Athens << ATH ihnz or ATH uhnz >> (pop. 634,452; met. area pop. 3,146,166) is one of the world’s most famous and historic cities. It became the capital of Greece in 1833, after the Greeks freed themselves from Ottoman rule. But Athens’s greatest fame dates from the 400’s B.C., when it was the world’s most powerful and most highly civilized city. The city’s name in Greek is Athinai.

Athens lies on a plain near the southern end of Attica, a peninsula that extends from southeastern Greece into the Aegean Sea. A crescent of mountains up to 4,600 feet (1,400 meters) high bounds Athens on the west, north, and east. Athens is about 5 miles (8 kilometers) from Piraeus, Greece’s largest seaport.

When Greece gained independence in 1829, Athens had only a few thousand people. The modern city dates from the reign of Otto I, a Bavarian prince who became the first ruler of the new Greek kingdom. Otto was king of Greece from 1832 to 1862. Under his direction, German architects planned and built modern Athens.

Ancient Athens was the leading cultural center of the Greek world. Many of the most gifted writers of Greece lived there. They wrote works of drama, history, lyric poetry, and philosophy that have influenced literature for centuries. Athenian architects built masterpieces of classical beauty, and the ruins of many of these structures may still be seen. The government of ancient Athens provided an example of democracy that has inspired lawmakers ever since. The ancient Athenian statesman Pericles called Athens the “school of Greece.” In many ways, the city was the birthplace of Western civilization.

The modern city

Landmarks.

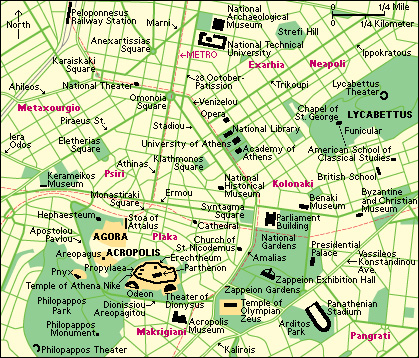

The bustling life of modern Athens centers around the city’s three main squares—Syntagma, Omonoia, and Monastiraki. Syntagma Square, or Constitution Square, is the administrative center of Athens. The Parliament Building, formerly the royal palace, faces Syntagma. In 1843, the Greek Constitution was proclaimed from the balcony of this building. A special corps of Greek soldiers, called evzones, guards the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and the Parliament Building. The evzones wear a colorful traditional uniform including a red tasseled cap, embroidered vest, white kilt, and red leather slippers. Hotels and office buildings also face Syntagma.

Omonoia Square, also known as Concord Square, lies about 1/2 mile (0.8 kilometer) northwest of Syntagma. The area between Omonoia Square and Syntagma Square is Athens’s chief shopping center. Omonoia Square has numerous department stores, restaurants, and other businesses. Main streets and trolley lines branch out from Omonoia.

South of Omonoia lies Monastiraki Square, the heart of an old market district. Numerous small shops, open-air stalls, and street vendors surround Monastiraki. To the southeast is the Plaka, a district that dates from the time when the Ottoman Empire, based in what is now Turkey, controlled Greece. The Plaka still shows Ottoman influence in its winding, cobblestoned alleys. But today it also hosts many nightclubs and hotels.

People.

Athens ranks as the cultural center of Greece, and large numbers of foreigners live in the city or visit there. As a result, Athens has an international atmosphere and a more modern style of life than any other Greek city.

The great majority of Athenians, like more than 95 percent of all Greeks, belong to the Greek Orthodox Church. Athens has many churches. The largest is the Cathedral, begun in 1840 and completed in 1855. The church of Saint Nicodemus dates from the early 1000’s.

Athenian food is similar to food served in other eastern Mediterranean regions. The people of Athens eat lamb prepared in many different ways, as well as a great variety of fish and other seafood. Other popular Greek specialties include feta, a cheese made from sheep’s or goat’s milk, and retsina, a wine flavored with pine resin.

Most Athenians live in small apartments or inexpensive houses. Many of the people own an automobile, but most of them ride the city’s buses and trolleys or the subway that serves Athens and surrounding areas.

Education and cultural life.

Athens has many public schools and several institutions of higher learning. The University of Athens, founded in 1837, has schools of law, medicine, philosophy, theology, and mathematics and the physical sciences. At the National Technical University of Athens, students study engineering and other subjects not taught at the University of Athens.

Next door to the National Technical University stands the National Archaeological Museum, one of the world’s greatest museums. It houses masterpieces of jewelry, pottery, and sculpture from all areas and every period of ancient Greece. The Acropolis Museum is home to some of Athens’s most treasured artifacts. Other museums include the Benaki Museum, which features art objects from medieval and modern Greece, and the Byzantine and Christian Museum.

The city’s archaeological schools have won worldwide fame, especially the American School of Classical Studies at Athens and the British School at Athens. These two schools, founded in the 1880’s, conduct excavations and train archaeologists.

Economy.

Athens is the economic and financial center of Greece. It is the headquarters for the nation’s major corporations, including insurance companies and research institutions. Tourism is the single largest source of income for the city, which hosts millions of visitors each year. Goods manufactured in the metropolitan area include cement, chemicals, clothing, electronic equipment, food products, machinery, medicines, military supplies, petroleum products, pharmaceuticals, ships, and textiles. The city also produces brassware, copperware, furs, jewelry, and a wide variety of other items popular with tourists.

The ancient city

The Acropolis and its buildings.

The ancient Greeks built Athens upon and around a great flat-topped, rocky hill. This hill, which covers a little more than 10 acres (4 hectares), became known as the Acropolis. The Greek words akro and polis mean high city, and the early rulers of Athens probably lived on the steep, easily defended hill. Through the years, the Athenians built temples and public buildings on the Acropolis, and people stopped living there.

By about 1200 B.C., the Athenians had erected a wall around most of the Acropolis. Parts of the wall still stand, but a series of larger walls replaced it during the 400’s B.C. About 530 B.C., the Athenians built a temple on the Acropolis and dedicated it to Athena, the patron goddess of the city. The temple was Athens’s largest building until 480 B.C. That year, a Persian army captured the city and destroyed most of the buildings on the Acropolis. In 447 B.C., the people of Athens began to rebuild the Acropolis site under the leadership of the great statesman Pericles. They erected many new structures, including the magnificent Parthenon, a marble temple dedicated to Athena (see Parthenon).

Pericles also began the Propylaea, the huge monumental entrance to the Acropolis. In 431 B.C., the Peloponnesian War interrupted its construction, and the Propylaea was never completed. To its right stands the small temple of Athena Nike. The Erechtheum, a temple built in several joining sections, stands about 60 yards (55 meters) from the Parthenon. It was completed about 400 B.C. The Athenians dedicated it to Athena, the god Poseidon, and Erechtheus, a legendary king of early Athens. The most famous part of the Erechtheum is the south porch, where six columns in the form of standing maidens hold up the roof. Cement copies have replaced the original marble figures. Most of the original figures were moved to the Acropolis Museum in the early 1980’s for protection from air pollution.

Other buildings.

The Temple of Olympian Zeus, the largest temple ever built in Greece, stood about 400 yards (370 meters) east of the Theater of Dionysus. The Athenian tyrant Pisistratus began the structure about 530 B.C., but many interruptions delayed it. The temple was finally completed during the reign of the Roman emperor Hadrian, who ruled from A.D. 117 to 138. The building had 104 columns, each 56 feet (17 meters) high, but only 16 of them remain today.

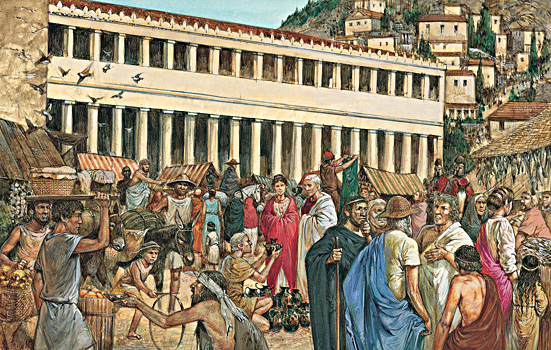

Northwest of the Acropolis was the Agora, the marketplace of ancient Athens. Archaeologists have uncovered the ruins of many of the Agora’s public buildings. Along the east side of the Agora stood the Stoa of Attalus, a long, roofed colonnade (row of marble columns) that housed many shops. It was built between 159 B.C. and 138 B.C. and was restored in the A.D. 1950’s. Today the Stoa of Attalus serves as a museum and as headquarters for excavations of the Agora. Just outside the Agora stands the Temple of Hephaestus (also called the Hephaesteum or Theseum), built about 449 B.C. It remains the best-preserved temple in Greece.

History

Earliest times.

Scholars know little about the history of Athens before about 1900 B.C., when Greeks first occupied Attica. Later invaders never drove out the Greek settlers, as they did in other parts of Greece.

Athens was one of the first city-states. Each of these independent states consisted of a city and the region that surrounded it. Athens had a king, as did other Greek states. According to tradition, the first king of Athens was named Cecrops. Kings ruled the city-state until 682 B.C. Beginning that year, elected officials called archons headed the government of Athens. The general assembly, which consisted of all adult male citizens of Athens, elected the archons to one-year terms. At first, a group of three archons managed the affairs of Athens. In time, the people increased the group to nine.

After their term of office, the archons joined the Areopagus, a council of elder statesmen. The Areopagus judged murder trials and prepared political matters for the vote of the general assembly. See Areopagus.

As Athens’s population grew, the farmers of Attica could not provide enough food for all the people and for themselves. The ruling aristocracy gradually acquired the best farmlands. Many small farmers went into debt and borrowed food that they promised to pay back out of the next year’s crop. Some, who could not pay their debts, even lost their land and became slaves. Civil war threatened to break out between the lower classes and the wealthy Athenians.

Solon, one of the archons of 594 B.C., made several important reforms. First he canceled all debts, thus freeing the people who had fallen into slavery. But they did not get their land back. Solon also set up qualifications for public office based on wealth. Any qualified citizen could become a public official, regardless of whether he belonged to the traditional ruling class. In addition, Solon reorganized and published all the laws of Athens.

Solon’s work did not solve the problem of poverty in Attica. Around 561 B.C., Pisistratus, a respected army commander, seized power and made himself tyrant (see Tyranny). He fell from power twice but ruled firmly from about 546 B.C. until his death in 528 or 527 B.C. The lower classes supported Pisistratus, and he repaid his followers by distributing land taken from his wealthy opponents. He thus continued the work of Solon in sharply reducing the power of the traditional ruling class. Pisistratus controlled, but did not suspend, the regular government and the archons. He made himself popular by making various improvements in the city, including construction of the first stages of the Temple to Zeus. After Pisistratus’ death, his son Hippias ruled as tyrant.

Democracy.

Hippias fell from power in 510 B.C., and Cleisthenes, the head of a leading family, became the most powerful statesman in Athens. About 508 B.C., the Athenians adopted a new constitution proposed by Cleisthenes, which made the state a democracy. This constitution was an unwritten one, but it stayed in effect with little change for hundreds of years. The constitution kept the ideas of Solon, but it also provided for new conditions that had developed since Solon’s rule.

Until Cleisthenes’s time, citizenship in Athens had been based on blood relationship to the four Ionic tribes that had originally settled Attica. A man had to belong to a phratry (brotherhood) to be a citizen. Under Cleisthenes’s system, all men 18 years of age and older were registered as citizens and as members of the deme (village or town) in which they lived. In time, membership in the demes became hereditary, and so a man might belong to a deme in which he did not actually live. Cleisthenes divided the demes into 30 groups called trittyes, which, in turn, were grouped into 10 new tribes. Each of the 10 tribes was made up of 3 trittyes from different regions of Athens. Thus, members of each tribe came from various families and different parts of the city-state.

Cleisthenes’s most important reform was the creation of a council of 500 members who were chosen each year by drawing lots. The council prepared business for the general assembly. The new political system provided every citizen of Athens with a chance to help run the city government. All citizens were eligible for the council and for all other offices. Women were not considered citizens and could not vote or hold office. In time, all public officials except generals were chosen annually by drawing lots. Generals were elected. Individuals who were considered to be a threat to the government could be banished for 10 years by a vote of the people.

Era of achievement.

Athens played a leading role in the Greek victories over Persia in the two Persian Wars (490 B.C. and 480-479 B.C.). Athens soon became head of the Delian League, a group of Greek states organized to continue to wage war against Persia. The league quickly developed into an Athenian empire. The period from 477 to 431 B.C. was perhaps the most brilliant in Athenian history. During this time, Athens was led by the great statesman Pericles. He increased Athens’s power in Greece and reformed its government. Pericles also funded many great works of art and architecture. Athens became famous as the literary and artistic center of Greece.

War and decline.

Athens led the empire into the Peloponnesian War (431-404 B.C.) against Sparta and its allies. Sparta won this war and remained the most powerful Greek state until 371 B.C., when it was defeated by Thebes.

Although Athens never regained its political leadership, it remained Greece’s intellectual center. People still came to Athens as a center of culture under Macedonian rule, and later under Roman rule. For hundreds of years, wealthy Roman families sent their sons to Athens to complete their education. However, Athens lost its position as a cultural center in A.D. 529, when the Byzantine emperor Justinian closed the city’s schools of philosophy.

From about 1100 to 1400, during the Middle Ages, Athens declined even further. As the power of Byzantium weakened, various Italian and other European rulers occupied the neglected city. In 1456, Athens fell to the Ottoman Empire. The Islamic Ottomans did little to restore the Christian city to its former glory.

In 1833, after the Greek War of Independence, Athens became the capital of the new kingdom of Greece. The first king, Otto I, or Otho I, and his advisers were German. They used modern Western European ideas—such as public squares and straight streets—in their urban planning designs along the northern and eastern slopes of the Acropolis. The population grew to about 500,000 by the mid-1920’s.

During World War II (1939-1945), Athens was an open city—that is, the Greeks agreed to neither fortify nor defend Athens. They made this agreement in order to protect the city’s historic buildings and works of art against bomb attacks. However, it did nothing to protect Athenians from harsh treatment at the hands of the Germans, who occupied Athens in April 1941. The following winter, thousands of Athenians died of starvation. German troops abandoned the city in 1944.

Renewal.

After the war, archaeologists again began to restore the ruins of ancient Athens. New buildings began to replace structures that had been erected during the reign of Otto I in the mid-1800’s. The historic skyline of three-story buildings is now dotted with modern skyscrapers. In 2004, Athens hosted the Summer Olympic Games.