Locomotive is a machine that moves trains on railroad tracks. It is sometimes called a railroad engine. Locomotives of the early 1830’s weighed from 5 to 8 tons (4.5 to 7.3 metric tons) and could pull or push only a few light cars. A modern diesel locomotive may weigh over 210 tons (190 metric tons). Modern locomotives often use multiple-unit operation. In multiple-unit operation, two or more locomotives are linked together under the control of a single engineer. Several modern diesel locomotives working together in multiple-unit operation can pull 200 or more loaded freight cars at one time.

A locomotive by itself, or a locomotive with a permanently attached fuel car called a tender, is not a train. The term train refers to a combination of railroad cars or to a combination of at least one locomotive coupled to one or more cars for passengers or freight. A train can also consist of self-propelled cars that do not require a separate locomotive.

Loading the player...A steam locomotive

Kinds of locomotives

Locomotives may be grouped by the type of work they do. Road locomotives haul trains over long distances. They include passenger locomotives and freight locomotives. Passenger locomotives pull trains designed to carry travelers. In addition, passenger locomotives often supply electric current to passenger cars for lighting, heating, and air conditioning. Freight locomotives pull cars designed to carry heavy cargo, such as grain, coal, liquids, manufactured goods, lumber, highway trailers, and freight containers. Switching locomotives move cars from track to track in railroad yards. They are typically not as powerful as road locomotives. Freight and switching locomotives can also pull work trains that repair railroad tracks or clear snow.

Locomotives can also be grouped according to their source of power. The three major types include: (1) diesel, (2) electric, and (3) steam. A fourth kind of power source is the gas turbine, a form of jet engine that can drive a generator to make electricity. Gas turbines combined with generators are used to power some lightweight, self-propelled rail cars that carry passengers. Individual locomotives of the three major types generally range from about 400 horsepower (300 kilowatts) to 6,000 horsepower (4,500 kilowatts), though some provide over 10,000 horsepower (7,500 kilowatts).

Diesel locomotives

are the most common type of locomotive worldwide. Diesel engines generally convert fuel to energy more efficiently than engines that burn other fuels.

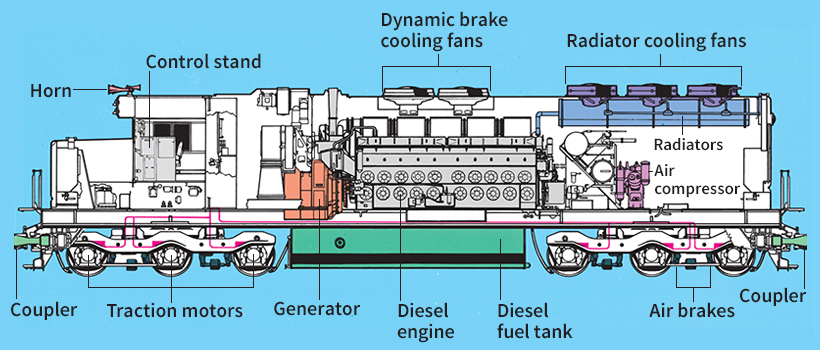

The most common kind of diesel locomotive is the diesel-electric locomotive. Diesel-electric locomotives function like traveling power plants. In a diesel-electric locomotive, a powerful diesel engine drives a large electric generator.

Each axle of a modern diesel-electric locomotive is fitted with a traction motor, a compact, specialized electric motor. The generator sends a powerful electric current to each traction motor. Each motor uses a pair of gears to turn the axles on the locomotive’s driving wheels. The driving wheels move the train.

The engineer controls the speed of a diesel-electric locomotive by using levers for the vehicle’s throttle and dynamic brake. The throttle lever increases or decreases the power output of the diesel engine, which, in turn, varies the amount of current produced by the generator. When the amount of current sent to the traction motors increases, the train goes faster. Application of the dynamic brake causes the traction motors to function temporarily as generators. The spinning motion of the locomotive’s axles is thus converted into electric current, creating electrical resistance. This resistance against the turning axles slows the train. Locomotives are equipped with both dynamic brakes and air brakes. Air brakes are a series of brakes connected by pneumatic lines (hoses that hold pressurized air). All the cars in a train have air brakes. The engineer activates the air brakes from the locomotive by using controls to change the air pressure in the pneumatic lines. If there is a loss of air pressure, the air brakes all activate automatically.

Diesel locomotives frequently run in multiple-unit operation. Electrical and pneumatic lines connect the units (locomotives) so that all controls operate from the lead unit. Connected this way, two to six freight locomotives commonly pull trains weighing from 5,000 tons (4,550 metric tons) to more than 20,000 tons (18,100 metric tons).

Sometimes, two or more remote control units help pull extremely long freight trains. These units are located near the middle of the train. The engineer controls them from the lead unit using radio signals. On steep slopes, pusher units, also called helper units, assist long freight trains. One or more pusher units under the control of a separate crew may push at the rear of a freight train going uphill. Such units may also assist with extra dynamic braking when a train is going downhill.

Early diesel-electric locomotives used generators that produced direct current (DC), a kind of current that flows in only one direction. More efficient generators producing alternating current (AC), current that reverses direction many times per second, have been used in locomotives since the 1970’s. Until the 1990’s, most traction motors operated on direct current. Locomotives with AC generators used devices that rectified (converted) the alternating current into direct current before it went to the motors. Today, many locomotives use computer-controlled AC traction motors. These motors can produce greater power at each driving axle and do not overheat as easily as DC traction motors.

In modern diesel-electric locomotives, computers control fuel flow, engine efficiency, and traction at the driving wheels. As a result, these locomotives can produce more power using less fuel than older ones can. Electronic traction-control systems help prevent wheel slipping and allow the highest torque (rotating force) to be applied to the driving wheels.

Two other kinds of diesel locomotives are diesel-hydraulic locomotives and diesel-mechanical locomotives. Diesel-hydraulic locomotives use fluid under pressure to transmit power from the engine to the driving wheels. A diesel-mechanical locomotive transmits power to the driving wheels using a system of gears and rods, much like an ordinary automobile engine does. Neither of these two types of locomotives is widely used today.

Electric locomotives,

unlike diesels, do not produce their own power. They use electric current supplied by a stationary central generating station. This station is a power plant that produces electric current using coal, natural gas, water power, nuclear energy, or petroleum. Alternating current generated at the station flows through a contact wire. A system of suspension wires holds the contact wire over the railroad tracks at an even height. The contact wire, together with the suspension wires, is called the catenary.

The roof of each locomotive carries one or two pantographs, hinged devices that collect current from the contact wire. Inside the body of the locomotive, the current passes through one or more transformers. Transformers step down (reduce) the voltage to that required by the motors. The current is then fed to AC traction motors, or it is rectified and fed to DC traction motors. Like diesels, electric locomotives can either run singly or be combined in multiple-unit operation.

Electric locomotives are numerous in China, Japan, several European nations, and a few other countries. The trains they power include some of the world’s fastest—including France’s TGV (train a grande vitesse), Japan’s Shinkansen, Germany’s ICE (Inter-City Express) train, Sweden’s X2000, and the Acela in the United States.

An electrified railway network is expensive to build and maintain. Throughout the world, the construction and maintenance of most electrified railroads has required government support.

Steam locomotives.

Steam engines powered the first locomotives ever built. These engines burn coal, fuel oil, or wood in a special furnace called a firebox. The heat turns water in the engine’s boiler into steam. In many locomotives, the steam is then superheated (heated beyond boiling temperature) before being fed into two or more cylinders. In each cylinder, the steam pushes against a disc called a piston. Special valves control the flow of steam, causing it to press against one side of the piston and then the other. This alternating pressure creates a reciprocating (back-and-forth) motion. See Steam engine (Reciprocating steam engines) .

Steam locomotives use connectors called main rods and side rods to transmit power from the pistons to the driving wheels. Most steam locomotives have a permanently attached tender that carries fuel and water for the firebox and boiler.

From the 1830’s until the 1950’s, steam locomotives pulled nearly all railroad trains. However, steam locomotives proved less reliable and less efficient than more modern locomotives. Most steam locomotives in use today pull special excursion trains for tourists and railroad enthusiasts. In a few countries, steam locomotives still haul freight or passenger trains in remote areas.

History

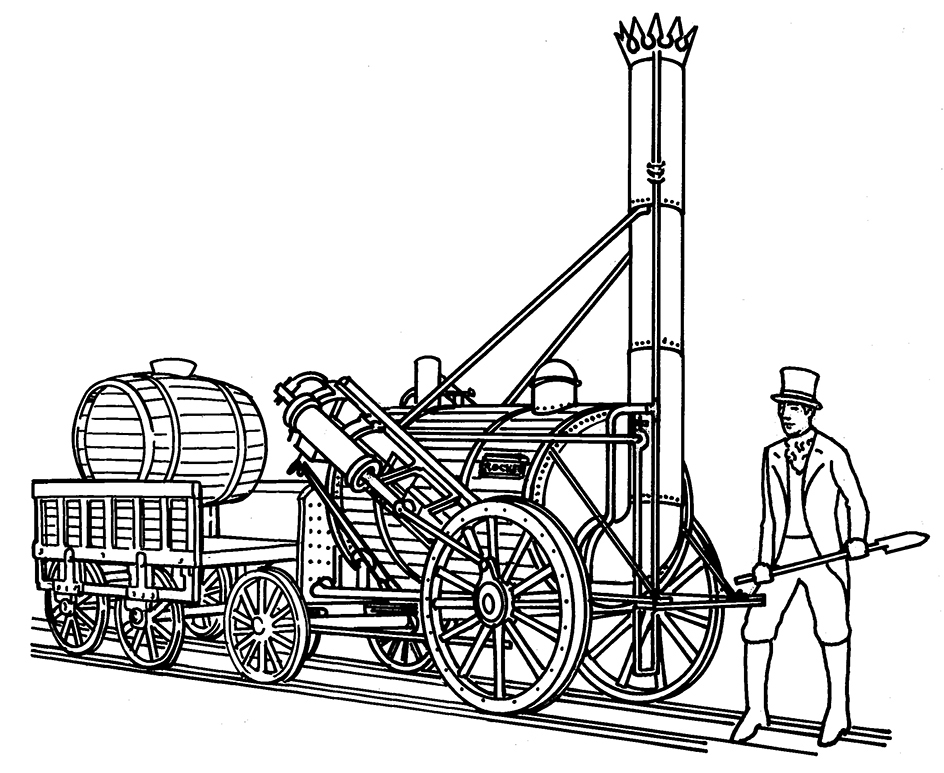

The earliest locomotives were invented and developed in the United Kingdom. The British engineer Richard Trevithick built a steam locomotive in 1804. Steam locomotives were hauling cars around British coal mines by 1813. In 1829, the British engineer Robert Stephenson designed and built the Rocket, the first steam locomotive suitable for high-speed, long-distance use. That year, a canal company in New York imported four British locomotives for use in Pennsylvania. One of these, the Stourbridge Lion, became the first locomotive to operate on a commercial railroad in the United States.

In late 1830, a rail line in Charleston, South Carolina, bought a locomotive from a foundry in New York. The locomotive, called The Best Friend of Charleston, soon began regular operation. Railroad systems developed rapidly in France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The Baltimore and Ohio, the first U.S. railroad company, began using locomotives in the early 1830’s.

In 1893, the New York Central locomotive 999 became the first vehicle to travel faster than 100 miles (160 kilometers) per hour. By 1900, locomotives transported 80 to 90 percent of all people and cargo traveling between U.S. cities. In 1920, nearly 70,000 locomotives, most of them steam-powered, operated throughout the United States.

In the late 1800’s, many inventors tried to develop an electric locomotive. The American inventor Thomas Edison tested his first model in 1880. The first electric street railway began operating in Germany in 1881. In 1895, the Baltimore and Ohio put electric locomotives into daily use. In the early 1900’s, a few U.S. railroads converted long sections of rail line to electric operation in parts of the East and the Pacific Northwest. In Europe, short distances between major cities favored the spread of electric rail lines.

Engineers began seriously to develop diesel locomotives in the early 1920’s. In 1925, the first diesel in regular use in the United States began switching operations in a New York City freight yard. The first passenger diesel train in the United States, the Burlington Railroad’s Zephyr, entered service in 1934. Diesel locomotives began hauling heavy freight in 1939. Diesel locomotives proved their reliability and economy during World War II (1939-1945). They helped handle the huge amounts of domestic rail traffic and large shipments of military supplies demanded by the war effort. Manufacturers also continued to build steam locomotives. The heaviest and most powerful steam locomotives ever, the Big Boys and the Alleghenys, were designed in 1941 and served until the 1950’s. By 1947, 90 percent of new locomotives were diesel. In 1960, the last steam locomotives in general use in the United States and Canada were retired.

Today’s diesel locomotives have advanced well beyond those of the 1940’s and 1950’s. Computerized traction-control systems and more efficient engines and motors have helped increase power and improve fuel economy. Better brakes and on-board diagnostic systems have made rail travel safer.

Today, in France and Japan, electric-powered trains run daily at speeds of 180 miles (290 kilometers) per hour or more. Research engineers work to further improve the safety, reliability, and economy of both diesel and electric locomotives.