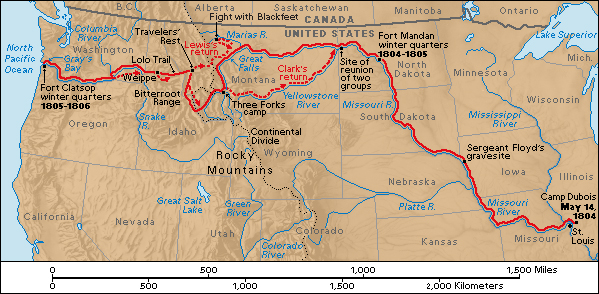

Lewis and Clark expedition was an exploration of the vast wilderness of the northwestern United States. The United States government sponsored the expedition. United States Army officers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark served as co-leaders. The Lewis and Clark expedition began near St. Louis in May 1804 and returned there in September 1806. Historians often refer to the explorers as the Corps of Discovery. Lewis called them the Corps of Volunteers for North Western Discovery. In time, the group became known simply as the Lewis and Clark expedition.

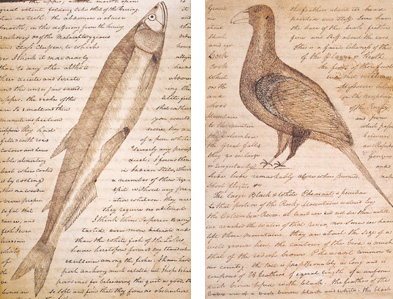

The expedition traveled a total of about 8,000 miles (12,800 kilometers). Starting from a camp near St. Louis, the group journeyed up the Missouri River. They crossed the Rocky Mountains and traveled down the Columbia and other rivers to the Pacific coast. The explorers returned to St. Louis with maps of their route and surrounding regions. They brought specimens and descriptions of plant, animal, and mineral resources. They also gathered information about Indigenous (native) American cultures. The expedition’s success enabled the United States to claim the Oregon region. The region included what are now the states of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho.

The Lewis and Clark expedition was a remarkable achievement by a band of brave, determined, and skillful explorers. The group crossed half the continent of North America. They traveled through a largely unknown wilderness on foot, on horseback, and by boat. They faced scorching and freezing weather. They moved through swift river currents and rugged mountain trails. They met dangerous animals. At times, they suffered from hunger and exhaustion. But the group returned safely home with a wealth of information. The expedition’s journey ranks as one of the greatest adventure stories in United States history.

Planning the expedition

Jefferson’s plans.

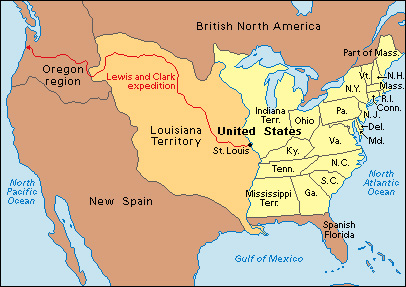

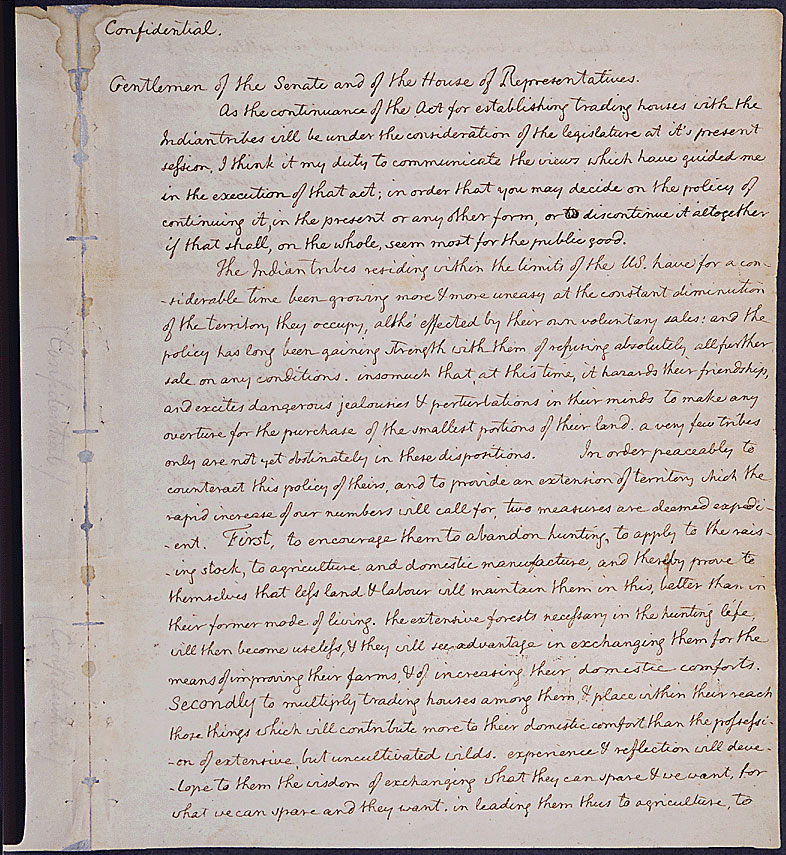

Within a year after Thomas Jefferson became president of the United States in 1801, he began to plan an expedition through the Louisiana Territory and the Oregon region. The Louisiana Territory was a huge area owned by France. The territory lay between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains, stretching from the Gulf of Mexico to Canada. The Oregon region included a large area between the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific coast. Spain, Russia, and England claimed parts of the region. Jefferson believed that a route to the Pacific coast along the Missouri and Columbia rivers could form part of a land-and-water passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

The president’s plan included gathering scientific information about the Louisiana Territory and the Oregon region. He also hoped to establish communication with the local Indigenous peoples. The plan expanded after May 2, 1803. At that time, U.S. representatives signed a treaty with France to buy the Louisiana Territory. Then the expedition received the additional tasks of tracing the boundaries of the territory and laying U.S. claims to the Oregon region.

Jefferson chose Meriwether Lewis to lead the expedition. Lewis was a U.S. Army captain and Jefferson’s private secretary. Lewis, in turn, selected William Clark, a former U.S. Army officer, to join him in leading the expedition. Lewis had served under Clark in the Army. Clark had resigned from the Army in 1796 but reenlisted in 1803 to join the expedition. When Clark reenlisted, he received the rank of lieutenant. This rank was below that of Lewis. But members of the expedition regarded Clark as a co-leader and addressed him as captain. Both Lewis and Clark had wilderness experience. Both had served in Indian wars—that is, Army campaigns against Indigenous groups. In addition, Clark had considerable mapmaking skills. Lewis had some training in the study of animals and plants.

Preparation.

During the summer of 1803, Lewis spent time studying in Philadelphia. He learned how to classify plants and animals. He also mastered how to determine geographical position by observing the stars. He then went to Pittsburgh. In late August, he left the city in a large flat-bottomed boat called a keelboat. Clark, meanwhile, began to recruit members of the expedition. The explorers chose skilled woodsmen and hunters. The members were accustomed to manual labor and military discipline. Most of the men were soldiers. The party also included York, a resourceful Black man who had worked as a slave for the Clark family since childhood. The lone pet in the expedition was Seaman, a Newfoundland dog owned by Lewis.

In December 1803, the party set up winter quarters at Camp Dubois (Camp Wood). The camp lay across the Mississippi River from St. Louis in present-day Illinois. There, Lewis and Clark trained their men. They also learned from fur traders and travelers about the regions the party would explore.

Journey to the Pacific

Up the Missouri.

On May 14, 1804, the expedition set out from Camp Dubois in the keelboat and two canoes. The group numbered about 50 men. Many were French boatmen temporarily hired to move the heavy keelboat and other craft against the Missouri’s swift current. The men moved the keelboat by pushing poles against the river bottom or by pulling the boat with ropes from shore.

The keelboat carried a large amount of supplies. The gear included food, medicine, scientific instruments, and weapons. Lewis and Clark also took many presents for Indigenous people they expected to meet. These gifts included brass kettles, brightly colored cloth, colored beads, ivory combs, knives, pipes, pocket mirrors, scissors, sewing needles and thread, silk ribbons, and tobacco.

The beauty of the land and its abundant wildlife amazed Lewis and Clark as they traveled up the Missouri. The first tragic event of the expedition occurred on August 20. Sergeant Charles Floyd died from what may have been a burst appendix. The explorers buried Floyd near present-day Sioux City, Iowa. He was the only member of the group to die on the journey.

In September, the explorers had a tense encounter with the Teton Sioux people. After the explorers had talked and exchanged gifts with them, the Sioux refused to allow Clark to return to the boat. They let him go only after they saw that the soldiers in the party were preparing to fight. Most meetings with Indigenous people, however, were friendly. Indigenous people often helped the men by describing the way ahead and by providing food. Indigenous groups the explorers met early in the expedition included the Oto, Yankton Sioux, and Arikara.

When Lewis and Clark talked with Indigenous people, they spoke about President Jefferson. One of the expedition members, Sergeant Patrick Gass, described the basic speech in his diary. He noted that the two captains told the Indigenous people that all the “Red children were now under the protection of a new father, the Great White Father at Washington. They must keep the peace. The Great White Father would send traders to supply them with all necessities.”

In October, the expedition reached the villages of the Mandan and Hidatsa peoples near what is now Bismarck, North Dakota. The expedition established its winter camp, Fort Mandan, near the Indigenous villages. At that time, the population of the villages totaled about 4,500—about three times the population of St. Louis.

During the winter, the French-Canadian trader Toussaint Charbonneau and his Shoshone wife Sacagawea << sah `KAH` guh WEE uh >> joined the expedition. The explorers hired the couple mainly to help interpret Indigenous languages. At the winter camp, Lewis and Clark brought their diaries and maps up to date. They also wrote about the Indigenous peoples they had encountered. Some of the explorers joined the Mandan on buffalo hunts.

West to the Rockies.

The journey resumed on April 7, 1805. Part of the group started back to St. Louis with the keelboat. The boat was loaded with maps, reports, and animal, plant, and mineral specimens. The rest of the group, called the “permanent party,” continued west. It had 33 people. Besides Lewis and Clark, this group consisted of 3 sergeants, 23 privates, 3 interpreters, York, and a baby, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau. Sacagawea had given birth to him in February. The party traveled in the two original canoes and six newly built canoes.

Lewis and Clark moved west into Montana. The terrain became increasingly dry, treeless, and rugged. The explorers began to see animals that were unknown to them, such as bighorn sheep and grizzly bears. The Mandan had warned them of the ferocious bears. After one encounter with a grizzly, Lewis wrote in his journal: “I must confess that I do not like the gentlemen and had reather [rather] fight two Indians than one bear.” Some grizzlies stood to a height of 8 feet (2.4 meters) and had to be shot several times to be killed. Great herds of buffalo also amazed the explorers. At times, these beasts thundered across the plains in numbers ranging from 3,000 to 10,000.

The Great Falls of the Missouri River, near Great Falls, Montana, presented the first major obstacle to the expedition. Lewis and a few men arrived at the falls on June 13, 1805. Lewis described them as “the grandest sight I ever beheld.” These falls were about 90 feet (27 meters) high. With several other falls and rapids in the region, they blocked travel by boat.

The Mandan had told Lewis and Clark that it would take the group about a half day to carry their boats and supplies around the falls and rapids. After arriving at the Great Falls, Lewis and Clark realized that the trip would take longer. Broken, rocky trails and steamy temperatures slowed the group. Savage hailstorms left them bleeding. In one region, sharp spines of prickly pear cactuses stung the explorers’ legs and feet. In addition, rattlesnakes and grizzlies constantly menaced the group. By the time the exhausted explorers returned to the river, they had hauled their boats and supplies 18 miles (29 kilometers). The effort took about a month.

As the explorers approached the mountains, they hoped to meet friendly Indigenous peoples who would provide horses and information to guide the party through the region. Luckily, in mid-August, they met a band of Shoshone. The Shoshone chief was Sacagawea’s brother or a close relative. The explorers traded for horses and supplies, and obtained a Shoshone guide. They then began their passage through the rugged Bitterroot Range of the Rocky Mountains in Montana and Idaho.

Crossing the mountains

on what is now the Lolo Trail in Idaho became perhaps the most difficult part of the journey. The trail passed through mountains that rose from 5,000 to 7,000 feet (1,500 to 2,100 meters) high. The explorers entered the trail on Sept. 11, 1805. They led their horses along rocky, narrow mountain paths. Some horses lost their footing and fell to their death. Precious supplies and equipment were lost. Winter had set in. Deepening snow covered part of the trail. The men found few wild animals to kill for food and grew increasingly hungry. To avoid starvation, they finally killed and ate some of their pack horses.

Clark and a few men in a hunting party came out of the mountains near Weippe, Idaho, on September 20. The rest of the group arrived there two days later. The party met helpful Nez Perce people and traded for food and fresh supplies. The explorers camped near the site of Lewiston, Idaho, on the Idaho-Washington border. There, the group built canoes. They used the canoes to travel down the Clearwater, Snake, and Columbia rivers. On the rivers, they faced treacherous falls and rapids. The members of the expedition became the first white people to have direct contact with the Indigenous people of this region.

Lewis and Clark learned that they were near the Pacific Ocean. On Nov. 7, 1805, Clark recorded in his journal his excitement at reaching what he thought was the Pacific coast. He wrote: “Ocian [ocean] in view! O! the joy.” The explorers later discovered that Clark had seen Gray’s Bay. The bay is actually about 20 miles (32 kilometers) from the ocean. After reaching the sea, the explorers built Fort Clatsop near Astoria, Oregon. They named the fort for the nearby Clatsop people. They all moved into their new quarters by Dec. 25, 1805.

The group spent a rainy winter at the fort. They studied the local peoples and prepared for the return trip. The new groups they met included the Chinook, Tillamook, Walla Walla, Wanapam, and Yakama.

Return to St. Louis

The homeward journey

began on March 23, 1806. In May, the expedition again reached the Nez Perce villages. Lewis describes these people as “the most hospitable, honest and sincere people that we have met with in our voyage.”

Indigenous guides had told Lewis and Clark that the route they had followed through the mountains was not the shortest. In June, Lewis and Clark divided the expedition into two groups at a spot they called Travelers’ Rest. One group, led by Lewis, would follow the shortcut, from the mountains to the Missouri River, that the guides had suggested. Clark led the other group to explore the Yellowstone River area.

Lewis’s group reached the Missouri River by the new, shorter route. They set out to explore the Marias River. Along the Marias, the party fought some Blackfeet men who tried to steal their guns and horses. The explorers escaped unharmed but killed two Blackfeet.

Clark’s group reached the Yellowstone River by a new route. At the Yellowstone, they built canoes and followed the river to its junction with the Missouri. On Aug. 12, 1806, the two groups reunited on the Missouri River below the mouth of the Yellowstone.

Nothing had been heard from the explorers for over a year. Most Americans feared they were all dead. As the group of explorers neared St. Louis, reports of their survival created great excitement. The expedition arrived at St. Louis on Sept. 23, 1806, to the welcoming cheers of the city’s people.

Results of the expedition.

The most important result of the Lewis and Clark expedition was that it enabled the United States to claim the Oregon region. This claim helped make possible the great pioneer movement that settled the West in the mid-1800’s. The explorers also established peaceful contact with most of the Indigenous groups they met. They collected a variety of Indigenous goods and gathered information on Indigenous languages and culture.

Lewis, Clark, and several other members of the expedition prepared journals of the trip. These journals describe the natural resources and Indigenous peoples of the West and contain information on many scientific matters. The journals of Lewis and Clark are the most detailed records of the expedition. They describe about 180 plants and 125 animals that had not been reported to scientists. The journals were first published in an edited version in 1814 and nearly in their entirety in 1905.

Celebrating the bicentennial

From 2003 to 2006, the states the explorers crossed, and many other states as well, marked the bicentennial of the Lewis and Clark expedition. Performers in costume reenacted historical events of the expedition. Indigenous groups who met the expedition held traditional gatherings called powwows. Colleges and universities, museums, and state and national park sites along the route offered exhibits and activities that recalled the great exploration. Many special programs took place at the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail Interpretive Center in Great Falls, Montana; the Nez Perce National Historical Park near Lewiston, Idaho; and the Fort Clatsop National Memorial (now part of the Lewis and Clark National Historical Park) near Astoria, Oregon.

See also Clark, William; Colter, John; Lewis, Meriwether; Sacagawea.