Law is the set of enforced rules under which people are governed. Law is one of the most basic social institutions—and one of the most necessary. No society could exist if all people did just as they pleased, without regard for the rights of others. Nor could a society exist if its members did not recognize that they also have certain obligations toward one another. The law thus establishes the rules that define a person’s rights and obligations. The law also sets penalties for people who violate these rules, and it states how government will enforce the rules and penalties. However, the laws enforced by government can be changed. In fact, laws frequently are changed to reflect changes in a society’s needs and attitudes.

In most societies, various government bodies, especially police agencies and courts, see that the laws are obeyed. Because a person can be penalized for disobeying the law, most people agree that laws should be just. Justice is a moral standard that applies to all human conduct. The laws enforced by government have usually had a strong moral element, and so justice has generally been one of the law’s guiding principles. But governments can, and sometimes do, enforce laws that many people believe to be unjust. If this belief becomes widespread, people may lose respect for the law and, in some cases, disobey it. However, in democratic societies, the law itself provides ways to amend or abolish unjust laws.

This article discusses the main branches of law, the world’s major legal systems, and the methods that democracies use to change their laws. The article also traces the development of law, examines current issues in United States law, and discusses law as a career. There are many separate World Book articles that provide detailed information on topics related to law. For the titles of these articles, see the Related articles list that accompanies this article.

Branches of law

Law can be divided into two main branches: (1) private law and (2) public law. Private law deals with the rights and obligations people have in their relations with one another. Public law concerns the rights and obligations people have as members of society and as citizens. Both private law and public law can be subdivided into several branches. However, the various branches of private and public law are closely related, and in many cases, they overlap.

Private law

is also called civil law. It determines a person’s legal rights and obligations in many kinds of activities that involve other people. Such activities include everything from borrowing or lending money to buying a home or signing a job contract.

The great majority of lawyers and judges spend most of their time dealing with private law matters. Lawyers handle most of these matters out of court. But numerous situations arise in which a judge or jury must decide if a person’s private law rights have been violated. These cases are called lawsuits or civil suits.

Private law can be divided into six major branches according to the kinds of legal rights and obligations involved. These branches are (1) contract and commercial law, (2) tort law, (3) property law, (4) inheritance law, (5) family law, and (6) corporation law. The dividing line between the various branches is not always clear, however. For example, many cases of property law also involve contract law.

Contract and commercial law

deals with the rights and obligations of people who make contracts. A contract is an agreement between two or more persons that can be enforced by law. A wide variety of business activities depend on the use of contracts. A business firm makes contracts both with other firms, such as suppliers and transporters, and with private persons, such as customers and employees.

Tort law.

A tort is a wrong or injury that a person suffers because of someone else’s action. The action may cause bodily harm; damage a person’s property, business, or reputation; or make unauthorized use of a person’s property. The victim may sue the person or persons responsible. Tort law deals with the rights and obligations of the persons involved in such cases. Many torts are unintentional, such as damages in traffic accidents. But if a tort is deliberate and involves serious harm, it may be treated as a crime.

Property law

governs the ownership and use of property. Property may be real, such as land and buildings, or personal, such as an automobile and clothing. The law ensures a person’s right to own property as long as the owner uses the property lawfully. People also have the right to sell or lease their property and to buy or rent the property of others. Property law determines a person’s rights and obligations in such dealings.

Inheritance law,

or succession law, concerns the transfer of property upon the death of the owner. Nearly every country has basic inheritance laws, which list the relatives or other persons who have first rights of inheritance. But in most Western nations, people may will their property to persons other than those specified by law. In such cases, inheritance law also sets the rules for the making of wills.

Family law

determines the legal rights and obligations of husbands and wives and of parents and children. It covers such matters as marriage, divorce, adoption, and child support.

Corporation law

governs the formation and operation of business corporations. It deals mainly with the powers and obligations of management and the rights of stockholders. Corporation law is often classed together with contract and commercial law as business law.

Public law

involves government directly. It defines a person’s rights and obligations in relation to government. Public law also describes the various divisions of government and their powers.

Public law can be divided into four branches: (1) criminal law, (2) constitutional law, (3) administrative law, and (4) international law. In many cases, the branches of public law, like those of private law, overlap. For example, a violation of administrative law may also be a violation of criminal law.

Criminal law

deals with crimes—that is, actions considered harmful to society. Crimes range in seriousness from disorderly conduct to murder. Criminal law defines these offenses and sets the rules for the arrest, the possible trial, and the punishment of offenders. Some crimes are also classified as torts because the victim may sue for damages under private law.

In the majority of countries, the central government makes most of the criminal laws. In the United States, each state, as well as the federal government, has its own set of criminal laws. However, the criminal laws of each state must protect the rights and freedoms guaranteed by federal constitutional law.

Constitutional law.

A constitution is a set of rules and principles that define the powers of a government and the rights of the people. The principles outlined in a constitution form the basis of constitutional law. The law also includes official rulings on how the principles of a nation’s constitution are to be interpreted and carried out.

Most nations have a written constitution. A major exception is the United Kingdom. The constitution of the United Kingdom is unwritten. It consists of all the documents and traditions that have contributed to the country’s form of government. In most democracies, the national constitution takes first place over all other laws. In the United States, the federal Constitution has force over all state constitutions as well as over all other national and state laws.

Conflicts between a constitution and other laws are settled by constitutional law. In the United States, the courts have the power of judicial review, under which they may overturn any laws that are judged to be unconstitutional. A law is declared unconstitutional if the court determines that it violates the United States Constitution or a state constitution. The United States Supreme Court is the nation’s highest court of judicial review.

Administrative law

centers on the operations of government agencies. Administrative law ranks as one of the fastest-growing and most complicated branches of the law.

National, state or provincial, and local governments set up many administrative agencies to do the work of government. Some of these agencies regulate such activities as banking, communications, trade, and transportation. Others deal with such matters as education, public health, and taxation. Still other agencies administer social welfare programs, such as old age and unemployment insurance. In most cases, the agencies are established in the executive branch of government under powers granted by the legislature.

Administrative law consists chiefly of (1) the legal powers that are granted to administrative agencies by the legislature and (2) the rules that the agencies make to carry out their powers. Administrative law also includes court rulings in cases between the agencies and private citizens.

International law

deals with the relationships among nations both in war and in peace. It concerns trade, communications, boundary disputes, methods of warfare, the uses of the ocean, and many other matters. Laws to regulate international relations have been developed over the centuries by customs and treaties.

International laws vary in the number of nations that accept them. Some rules are accepted by all nations as part of international law. These rules cover such items as the sanctity of treaties, the safety of foreign ambassadors, and each nation’s jurisdiction over the air space above its territory. Other rules are accepted by the majority of countries, especially those that are most powerful. International law also includes agreements, such as trade treaties, between two or among a few nations.

There is no uniform way to enforce international laws. Laws within countries provide penalties for those who break them. But in the society of nations, no individual nation has the authority to punish other nations or to force them to submit their disagreements to court. The International Law Commission of the United Nations has given much study to improved ways of formulating and enforcing international law.

Systems of law

Every independent country has its own legal system. The systems vary according to each country’s social traditions and form of government. But most systems can be classed as either (1) a common law system or (2) a civil law system. The United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and other English-speaking countries have a common law system. Most other countries have a civil law system. Some countries combine features of both systems.

Common law systems

are based largely on case law—that is, on court decisions. The common law system began in the United Kingdom hundreds of years ago. The system was called the common law because it applied throughout the land.

The common law developed from the rules and principles that judges traditionally followed in deciding court cases. Judges based their decisions on legal precedents—that is, on earlier court rulings in similar cases. But judges could expand precedents to make them suit particular cases. They could also overrule (reject) any precedents that they considered to be in error or outdated. In this way, judges changed many laws over the years. The common law thus came to be law made by judges.

However, some common law principles proved too precious to change. For example, a long line of hard-won precedents defended the rights and liberties of citizens against the unjust use of government power. The United Kingdom—and the other common law countries—have kept these principles almost unchanged. The United States, Canada, and other countries that were colonized by the United Kingdom based their national legal systems on the common law. In addition, every state in the United States except Louisiana and every Canadian province except Quebec adopted a common law system. Louisiana and Quebec were colonized by France and their legal systems are patterned after the French civil law system.

Case law is still important in common law countries. However, the lawmaking role of legislatures in these countries has increased greatly since 1900. For example, the United States Congress has made major changes in American contract and property law. The changes have dealt, for example, with such matters as labor-management relations, workers’ wages and hours, health, safety, and environmental protection. Nevertheless, common law countries have kept the basic feature of the United Kingdom’s legal system, which is the power of judges to make laws. In addition, constitutional law in these countries continues the common law tradition of defending the people’s rights and liberties.

Civil law systems

are based mainly on statutes (legislative acts). The majority of civil law countries have assembled their statutes into one or more carefully organized collections called codes.

Most modern law codes can be traced back to the famous code that was commissioned by the Roman Emperor Justinian I in the A.D. 500’s. Justinian’s code updated and summarized the whole of Roman law. It was called the Corpus Juris Civilis, meaning Body of Civil Law. For this reason, legal systems that are based on the Roman system of statute and code law are known as civil law systems. This use of the term civil law should not be confused with its use as an alternate term for private law. Civil law systems include both private law and public law.

In civil law countries, which include France and Mexico, the statutes, rather than the courts, provide the final answer to any question of law. Judges may refer to precedents in making their decisions, but they must base every decision on a particular statute and not on precedent alone.

Other systems.

Many countries have patterned legal systems after both civil law and common law. For example, Japan and most Latin American nations have assembled all their private law into a code. But public law in these countries has been greatly influenced by common law principles, especially those that guarantee the rights and liberties of the people.

How laws are changed

Social conditions continually change, and so the law must also change or become outdated. Every nation changes its laws in the manner that its political system prescribes. In a dictatorship, only the top government leaders can change the law. Democracies, however, have developed four main methods of changing the law: (1) by court decision, (2) by legislation, (3) by administrative action, and (4) by direct action of the people.

By court decision.

Judges in common law countries change many laws by expanding or overruling precedents. Especially in the United States, judges often overrule precedents to bring the law into line with changing social conditions. In 1896, for example, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a law that provided for “separate but equal” public facilities for blacks and whites. But in 1954, the Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation in public schools is unconstitutional.

By legislation.

Legislatures may change laws as well as make them. A legislature can change a statute by amending it, by repealing (canceling) it, or by passing a new law on the same subject. In most countries with a written constitution, some form of legislative action is required to amend the constitution.

By administrative action.

Government agencies may be authorized to amend, repeal, or replace the regulations they make. In addition, they may be authorized to interpret old regulations to meet changing conditions.

By direct action of the people.

Some national and many local governments give the people direct power to change the law by referendum or by initiative. In a referendum, a law or a proposed law is submitted to the voters for their approval or rejection. In an initiative, a group of citizens proposes a law, which is then approved or rejected by the legislature or by referendum. Many countries—and most states in the United States—have repealed their constitution one or more times and replaced it with a new one. In most such cases, the new constitution cannot take effect until it has been approved by referendum.

The development of law

Civilized societies are so complex that they could not exist without a well-developed system of law. Scholars therefore conclude that people began to formulate laws in prehistoric times, even before the first civilizations arose. Prehistoric people had no system of writing, and so they left no record of their laws. The earliest laws were customary laws—that is, laws established by custom and handed down orally from one generation to the next.

The first civilizations and first systems of writing appeared between about 3500 and 3000 B.C. The invention of writing enabled people to assemble law codes. The development of written codes made the law a matter of public knowledge and so helped advance the rule of law in society. The first law codes were produced by ancient civilizations in the Middle East.

Early developments in the East.

The first known law codes appeared in the ancient Middle Eastern land of Babylonia. A Mesopotamian king named Ur-Nammu assembled the earliest known code about 2100 B.C. Other Mesopotamian rulers produced codes during the following centuries. A king named Hammurabi drew up the most complete and best known of these codes during the 1700’s B.C. Hammurabi’s code, like the earlier ones, consisted mainly of a long list of rules to settle specific types of cases. The code laid down the law for such matters as the unfaithfulness of a wife, the theft of a farm animal, and the faulty work of a housebuilder. Many of the punishments were harsh by today’s standards. For example, a son found guilty of striking his father had his hand cut off.

From about 1000 to 400 B.C., the Israelites of the Middle East assembled their religious and social laws into a code. The code reflected the teachings of Moses, a great Israelite leader of the 1200’s B.C., and so it is often called the Mosaic Code or the Law of Moses. The Mosaic Code stressed moral principles. It became a key part of the first books of the Hebrew Bible and later of the Christian Bible. According to the Bible, the part of the code known as the Ten Commandments was given to Moses by God. The commandments have had a major influence on the moral content of the law in Western civilization.

By about 500 B.C., the civilizations of India and China had also produced codes of law. The codes in both countries stressed the moral obligations of the law. However, except for the religious laws of the Hebrew people, the legal traditions of Eastern civilizations have had little direct influence on today’s major systems of law. Many Eastern peoples, even those influenced by Western traditions, still stress the moral obligations of the law. Accused persons have little opportunity to defend themselves.

Concern for the rights of an accused person—and for the rights of all citizens—developed mainly in Western civilization. But this development occurred slowly over many hundreds of years. Most scholars regard the ancient Greeks as the founders of both Western law and Western civilization.

The influence of ancient Greece.

Unlike earlier civilizations, the civilization of ancient Greece made the law a clearly human institution. Before the Greeks, most people believed that only gods and goddesses had the power to make laws. The gods and goddesses gave the laws to certain chosen leaders. These leaders passed them on to the people. Like earlier peoples, the ancient Greeks believed that gods and goddesses required human beings to obey the law. But the Greeks also believed that human beings had the power to make laws—and to change them as needs arose. The Greek city-state of Athens became the chief center of this development.

A politician named Draco drew up Athens’s first law code in 621 B.C. It became famous mainly for its harsh penalties for lawbreakers. In the 590’s B.C., the ruling council of Athens authorized a high-ranking official named Solon to reform the city’s legal and political system. Solon repealed most of Draco’s stern code and drew up a much fairer code in its place. Solon also made the Athenian assembly more representative and increased its lawmaking powers.

In time, elected assemblies of citizens gained more and more legislative power in Athens. The Greeks thus began another key development of Western civilization—the founding of democratic government. However, as many as a third of the people of Athens were slaves. The Athenians, like other ancient peoples, denied slaves the legal rights of citizens.

The Greeks believed strongly in the importance of law. They considered respect for the law to be the mark of a good citizen. The great Athenian philosopher and teacher Socrates became the supreme example of this belief. A court sentenced Socrates to death in 399 B.C. for teaching Athenian youths to question the authority of the law. Socrates knew that he was innocent. But he accepted his sentence to show his respect for the law.

Ancient Roman law.

Ancient law reached its peak under the Romans. Roman law included the same basic branches of public and private law that exist today. In fact, the scientific classification of the law began with the Romans. The Romans designed their laws not only to govern the people of Rome but also to build and hold together a vast empire. By the early A.D. 100’s, the Roman Empire included much of Europe and the Middle East and most of northern Africa.

Early Roman times.

The first known Roman law code, called the Laws of the Twelve Tables, was written about 450 B.C. It set down the chief customary laws of the Roman people in a form that was easy to remember. For hundreds of years, Roman boys had to memorize the code as part of their schoolwork.

The principles expressed in the Twelve Tables long remained the basis of Roman law. But the Romans gradually amended these principles to meet changing social conditions. After 367 B.C., a high public official called a praetor made the chief amendments. Each year, the praetor issued an edict (public order) that made any necessary changes. After 27 B.C., the Roman emperor could make or change laws as he wished. Eventually, the whole body of Roman law became extremely complex. The task of interpreting this great mass of laws fell to a group of highly skilled lawyers called juris prudentes, a Latin term for experts in law. Since that time, the science of law has been known as jurisprudence.

For many years, Romans and non-Romans within the empire were governed under different sets of laws. Roman citizens were governed under the jus civile (civil law). The Romans developed a special set of laws, called the jus gentium (law of the nations), to rule the peoples they conquered. They based these laws on principles of justice that they believed applied to all people. Such principles are known as natural law.

Under Roman law, only Roman citizens could own property, make contracts and wills, and sue for damages. Slaves were not citizens, and so they had none of these rights. As the Romans developed the idea of natural law, however, they recognized that slaves also had human rights. Roman law thus began to require that slaves be treated fairly and decently.

Late Roman times.

The belief in natural law also led to the idea that non-Romans within the empire should have the same rights as citizens. In A.D. 212, the Romans granted Roman citizenship to most of the peoples they had conquered, except slaves. The jus civile then became the law of the entire empire.

The principles of natural law set down in the jus gentium remained part of Roman law. These principles were important to future generations because they led to the belief in equal rights for all citizens. But hundreds of years passed before people fully developed the principles of equality that were outlined by the Romans. Once the principles had been developed, they contributed to the building of democratic governments in the United States, France, and many other countries.

Beginning with Julius Caesar, a long line of Roman rulers tried to organize all the empire’s laws into an orderly code. Emperor Justinian I finally completed this task. Justinian’s code, the famous Corpus Juris Civilis (Body of Civil Law), went into effect in 533 and 534. It covered the whole field of law so completely and so skillfully that it later became the model for the first modern law codes. Even today, the codes of most civil law countries are based on Roman law.

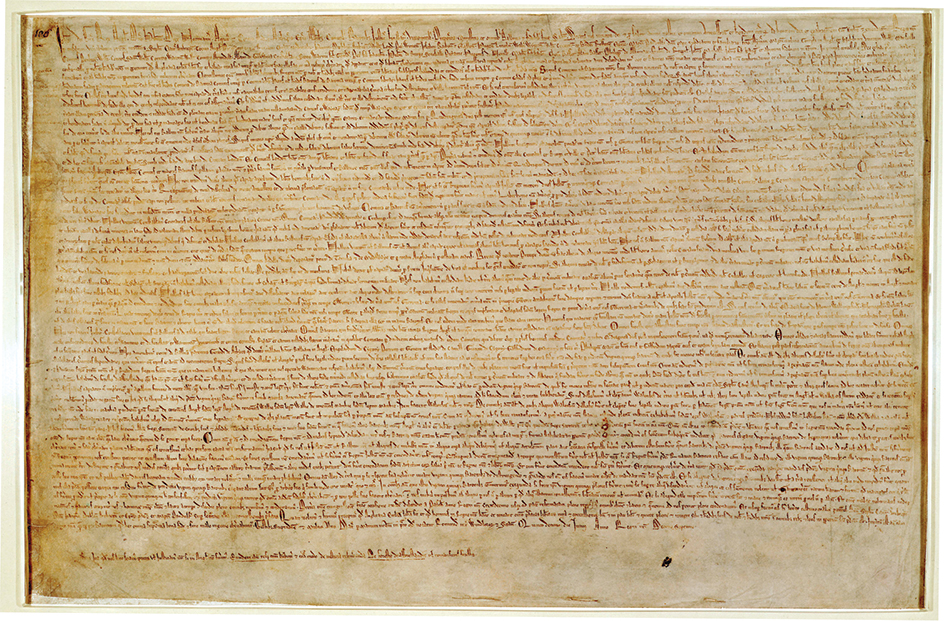

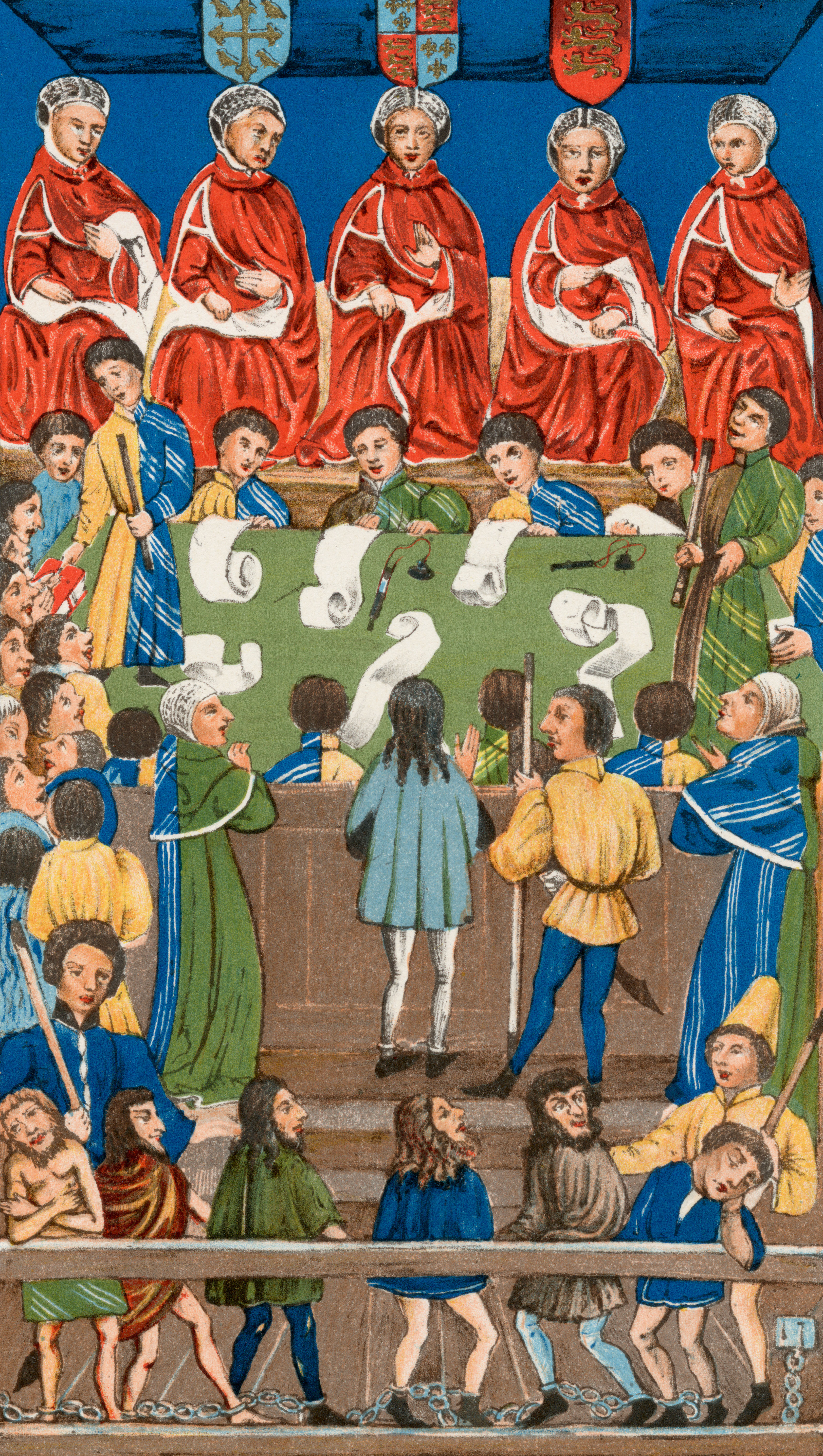

The Middle Ages.

In 395, the Roman Empire split into two parts—the West Roman Empire and the East Roman, or Byzantine, Empire. The West Roman Empire, which had its capital in Rome, broke apart in the late 400’s. In its place arose small kingdoms ruled by the leaders of Germanic tribes. The empire’s fall marked the start of the 1,000-year period known as the Middle Ages. The East Roman Empire, which had its capital in Constantinople (now Istanbul), survived. In 527, Justinian I became the ruler of the eastern empire, and his great code of Roman law was mainly enforced there.

In western Europe, the legal and cultural institutions developed by the Romans, together with the law codes of the Germanic tribes, became the sources for law in the Germanic kingdoms. Roman law also survived in the West as the basis for canon law—the legal system developed by the Roman Catholic Church. Most Europeans during the Middle Ages were Catholics, and so canon law had a powerful influence on their lives.

The Germanic law codes were undeveloped compared with Roman law. They consisted chiefly of long lists of fines for specific offenses, such as stealing a neighbor’s ox or dog.

By the 800’s, many Europeans owed allegiance to individual lords, whose power sometimes rivaled that of the king. Each king or lord enforced the law in his territory and granted protection to the people who served in his armies and who lived and worked on his land. Some historians use the term feudal to describe these relationships. The legal system of the Middle Ages was partly based on the feudal relationships between lords and the people who depended on them.

In particular, feudal law spelled out the duties that people owed to their lord. But a lord could not demand more than the law allowed. The people thus had a right to refuse any demands by their lord that went beyond the limits of the law. Europeans later used this principle to resist monarchs who claimed too much power. The principle thus played an important role in the struggle for democracy in Europe.

By about 1300, Western Europeans had begun to establish improved legal systems. However, this development differed greatly between the countries of mainland Europe and the island country of England.

Developments in mainland Europe.

The economy of Western Europe began to grow rapidly during the 1000’s. As commerce and industry increased, they created a need for a set of laws that was more complex and varied. Scholars believed that ancient Roman law could meet this need. Beginning about 1100, the University of Bologna in northern Italy trained law students from many parts of Europe in the principles of the Corpus Juris Civilis. Interest in the code soon spread to other European universities. Roman law thus gradually began to replace feudal law in mainland Europe.

Developments in England.

England already had a strong, unified legal system by the 1200’s, when Roman law was beginning to spread across Europe. As a result, England did not adopt the Roman system.

England’s legal system had grown out of the country’s courts. English courts had long based their decisions on the customs of the English people. But customs varied from district to district. As a result, similar cases were often judged differently in different districts. In the early 1100’s, however, strong English kings began to set up a nationwide system of royal courts. Judges in these courts applied the same rulings in all similar cases. In this way, the courts soon established a body of common law—that is, law which applied equally anywhere in England. Judges could change the law as the nation’s needs and customs changed, but any change applied in all common law courts.

As English common law developed over the years, it established many precedents that limited the powers of government and protected the rights of the people. These precedents made even the monarch subject to the law. The common law thus assisted the growth of democracy in England.

The right known as habeas corpus was one of the chief common law safeguards of personal freedom. Habeas corpus is a Latin term meaning you are ordered to have the body. As developed in English common law, habeas corpus means that a person cannot be held in prison without the consent of the courts. The Founding Fathers of the United States considered this right so essential to human liberty that they wrote it into the Constitution (Article I, Section 9).

The first modern law codes.

Roman law had been adopted throughout most of Europe by the end of the 1500’s. But only England had a monarchy strong enough to establish a unified legal system. In other countries, law codes were drawn up and enforced mainly by local governments. These local codes differed greatly from one part of a country to another. Beginning in the 1500’s, many European monarchs set out to form strong central governments. To help achieve this goal, they began to assemble the assorted local codes of their countries into national codes—a development called the codification movement.

The codification movement reached its peak under the French ruler Napoleon Bonaparte. In 1800, Napoleon appointed a committee of legal scholars to turn the whole of French private law into a compact, well-reasoned code. The new code, called the Code Civil or Code Napoleon, was a skillful blend of Roman law, French customs, and democratic philosophy. It went into effect in 1804, along with several other codes that covered other areas of law, and has remained France’s basic code of private law ever since. It has also been a model for the private law codes of most civil law countries. Thus, Roman law, as contained in the Code Napoleon, still influences people’s lives.

Beginnings of U.S. law.

When the American colonists declared their independence from England in 1776, they based their claims partly on the ancient Greek and Roman ideas of natural law. These ideas had been developed in detail by various French philosophers of the 1700’s, such as Claude Helvetius and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. The French had especially promoted the idea that the natural law gives all people equal rights. The U.S. Declaration of Independence echoed this idea in the famous phrase “… all men are created equal [and] are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights.”

The American colonists also based their claims for independence on common law principles. The English settlers who established the American Colonies had brought these principles with them. Moreover, many of the leaders in the colonies’ struggle for independence were lawyers who had been trained in the common law. These men were especially dedicated to the common law principles that put the rights of the people above the will of a monarch. The common law thus became a driving force behind the writing of the Declaration of Independence. Common law principles also influenced the development of the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

Constitutional law.

American courts had the same power to make laws that English courts had. A series of U.S. Supreme Court decisions in the early 1800’s strengthened this power. The court’s decision in 1803 in the case of Marbury v. Madison was especially important. In this decision, the court declared a federal law unconstitutional for the first time. The principle of judicial review was thus firmly established, enabling U.S. courts to overturn laws they judged unconstitutional.

Other branches of law.

The U.S. legal system adopted the basic ideas, but not the whole body, of English common law. Many parts of the common law were impractical for the new, rapidly expanding nation of the United States. English property law was particularly unsuited. Land was scarce in England, and so the law heavily restricted the transfer of land from one owner to another. But much of the land in the United States was unsettled, and the nation was constantly expanding its frontiers. To ensure the nation’s growth, people had to be free to buy and sell land. American property law therefore began to stress the rights and obligations involved in land transfers. The English laws that restricted such transfers were discarded.

Contract law became more important in the new nation than it had been in England. By the early 1800’s, Americans had begun to develop a flourishing economy based almost entirely on free enterprise. In a free enterprise system, business people regulate their dealings largely by contract. The rapid growth of the U.S. economy in the 1800’s therefore brought an enormous increase in contract law. The law especially emphasized freedom of contract, with no government interference. This emphasis lasted into the 1900’s. In 1905, in the case of Lochner v. New York, the Supreme Court upheld the right of employer and employee to contract for working hours free from government control.

The development of Canadian law.

Canada’s legal history dates from the legal system established by the first French settlers in the 1600’s. The French set up a civil law system in the areas they colonized, including what is now the province of Quebec. They based their system on one of the major local law codes in France—a code known as the Custom of Paris.

Britain gained control of France’s Canadian possessions in 1763 and introduced a common law system. But French Canadians objected to giving up their legal traditions. In 1774, the British Parliament passed the Quebec Act, which allowed French Canadians to follow their traditional system in private law matters. The common law, however, remained the basis of all other law in Canada. In 1866, Quebec adopted a private law code based on the Code Napoleon.

The British North America Act, passed by the British Parliament in 1867, created the Dominion of Canada. The act gave Canada limited self-government and provided a constitutional framework for the new Canadian federal government. The federal legal system was based on the common law. Each province could keep its traditional legal system except in matters of public law. All the provinces except Quebec based their legal system on the common law. Quebec kept its civil law system in matters of private law. Canada’s Parliament was authorized to set up the nation’s criminal law system.

Law since 1900.

During the 1800’s, Western systems of law spread throughout the world. Many countries, for example, adopted private law codes patterned after the Code Napoleon. The U.S. Constitution influenced the making of written constitutions in many countries. The main systems of law—that is, the civil and common law systems—have remained basically unchanged since 1900. However, the role of the law has undergone dramatic changes in nearly every country.

Freedom of contract was the key doctrine of private law in many countries until the 1900’s. By then, many businesses were using this freedom to increase their profits at the expense of their employees, stockholders, and customers. For example, factory owners claimed that efforts to protect the rights of workers interfered with the owners’ rights to contract freely with their employees. Many employees had to accept unfavorable contracts or lose their jobs.

Before 1900, the idea that law should interfere with private business as little as possible was widely accepted. Since then, however, the public’s attitude toward the law has changed greatly. Today, most people believe that the private interests of some members of society should not deprive other members of society of their rights. Legislation and court decisions in the United States and other countries have reflected this belief, especially by stressing the social aspects of contract law. For example, the U.S. Congress and the state legislatures have passed many laws to help ensure the fairness of employment contracts. Some of these laws regulate working conditions and workers’ wages and hours. Other laws guarantee the right of workers to organize and to strike.

Legislation and court decisions have also changed many features of property, tort, and family law in many countries since 1900. The social obligations of property owners have been enforced by zoning laws and by laws prohibiting environmental pollution. During the 1800’s, tort law typically held that a person could collect compensation for an injury only if another person could be proved at fault. But the development of private and public insurance programs during the 1900’s helped establish that a person should be paid for accidental injuries regardless of who was at fault. This “no fault” principle has made it unnecessary to sue for damages in certain cases. Many changes in family law during the 1900’s reduced the legal rights of husbands over their wives and of fathers over their children. The law thus placed increased emphasis on women’s and children’s rights.

During the mid-1900’s, the United States and other countries gave increased attention to the field of civil rights. For instance, during the 1950’s and 1960’s, the U.S. Supreme Court used the power of judicial review to strike down a variety of state and local laws that supported racial segregation. The court based these decisions on the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, which guarantees equal protection under the law. Since 1970, the court has also used this amendment to help ensure fair and equal treatment for women, aliens (noncitizens), poor people, and persons accused of crime.

Developments in international law.

During the 1900’s, international law became increasingly important. After World War I ended in 1918, the governments of 32 nations drew up a peace settlement that led to the establishment of the League of Nations. The goal of the League of Nations was to prevent war and uphold international law. In 1920, the League set up the Permanent Court of International Justice. From 1928 to 1934, more than 60 nations signed the Kellogg-Briand Pact, under which they agreed not to use war to achieve their goals. However, both the League of Nations and the Kellogg-Briand Pact were largely unsuccessful in upholding international law.

Shortly after World War II ended in 1945, the United Nations (UN) was formed to work for world peace and security. The trials of German and Japanese leaders at Nuremberg and Tokyo after World War II were an important step in the development of international law. Some of the leaders were charged not only with breaking the laws of war, but also with causing the war. In the 1990’s, the UN began conducting trials of people accused of committing war crimes—that is, violations of the rules of war—in civil wars in Rwanda and in the lands that had been part of Yugoslavia.

Many other international organizations and agreements have shaped international law overseeing various economic, cultural, and social concerns. These agreements and organizations include the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). NAFTA united Canada, Mexico, and the United States in one of the world’s largest free-trade zones. It was later updated in a version called the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). ASEAN works for peace and stability among the countries of Southeast Asia.

Current issues in U.S. law

The problem of too many laws.

Congress and the state legislatures pass thousands of laws each year. These laws are added to the hundreds of volumes of federal and state statutes already in force. The regulations issued by federal and state agencies also accumulate at a rapid rate.

As the number of laws has grown, the whole body of law has become more difficult to administer. In addition, the law has become so complex that people cannot possibly know how it affects them in every case. A nation can make its laws simpler by organizing them into a uniform code. But common law traditions are so strong in the United States that all efforts to codify the nation’s private laws have failed.

The enormous number of laws issued each year raises the question of whether society expects too much of the law. Many people believe that nearly every need and want of society can be met simply by “passing a law.” This belief has led legislatures and the courts to make more laws to satisfy not only society’s demands but also the demands of small special-interest groups. However, there are limits to what the law can do. If the law tries to satisfy every demand, it can easily fail. People may then begin to doubt that the law can do anything at all. In addition, people tend to resent laws that interfere in their private affairs. As the number of laws grows, more and more aspects of life become regulated.

The question of who should make laws.

The common law as developed in England enables the courts to make laws. However, American courts have expanded their powers far beyond the English idea in order to bring about revolutionary social changes, especially in the field of civil rights. Some of these changes have been unpopular with many Americans. But through the power of judicial review, the courts can overrule the wishes of even the vast majority of the people.

Many experts believe that questions of great social importance should be settled by legislation rather than by decisions reached in courts. They point out that democratic government depends on the freedom of the legislature to reflect the will of the people. If the courts block this freedom, democracy may be seriously weakened. Other experts believe that the courts must defend the constitutional rights of every American regardless of popular support.

The right to legal assistance.

As the law has grown more complex, the demand for professional legal services has increased. As a result, even the most routine services, such as drawing up contracts and wills, have become more costly. Large corporations and wealthy people generally can afford all the legal help they need.

Since the early 1960’s, court decisions and legislation have ensured legal help for criminal defendants too poor to hire a lawyer. In addition, public and private legal aid services provide poor people with free counsel in private law cases. Still, many poor people do not know they have a right to these services, and so they do not benefit from them.

Millions of middle-income Americans have great difficulty getting professional legal help when they need it. These people cannot afford to hire a lawyer. Yet they do not qualify for the free legal services available to the poor. To help remedy this problem, some lawyers in large cities have set up legal clinics. The clinics provide middle-income families with routine legal services at reduced rates.

Social obligations and individual rights.

Court decisions and legislation have increasingly stressed the social aspects of the law in the United States. More and more laws have thus been made to ensure equality for all Americans and to protect the economic and environmental interests of society. To achieve these goals, the law has had to limit many of the rights traditionally granted to individuals under private law. Property rights and freedom of contract, in particular, have been heavily restricted—a matter of concern to many Americans.

Most experts believe, however, that the social trend of the law will continue. If it does, the rights and freedoms of individuals under private law will become even more restricted. Legislatures and courts therefore face an enormous challenge. On the one hand, they must formulate laws to meet the needs of a complex and rapidly changing society. On the other hand, they must also be careful that these laws do not so restrict property rights as to hinder free enterprise.

A career as a lawyer

In most countries today, a person must be trained and licensed to practice law. However, the training and licensing of lawyers vary greatly from country to country. In the civil law countries of Western Europe, Japan, and elsewhere, students study law as undergraduates and then apply for further specialized legal study at a national legal research institute. These institutes provide training and apprenticeships in specific areas of law. By contrast, legal education in the United States takes place at law schools, where students receive a more general training in all areas of law. This section deals with law as a career in the United States.

Law education.

To practice law in most states of the United States, a person must first have a degree from a law school. The majority of law schools are a part of large universities. A few are independent institutions. Most U.S. law schools admit only four-year college graduates. During their college training, prelaw students do not have to take any particular courses. But the majority of students planning to go to law school specialize in the humanities or the social sciences.

Most law school programs require three years of study. During this time, students take courses in all the major branches of public and private law. Upon completing the program, a student receives a J.D. (Doctor of Jurisprudence) degree. In general, law schools at state universities in the United States have the lowest tuition fees, and private institutions require the highest.

The first U.S. institution devoted entirely to the teaching of law operated in Litchfield, Connecticut, from 1774 to 1833. The first law professorship in the United States was established in 1779 at the College of William and Mary. Harvard University established the nation’s first university law school in 1817. Between 1830 and 1860, law schools were founded at other U.S. universities, including Columbia University, the University of Michigan, New York University, Northwestern University, the University of Pennsylvania, and Yale University.

All the early law schools used traditional teaching methods. Students attended lectures and studied standard textbooks. During the 1870’s, a new method of teaching law, the case method, was developed at Harvard University. This method trained students in precise legal reasoning through the reading, analysis, and discussion of actual court cases. Today, almost all U.S. law schools use the case method.

Law school standards have been steadily raised in the United States since the mid-1800’s, largely through the work of the American Bar Association (ABA) and the Association of American Law Schools (AALS). The ABA is a private, nationwide organization of lawyers that was founded in 1878. The AALS was founded in 1900 by 35 of the about 100 U.S. law schools that were then in existence. Both organizations have continually raised the minimum educational standards that a law school must meet to gain their approval. Today, the United States has about 200 law schools approved by the ABA.

In the past, nearly all law students were men. But the number of women law students has been steadily increasing. Today, women make up about half the total enrollment in the major U.S. law schools.

Licensing of lawyers.

Each state has its own bar—that is, the body of lawyers who have a license to practice in the state. The word bar originally referred to the railing or partition that traditionally separates spectators from the proceedings in a courtroom. Lawyers represent their clients before the bar rather than from the spectator area in the back of the courtroom. Because of the lawyer’s position in the courtroom, the whole body of lawyers became known as the bar.

Most states issue a license to law school graduates who pass the state’s bar examination. A few states automatically license graduates of approved law schools in the state, without a bar examination. The highest court or the legislature in each state sets rules of conduct for lawyers. The court has the power to disbar (suspend from practice) any member of the state bar who violates these rules.

The practice of law.

The majority of U.S. lawyers conduct most of their business out of court. But some lawyers, particularly those who specialize in criminal cases, do much trial work.

Many American lawyers have a general practice. They provide every kind of legal service, from drawing up wills and other legal papers to handling court cases. Other lawyers—especially in big cities—concentrate on a particular branch of the law, such as corporation law or administrative law. Some of these lawyers work for large law firms. Such firms provide clients with specialized services in one or more branches of the law. Most large business corporations employ experts in corporation law.

Some large law firms have begun to employ specially trained persons called lawyer’s assistants. A lawyer’s assistant does paralegal work—that is, routine legal tasks under a lawyer’s supervision. Lawyers who employ such assistants can devote more time to complex legal cases.

The law has long been one of the most common roads to public office. Congress, the state legislatures, and the administrative agencies have attracted more people from the law than from any other profession. Almost all judges have been lawyers, and such public officials as district attorneys and prosecutors must be lawyers. About three-fifths of all the presidents of the United States have been lawyers. Further information on careers in the law can be obtained by contacting the American Bar Association, which has its headquarters in Chicago.