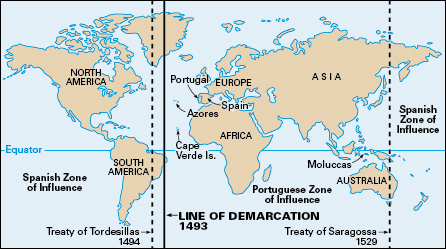

Line of Demarcation was an imaginary line drawn by Pope Alexander VI to settle land claims. The line was drawn in 1493, after Christopher Columbus returned from his first voyage to the Americas. The pope hoped it would prevent disputes between Spain and Portugal over new lands discovered by Spanish and Portuguese explorers. The line ran from north to south at points west of the Azores and Cape Verde Islands. It barely touched the east coast of the South American mainland, which had not yet been discovered by Europeans. Spain was permitted to claim land to the west of the line, and Portugal could claim land to the east of the line.

Neither nation found this settlement satisfactory. So the next year Spain and Portugal moved the line farther west by the Treaty of Tordesillas. Both countries thought the line’s new location was about midway between Portugal’s claims on the Cape Verde Islands and Columbus’s new discoveries. However, nobody yet knew the actual size or shape of the Atlantic Ocean. The line was never surveyed, so its exact location was not determined. Scholars think that it lay near the 48° west longitude line.

The Treaty of Tordesillas later supported Portugal’s claim to territory that is now eastern Brazil. A continuation of the Line of Demarcation around the globe and into the Eastern Hemisphere gave Portugal the right to claim the Philippine Islands. Spain recognized this claim in the Treaty of Saragossa in 1529, which set the line 17° east of the Moluccas (Spice Islands). In later treaties with Spain, Portugal gave up its claim to the Philippines and won the rest of Brazil. But Portugal and Spain could not secure all the newly discovered lands, because France, England, and the Netherlands ignored the Line of Demarcation and claimed territory for themselves.