Lindbergh, Charles Augustus (1902-1974), an American aviator and airmail pilot, made the first solo nonstop flight across the Atlantic Ocean on May 20-21, 1927. Other pilots had crossed the Atlantic before him. But Lindbergh was the first person to do it alone nonstop.

Lindbergh’s feat gained him immediate international fame. The press named him “Lucky Lindy” and the “Lone Eagle.” Americans and Europeans idolized the shy, slim young man and showered him with honors.

Before Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941, Lindbergh campaigned against voluntary American involvement in World War II. Many Americans criticized him for his noninvolvement beliefs. After the war, he avoided publicity until the late 1960’s, when he spoke out for the conservation of natural resources. Lindbergh served as an adviser in the aviation industry from the days of wood and wire airplanes to supersonic jets.

Early life.

Charles Augustus Lindbergh was born on Feb. 4, 1902, in Detroit. He grew up on a farm near Little Falls, Minnesota. He was the son of Charles August Lindbergh, a lawyer, and his wife, Evangeline Lodge Land. Lindbergh’s father served as a U.S. congressman from Minnesota from 1907 to 1917.

In childhood, Lindbergh showed exceptional mechanical ability. At the age of 18, he entered the University of Wisconsin to study engineering. But Lindbergh was more interested in the field of aviation than he was in school. After two years, he left school to become a barnstormer, a pilot who performed daredevil stunts at fairs.

In 1924, Lindbergh enlisted in the United States Army so that he could be trained as an Army Air Service Reserve pilot. In 1925, he graduated from the Army’s flight-training school at Brooks and Kelly fields, near San Antonio, as the best pilot in his class. After Lindbergh completed his Army training, the Robertson Aircraft Corporation of St. Louis hired him to fly the mail between St. Louis and Chicago. He gained a reputation as a cautious and capable pilot.

His historic flight.

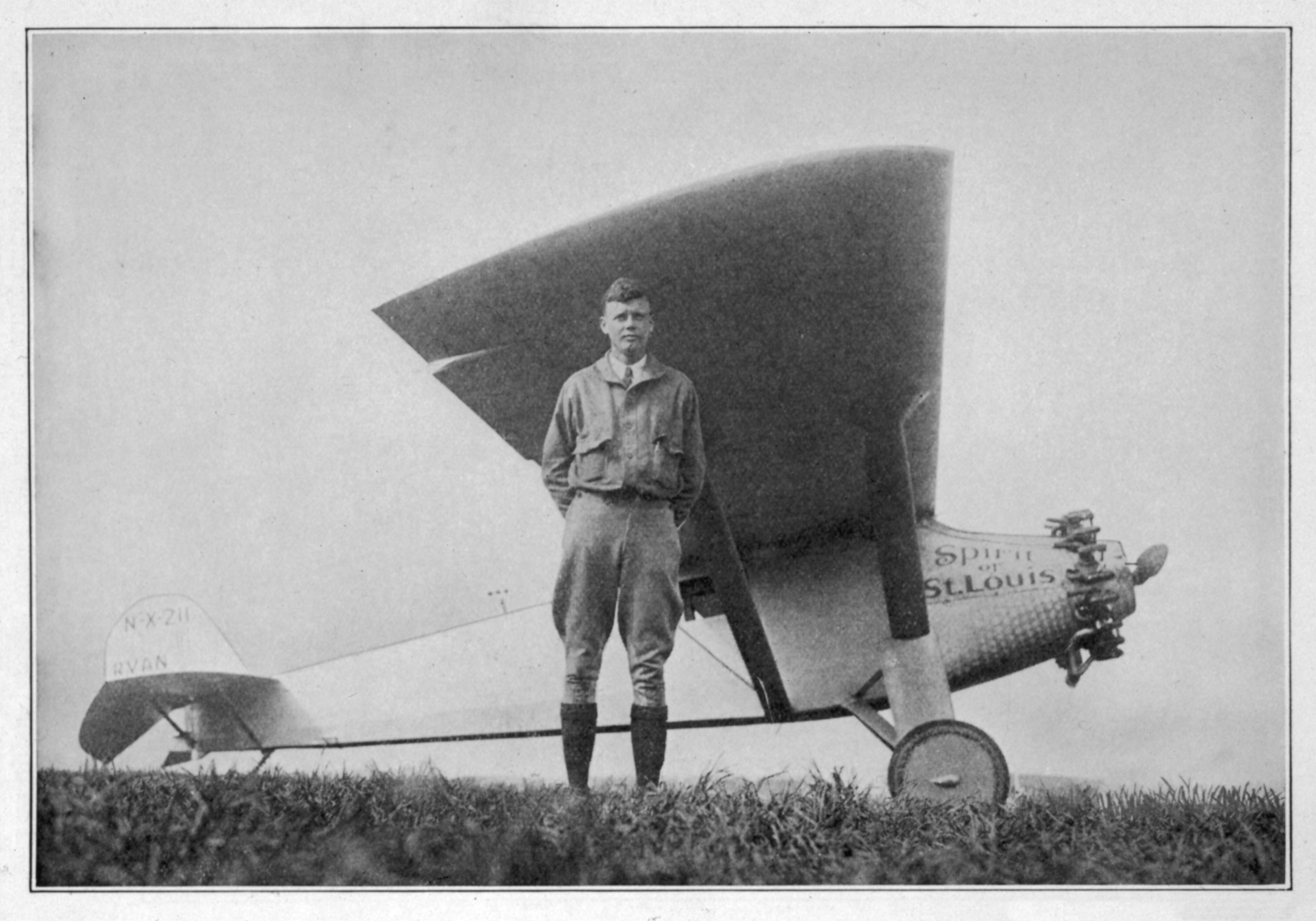

In 1919, a New York City hotel owner named Raymond Orteig offered $25,000 to the first aviator to fly nonstop from New York to Paris. Several pilots were killed or injured while competing for the Orteig prize. By 1927, it had still not been won. Lindbergh believed he could win it if he had the right airplane. He persuaded nine St. Louis businessmen to help him finance the cost of a plane. Lindbergh approached a number of major aircraft manufacturers, but they all refused to sell him a plane. He then selected the Ryan Aeronautical Company of San Diego to manufacture a special plane, which he helped design. He named the plane the Spirit of St. Louis. On May 10-11, 1927, Lindbergh tested the plane by flying from San Diego to New York City, with an overnight stop in St. Louis. The flight took 20 hours 21 minutes, a transcontinental record.

On May 20, Lindbergh took off in the Spirit of St. Louis from Roosevelt Field, near New York City, at 7:52 A.M. He landed at Le Bourget Field, near Paris, on May 21 at 10:21 P.M. Paris time (5:21 P.M. New York time). Thousands of cheering people had gathered to meet him. He had flown more than 3,600 miles (5,790 kilometers) in 331/2 hours.

Loading the player...Charles Lindbergh with the Spirit of St. Louis

Lindbergh’s heroic flight thrilled people throughout the world. He was honored with awards, celebrations, and parades. President Calvin Coolidge gave Lindbergh the Distinguished Flying Cross. By act of Congress, he was awarded the Medal of Honor.

In 1927, Lindbergh wrote We, an autobiography that was published that same year. Also in 1927, Lindbergh flew throughout the United States to encourage air-mindedness on behalf of the Daniel Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics. Lindbergh learned about the pioneer rocket research of Robert H. Goddard, a Clark University physics professor. Lindbergh persuaded the Guggenheim family to support Goddard’s experiments, which later led to the development of missiles, satellites, and space travel. Lindbergh also worked for several airlines as a technical adviser.

Good-will ambassador.

At the request of the U.S. government, Lindbergh flew to various Latin American countries in December 1927 as a symbol of American good will. While in Mexico, he met Anne Spencer Morrow, the daughter of Dwight W. Morrow, the American ambassador. Lindbergh married Anne Morrow in 1929. He taught her to fly, and they went on many flying expeditions together throughout the world, charting new routes for various airlines. Anne Morrow Lindbergh also became famous for her poetry and other writings. See Lindbergh, Anne Morrow.

Lindbergh invented an “artificial heart” between 1931 and 1935. He developed it for Alexis Carrel, a French surgeon and biologist whose research included experiments in keeping organs alive outside the body. Lindbergh’s device could pump the substances necessary for life throughout the tissues of an organ. See Carrel, Alexis .

The Lindbergh kidnapping.

On March 1, 1932, the Lindberghs’ 20-month-old son, Charles Augustus, Jr., was kidnapped from the family home in New Jersey. About ten weeks later, his body was found. In 1934, police arrested a carpenter, Bruno Richard Hauptmann, and charged him with the murder. Hauptmann was convicted of the crime. He was executed in 1936.

The press sensationalized the tragedy. Reporters, photographers, and curious onlookers harassed the Lindberghs constantly. In 1935, after the Hauptmann trial, Lindbergh, his wife, and their 3-year-old son, Jon, moved to Europe in search of privacy and safety.

The Lindbergh kidnapping led Congress to pass the “Lindbergh law.” This law makes kidnapping a federal offense if the victim is taken across state lines or if the mail service is used for ransom demands.

World War II.

While in Europe, Lindbergh was invited by the governments of France and Germany to tour the aircraft industries of their countries. Lindbergh was especially impressed with the highly advanced aircraft industry of Nazi Germany. In 1938, Hermann Goring, a high Nazi official, presented Lindbergh with a German medal of honor. Lindbergh’s acceptance of the medal caused an outcry in the United States among critics of Nazism.

Lindbergh and his family returned to the United States in 1939. In 1941, he joined the America First Committee, an organization that opposed voluntary American entry into World War II. Lindbergh became a leading spokesman for the committee. He criticized President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s foreign policies. He also charged that British, Jewish, and pro-Roosevelt groups were leading America into war. Lindbergh resigned his commission in the Army Air Corps after Roosevelt publicly denounced him. Some Americans accused Lindbergh of being a Nazi sympathizer because he refused to return the medal he had accepted from Goring.

After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, Lindbergh stopped his noninvolvement activity. He tried to reenlist, but his request was refused. He then served as a technical adviser and test pilot for the Ford Motor Company and United Aircraft Corporation (now United Technologies Corporation).

In April 1944, Lindbergh went to the Pacific war area as an adviser to the United States Army and Navy. Although he was a civilian, he flew about 50 combat missions. Lindbergh also developed cruise control techniques that increased the capabilities of American fighter planes.

After the war,

Lindbergh withdrew from public attention. He worked as a consultant to the chief of staff of the U.S. Air Force. President Dwight D. Eisenhower restored Lindbergh’s commission and appointed him a brigadier general in the Air Force in 1954. Pan American World Airways also hired Lindbergh as a consultant. He advised the airline on its purchase of jet transports and eventually helped design the Boeing 747 jet. In 1953, Lindbergh published The Spirit of St. Louis, an expanded account of his 1927 transatlantic flight. The book won a Pulitzer Prize in 1954.

Lindbergh traveled widely and developed an interest in the cultures of peoples in Africa and the Philippines. During the late 1960’s, Lindbergh ended his years of silence to speak out for the conservation movement. He especially campaigned for the protection of humpback and blue whales, two species of whales in danger of becoming extinct. Lindbergh opposed the development of supersonic transport planes because he feared the effects the planes might have on the atmosphere of the earth.

Lindbergh died of cancer on Aug. 26, 1974, in his home on the Hawaiian island of Maui. The Autobiography of Values, a collection of Lindbergh’s writings, was published in 1978.

In 2001, three adult children of a German woman claimed that Lindbergh was their father. DNA tests in 2003 confirmed that the three—two men and a woman born in 1958, 1960, and 1967—were related to Lindbergh. In 2005, the three Germans suggested that Lindbergh had fathered four other children by two different German women during the same period, when he was married to Anne Morrow Lindbergh.

See also Airplane (History) ; Lindbergh, Anne Morrow .