of the four children, of John King and Isabel Grace Mackenzie King. King’s parents were of Scottish descent and were devout Presbyterians. King was proud of his background and remained a loyal Presbyterian all his life.

“Willie,” as the family called him, had a happy boyhood. He had deep affection for his brother, Macdougall, and his two sisters, Isabel and Janet. When King was about 8 years old, the family moved to a large house called Woodside on the outskirts of town. There he developed a love of the outdoors. He was mischievous and liked to play jokes, but was a serious student.

King’s father was a lawyer and an outstanding speaker. Both parents had a strong interest in current events and discussed them in front of the children. King later recalled: “Any idea I may have had as a boy of entering public life was certainly inspired by the interest which my parents took in political affairs. The story of my grandfather’s struggles in the early history of Ontario fired my imagination. …”

In later life, King liked to contrast the two sides of his family. His grandfather on his father’s side, John King, had been a British Army officer in Canada during the Rebellions of 1837 (see Rebellions of 1837 ). His grandfather on his mother’s side, William Lyon Mackenzie, had led one of the rebellions in the colony of Upper Canada (see Mackenzie, William Lyon ). King claimed he inherited devotion to the British monarch from one grandfather and devotion to the Canadian people from the other. But Mackenzie, for whom King was named, most influenced his life. King’s mother was born in New York, where Mackenzie had been living in exile. She was the dominant personality in the household and gave her son the ambition to clear Mackenzie’s reputation. When King was about 22, he began to sign his name in the way that later became famous: W. L. Mackenzie King.

Education.

In 1891, King entered the University of Toronto. He became known as a good debater. His pals nicknamed him “Rex,” and a few close friends called him that throughout his life. During his senior year, King was one of the leaders in a student strike against school officials. The students refused to attend classes partly to protest the dismissal of a professor who had criticized the administration. The boycott led to an investigation by the government of Ontario.

While in college, King could not decide whether to become a lawyer or a minister. He developed an interest in social work that lasted all his life. King met Jane Addams, founder of Chicago’s Hull House, when she visited Toronto in 1895. His interest in social work grew as she described her settlement house (see Hull House ).

After his graduation in 1895, Mackenzie King worked as a newspaper reporter for a year. He studied law in his father’s office at night, and received his law degree from the University of Toronto in 1896. That same year, King went to the University of Chicago on a fellowship. Jane Addams invited him to live at Hull House, and King eagerly accepted. But he soon found the combination of school and social work too burdensome. He left Hull House to concentrate on his studies. While in Chicago, he completed a thesis that earned him a master’s degree from the University of Toronto.

Life in Chicago’s slums made a deep impression on King. After he returned to Toronto in 1897, he investigated labor conditions there. He found many abuses, and wrote four newspaper articles exposing them.

King found postmen’s uniforms being produced in sweatshops (see Sweatshop ). He indignantly reported this to William Mulock, the postmaster general of Canada. Mulock asked King to recommend ways to protect the clothing workers. King’s suggestions led to the Fair Wages Resolution passed by Parliament.

In 1897, King received a scholarship from Harvard University. He spent two years there and did outstanding work. In 1899, Harvard renewed the scholarship with the privilege of study abroad. King went to London, where he again lived in a settlement house and continued to study social and labor problems.

While visiting Rome in 1900, King received a cable from Mulock. The Canadian government wanted King to be the editor of its new Labour Gazette. King hesitated. He had also been offered a teaching position at Harvard. But he decided to edit the Labour Gazette. The decision changed the course of his life.

Early political and public career

The founding of the Labour Gazette was the first step in the establishment of a Department of Labour in the Canadian government. Postmaster General Mulock was given the added title of minister of labour. On Sept. 15, 1900, King was appointed deputy minister of labour. He was only 25 years old.

King traveled around the country helping to settle labor disputes. He soon earned a reputation for fairness. To some extent, Canada’s industrial relations laws are still based on the Industrial Disputes Investigation Act of 1907, which King drew up.

In 1908, King resigned as deputy minister and ran for Parliament. He won the Liberal nomination in the North Waterloo, Ontario, district where he was born, then won the election. In 1909, Liberal Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier appointed King the first full-time minister of labour. The Liberal government was defeated in 1911, and King also lost his seat in Parliament.

In 1912, King organized the Liberal Information Office and became editor of the party publication, the Canadian Liberal Monthly. Then, about a year later, tragedy struck his family. King’s brother, a doctor, developed tuberculosis and had to give up his practice. His father went blind and had to retire from the practice of law. His mother’s health was failing. King was forced to support the family, though he had little money.

The solution to King’s financial problem came in 1914. The Rockefeller Foundation asked him to direct its Department of Industrial Relations. With his salary, King could care well for his family. While with the foundation, King published his political philosophy in a book called Industry and Humanity (1918). The book, which urges establishment of a welfare state, strengthened King’s reputation as a progressive thinker.

King’s father died in 1916, and his mother died the next year. His brother Macdougall fought his illness bravely, and wrote two books before his death in 1922.

In 1917, Mackenzie King again ran for Parliament. The Liberal leader, Sir Wilfrid Laurier, sided with the French-speaking people of Quebec in opposing World War I conscription (drafting men for military service). King was one of the few English-speaking Liberal former government ministers who stayed loyal to Laurier on the conscription issue, though he was troubled by it. But King was defeated, as were most of Laurier’s other supporters outside Quebec.

Laurier died in 1919. The Liberal Party chose King as leader because he seemed the best person to deal with labor unrest and because he had supported Laurier during the conscription crisis. This made him acceptable to French-Canadian Liberals. King immediately set to work to reunite the English-speaking and French-speaking members of the party. He was elected to Parliament from Prince County, Prince Edward Island, shortly after his election as Liberal leader.

First term as prime minister (1921-1926)

The Liberal Party took control of Parliament after the general election of December 1921. It held 117 out of 235 seats. King became prime minister of Canada on Dec. 29, 1921, succeeding Arthur Meighen, a Conservative.

King took office at a time of falling prosperity. Postwar inflation had driven prices up. The years ahead appeared uncertain. King lowered tariff rates to increase trade. In 1924, the government balanced its budget for the first time since 1913. The government-owned Canadian National Railways, which had been losing money, showed a profit.

King’s outstanding first-term achievement was the enhancement of Canadian self-government in international relations. In 1922, he refused to support the United Kingdom in a possible war with Turkey. In 1923, Canada for the first time signed a treaty alone with another country. This treaty regulated halibut fishing in the Pacific Ocean. At the Imperial Conference of 1923, King successfully opposed British efforts to have a common foreign policy for the entire British Empire.

In the general election of 1925, the Liberals lost ground while the Conservatives gained. King himself was defeated in North York, Ontario, now part of Toronto. But Parliament gave his government a vote of confidence, and he remained prime minister. In February 1926, King ran for Parliament in a by-election in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, and won.

By June 1926, King saw that his government faced defeat in the House of Commons. He advised Governor General Julian Byng to dissolve Parliament and call an election. Byng refused, and so King resigned as prime minister. Conservative Party leader Arthur Meighen formed a government, but he quickly lost a vote of confidence in Parliament. Meighen advised Byng to dissolve Parliament. This time, the governor general did so.

Could a British governor general lawfully refuse the advice of a Canadian prime minister? King made this question the main issue in the election that followed. The Liberals won a substantial victory.

Second term as prime minister (1926-1930)

Mackenzie King again became prime minister on Sept. 25, 1926. He continued his fight for full Canadian self-government at the Imperial Conference of 1926. The conference adopted a report which stated that the United Kingdom and all the self-governing dominions of the Commonwealth had equal status.

The first Canadian federal welfare program began in 1927 with the establishment of old-age pensions. King also favored unemployment insurance but could not persuade the provinces to support it until 1940. A worldwide depression began in 1929. Unemployment became a major problem that Canada was unprepared to fight.

Unemployment became the main issue in the 1930 election, and King’s government was defeated. The Conservatives, under Prime Minister Richard B. Bennett, led Canada for the next five years. By 1935, the depression had taken its toll on Canada. In the election that year, the people probably voted more against Bennett than for King. The Liberals won with the largest majority in Canadian history to that time.

Third term as prime minister (1935-1948)

On Oct. 23, 1935, King began his greatest period as prime minister. The government promoted freer trade to increase employment, and it negotiated major trade agreements with the United States and the United Kingdom. King appointed a Royal Commission to find ways of rebuilding the finances of the provinces.

But foreign affairs overshadowed events at home. King came to realize that a war in Europe was inevitable. He reasoned that if the British became involved in it, English-speaking Canadians would insist on joining them, while French-speaking Canadians would prefer to stay out of the war. King tried to follow a course to ensure Canadian unity if the nation went to war. He was convinced that the decision must be made by Canadians in their own Parliament.

When World War II did come, Parliament almost unanimously supported the government’s decision to participate. Canada declared war on Germany on Sept. 10, 1939; against Italy on June 10, 1940; and on Japan on Dec. 8, 1941.

King skillfully avoided a national crisis over conscription. Most French Canadians still opposed a military draft. To maintain harmony between English Canadians and French Canadians, King side-stepped the issue as long as possible.

In 1942, Canadians voted to release the government from its pledges not to draft soldiers for service overseas. Parliament authorized conscription that same year, but King did not put it into effect. At this time, King uttered his most famous phrase: “Not necessarily conscription, but conscription if necessary.”

By late 1944, the Canadian units overseas, made up entirely of volunteers, badly needed replacements. King then agreed to send draftees overseas, and Parliament supported him. The policy succeeded because of (1) King’s determination to maintain harmony between English Canadians and French Canadians, and (2) the cooperation of most French-speaking representatives in the Canadian government.

King tried to serve as a link between Prime Minister Winston Churchill and President Franklin D. Roosevelt during World War II. He understood the views of both the United Kingdom and the United States. He helped Churchill and Roosevelt reach agreement on some issues.

Canada came out of the war stronger and more united than before. In the 1945 election, King led the Liberals to victory by a narrow margin. The victory was a tribute to King’s success in managing the war, helping increase Canadian industrialization, and preserving Canadian unity during wartime.

After the war, Canada avoided the depression that many had feared. Welfare legislation and increased government spending stimulated the economy. King maintained Canada’s wartime alliance with the United States. He also helped start secret negotiations that led to the signing of the North Atlantic Treaty in 1949.

King’s government also took steps toward making Newfoundland a province of Canada. Newfoundland (now Newfoundland and Labrador) became the 10th province shortly after King retired.

In January 1948, King announced that he would retire that year. He was 73, and his health had been failing. The Liberal Party elected Louis St. Laurent, King’s choice, as its new leader. King made a farewell tour of France and England. While abroad, he became critically ill. King retired as prime minister of Canada on Nov. 15, 1948. However, he remained a member of the Canadian Parliament until April 1949.

Retirement and death

King spent the last year of his life at Kingsmere, his country home in the Gatineau Hills near Ottawa. In his will, King left Kingsmere and his Ottawa home, Laurier House, to Canada. During his last lonely months, King’s health grew steadily worse. He was deeply religious. King also believed in a spiritual world and often tried to speak with the dead, particularly his mother, through séances. King died on July 22, 1950. He was buried in Toronto.