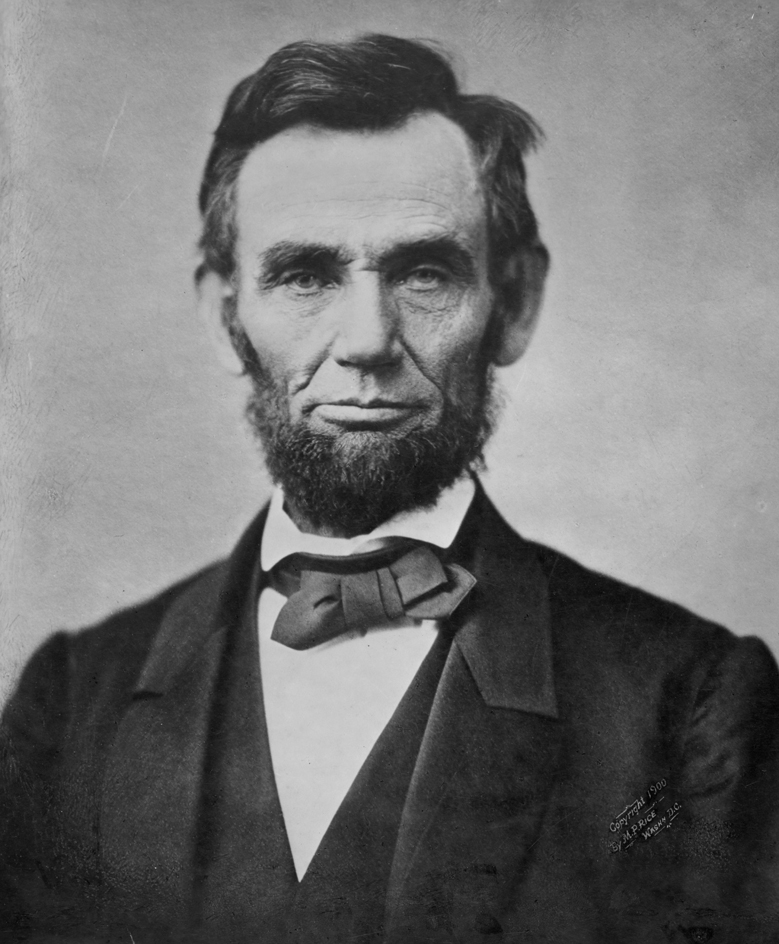

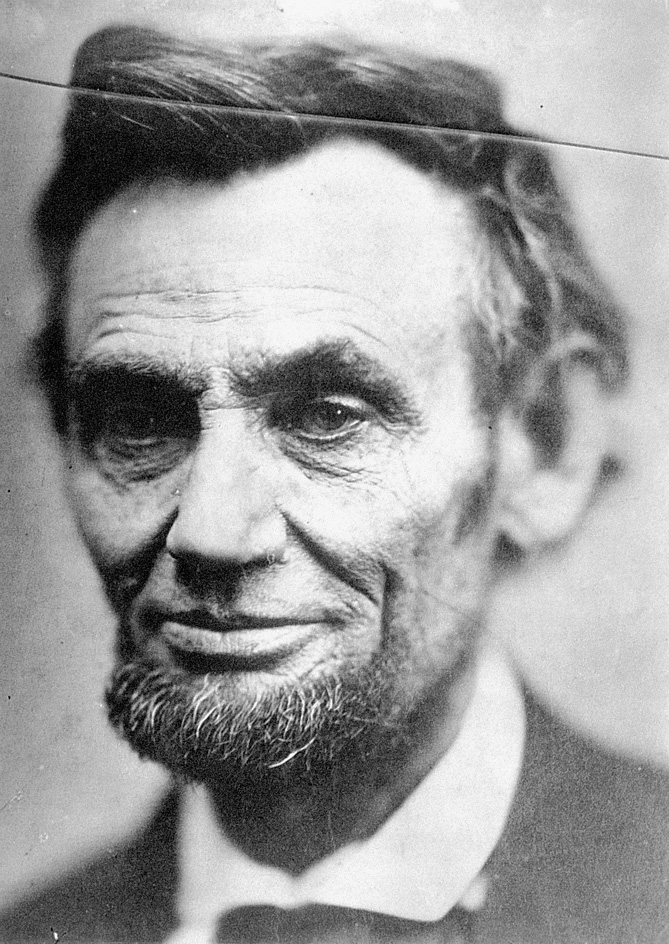

Lincoln, Abraham (1809-1865), was the 16th president of the United States. He led the nation during the American Civil War (1861-1865), which was the gravest crisis in U.S. history. Lincoln helped end slavery in the nation and helped keep the American Union from splitting apart during the war. Lincoln thus believed that he proved to the world that democracy can be a lasting form of government. Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, second inaugural address, and many of his other speeches and writings are classic statements of democratic beliefs and goals. In conducting a bitter war, Lincoln never became bitter himself. He showed a nobility of character that has worldwide appeal. Lincoln, a Republican, was the first member of his party to become president. He was assassinated near the end of the Civil War and was succeeded by Vice President Andrew Johnson. Lincoln was the first U.S. president to be assassinated.

The American people knew little about Lincoln when he became president. Little in his past experience indicated that he could successfully deal with the deep differences between Northerners and Southerners over slavery. Lincoln received less than 40 percent of the popular vote in winning the presidential election of 1860. But by 1865, he had become in the eyes of the world equal in importance to George Washington. Through the years, many people have regarded Lincoln as the greatest person in United States history.

During the Civil War, Lincoln’s first task was to win the war. He had to view nearly all other matters in relation to the war. It was “the progress of our arms,” he once said, “upon which all else depends.” But Lincoln was a peace-loving man who had earlier described military glory as “that attractive rainbow, that rises in showers of blood—that serpent’s eye that charms to destroy.” The Civil War was by far the bloodiest war in U.S. history. In the Battle of Gettysburg, for example, the more than 45,000 total casualties (people killed, wounded, captured, or missing) exceeded the number of casualties in all previous American wars put together.

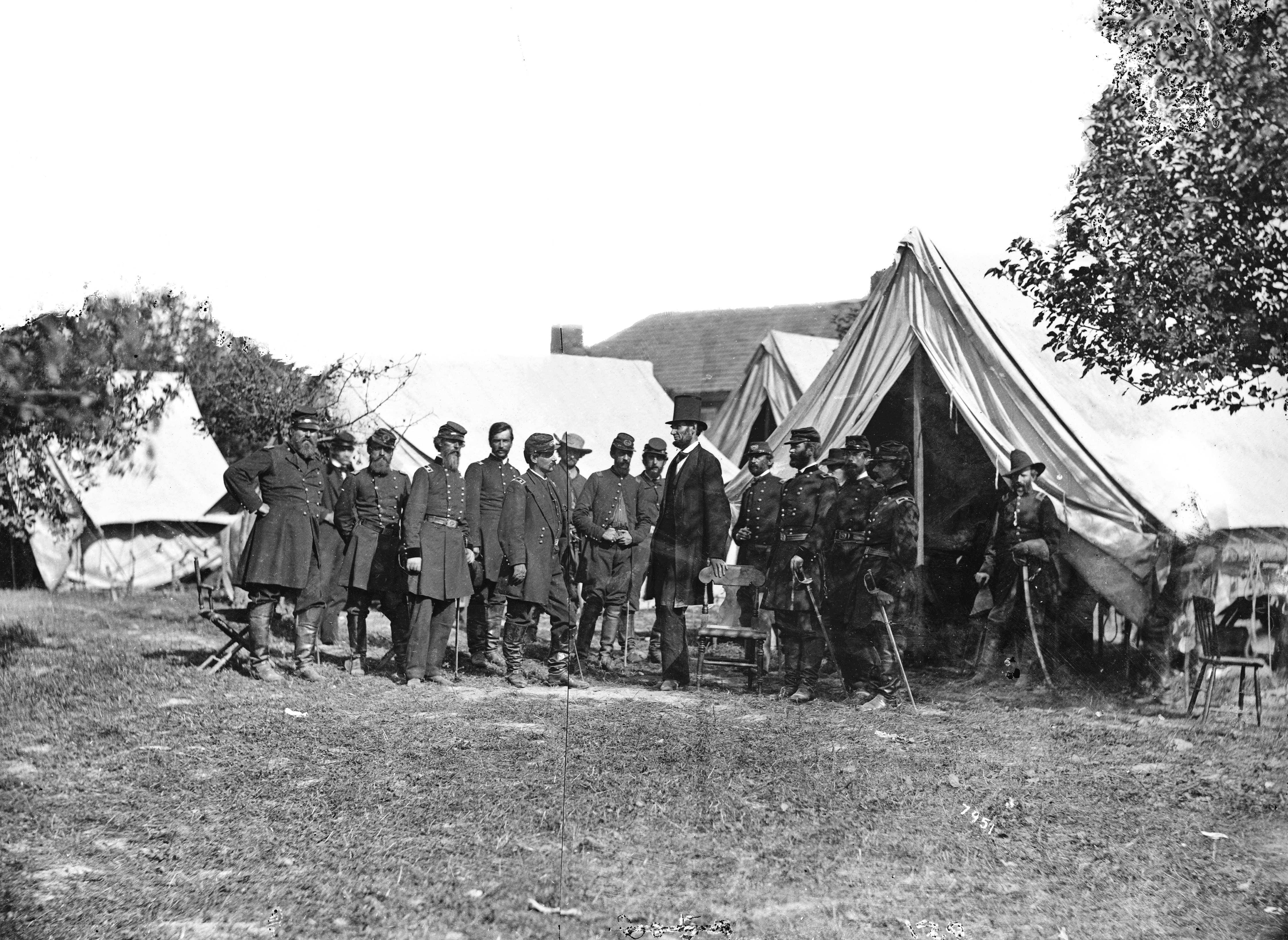

Lincoln became a remarkable war leader. Some historians believe he was the chief architect of the Union’s victorious military strategy. This strategy called for Union armies to advance against the enemy on all fronts at the same time. Lincoln also came to understand that the objective of the Union armies should be the destruction of opposing forces, not the conquest of territory. Lincoln changed generals several times because he could not find one who would fight the war aggressively. When he finally found such a general, Ulysses S. Grant, Lincoln stood firmly behind him.

Lincoln’s second great task was to keep up Northern morale through the horrible war in which many relatives in the North and South fought against one another and hundreds of thousands died. He understood that the Union’s resources vastly exceeded those of the Confederacy, and that the Union would eventually triumph if it remained dedicated to victory. For this reason, Lincoln used his great writing and speechmaking abilities to spur on his people.

If the Union had been destroyed, the United States could have become two, or possibly more, nations. These nations separately could not have become as prosperous and powerful as the United States is today. By preserving the Union, Lincoln influenced the course of world history. By ending slavery, he helped assure the moral strength of the United States. His own life story, too, has been important. He rose from humble origin to the nation’s highest office. Millions of people regard Lincoln’s career as proof that democracy offers all people the best hope of a full and free life.

Life in the United States during Lincoln’s administration revolved around the war. But almost miraculously, the nation also laid out a blueprint for modern America during the war years. Economic development played an important role in Lincoln’s vision of America’s future, in which all people would have the right to rise in life. National banking legislation provided for paper money as we know it today—and for federal controls to assure sound banking and credit. United States tariffs on European manufactured goods helped limit foreign competition and encouraged the growth of American industry. The administration encouraged labor unions. The government’s homestead laws gave free land to settlers. Immigration was encouraged, as was the settlement of the West. Land was also granted for colleges that later became great state universities and for the construction of the nation’s first transcontinental railroad. In addition, the nation’s first income tax was levied to provide funds for the war.

Abraham Lincoln

Soldiers and civilians alike sang “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” or “Dixie.” Winslow Homer’s painting Prisoners from the Front brought him his first fame. Patriotic literature of the time included John Greenleaf Whittier’s poem “Barbara Frietchie” and Edward Everett Hale’s story “The Man Without a Country.” Lincoln and numerous other Americans chuckled at the humorous writings of Artemus Ward and admired the patriotic prints of Currier and Ives and other artists.

Early life

Family background.

Soon after Lincoln was nominated for the presidency, he wrote a brief autobiography. It began: “Abraham Lincoln was born Feb. 12, 1809, then in Hardin, now in the more recently formed county of Larue, Kentucky. His father, Thomas, & grandfather Abraham, were born in Rockingham county Virginia, whither their ancestors had come from Berks county Pennsylvania. His lineage has been traced no farther back than this.”

Since Lincoln’s time, his ancestry has been traced to a weaver named Samuel Lincoln who emigrated from Hingham, England, to Hingham, Massachusetts in 1637. Samuel Lincoln founded the Lincoln family in America. The families of several of his children played important parts in Massachusetts history.

Descendants of Mordecai Lincoln, a son of Samuel, moved to New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. One was a great-great-grandson named Abraham. This Abraham Lincoln was the grandfather of the future president. He owned a farm in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia during the American Revolution (1775-1783). In 1782, he and his wife and five small children traveled to the wilderness of Kentucky. An Indigenous (native) raider killed him on his farm there in 1786.

One of his sons, Thomas Lincoln, became the father of the future president. In later years, the president said his father was “a wandering laboring boy, and grew up literally without education.” Thomas Lincoln worked as a frontier farm hand during most of his youth. But he learned enough skill at woodworking to earn extra money as a carpenter. In 1806, when he was 28 years old, he married Nancy Hanks. Nancy came from what her son described as an “undistinguished” Virginia family of humble, ordinary people. Historians know only that she was the daughter of a Lucy Hanks.

Thomas and Nancy Lincoln lived in Elizabethtown, Kentucky, for the first 18 months of their marriage. Their first child, Sarah, was born there in 1807. The next year, Thomas Lincoln bought a farm on the South Fork of the Nolin River, about 5 miles (8 kilometers) south of Elizabethtown. Abraham Lincoln was born on this farm.

Boyhood.

The Lincolns lived for two years on the farm where Abraham was born. Then they moved to a farm on Knob Creek, 10 miles (16 kilometers) away. When Sarah and Abraham could be spared from their chores, they went to a log schoolhouse. There the children learned reading, writing, and arithmetic.

Many people believe that because Lincoln began his life in a log cabin, he was born in poverty. Although it is true that the Lincolns were poor, many people at that time lived in log cabins. The Lincolns were as comfortable as most of their neighbors, and Abraham and Sarah were well fed and well clothed for the times. A third child, Thomas, died in infancy.

Thomas Lincoln had trouble over property rights throughout his years in Kentucky. In 1816, he decided to move to Indiana, where people could buy land directly from the government. Besides, Thomas Lincoln did not believe in slavery, and Indiana had no slavery.

The Lincolns loaded their possessions into a wagon. They traveled northward to the Ohio River and were ferried across. Then they traveled through the thick forests to Spencer County, in southwestern Indiana. There, Thomas Lincoln began the task of changing 160 acres (65 hectares) of forestland into a farm.

The Lincolns found life harder in Indiana than in Kentucky. They arrived early in winter and needed shelter at once. Thomas and his son built a temporary three-sided structure made of logs, called a “half-faced camp.” A fire on the fourth side burned night and day. Soon after finishing this shelter, the boy and his father began to build a log cabin. The family moved into it in February 1817.

Bears and other wild animals roamed the forests of this remote region. Trees had to be cut and fields cleared so that a crop could be planted. Although Abraham was only 8, he was large for his age and had enough strength to swing an ax. For as long as he lived in Indiana, he was seldom without his ax. He later called it “that most useful instrument.”

Slowly, life became happier on the farm. But in October 1818, Nancy Lincoln died of what the pioneers called “milk sickness.” This illness was caused by poison in the milk of cows that had eaten snakeroot. Thomas buried his wife among the trees on a hill near the cabin.

Life on the farm became dull and cheerless after the death of Nancy Lincoln. Sarah, now 12, kept house as well as she could for more than a year. Then Thomas Lincoln returned to Kentucky for a visit. While there, on Dec. 2, 1819, he married Sarah Bush Johnston, a widow. He had known her before her first marriage. The new Mrs. Lincoln brought her three children, aged 12, 8, and 5, back to Indiana. Her arrival at the cabin in Indiana ended the long months of loneliness. Mrs. Lincoln and young Abe became, and remained, extremely close.

Education.

Abraham Lincoln grew from a boy of 7 to a man of 21 on the wild Indiana frontier. His education can best be described in his own words:

“There were some schools, so called; but no qualification was ever required of a teacher, beyond “readin, writin, and cipherin,’ to the Rule of Three. If a straggler supposed to understand latin, happened to sojourn in the neighborhood, he was looked upon as a wizzard. There was absolutely nothing to excite ambition for education. Of course when I came of age I did not know much. Still somehow, I could read, write, and cipher to the Rule of Three; but that was all.”

Lincoln’s formal schooling totaled less than a year. Books and paper were scarce on the frontier. Like other boys and girls of his time, Lincoln made his own arithmetic textbook. Several of its pages still exist. Abraham often worked his arithmetic problems on boards, then shaved the boards clean with a drawknife, and used them again and again. He would walk a great distance for a book. The few he could borrow were good ones. They included Robinson Crusoe, Pilgrim’s Progress, and Aesop’s fables. Lincoln also borrowed a history of the United States and a schoolbook or two.

In 1823, when Abraham was 14, his parents joined the Pigeon Creek Baptist Church. There was bitter rivalry among Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, and other denominations. This may help explain why Lincoln never joined any church, and why he never attended church regularly. Yet he became a man of deep religious feelings. He came to know the Bible thoroughly. Biblical references and quotations enriched his later writings and speeches. As president, he often turned to Scripture for comfort and guidance.

Another book also impressed young Lincoln deeply— a biography of the nation’s first president. He borrowed the book from a neighbor and had nearly finished it when it was damaged by rainwater. He then worked hard on his neighbor’s farm to pay the cost of the book—and to keep it. He told about it years later in a speech before the New Jersey Senate:

“May I be pardoned if, on this occasion, I mention that away back in my childhood, the earliest days of my being able to read, I got hold of a small book, such a one as few of the younger members have ever seen, Weems’s Life of Washington. I remember all the accounts there given of the battle fields and struggles for the liberties of the country … and you all know, for you have all been boys, how these early impressions last longer than any others. I recollect thinking then, boy even though I was, that there must have been something more than common that those men struggled for.”

Youth on the frontier.

Abraham reached his full height of 6 feet 4 inches (193 centimeters) long before he was 20. He was thin and awkward, big-boned and strong. The young man developed great strength in his chest and legs, and especially in his arms. He had a homely face and dark skin. His hair was black and coarse, and stood on end.

Even as a boy, Lincoln showed ability as a speaker. He often amused himself and others by imitating some preacher or politician who had spoken in the area. People liked to gather at the general store in the crossroads village of Gentryville. Lincoln’s gift for telling stories made him a favorite with the people there, though his own father often struck him when he showed off his mimicking skills in public. In spite of his youth, he was well known in his neighborhood.

A boy of Lincoln’s size and strength had no trouble finding hard work. People always needed great piles of cut wood for cooking and for warmth. Lincoln could split logs for fence rails. He could plow fields, cut and husk corn, and thresh wheat with a flail. Lincoln worked for a neighbor when his father could spare him.

The Ohio River, 15 miles (24 kilometers) away, attracted Lincoln strongly. The first money he earned was for rowing passengers to a steamboat in midstream. In 1828, he helped take a flatboat loaded with farm produce to New Orleans. The trip gave him his first view of the world beyond his own community. That same year, his sister died in childbirth.

In 1830, Thomas Lincoln decided to move again. The years in Indiana had not been successful. The dreaded milk sickness was again striking down settlers. Relatives in Illinois sent word of deep, rich, black soil on its treeless prairies. The Lincolns and several other families started west. They reached their destination two weeks later, and settled 10 miles (16 kilometers) west of Decatur, on the north bank of the Sangamon River.

Lincoln was now 21 and free to strike out for himself. But he remained with his father one more year. He helped plant the first crop, and split rails for a cabin and fences. He worked for neighboring settlers during the winter. In the spring of 1831, a trader named Denton Offutt hired Lincoln and two other young men to take a flatboat to New Orleans. This trip gave Offutt a good impression of his lanky boat hand. He hired Lincoln as a clerk in his new store in the tiny village of New Salem, Illinois, 20 miles (32 kilometers) northwest of Springfield. While Lincoln was away, his parents moved to Coles County, where they lived for the rest of their lives.

New Salem years

Life on his own

began for Lincoln when he settled in New Salem. He lived there almost six years, from July 1831 until the spring of 1837. The village consisted of log cabins clustered around a mill, a barrelmaker’s shop, a wool-carding machine, and a few general stores.

The villagers helped Lincoln in many ways. The older women mended his clothes and often gave him meals. Jack Kelso, the village philosopher, introduced him to the writings of the English dramatist William Shakespeare and the Scottish poet Robert Burns. These works, and the Bible, became Lincoln’s favorite reading.

Lincoln arrived in New Salem, as he said, “a piece of floating driftwood.” He earned little and slept in a room at the rear of Offutt’s store. Within a few months, the business failed. Lincoln would have been out of a job if the Black Hawk War had not begun in 1832.

The Black Hawk War.

By late 1831, the federal government had moved most of the Indigenous Sauk and Fox people from Illinois to Iowa. In the spring of 1832, the Sauk leader Black Hawk led a band of about 1,000 Indigenous people back across the Mississippi River to try to regain their lands near Rock Island (see Black Hawk). The governor called out the militia, and Lincoln volunteered for service.

Lincoln’s company consisted of men from the New Salem area. The men promptly elected him captain. This was only nine months after he had settled in the village. Even after he had been nominated for president years later, Lincoln said this honor “gave me more pleasure than any I have had since.” It provided the first significant indication of his gift for leadership. Lincoln’s comrades liked his friendliness, his honesty, and his skill at storytelling. They also admired his great strength and his sportsmanship in wrestling matches and other contests.

Lincoln’s term of service ended after 30 days, but he reenlisted, this time as a private. A month later, he enlisted again. He served a total of 90 days but saw no fighting. He later described his militia experiences as “bloody struggles with the musquetoes” and “charges upon the wild onions.”

Search for a career.

Before his military service, many of Lincoln’s friends had encouraged him to become a candidate for the state legislature. Spurred by their faith, he announced his candidacy in March 1832. The Black Hawk War prevented him from making much of a campaign. He arrived home in July, only two weeks before the election. Lincoln was defeated in the election, but the people in his own precinct gave him 277 of their 300 votes.

Lincoln faced the problem of making a living. He thought of studying law but decided he could not succeed without a better education. Just then, he had a chance to buy a New Salem store on credit, in partnership with William F. Berry. Lincoln later recalled that the partnership “did nothing but get deeper and deeper in debt.” The store failed after a few months.

In May 1833, Lincoln was appointed postmaster of New Salem. Soon afterward, the county surveyor offered to make him a deputy. Lincoln knew nothing about surveying, but he prepared for the work by hard study. Odd jobs and fees from his two public offices earned him a living.

Berry died in 1835, leaving Lincoln liable for the debts of the partnership, about $1,100. It took Lincoln several years to pay what he jokingly called his “national debt,” but he finally did it. His integrity helped him earn the nickname “Honest Abe.”

In New Salem, Lincoln grew close to a girl named Ann Rutledge. After she died in the summer of 1835, he grieved deeply. Scholars have debated their relationship for years. Although Ann was engaged to another man, it seems likely that the she and Lincoln did fall in love. But within 18 months, Lincoln recovered from his loss and proposed marriage to a Kentucky girl, Mary Owens. He met her while she was visiting her sister in New Salem. Their affection for each other was not especially deep, however, and Owens rejected him.

Success in politics.

In 1834, Lincoln again ran for the legislature. He had become better known by this time, and he won election as a Whig (see Whig Party). He served four successive two-year terms in the lower house of the Illinois General Assembly. During his first term, he met a rising young Democratic legislator, Stephen A. Douglas.

Lincoln quickly came to the front in the legislature. He was witty and ready in debate. His skill in party management enabled him to become the Whig floor leader at the beginning of his second term. He took leading parts in the establishment of the Bank of Illinois and in the adoption of a plan for a system of railroads and canals. This plan broke down after the Panic of 1837. Lincoln also led a successful campaign for moving the state capital from Vandalia to Springfield.

While in the legislature, Lincoln made his first public statement on slavery. In 1837, the legislature passed, by an overwhelming majority, resolutions condemning abolition societies (societies that urged freedom for enslaved Black people). Lincoln and another legislator, Dan Stone, filed a protest. Their protest arose from the legislature’s failure to call slavery an evil practice. Lincoln and Stone declared that “the institution of slavery is founded on both injustice and bad policy.” Still, Lincoln and Stone admitted that Congress had no power to interfere with slavery in the states where it existed. They believed “the promulgation of abolition doctrines tend rather to increase than abate its evils.” Slavery had become a much greater issue 23 years later, when Lincoln was nominated for president. He said then that his protest in the Illinois legislature still expressed his position on slavery.

Lincoln the lawyer

Study.

In 1834, during Lincoln’s second campaign for the legislature, John T. Stuart had urged him to study law. Stuart was an attorney in Springfield and a leading member of the legislature. Lincoln overcame his doubts about his education. He borrowed law books from Stuart and studied them. He sometimes walked 20 miles (32 kilometers) from New Salem to Springfield for books. Henry E. Dummer, Stuart’s law partner, recalled:

“Sometimes he walked, but generally rode. He was the most uncouth looking young man I ever saw. He seemed to have but little to say; seemed to feel timid, with a tinge of sadness visible in the countenance, but when he did talk all this disappeared for the time and he demonstrated that he was both strong and acute. He surprised us more and more at every visit.”

On Sept. 9, 1836, Lincoln received his license to practice law, although his name was not entered on the roll of attorneys until March 1, 1837. The population of New Salem had dropped by that time, and Lincoln decided to move to the new state capital. Carrying all he owned in his saddlebags, he rode into Springfield on April 15, 1837. There he became the junior partner in the law firm of Stuart and Lincoln.

In Lincoln’s time, there were few law schools. Most lawyers simply “read law” in the office of an attorney. Years later, in giving advice to a law student, Lincoln explained his method of study:

“If you are resolutely determined to make a lawyer of yourself, the thing is more than half done already. It is but a small matter whether you read with anybody or not. I did not read with anyone. Get the books, and read and study them till you understand them in their principal features; and that is the main thing. It is of no consequence to be in a large town while you are reading. I read at New Salem, which never had three hundred people living in it. The books, and your capacity for understanding them, are just the same in all places … . Always bear in mind that your own resolution to succeed, is more important than any other one thing.”

Early practice.

Lincoln’s partnership with Stuart lasted until the spring of 1841. Then he became the junior partner of Stephen T. Logan, one of the greatest lawyers who ever practiced in Illinois. This partnership ended in the fall of 1844.

Lincoln then asked William H. Herndon to become his partner. Herndon, nine years younger than Lincoln, had just received his license to practice law. Lincoln called him “Billy,” but Herndon always called his partner “Mr. Lincoln.” The two men never formally dissolved their law firm. More than 16 years later, Lincoln visited his old office on his last day in Springfield before leaving for Washington to be inaugurated as president. He noticed the firm’s signboard at the foot of the steps and said: “Let it hang there undisturbed. Give our clients to understand that the election of a president makes no change in the firm of Lincoln and Herndon.”

The practice of law in Illinois was not specialized in Lincoln’s time. It included injury claims, divorces, murders and assaults, and even runaway slave cases. Lincoln tried his first case in the circuit court of Sangamon County. He practiced in the Illinois federal courts within two years after his admission to the bar. A year later, he tried the first of many cases in the state supreme court. But all the while, he also handled cases before justices of the peace. He also gave advice and opinions on many matters for small fees.

Lincoln’s family.

Soon after Lincoln moved to Springfield, he met Mary Todd (Dec. 13, 1818 – July 16, 1882), an attractive young woman from Kentucky who lived there with a married sister. They had a stormy courtship and at one time broke their engagement. They married on Nov. 4, 1842, when Lincoln was 33 and Todd was 23.

Mary Todd Lincoln was high-strung and socially ambitious. Lincoln tended to be moody and absent-minded. Their contrasting personalities sometimes caused friction. But they had a loving marriage that lasted until Abraham’s death. See Lincoln, Mary Todd.

Lincoln and his bride first lived in a Springfield boarding house, where they paid $4 a week. Eighteen months after the marriage, Lincoln bought a plain but comfortable frame house, later expanded, in which the family lived until he became president. By the time he bought the house, his first son, Robert Todd, was 9 months old (see Lincoln, Robert Todd). The Lincolns’ second son, Edward Baker, was born in 1846, but died four years later. William Wallace, born in 1850, died in the White House at the age of 11. Their fourth son, Thomas, usually called Tad, became ill and died in 1871 at age 18.

The family lived comfortably. Lincoln became a highly successful lawyer and politician. He was not the poverty-stricken failure sometimes portrayed in legend. Lincoln often cared for his own horse and milked the family cow, but so did most of his neighbors. The Lincoln family usually employed a servant to help with the housework.

Riding the circuit.

The state of Illinois was, and still is, divided into circuits for judicial purposes. Each circuit consisted of several counties where court was held in turn. The judge and many lawyers traveled from county to county. They tried such cases as came their way during each term.

Lincoln “traveled the circuit” for six months each year. He loved this kind of life. The small inns where the lawyers stayed had few comforts, but they offered many opportunities for meeting people. Lively talk and storytelling appealed to Lincoln. He also liked the long rides across the prairies. Lincoln’s circuit at its largest included 15 counties and covered about 8,000 square miles (21,000 square kilometers).

Lincoln developed traits as a lawyer that made him well known throughout Illinois. He could argue a case strongly. He sometimes persuaded clients to settle their differences out of court, which meant a smaller fee, or no fee at all, for him. In court, Lincoln could present a case so that 12 jurors, often poorly educated, could not fail to understand it. He could also argue a complicated case before a well-informed judge. He prepared his cases thoroughly and was unfailingly honest.

National politics

Search for advancement.

After four terms in the Illinois legislature, Lincoln wanted an office with greater prestige. He had served the Whig Party well, and election to Congress became his goal.

In 1840, Lincoln made a speaking tour of the state for William Henry Harrison, the Whig candidate for president. He campaigned on the issue of a sound central banking system, speaking out in favor of rechartering the Bank of the United States. Lincoln believed his service had earned him the nomination for Congress from his district. In 1843, and again in 1844, the nomination went to other candidates.

Disappointed, but not bitter, Lincoln worked for the election of Henry Clay, the Whig presidential candidate in 1844. During this campaign, Lincoln focused on the need for a tariff that would raise the cost of imports and aid American industrial growth. Two years later, Lincoln received his reward and won the Whig nomination for the U.S. House of Representatives. His opponent in the election was Peter Cartwright, a well-known Methodist circuit rider. The Whigs firmly controlled Lincoln’s district, and he got 6,340 of the 11,418 votes cast.

Congressman.

Lincoln took his seat in Congress on Dec. 6, 1847. By that time, the United States had won the Mexican War, although a peace treaty between Mexico and the United States had not yet been signed. Lincoln joined his fellow Whigs in blaming President James K. Polk for the war. He said of Polk, “The blood of this war, like the blood of Abel, is crying to heaven against him.” He warned that “military glory” was an “attractive rainbow” that could result in “showers of blood.” Still, Lincoln would not abandon U.S. troops on the battlefield and voted to supply them with equipment.

Lincoln failed to make much of a reputation during his single term in Congress. He gave notice that he intended to introduce a bill to free the enslaved people in the District of Columbia, but he never did. He emphasized his position on slavery by supporting the Wilmot Proviso, which would have banned slavery in any territory acquired from Mexico (see Wilmot Proviso).

Throughout his term, Lincoln supported the Whig policy of having the federal government pay for internal improvements. He made several speeches in support of this policy, and once reproved President Polk for vetoing funds to make rivers and harbors more navigable and thus increase commerce. Lincoln worked for the nomination and election of Zachary Taylor, the Whig candidate for president in 1848.

Return to law.

Lincoln’s term ended on March 4, 1849. He could have run for reelection, but he had agreed in advance to rotate the Whig nomination to another candidate. Lincoln tried unsuccessfully to get an appointment from the new president as commissioner of the General Land Office. The administration offered to appoint him secretary, then governor, of Oregon Territory. Lincoln refused both offers.

Lincoln returned to Springfield. He practiced law more earnestly than ever before. He continued to travel the circuit, but he appeared more often in the higher courts. He also handled more important cases. Corporations and big businesses were becoming increasingly important in Illinois and neighboring states. Lincoln represented them frequently in lawsuits, and soon prospered. The largest fee he ever received, $5,000, was for his successful defense of the Illinois Central Railroad in an important tax case. After 1849, Lincoln’s reputation grew steadily. In the 1850’s, he was known as one of the leading lawyers of Illinois.

Reentry into politics.

Lincoln revered the Founding Fathers. He believed they had written a promise of freedom and equality into the Declaration of Independence. He once said: “I have never had a feeling politically which did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence.” During his early years in politics, Lincoln had looked up to Henry Clay as an ideal politician. But he looked to Thomas Jefferson for his democratic political principles and to Alexander Hamilton for his economic principles.

In 1854, a sudden change in national policy on slavery brought Lincoln back into the center of political activity in Illinois. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 had prohibited slavery in new territories north of an east-west line that was an extension of Missouri’s southern boundary (see Missouri Compromise). Early in 1854, however, Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois introduced a bill to organize the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. The bill provided that the settlers of all new territories should decide for themselves whether they wanted slavery. As approved by Congress, the Kansas-Nebraska Act repealed the Missouri Compromise. See Kansas-Nebraska Act.

Lincoln and many others had believed that slavery had been permanently limited and would in time die out. Lincoln believed that the new policy gave new life to slavery, and it outraged him.

Lincoln always opposed slavery, but he never became an outright, or complete, abolitionist. He believed that the bonds holding the nation together would be strained if Americans made a rapid break with the past. He also knew that abolitionists could never aim for national office. Lincoln granted that slavery had the legal protection that the Constitution gave it. But he wanted people to realize that slavery was evil and that it should be put on what he called “the road to ultimate extinction.”

Douglas refused to admit that slavery was wrong. He said he did not care whether the people of new territories voted for or against slavery. Lincoln, in contrast, believed that the nation stood for freedom and equality. He felt it must not be indifferent to the unjust treatment of any person. To ignore moral values, he said, “deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world.” It enabled the enemies of free institutions “to taunt us as hypocrites.” Lincoln resolved to do what he could to reverse the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

A turning point

in Lincoln’s life came with the rise of the slavery controversy. Fighting against what he termed the “cancer” of bondage, he rose to the presidency and directed a bloody civil war that would put an end to what he saw as an evil institution. But first, many political battles had to be fought.

Lincoln entered the congressional election campaign of 1854 to help a candidate who opposed the Kansas-Nebraska Act. But when Senator Douglas returned to Illinois to justify the new law, Lincoln opposed him wherever he could. At Springfield, Peoria, and Chicago, Lincoln delivered such powerful speeches that he became known as the leader of the Illinois forces opposing the Kansas-Nebraska Act. He was again elected to the Illinois legislature, but he resigned to run for the United States Senate.

At that time, the legislature elected senators. On the first ballot, Lincoln received 45 votes, which was 5 short of a majority. On each succeeding ballot, his vote dwindled. Finally, to keep a Douglas supporter from being elected, Lincoln persuaded his followers to vote for Lyman Trumbull, who had started with only 5 votes. Trumbull was elected.

The Whig Party began falling apart during the 1850’s, largely because party members in various parts of the country could not agree on a solution to the slavery problem. In 1856, Lincoln joined the antislavery Republican Party, then only two years old. During the presidential election campaign that year, he made more than a hundred speeches in behalf of John C. Frémont, the Republican candidate. Frémont lost the election to Democrat James Buchanan. But Lincoln had strengthened his own position in the party through his unselfish work.

The debates with Douglas.

In 1858, the Republicans named Lincoln their “first and only choice” to run against Douglas for the U.S. Senate. Lincoln accepted the honor with a speech that aroused much controversy. Many people thought his remarks stirred up conflict between the North and South. Lincoln said:

“A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved—I do not expect the house to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other. Either the opponents of slavery will arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction; or its advocates will push it forward till it shall become alike lawful in all the States—old as well as new, North as well as South.”

After a few speeches, Lincoln challenged Douglas to a series of debates. Douglas accepted and named seven towns for the meetings. The first debate was held at Ottawa, Illinois, on Aug. 21, 1858. The last was at Alton, Illinois, on October 15. Each candidate spoke outdoors for an hour and a half. Large crowds attended each debate except the one at Jonesboro, in the southernmost part of the state. Newspapers from around the country reported and reprinted the debates, and the two men drew national attention.

The debates centered on the extension of slavery into free territory. Douglas defended the policy of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. He called this policy popular sovereignty. His opponents ridiculed it as squatter sovereignty and warned that it would make slavery national and permanent (see Popular sovereignty). Lincoln argued that the Supreme Court of the United States, in the Dred Scott Decision, had opened the way for slavery to enter all the territories (see Dred Scott Decision). In the debate held at Freeport, Illinois, Douglas denied this argument. He contended that the people of any territory could keep slavery out of that territory simply by refusing to pass local laws protecting it. This position became known as the Freeport Doctrine. Lincoln insisted that there was a fundamental difference between Douglas and himself. Douglas ignored the moral question of slavery, but Lincoln regarded slavery “as a moral, social, and political evil.” Douglas, in turn, tried to depict Lincoln as a dangerous radical who favored racial equality.

In addition to the debates, both men spoke almost daily to rallies of their own. Each traveled throughout the state. Before the exhausting campaign ended, Douglas’s deep bass voice had become so husky that it was hard to understand him. Lincoln’s high, penetrating voice still reached the limits of a large audience.

In the election, Lincoln candidates for the legislature received more votes than their opponents. But the state was divided into districts in such a way that Douglas candidates won a majority of the seats. As a result, Douglas was reelected by a vote of 54 to 46.

The debates made Lincoln a national figure. Early in 1860, he delivered a triumphant address at Cooper Union in New York City. The speech ended with the famous plea: “Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith let us to the end dare to do our duty as we understand it.” This address, together with others delivered later in New England, made a strong impression on many influential eastern Republicans.

Election of 1860.

The Republican National Convention met in Chicago on May 16, 1860. Lincoln was by no means unknown to the delegates. The week before, at the Illinois state Republican convention, his supporters had nicknamed him “the Railsplitter.” This nickname, recalling the days when Lincoln had split rails for fences, helped make him even better known to the delegates. But other party leaders had larger followings. Senator William H. Seward of New York had the strongest support, but he also had many enemies. Senator Salmon P. Chase of Ohio lacked the united support of even his own state. Lincoln had never held a prominent national office, and he had no bitter enemies. He held moderate views on the slavery question. His humble background could be counted on to arouse great enthusiasm among the voters.

On the first ballot, Seward received 1731/2 votes, Lincoln 102, and Chase 49. Lincoln gained the support of Pennsylvania and Indiana on the second ballot, and he received 181 votes to 1841/2 for Seward. During the third ballot, Lincoln continued to gain strength. Before the result was announced, Ohio switched four votes from Chase to Lincoln. This gave Lincoln more than the 233 votes needed to win the Republican nomination. The delegates nominated Senator Hannibal Hamlin of Maine for vice president.

Like most other presidential candidates of his period, Lincoln felt it was undignified to campaign actively. He therefore stayed quietly in Springfield during the election campaign. His followers, however, more than made up for his inactivity.

Lincoln benefited from a split in the opposing Democratic Party, as Senator Douglas, the nation’s leading Democrat, had angered the proslavery wing of his party. Northern Democrats nominated him for president, but the Southern faction of the Democratic Party chose Vice President John C. Breckinridge. A fourth party, calling itself the Constitutional Union Party, nominated former Senator John Bell of Tennessee.

With the opposition split, Lincoln won election easily, receiving 180 electoral votes to 72 for Breckinridge, 39 for Bell, and 12 for Douglas. But more Americans voted against Lincoln than for him. The people gave him 1,865,908 votes, compared to a combined total of 2,819,122 for his opponents. All Lincoln’s electoral votes, and nearly all his popular votes, came from the North. Never before had a president been elected by one region alone.

Lincoln’s administration (1861-1865)

The South secedes.

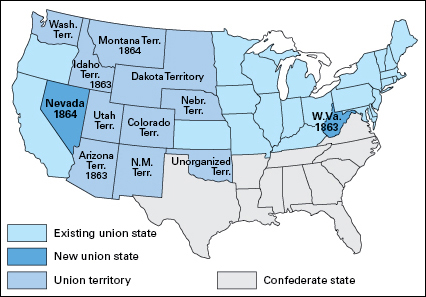

During the months before Lincoln’s election, many Southern leaders threatened to withdraw their states from the Union if Lincoln should win. On Dec. 20, 1860, South Carolina passed an Ordinance of Secession that declared the Union dissolved as far as that state was concerned. By the time Lincoln became president, six other Southern States had withdrawn from the Union. Four more states followed later. The seceded states organized themselves into the Confederate States of America. See Confederate States of America.

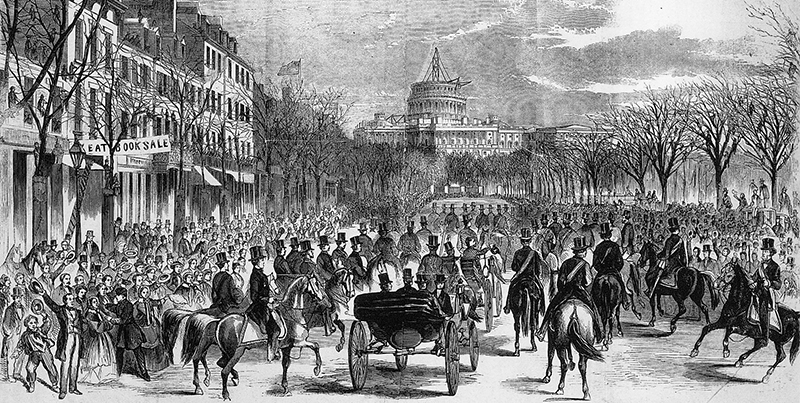

First inauguration.

Lincoln said farewell to his Springfield neighbors on Feb. 11, 1861. He parted with these words: “Here I have lived a quarter of a century, and have passed from a young to an old man. Here my children have been born, and one is buried. I now leave, not knowing when, or whether ever, I may return, with a task before me greater than that which rested upon Washington. Without the assistance of that Divine Being who ever attended him, I cannot succeed. With that assistance I cannot fail. Trusting in Him, who can go with me, and remain with you and be everywhere for good, let us confidently hope that all will yet be well. To His care commending you, as I hope in your prayers you will commend me, I bid you an affectionate farewell.”

The long train trip to Washington, D.C., had been carefully planned to include stops at most large Eastern cities. This allowed many thousands of people to see the man who would be their next president. Lincoln had grown a beard that gave him a more dignified appearance. While in Philadelphia, Lincoln heard a report of an assassination plot in Baltimore, the only Southern stop along his route. His advisers persuaded him to cut short his trip. Lincoln continued in secret to Washington, arriving early on the morning of February 23.

On March 4, 1861, Lincoln took the oath of office and became the 16th president of the United States. In his inaugural address, Lincoln denied that he had any intention of interfering with slavery in states where the Constitution protected it. He urged the preservation of the Union. Lincoln warned that he would use the full power of the nation to “hold, occupy, and possess” the “property and places” belonging to the federal government. By “property and places,” he meant forts, arsenals, and custom houses. Lincoln’s closing passage had great beauty and literary power. He appealed to “the mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land.”

Although several of his choices had been leaked in advance, Lincoln formally announced his Cabinet the day after his inauguration. Four members, William H. Seward, Salmon P. Chase, Simon Cameron, and Edward Bates, had been his rivals for the presidential nomination. The Cabinet members represented many shades of opinion within the Republican Party and included a Democrat for balance. On the whole, they were an exceptionally able group.

Fort Sumter and war.

As the Southern States seceded, they seized most of the federal forts within their boundaries. Lincoln had to decide whether the remaining forts should be strengthened and whether to try to retake the forts already in Southern hands.

Fort Sumter, in Charleston Harbor, became a symbol of an indivisible Union. Major Robert Anderson commanded the Union garrison there. If Lincoln withdrew the troops, a storm of protest would rise in the North. If he reinforced Fort Sumter, the South would consider it an act of war.

As a compromise, Lincoln decided to send only provisions to Anderson, whose supplies were running low. He informed South Carolina of his intention. Leaders of the state regarded the relief expedition as a hostile act, and they demanded Anderson’s surrender. Anderson refused, and on April 12, General Pierre G. T. Beauregard ordered Confederate artillery to fire on the fort. Anderson surrendered the next day. The attack on Fort Sumter marked the start of the Civil War. See Civil War, American.

Lincoln met the crisis with energetic action. He called out the militia to suppress the “insurrection.” He proclaimed a blockade of Southern ports and expanded the Army beyond the limit set by law. However, Southern sympathizers living in the North objected to and obstructed the war effort. In response, Lincoln suspended the privilege of habeas corpus in areas where these Southern sympathizers were active (see Habeas corpus). This action meant that antiwar Northerners could be arrested and held without formal charges. In addition, Lincoln ordered the spending of federal funds without waiting for congressional appropriations.

Chief Justice Roger B. Taney attacked Lincoln for suspending habeas corpus. But Lincoln believed the action to be within the war powers granted to the president by the Constitution. He justified his acts when Congress met for the first time in his administration on July 4, 1861. The message Lincoln delivered to this special session of Congress ranks as one of his greatest state papers. In his message, Lincoln posed a question that even today is difficult to answer: “Are all the laws but one to go unexecuted, and the government itself go to pieces lest that one be violated?” Lincoln called the historic choice a “people’s contest.”

Lincoln felt that the breakup of the American nation would be a tragedy. Not only Americans, but ultimately all people, would suffer. To him, the United States represented an experiment in the people’s ability to govern themselves. If it failed, monarchs, dictators, and their supporters could say that people were not capable of ruling themselves, and that someone must rule them. Lincoln regarded the fate of world democracy as the central issue of the Civil War.

Building the army.

Two days after Fort Sumter fell, Lincoln called for 75,000 men for the Army. The North offered far more volunteers than the government could equip. By July 1861, an army had been assembled near Washington. An equal force of Confederates had taken position across the Potomac River in Virginia. Richmond, Virginia, was the Confederate capital.

Many Northerners clamored for action. They believed Union forces could end the war by defeating the Confederates in one battle. Newspaper headlines blazed with the cry “On to Richmond!” The administration yielded to these pressures. Lincoln ordered the Northern army forward under General Irvin McDowell. The result was the first Battle of Bull Run (known in the South as the first Battle of Manassas) on July 21, in which Confederate forces defeated the Union troops. People in the North now realized the war would be a long one.

As commander in chief of the Army, Lincoln had to select an officer capable of organizing untrained volunteers into armies and leading them to victory. General George B. McClellan turned out to be a fine organizer. But his spring 1862 campaign, in which he attempted to capture Richmond, ended in failure. Lincoln then relieved McClellan of much of his command. General John Pope was made commander of troops in Virginia, but he was defeated in the second Battle of Bull Run (also called Manassas) on Aug. 29-30, 1862. Lincoln again called on McClellan to defend Washington. On September 17, “Little Mac” turned back the army of General Robert E. Lee in the Battle of Antietam. But McClellan then refused to move. In early November, Lincoln removed him for the second time and put General Ambrose E. Burnside in command. Burnside met defeat in the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13. His successor, General Joseph Hooker, lost the Battle of Chancellorsville on May 1-4, 1863.

Union forces made some progress only in the West, in the valley of the Mississippi River. There, General Ulysses S. Grant in 1862 took Fort Henry on February 6 and Fort Donelson on February 16. In early April, Grant’s troops forced a Confederate army to retreat in the Battle of Shiloh, but only after the Union army had suffered enormous losses.

Strengthening the home front.

Organization for military success was only one of Lincoln’s tasks. He also had to arouse popular support for the Union armies. Different opinions among the people became plain after their first enthusiasm wore off. Many Northerners were willing to fight to preserve the Union, but not to destroy slavery. Other Northerners demanded that the destruction of slavery should be the main goal.

Lincoln believed that the border states would secede if antislavery extremists had their way. This would mean the secession of Kentucky, Missouri, Delaware, and Maryland. The task of defeating the South would probably be impossible without these states. Besides, the Constitution protected slavery in the states where it already existed. Impulsive generals sometimes issued proclamations freeing enslaved people within their command, but Lincoln overruled them, believing that this power belonged to him alone. Lincoln’s moderate position helped keep the border states in the Union. Lincoln also managed to keep the support of the majority of Northerners, who favored fighting to preserve the Union over fighting to free the enslaved people.

Foreign relations.

While meeting his other challenges, Lincoln managed to keep a check on foreign policy. In 1861, Secretary of State Seward suggested that the United States could be unified by provoking several European nations to war. The president quietly ignored this proposal.

In November 1861, Captain Charles Wilkes of the U.S. Navy stopped the British ship Trent and removed two Confederate commissioners, James M. Mason and John Slidell. The British angrily demanded the release of the two men, and they prepared for war to support their demand. The United States later freed Mason and Slidell. Thus, Lincoln avoided a war that would have been disastrous to the United States. See Trent Affair.

Life in the White House.

To Lincoln, the presidency meant fulfillment of the highest ambition that an American citizen could have. However, the Civil War destroyed any hope he may have had for happiness in the White House. Aside from directing military affairs and stiffening the will of the North, he carried an enormous burden of administrative routine. His office staff was small. He wrote most of his own letters and all his speeches. He made decisions on thousands of political and military appointments. For several hours each week, he saw everyone who chose to call. During all his years in office, Lincoln was away from the capital less than a month.

Lincoln found some relaxation in taking carriage drives, and he enjoyed the theater. He regarded White House receptions and dinners more as duties than as pleasures. Lincoln’s frequent visits to army hospitals saddened him. Late at night, he sometimes found solace by reading works of Shakespeare or the Bible. But his official duties left little time for diversion.

To Mrs. Lincoln, life in the White House was a tragic disappointment. Her youngest brother, three half brothers, and the husbands of two half sisters were serving in the Confederate Army, and she faced constant suspicion of disloyalty. The pressures of everyday life weighed heavily on her high-strung nature. Jealousy and outbursts of temper cost her many friendships.

Two of Lincoln’s sons, William Wallace and Thomas, lived in the White House. For nearly a year, “Willie” and “Tad” enlivened the mansion with their laughter and pranks. Willie’s death on Feb. 20, 1862, grieved Lincoln deeply. Mrs. Lincoln could not be consoled. Lincoln’s oldest son, Robert, had been a student at Harvard when his father was elected. He remained there until February 1865, when he left law school to briefly serve on General Grant’s staff as a captain.

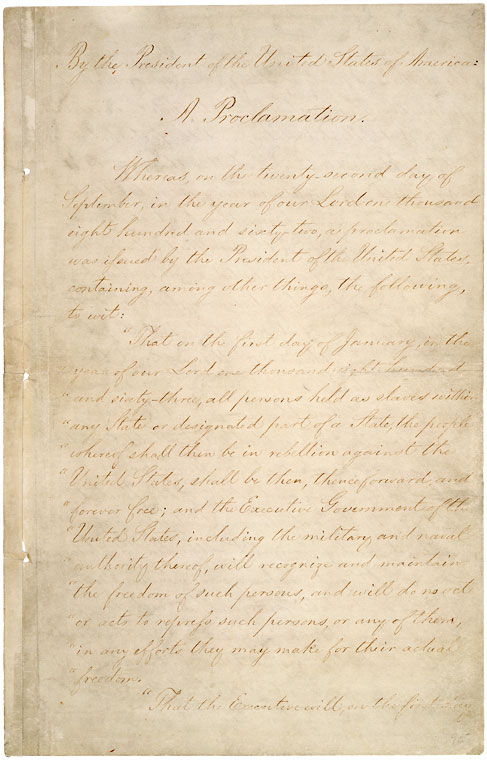

The Emancipation Proclamation.

By late summer of 1862, Lincoln was convinced that the time had come for a change in policy on slavery. Several foreign governments sympathized with the South. However, they condemned slavery as evil, and thus did not dare support the Confederacy. Emancipation would ensure these governments’ neutrality in America’s war.

At home, thousands of enslaved people had already begun fleeing their masters. Known as “contrabands,” these people had no legal status and presented Lincoln with a difficult situation. Lincoln believed that freed Black men could serve as Union soldiers. At the same time, a growing number of Northerners who had been indifferent to slavery now believed that it had to be stamped out. Lincoln finally decided to issue a proclamation freeing enslaved people. He did not ask the advice of his Cabinet, but he did tell the members what he intended to do. On Seward’s advice, he withheld the proclamation until a Northern military victory created favorable circumstances.

The Battle of Antietam, fought on Sept. 17, 1862, triggered the announcement. Lincoln issued a preliminary proclamation five days later. It declared that all enslaved people in states, or parts of states, that remained in rebellion on Jan. 1, 1863, would be free. He issued the final proclamation on January 1. Lincoln named the states and parts of states in rebellion, and declared that the enslaved people held there “are, and henceforward shall be, free.” See Emancipation Proclamation.

Actually, the proclamation freed no enslaved people on the day it was issued. It applied only to Confederate territory, where federal officers could not yet enforce it. The proclamation did not affect slavery in the loyal border states. But Lincoln repeatedly urged those states to free their enslaved people and to pay the owners for their loss. He promised financial help from the federal government for this purpose. The failure of the states to immediately follow his advice was one of his great disappointments. Maryland, however, did later move on its own to abolish slavery.

The Emancipation Proclamation eventually freed hundreds of thousands of people who had been held in slavery. Whenever Union troops took control of Southern territory, they liberated enslaved people in their path. The proclamation had a major long-range impact. In the eyes of other nations, it gave a new character to the war. In the North, it gave a high moral purpose to the struggle and paved the way for the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution. This amendment, adopted in December 1865, ended slavery in all parts of the United States.

The Gettysburg Address.

Union armies won two great victories in 1863. General George G. Meade’s Union forces defeated the Confederates under Lee at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, during the first three days of July. On July 4, Vicksburg, Mississippi, fell to Grant’s troops. This city had been the last Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River. “The Father of Waters again goes unvexed to the sea,” Lincoln declared.

On Nov. 19, 1863, ceremonies were held to dedicate a soldiers’ cemetery on the Gettysburg battlefield. The principal speaker was Edward Everett, one of the greatest orators of his day. He spoke for two hours. Lincoln was asked to say only “a few appropriate remarks,” and he spoke for about two minutes.

Gettysburg Address

Many writers have said that Lincoln scribbled his speech while traveling on the train to Gettysburg. This is not true. He prepared the address carefully, in advance of the ceremonies, although he revised the text in Gettysburg. Everett and many others knew at once that Lincoln’s ringing declaration that “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth” would live as long as democracy itself. For the complete text of the speech, see Gettysburg Address.

The victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg had seemed to promise an early peace. But the war went on. In March 1864, Lincoln put Grant in command of all the Union armies. The Army of the Potomac started to march toward Richmond two months later. At the same time, General William T. Sherman began his famous march from Tennessee to Atlanta, and then to the sea.

Election of 1864.

Grant met skillful resistance in the South, and his troops suffered thousands of casualties. Many people called him “the butcher” and condemned Lincoln for supporting him. In 1864, Lincoln skillfully turned back efforts by some fellow Republicans to replace him in the White House. Republicans and War Democrats—Democrats who supported Lincoln’s military policies—formed the Union Party. In June that year, the party nominated Lincoln for president. It selected former Senator Andrew Johnson of Tennessee, a leading War Democrat, for vice president. The Democrats chose the former General George B. McClellan as their candidate for president, and Representative George H. Pendleton of Ohio for vice president.

Lincoln became less popular as the summer wore on. Late in August, he confessed privately that “it seems exceedingly probable that this administration will not be reelected.” Then the military trend changed. Rear Admiral David G. Farragut had won the Battle of Mobile Bay on August 5, and Sherman’s troops captured Atlanta on September 2. A series of Union victories cleared Confederate forces from the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. In a famous duel off the coast of France, the U.S.S. Kearsarge sank the Confederate cruiser Alabama, which had preyed on Union merchant ships. Many discouraged Northerners took heart again.

The Union victories helped Lincoln win reelection. He defeated McClellan by an electoral vote of 212 to 21. He won the popular vote by more than 400,000 votes.

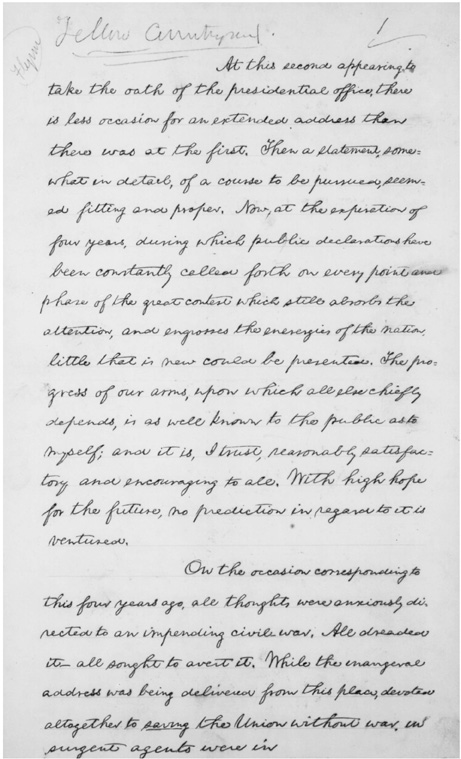

Second inauguration.

The end of the war was clearly in sight when Lincoln took the oath of office a second time, on March 4, 1865. Grant had besieged Lee’s weary troops at Petersburg, Virginia. The Southern armies were wasting away in Grant’s bulldog grip. Sherman left a wide track of destruction as he marched through Georgia and the Carolinas.

As a result, Lincoln could concentrate on reuniting the nation. In his second inaugural address, he explained that the Civil War had to be fought to abolish slavery. It was God’s will, he declared, that the North and South together pay the price for slavery. He urged the people to maintain their faith in God’s goodness and justice even if the war should continue “until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword. …” He closed with a moving plea for “malice toward none” and “charity for all,” North and South alike.

Photographs taken of Lincoln around the time of his second inauguration show the effect of four years of war. His face had become gaunt and deeply lined. He slept little during crises in the fighting, and his eyes were ringed with black. Lincoln ate his meals irregularly, and he had almost no relaxation.

In spite of his exhaustion, Lincoln continued to see widows and soldiers who called at the White House. His delight in rough humor never deserted him. More than once, he shocked members of his Cabinet by telling stories or reading to them from such humorists as Artemus Ward and Orpheus C. Kerr. Even so, the strain of melancholy that had first appeared in him as a young man deepened.

Lincoln came to have a quiet confidence in his own judgment as he met the trials of war. Still, he remained a man of genuine humility. The war brought out his best qualities, as he rose to each new challenge. Lincoln was a master politician, and he timed his actions to the people’s moods. He led by persuasion. Horace Greeley said: “He slowly won his way to eminence and fame by doing the work that lay next to him—doing it with all his growing might—doing it as well as he could, and learning by his failure, when failure was encountered, how to do it better.”

End of the war.

On April 9, 1865, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House in Virginia. Under authority from Lincoln, Grant extended generous terms to Lee and his army. A great wave of joy swept the North when the fighting ended. A few days before, Lincoln had quietly entered Richmond, accompanied by his son Tad. There, he was greeted as a savior by the city’s once-enslaved African Americans.

On the night of April 11, before a crowd that serenaded him, Lincoln spoke soberly of the future. Louisiana had applied for readmission to the Union under Lincoln’s plan of reconstruction. Many Northerners wanted to impose harsher terms on the state. Some complained that Black citizens would not receive the right to vote under Louisiana’s new government. “I would myself prefer,” said Lincoln, “that it [the vote] were now conferred on the very intelligent, and on those who serve our cause as soldiers.” The speech marked the first time an American president had spoken of extending the vote to Black citizens. An outraged member of the audience that night, infuriated by Lincoln’s speech, vowed to kill him. That man was John Wilkes Booth.

Many people insisted that Lincoln decide if “the seceded states, so called, are in the Union or out of it.” No matter, said the president in his last public address on April 11, 1865: “Finding themselves safely at home, it would be utterly immaterial whether they had ever been abroad.” Lincoln admitted that the new government of Louisiana was imperfect. But, he asked, “Will it be wiser to take it as it is and help improve it, or to reject and disperse it?”

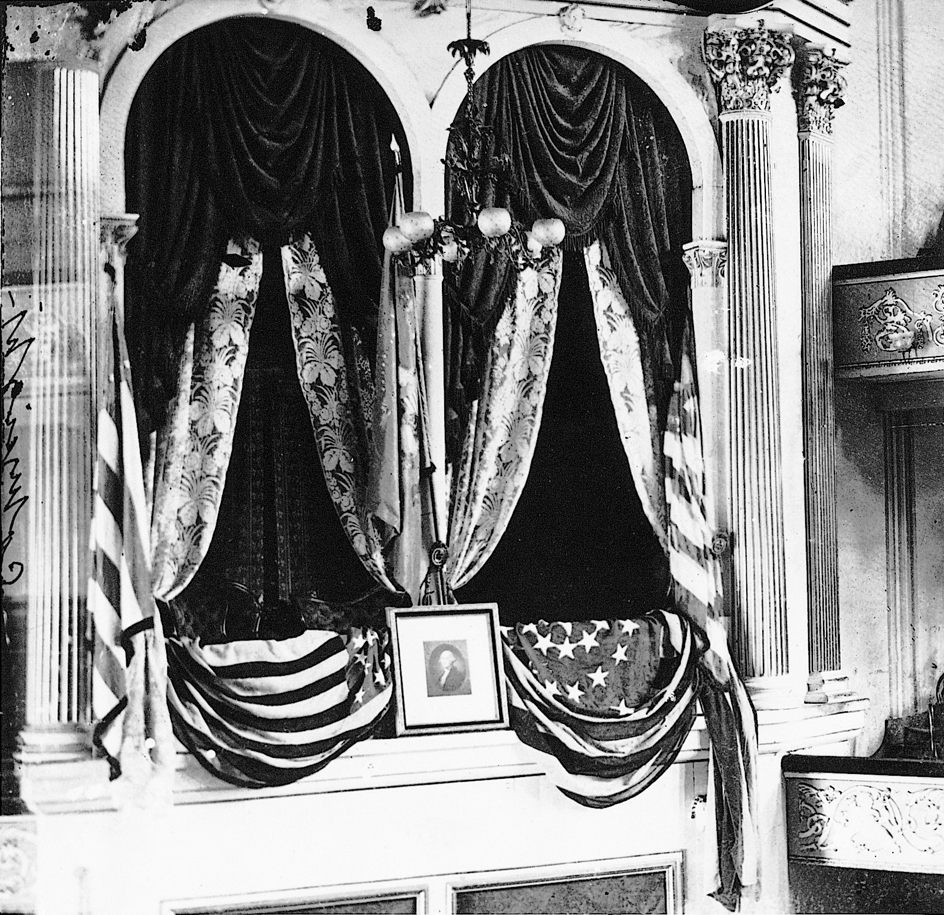

Assassination.

On the evening of April 14, 1865, Lincoln attended a performance of the comedy Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre in Washington. At 10:22 p.m., a shot rang through the crowded house. Booth, one of the best-known actors of the day, had shot the president in the head from the rear of the presidential box. In leaping to the stage, Booth caught his spur in a flag draped in front of the box. He fell and broke his leg. But he limped across the stage brandishing a dagger and crying: “Sic semper tyrannis” (Thus always to tyrants), the motto of Virginia.

Lincoln was carried unconscious to a boarding house across the street. Lincoln’s family and a number of high government officials surrounded him. Lincoln died at 7:22 a.m. on April 15.

As president, Lincoln had been bitterly criticized. After his death, however, even his enemies praised his kindly spirit and selflessness. Millions of people had called him “Father Abraham.” They grieved as they would have grieved at the loss of a father. The train carrying Lincoln’s body started north from Washington, to Baltimore, before heading west. Mourners lined the tracks as it moved across the country. Thousands wept as they looked upon him for the last time. On May 4, Lincoln was buried in Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield, Illinois. The monument over his grave is a place of pilgrimage, as are other spots that his life had touched in Kentucky, Indiana, Illinois, and, above all, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

The trial of the conspirators.

After shooting Lincoln, Booth fled to Maryland on horseback. A friend, David E. Herold, a former druggist’s clerk, joined Booth there and helped him escape to Virginia. On April 26, 1865, federal troops searching for Booth trapped the two men in a barn near Port Royal, Virginia. Herold surrendered, but Booth was shot and killed.

Several people were believed to have been involved with Booth in both Lincoln’s assassination and a plot to kill other government officials. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton ordered agents of his department to arrest them. Besides Herold, the accused conspirators included George Atzerodt, a carriage maker, for planning the murder of Vice President Andrew Johnson; Lewis Thornton Powell (also known as Lewis Payne or Paine), a former Confederate soldier, for attempting to kill Secretary of State Seward; and Mary E. Surratt, the owner of a Washington boarding house, for helping the plotters. Booth and the others supposedly planned the crimes in Surratt’s home.

The Department of War also accused Samuel Arnold and Michael O’Laughlin, boyhood friends of Booth’s, of helping him plan the crimes. Samuel A. Mudd, a Maryland physician who had set Booth’s broken leg after the assassination of Lincoln, was charged with aiding the plotters. Edman (also known as Edward or Ned) Spangler, a stagehand at Ford’s Theatre, was charged with helping Booth escape. Some people accused Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his secret service of approving and funding the plot, but the charges were never proved.

A nine-man military commission tried the accused conspirators in Washington. The trial began on May 10, 1865, and lasted until June 30. The commission convicted all eight defendants and sentenced Atzerodt, Herold, Powell, and Surratt to death. They were hanged on July 7. Arnold, Mudd, and O’Laughlin received sentences of life imprisonment, and Spangler received a six-year sentence. O’Laughlin died in prison of yellow fever in 1867. President Johnson pardoned Arnold, Mudd, and Spangler in 1869.

Presidential library.

The library portion of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum opened in Springfield, Illinois, in 2004. The library serves as a center for research and study about Lincoln. The museum, which opened in 2005, offers interactive exhibits and dramatic presentations about Lincoln’s life and times.