Antony << AN tuh nee >> , Mark (83?-30 B.C.), a Roman senator and general, was one of Rome’s rulers from 43 B.C. until his death. Antony’s reputation has suffered because of his relationship with Queen Cleopatra of Egypt, and because his rival Octavian defeated him to become Rome’s sole ruler.

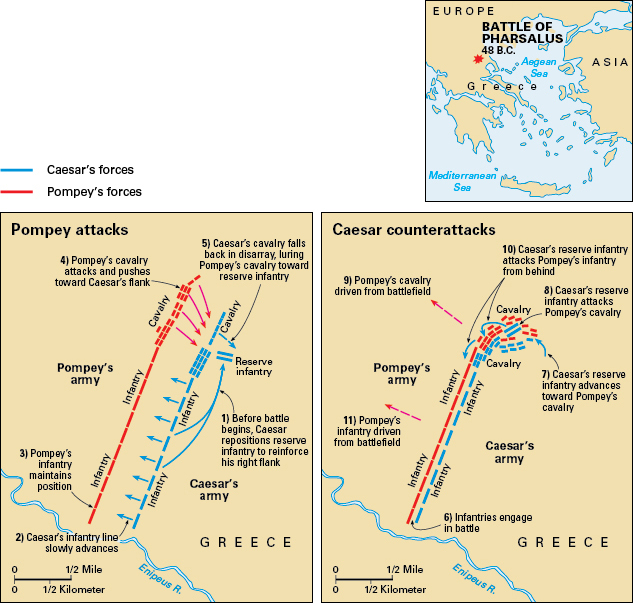

Marcus Antonius, known in English as Mark Antony, was born into a distinguished family with a history of service in the Roman Senate. He served as an officer under Julius Caesar during Caesar’s military campaigns in Gaul. As a tribune of the people (elected representative) in 49 B.C., Antony unsuccessfully advised the Senate against provoking Caesar into civil war. In 48 B.C., he commanded part of the army with which Caesar defeated Pompey, defender of the Roman Republic, at the Battle of Pharsalus.

In 44 B.C., Antony and Caesar were fellow consuls (joint heads of the republic). That year, members of the Senate assassinated Caesar. Afterward, Antony’s efforts to reach a compromise with the Senate failed to satisfy hostile public opinion regarding Caesar’s death. In addition, Antony never imagined that Caesar would make Octavian, his great-nephew, his principal heir. Nor did Antony imagine that Octavian, a weak teenager, would sway public opinion and gather military support against him as effectively as he did. In 43 B.C., after a failed attempt to establish himself as governor of Cisalpine Gaul in northern Italy, Antony agreed to join Octavian and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus in a partnership to rule the Roman world (see Triumvirate). The trio ruthlessly executed opponents and seized their property. Antony took the lead in avenging Caesar’s murder for Octavian. Because of Antony’s generalship, Caesar’s principal assassins—Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus—were defeated in battle at Philippi in 42 B.C.

After the battles at Philippi, Antony oversaw Rome’s eastern territories, and Octavian worked at settling veterans on seized land in Italy. Antony’s wife and brother stirred up resistance to Octavian. Antony might have supported them, but he decided not to turn against Octavian. The gravest threat to the joint rulers’ partnership was the growing seaborne power of Sextus Pompey, the son of Pompey, in the west. Antony dared not refuse Octavian’s pleas for aid, especially for ships, to fight Sextus. In 40 B.C., Antony’s wife died and he married Octavian’s sister Octavia, thus strengthening the two men’s partnership. Octavian finally defeated Sextus Pompey at Naulochus, Sicily, in 36 B.C. with support from both Antony and Lepidus. Then, after Lepidus tried to take control of Sicily and Octavian’s forces, Octavian exiled him from Rome.

In 41 B.C., Antony had sought support from Cleopatra, queen of the wealthy kingdom of Egypt. Antony and Cleopatra’s relationship became personal. Cleopatra bore Antony twins—a girl and a boy—in 40 B.C., and another son in 36 B.C. Antony and Cleopatra seemed to be husband and wife. But Roman law did not recognize marriage with foreigners, and Antony did not divorce Octavia until 32 B.C. Octavia bore him two daughters in 39 and 36 B.C.

A major military campaign by Antony against the kingdom of Parthia in 36 B.C. failed badly. In 34 B.C., however, Antony succeeded in occupying Armenia, and extravagant celebrations were held in Alexandria, Egypt. Octavian, who wished to eliminate Antony, publicized the celebrations as proof that Antony no longer was Roman, but enchanted by Cleopatra’s ambitions. Antony, who still had many friends in Rome, probably wished to continue his partnership with Octavian. But he could not ignore Octavian’s attack, so he called up troops for battle. Octavian defeated Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 B.C. Octavian then laid siege to Alexandria, and Antony soon took his own life.