Argentina << `ahr` juhn TEE nuh >> is the second largest country in area in South America, after Brazil, and the eighth largest in the world. It lies in the southern part of South America and covers an area of 1,073,519 square miles (2,780,400 square kilometers). Chile, Bolivia, Paraguay, Brazil, Uruguay, and the Atlantic Ocean form Argentina’s borders.

Argentina’s landscape varies dramatically throughout the country. The rugged Andes Mountains stretch along the country’s western border. A bare, windswept plateau called Patagonia extends across the south. The Pampas, a fertile, grassy plain, lies near the center of the country. Scrub forests cover much of the north.

Argentina's national anthem

Argentina has a republican form of government. The country is divided into 23 provinces and Buenos Aires Federal District. The city of Buenos Aires, in the federal district, is Argentina’s capital, largest city, main port, and center of business, culture, and trade.

Most Argentines are of Italian or Spanish ancestry. The Indigenous (native) groups that occupied the territory before the arrival of the Spanish today represent only a small portion of the population. Nearly all Argentines speak Spanish and are Roman Catholics.

Argentina is rich in natural resources. Most of its farm exports come from the Pampas region. Beef, corn, soybeans, and wheat are the chief agricultural products. Manufacturing became important in the 1900’s, yet much of the manufacturing involves processing farm products. Argentina’s petroleum industry produces enough oil to meet local demand and also export oil to other countries.

For almost 300 years, Argentina was a Spanish colony. Argentines declared their independence in 1816. Disputes between the capital and the provinces marked most of the 1800’s. Unification and stability in the 1880’s brought prosperity and growth to Argentina. The exporting of meat and grain to Europe made the country wealthy. By the late 1920’s, Argentina had become one of the richest nations in the world.

Today, Argentina no longer ranks among the world’s economic giants. It has an advanced level of industrialization, but economic decline, political instability, social conflict, and violence hampered Argentina’s progress during the last half of the 1900’s.

Government

National government.

Argentina’s Constitution, adopted in 1853, established the country as a democratic republic with independent executive, legislative, and judicial branches. In practice, the executive branch is the strongest. It consists of a president, a vice president, and a Cabinet appointed by the president. The president serves as chief of state and head of government. The people elect the president and vice president to four-year terms. The president and vice president may serve no more than two terms in a row.

The legislature consists of a two-house National Congress with a 72-member Senate and a 257-member Chamber of Deputies. Every two years, citizens elect one-third the number of senators, who serve six-year terms. They also elect about half the number of deputies, who serve four-year terms.

Local government.

Each of Argentina’s 23 provinces has an elected governor and legislature and its own constitution, which resembles the national Constitution. An elected mayor and city council govern Buenos Aires Federal District. Since the mid-1990’s, the federal government has passed reforms to give more responsibilities to local governments.

Politics.

The Justicialist Party (PJ), founded in 1945, historically has been one of Argentina’s largest and strongest political parties. The Radical Civic Union (UCR), founded in 1891, is one of the country’s oldest parties. Traditionally, the PJ has represented labor interests, and the UCR has represented urban middle-class voters. Citizens from 18 to 70 years old are required to vote. Those who are 16 and 17 years old may vote, but voting is optional.

Courts.

The Supreme Court of Justice is Argentina’s highest court. The president appoints the judges of the Supreme Court with the Senate’s approval. The Supreme Court may declare acts of the legislature unconstitutional. The president also appoints judges to the federal courts of appeals upon the recommendation of a Magistrates’ Council. Each province has its own supreme court and lower court system. Provincial governors appoint provincial court judges.

Armed forces.

The three main branches of Argentina’s armed forces are the Air Force, the Army, and the Navy. Other branches include the Coast Guard and the National Gendarmerie (border police). Military service is voluntary.

People

Population.

Some parts of Argentina are heavily populated, while others have few people. For example, about two-fifths of the country‘s population lives in Buenos Aires and its suburbs. Large regions of the country have an unfavorable climate and terrain, and so are sparsely populated. These regions include the high Andes Mountains in the west, the dry Patagonian plateau in the south, and the wooded area called the Chaco in the north.

Ancestry.

Most Argentines are of European ancestry, chiefly Italian and Spanish. Spaniards colonized Argentina in the 1500’s. After Argentina became independent, several waves of European immigration occurred. The largest wave occurred from the late 1800’s to the early 1900’s and was encouraged by a government plan to attract European settlers. The Indigenous population is small compared to that of other Latin American countries and is concentrated mainly in isolated areas in the north and the southwest. Argentina has one of the largest Jewish populations in the Americas. In addition, many people are from Bolivia, Paraguay, and other South American countries.

Language.

The official language of Argentina is Spanish. Many people understand Italian, even if they do not speak it fluently. Argentina’s urban population has become increasingly familiar with English, and English and French are part of the high school curriculum. The main Indigenous languages spoken today are Guaraní, Quechua, and Tehuelche.

Way of life

City life.

Most Argentines, especially middle-class Argentines, live in urban centers, which offer the highest standard of living. Buenos Aires, the capital, is a center of art and culture, as well as the country’s main harbor and a hub of commerce, government, and industry.

Since 1940, industrialization has drawn people to urban centers, where business opportunities, education, and jobs are more readily available than in the countryside. This migration resulted in the development of a large middle-class population in Argentine cities. But the cities are also places of striking contrasts. Wealthy Argentines live in mansions and luxury apartment buildings, while poor workers and a large unemployed population live in suburban slums. Economic problems in the late 1900’s led to the expansion of shantytowns (roughly built areas outside a city).

Many Argentine cities resemble Spanish ones. They are centered around a main square called a plaza. A cathedral and official buildings usually stand near the plaza. Buenos Aires resembles a European capital with attractive parks, balconied apartment buildings, impressive government buildings, and wide boulevards.

Rural life.

As in the cities, there is a large gap between the rich and poor. Wealthy landowners live in elegant homes on huge ranches called estancias, especially on the Pampas and in Patagonia. Some of these homes resemble Spanish houses, with rooms surrounding a patio. Poor rural workers live on small farms with modest houses built of adobe (packed mud) or in huts with adobe walls, dirt floors, and roofs of straw and mud.

In the 1800’s, cowboys called gauchos caught wild cattle and horses on the Pampas for their hides. Many gauchos were mestizos—that is, people with both European and Indigenous ancestry. The romantic figure of the gaucho became part of Argentine folklore. Today, the few remaining gauchos work chiefly as ranch hands on estancias.

Clothing.

Argentines have a reputation for being well dressed. Wealthy city dwellers closely follow international fashion trends. In some rural areas, people wear distinctive clothing. For example, workers on estancias wear at least part of the traditional gaucho costume. These garments include loose trousers tucked into low boots, a poncho (blanket with a slit in the middle for the head), and a wide-brimmed hat. In northwestern Argentina, where Andean culture is strong, clothing sometimes resembles that of Indigenous people in Bolivia and Peru. For example, some people wear derby hats and ponchos.

Food and drink.

Argentina is known for the excellent quality of its beef. The asado (barbecue or roast) is perhaps the most typical Argentine method of cooking meat. An asado may include chicken, pork, prime ribs of beef, sausages, and various glands and organs of animals roasted on an open-air grill called a parrilla or on large spits over a fire. Empanadas, pastries usually filled with ground meat, cheese, vegetables, or other fillings, are a traditional appetizer or snack. High-quality ice cream, pasta, and pizza reflect the influence of Italian cooking. Typical desserts are dulce de leche (a milky caramel) and alfajores (two cookies with a filling, often dulce de leche, sandwiched between them).

In general, Argentines dine at a late hour. Typically, they eat breakfast until 10 a.m., lunch between noon and 2:30 p.m., and dinner after 9 p.m.

The high quality of Argentine wine is recognized worldwide. La Rioja, Mendoza, Salta, and San Juan are notable wine-growing regions. Malbec is a unique Argentine red wine. A tea called mate << MAH tay >> is a popular drink. It is made from the leaves and shoots of the yerba mate plant. People gather and pass a gourd filled with mate around the table, each person sipping through a metal straw. The sharing of mate is an expression of friendship. Yerba mate tea also can be made with tea bags.

Recreation.

Soccer is the most popular sport in Argentina. Other popular sports include basketball, rugby, and automobile and horse racing. The Atlantic coast south of Buenos Aires and the hilly country around Córdoba province are popular vacation spots. The southern Andes is an important tourist destination, attracting hikers, hunters, and skiers.

Argentines observe a number of regional festivals. Northwesterners celebrate Inti Raymi, the Quechua Festival of the Sun, in June. During the festival, they give thanks for the year’s harvest. Two important national holidays are July 9, Independence Day; and May 25, the anniversary of the 1810 revolution, when citizens of Buenos Aires set up an independent government.

Education.

Almost all Argentines aged 15 or older can read and write. The government provides free public elementary and high school education. Argentina also has many privately funded schools that charge tuition. Children from 5 to 14 years old must attend school.

Argentina has about 80 universities. About half of them are free public universities run by the government. The University of Buenos Aires is Argentina’s largest university. Other prominent universities include the Catholic University of Argentina, the National Technological University, and the National University of Córdoba. The country also has a number of public and private technical and vocational schools.

Religion.

More than 90 percent of Argentines are Roman Catholic. However, fewer than 20 percent of urban Catholics regularly practice their religion. Argentina also has small populations of Protestant Christians, Jews, and Muslims.

The arts.

Argentina’s urban centers have many artistic and cultural offerings. European influences are evident in Argentine architecture, motion pictures, fine arts, and music. The Colón Theater, in Buenos Aires, is home to the National Ballet, National Opera, and National Symphony. Buenos Aires also has numerous professional theaters that present plays and musical revues.

Music and dance.

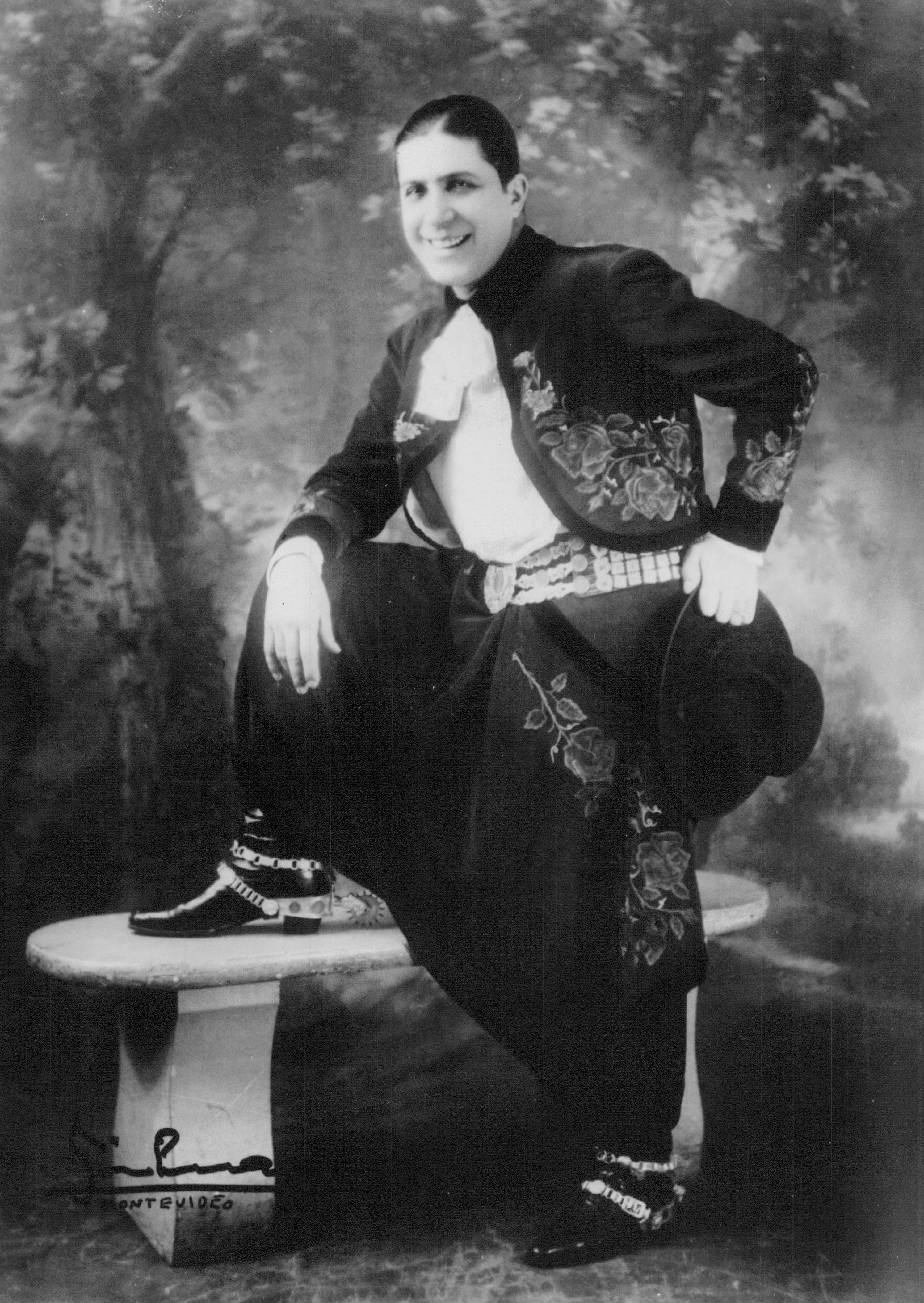

Tango, the national music and dance of Argentina, combines African and European influences. Tango originated in the late 1800’s in the Buenos Aires area. Initially considered a low-class art form, tango eventually spread to such fashionable cities as Paris and New York City, where it gained in popularity and refinement. A sometimes-dramatic dance for couples, tango may be danced socially at events called milongas, or as a performance. It incorporates elegant, intentional walking, intertwining leg movements, and other steps, mostly danced in an embrace.

Tango music may be performed by as few as two musicians or a whole orchestra. A piano, a violin, and a bandoneon, a kind of accordion, are usually included. The lyrics are typically sad and nostalgic. One of the music’s most famous composers was Enrique Santos Discépolo, who wrote many popular tangos from the 1920’s to the 1940’s. Carlos Gardel was an important tango singer in the 1920’s and 1930’s. During the second half of the 1900’s, Astor Piazzolla developed a genre (style) of music known as tango nuevo (new tango). Piazzolla introduced elements of classical and jazz music into the tango. Argentina also has a strong tradition of folk dances and music, including styles known as chacarera, zamba, and malambo.

Literature.

Unlike many former Spanish colonies, Argentina lacks a significant body of colonial literature. About 1776, Alonso Carrió de la Vandera’s travel guide titled The Guide for Blind Wayfarers was published. Filled with details about everyday colonial life, it is a rare and important historical source. Gauchesca poetry, which developed in the mid-1800’s, describes gaucho life and satirizes politics of that time. El gaucho Martín Fierro (1872) and La vuelta de Martín Fierro (The Return of Martín Fierro, 1879), by José Hernández, are the most famous examples of gauchesca poetry. A genre known as criollismo, which originated in the 1800’s and continued into the early 1900’s, describes the lives of rural criollos, people of Spanish descent born in Latin America. Important authors of criollo literature include Benito Lynch and Roberto Jorge Payró.

Historical and political writing characterized much Argentine literature from the middle and late 1800’s. Important writers of this period include Bartolomé Mitre and Domingo Faustino Sarmiento.

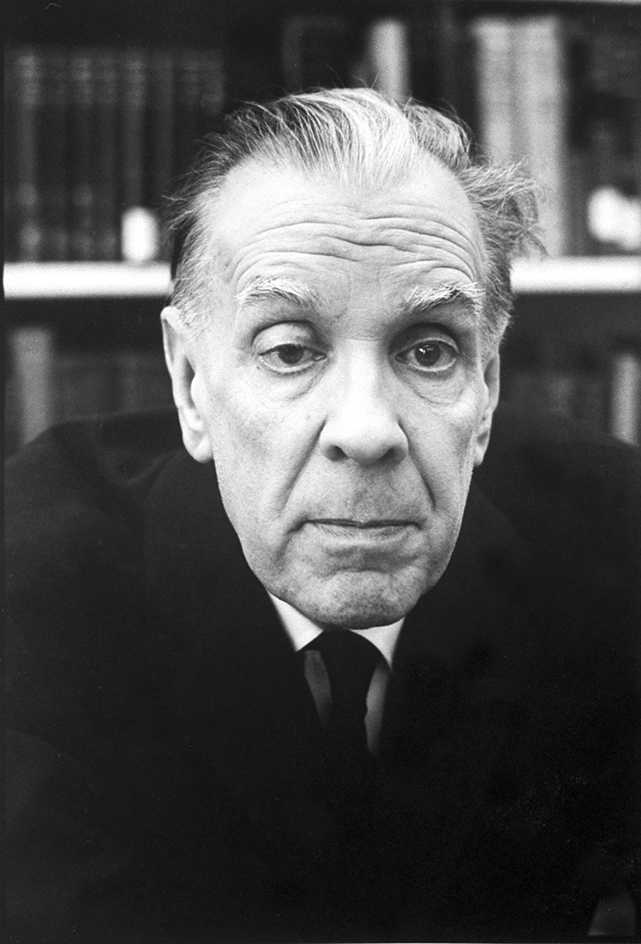

Jorge Luis Borges, an Argentine essayist, poet, and short-story writer of the 1900’s, won broad praise for his brilliant use of language and original observations on the meaning of human existence. Other important authors of the period include Adolfo Bioy Casares, Julio Cortázar, Marta Lynch, Alejandra Pizarnik, Manuel Puig, Ernesto Sábato, Osvaldo Soriano, and Luisa Valenzuela. Important writers of the early 2000’s include the novelists César Aria, Ricardo Piglia, and Andrés Neuman. See Latin American literature.

Painting.

Painting did not develop much before the late 1800’s in Argentina. During the 1800’s, rural life and gaucho legends inspired such Argentine painters as Carlos Morel and Prilidiano Pueyrredón. During the 1900’s, the painter Benito Quinquela Martin portrayed the lives of immigrants and workers in Buenos Aires. Emilio Pettoruti and Alfredo Guttero introduced European avant-garde painting to Argentina in the 1920’s. Since then, various regional and international trends have caught on. Today, Argentina is a major center for Latin American painting. Artists thrive especially in Buenos Aires and the other provincial capitals.

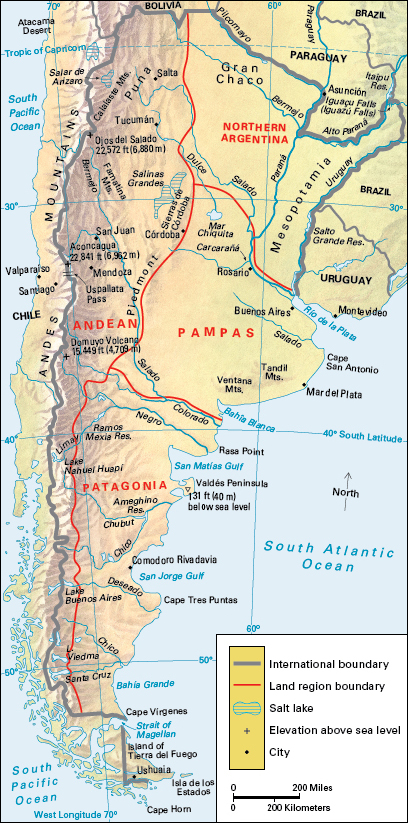

The land

Argentina stretches about 2,300 miles (3,700 kilometers) from north to south. The southernmost tip of Argentina lies only about 600 miles (970 kilometers) from Antarctica. The northernmost part has a nearly tropical climate. Argentina’s landscape includes lofty mountains, vast deserts, fertile plains, and swampy forests.

Argentina can be divided into four main land regions. They are (1) Northern Argentina; (2) the Pampas; (3) the Andean region; and (4) Patagonia.

Northern Argentina

is a lowland plain that lies east of the Andes Mountains and north of the Córdoba Mountains. It consists of two subregions: (1) the Gran Chaco and (2) Mesopotamia.

The Gran Chaco,

also called simply Chaco, lies between the Paraná River on the east and the lower ranges of the Andes on the west. It spreads northward across Paraguay and into Bolivia. Scrub forests cover much of the Chaco, and few people live in the region. The land is dry for most of the year, but heavy rains fall in summer, causing riverbeds to overflow. Farmers plant mostly cotton, soybeans, and sunflowers. They also plant corn, wheat, and other crops after the summer rains.

Quebracho trees grow in the Chaco, and harvesting the trees is an important economic activity. Quebracho means ax breaker in Spanish. The name comes from the tree’s hard wood, which is used to make telephone poles and railroad ties. The tree is also a source of tannin, a chemical used in the leather industry.

Mesopotamia,

like its ancient Middle Eastern namesake, is a fertile region between two rivers. The Argentine Mesopotamia lies between the Paraná and Uruguay rivers. The Paraná River basin is the second largest in South America, after the Amazon basin. Rivers from Bolivia, Brazil, and Paraguay enter the Paraná River. The river originates in Brazil and flows 2,485 miles (3,999 kilometers), emptying into the Atlantic Ocean near Buenos Aires. Along the region’s northern border, the Iguazú (spelled Iguaçu in the Portuguese language) River empties into the Paraná. Near the junction of the two rivers, 275 waterfalls form the spectacular Iguazú Falls.

Mesopotamia has hot, humid summers and cool winters. Rolling, grass-covered plains spread across parts of the region. Farmers graze cattle, sheep, and horses on the plains and grow corn, soybeans, wheat, and some citrus fruits and rice. Swampy forests cover the extreme northeast. The holly tree whose leaves are used to make the tea called mate grows wild in the region.

The Pampas

is a fertile plain that fans out around Buenos Aires. It extends from the Atlantic Ocean to the Andes and covers about a fifth of Argentina. The Pampas has some of the world’s richest topsoil and is Argentina’s most important agricultural region. Fields of corn, soybeans, and wheat cover much of the land. Great herds of cattle graze on the pastures of the Pampas.

The Pampas has about two-thirds of Argentina’s people and most of its urban centers, industries, and transportation facilities. Buenos Aires and Rosario, Argentina’s third largest city, stand at the edge of the Pampas. Beyond these cities, plains stretch as far as the eye can see. Large estates owned by wealthy ranchers cover much of the thinly settled rural Pampas. Westward toward the Andes, the land grows drier.

The Andean Region

is the mountainous western region of Argentina. It consists of two subregions: (1) the Andes Mountains and (2) the Piedmont.

The Andes Mountains

separate Argentina from Chile. Their highest peaks include the tallest mountain in the Western Hemisphere, Aconcagua. It towers 22,841 feet (6,962 meters) above sea level just inside the Argentine border. A small Indigenous population raises sheep in an area of broad plateaus called the Puna in the northern part of the Argentine Andes. In the south, snow-capped peaks, active glaciers, and beautiful lakes attract crowds of vacationers who come to ski and hike.

The Piedmont

is a region of low mountains and desert valleys east of the Andes. Mountain streams provide water for irrigation and make the Piedmont a productive farming area. Farmers grow sugar cane and corn near Tucumán and alfalfa and cotton near Córdoba. Vineyards in Mendoza and San Juan provinces produce grapes for most Argentine wines, which are exported worldwide. Argentina is one of the largest producers of wine in the world. The cities of the Piedmont are some of the oldest Spanish settlements in Argentina.

Patagonia

is a dry, windswept plateau in the south. It occupies more than a quarter of Argentina but has only about 5 percent of the population. Poor soil and scarce rainfall make most of Patagonia unsuitable for crop farming. The extraction of oil and natural gas and sheep ranching are the major economic activities.

Most Patagonians live near the region’s two northern rivers—the Colorado and the Negro. Farmers grow alfalfa, apples, and pears in the river valleys. Wildlife enthusiasts visit Patagonia’s rugged coast to see penguins, sea lions, whales, and other animals.

The island of Tierra del Fuego lies at the southern tip of South America. The Strait of Magellan separates it from the mainland. The island is divided between Argentina and Chile. Ushuaia, one of the southernmost towns in the world, is on Argentina’s part of the island.

Climate

Argentina’s climate is mild. The north has the highest temperatures, and the south, the lowest. Argentina lies south of the equator, and so its seasons are opposite those in the Northern Hemisphere. Summer lasts from late December to late March, and winter, from late June to late September. January temperatures average about 80 °F (27 °C) in the north and about 60 °F (16 °C) in the far south. Average July temperatures range from about 60 °F (16 °C) in the north to about 40 °F (4 °C) in the south.

Rainfall is plentiful in the northeast but decreases toward the west and south. Mesopotamia may receive over 60 inches (150 centimeters) of rain annually, mostly in the summer. Areas of the Piedmont and most of Patagonia get less than 10 inches (25 centimeters), making them deserts or slightly less dry semiarid regions. Nearly two-thirds of Argentina is desert or semiarid.

Ocean currents and winds strongly affect Argentina’s climate. Warm, moist air from the Atlantic can make summers uncomfortably humid in Mesopotamia and the Pampas. Winds from the Pacific lose most of their moisture over the Andes, leaving the Piedmont and Patagonia dry. Winds from both oceans howl continuously over Patagonia. They warm the plateau in winter and cool it in summer. In winter, air from Antarctica sometimes brings cold weather and light snow to Patagonia and the Pampas.

Economy

In the first few decades of the 1900’s, Argentina was one of the richest countries in the world. However, since about 1930, Argentina has had many economic problems. Today, Argentina is no longer one of the world’s economic giants.

Argentina’s economic activity is concentrated mainly in Buenos Aires, Córdoba, and Santa Fe provinces and in the city of Buenos Aires. Traditionally, the economy was based on agricultural exports. Although agricultural exports remain important, service industries and manufacturing now account for about 90 percent of Argentina’s gross domestic product (GDP)—that is, the total value of goods and services produced in a country in one year.

Service industries

account for about two-thirds of Argentina’s GDP. These include financial and insurance services, government services, retail trade, tourism, and transportation. International tourism has gained importance since the early 2000’s. The increase in tourism has helped hotels, restaurants, and other service industries.

Manufacturing

accounts for about 15 percent of Argentina’s GDP. The chief industrial areas include Buenos Aires, Córdoba, and Rosario. The country manufactures automobiles and other transportation equipment, chemicals, machinery, oil, and processed foods.

Mining

accounts for only a small portion of Argentina’s GDP. Petroleum is the country’s chief mineral resource. Patagonia and the Piedmont yield nearly all the oil that Argentina uses, plus a relatively small amount for export. These regions produce natural gas as well. Most of the country’s metal deposits lie in the Andes Mountains and the Piedmont. The deposits include copper, gold, lead, silver, and zinc.

Electric power and utilities.

Plants that burn natural gas are the leading supplier of Argentina’s electric power. Hydroelectric plants supply most of the rest, while nuclear plants provide a small amount of the electric power used by Argentines. In the 1990’s, the government turned over many public utilities to private owners.

Agriculture.

Fertile farmland is Argentina’s most important natural resource. The Pampas and Mesopotamia produce most of Argentina’s leading farm products, such as beef, corn, soybeans, and wheat. Farmers raise sheep, mainly for their wool, in dry areas throughout the country. Argentina is among the world’s leading producers of beef, corn, soybeans, and wool. Much of the country’s soybean harvest is exported to China. Other farm products include apples, citrus fruits, eggs, grapes, milk, potatoes, poultry, sorghum, sugar cane, sunflower seeds, and tea.

Argentine farms vary greatly in size. Huge estates spread over much of the Pampas and make use of modern equipment. In the north, many families farm small plots and raise only enough food to feed themselves. These small farmers often use horse-drawn equipment.

Fishing.

Argentina’s long coastline and continental shelf (submerged land along the coast) provide a great volume and variety of fish. Leading fishing catches include croaker, hake, shrimp, and squid. Fishing crews export most of their catch. China, Italy, Spain, and the United States are among the leading buyers of Argentina’s seafood exports. Since the late 1990’s, laws against overfishing have led to a decrease in Argentina’s commercial catch.

International trade.

Argentina exports more than it imports. Argentina’s main trading partners include Brazil, China, and the United States. Important exports include cars and trucks; corn, soybeans, wheat, and other agricultural products; and petroleum and natural gas. Argentina imports chemicals, machinery, petroleum products, plastics, and transportation equipment.

In 1991, Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay created a trade association known as Mercosur, which stands for Mercado Común del Cono Sur, the Spanish version of the name Southern Common Market. Venezuela later became a member of the group. Other South American countries have become associate members of or signed preferential trade agreements with Mercosur. The Mercosur nations seek to integrate their economies and form one common South American market.

Transportation and communication.

Air routes, highways, and railroads spread out from Buenos Aires, linking most Argentine cities and towns with the capital. The country’s busiest airports are in Buenos Aires. Argentina’s rail network is the largest in South America, but much of it is out of date and inefficient.

Dozens of broadcast television stations operate in Argentina. A majority are privately owned. There are hundreds of radio stations, including private, national, provincial, municipal, and university stations. Argentines also have access to cable and satellite television services. Internet cafes are widely available in major cities. Over 150 newspapers are published in Argentina. Clarín and La Nación, dailies that are published in Buenos Aires, have the largest circulations.

History

Early inhabitants.

Many nomadic tribes roamed the Pampas and Patagonia before Europeans arrived in the 1500’s. Two of the main Indigenous groups in what is now Argentina were the Diaguita, in the northwest, and the Guaraní, in the northeastern and north-central regions of the country. The Diaguita and Guaraní were the first people to settle down and farm in Argentina. They cultivated corn, also called maize, and other crops.

Arrival of the Spanish.

In 1516, a Spanish expedition led by Juan Díaz de Solís landed on the shores of the Río de la Plata and claimed the area for Spain. Solís was seeking a southern passage to the Pacific Ocean. The expedition failed after Indigenous people captured and killed Solís and some of his men. The Indigenous population strongly resisted colonization, and it was not until 1580 that the Spanish securely established the city of Buenos Aires. Spanish colonists who traveled over the Andes Mountains from Peru founded such northwestern settlements as Santiago del Estero and Tucumán.

Settlement and colonial life.

Spanish military campaigns and the introduction of European diseases weakened Indigenous resistance to colonization. Some Indigenous people and Spaniards intermarried, creating a mestizo population of mixed ancestry. Spain, busy exploiting Peru’s gold and silver, largely neglected Argentina, which lacked such riches.

At first, settlements in the northwest grew more rapidly than Buenos Aires and other coastal towns. Spanish colonists forced the Indigenous people to work for them, farming the land and weaving wool into cloth. Soon, these settlements began to supply mining towns in Peru with animals, cloth, and food.

For many years, the Spanish government limited trade through Buenos Aires because they thought the city was vulnerable to attacks by pirates and rival European nations. The city grew slowly, and smuggling became common. In 1680, Portuguese settlers established a trading post across the Río de la Plata from Buenos Aires. Spain then encouraged the city’s growth to protect its colony from Portuguese expansion.

In 1776, Spain combined its American colonies into the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. The viceroyalty included present-day Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay, and parts of Bolivia, Brazil, and Chile. Buenos Aires became the capital of the viceroyalty and a flourishing port.

Road to becoming a nation.

During the early 1800’s, the people of Buenos Aires grew increasingly dissatisfied with Spanish rule. In 1806 and 1807, British troops tried to seize Buenos Aires to establish a foothold in the region for British trade. The city’s residents fought them off without help from Spain, which increased their confidence in gaining freedom from the mother country.

In 1807 and 1808, during the Napoleonic Wars in Europe, France invaded Spain. While the Spanish were busy fighting against Napoleon, Buenos Aires made a move toward independence. On May 25, 1810, citizens of the port city set up their own government to administer the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. But the viceroyal provinces outside Argentina eventually broke away.

Beginning in 1812, the Argentine General José de San Martín led the fight against Spain. At his urging, representatives of the Argentine provinces met at the Congress of Tucumán on July 9, 1816, and officially declared their independence. The new nation became known as the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata. San Martín wanted to expel the Spanish from all of South America. In 1817, he led an expedition into Chile, where he defeated the Spanish. Then, his forces helped Peru win freedom from Spain.

Early independence

in Argentina was marked by a struggle between two political groups—the Unitarists and the Federalists. The Unitarists wanted to set up a strong central government in Buenos Aires. The Federalists represented the large rural landowners of the interior and sought greater local self-rule.

In 1826, a national assembly drew up a constitution for Argentina. The assembly named Bernardino de Rivadavia as the nation’s first president. But Rivadavia resigned in 1827, after failing to create a strong national government. Juan Manuel de Rosas, a landowner from the Pampas, ruled Argentina as a dictator from 1829 to 1852. Rosas created a network of secret police to spy on his enemies and led violent campaigns against the Indigenous people of the Pampas. He quarreled in his dealings with other nations. In 1852, General Justo José de Urquiza led an army revolt that overthrew Rosas.

The Constitution of 1853.

Delegates from all the provinces except Buenos Aires met in Santa Fe in 1852 to organize a national government. They drew up a new constitution based largely on that of the United States. The Constitution, proclaimed in 1853, established a confederation of provinces.

The province of Buenos Aires refused to join the confederation. It prospered as an independent state, aided by good government, high immigration, and European investment. But the confederated provinces fared worse. Urquiza tried to force Buenos Aires to join the confederation. In 1859, he defeated a Buenos Aires army led by General Bartolomé Mitre. But in 1861, Mitre defeated Urquiza in another war. In 1862, Buenos Aires Province agreed to enter the confederation on its own terms. The city of Buenos Aires became the nation’s capital, and Mitre was elected president. In 1860, the country had taken the name Argentina from the Latin word for silver.

With the election of Mitre, Argentina entered a prosperous and stable period that lasted nearly 70 years. Domingo Faustino Sarmiento succeeded Mitre in 1868 and served until 1874. Both men tried to attract European immigrants and investment to speed national growth. Sarmiento also promoted public education.

By the late 1800’s, the Pampas had become the heart of Argentina. Few Indigenous people remained in the region, and thousands of European farmers worked the land. British investment helped build railroads to carry farm products from the Pampas to Buenos Aires for shipment overseas. Between 1880 and 1930, Argentina ranked as one of the world’s wealthiest nations.

Reform movements.

During the late 1800’s, conservative forces dominated Argentine politics, often using fraud to win elections. By that time, a new working-class population had grown up in Argentine cities. In 1889, dissatisfied Argentines formed the Civic Union, an organization that demanded election reform. The Civic Union, which later became the Radical Civic Union, appealed to many immigrants and middle-class business people.

In 1910, Roque Sáenz Peña became president. Although a conservative, Sáenz Peña pushed election reforms through Congress. The reforms, known collectively as the Sáenz Peña Law of 1912, provided for the secret ballot and required every Argentine man 18 years old and older to vote and to register for Army service. The law prevented large landholders from controlling elections and enabled the expanding working and middle classes to participate directly in politics. In 1916, voters elected Radical Civic Union leader Hipólito Yrigoyen president. Marcelo Torcuato de Alvear, also of the Radical Civic Union, succeeded Yrigoyen in 1922.

The first military coup.

Yrigoyen was elected president again in 1928, but he was too ill to govern effectively. The next year, the Great Depression began to shatter the nation’s economy. In 1930, a military coup d’etat (unconstitutional seizure of the government) abruptly ended Yrigoyen’s presidency. The Supreme Court declared the coup lawful, clearing the way for military regimes to rule the country on and off for the next 50 years.

Argentina under Perón.

Following a military coup in 1943, Colonel Juan Domingo Perón rose to power. As head of the Department of Labor and Social Welfare, Perón strengthened Argentina’s unions. Perón’s efforts to improve labor conditions won him the support of urban workers.

Perón was elected president in 1946 and founded the Justicialist Party, also known as the Peronist Party. He helped the working class by promoting union growth and workers’ rights legislation. Perón also promoted industrialization, government control of industry, and Argentine self-determination in foreign affairs. Federal spending rose greatly under Perón. The government taxed farm products to raise money for manufacturing endeavors. As a result, farm production and national income fell.

Perón’s government established strict control over the press. In 1949, he modified the Constitution to increase his powers and allow himself a second term. His second wife, Eva Duarte de Perón, played a key role in developing support for her husband. Known popularly as Evita, she worked to strengthen the voice of Argentine women and the poor until her death in 1952.

Social conflict and economic trouble marked Perón’s second term as president, which began in 1952. He lost the support of the Roman Catholic Church in 1955, after limiting its authority. Perón’s policies resulted in large debts, high inflation, and stagnant productivity levels. In 1955, the Army and Navy revolted against the government. Perón then resigned and went into exile in Spain. But he maintained a base of supporters, especially among labor unions.

Military leaders took control of the government after Perón’s overthrow. In 1956, they reversed Perón’s modifications to the Constitution. In 1958, Arturo Frondizi of the Intransigent Radical Party was elected president. Frondizi cut government spending, limited wage hikes, and introduced other measures to curb inflation and reduce the nation’s debt. Argentines, however, disliked these actions, which called for financial sacrifices.

Army leaders feared that Frondizi would yield to pressure from the Peronistas (supporters of Perón) and restore Perón’s economic policies. They removed Frondizi from office in 1962, and a series of civilian presidents and military dictators ruled until 1972.

During this period, poor management of national finances and military corruption harmed the economy. Public strikes, violence, and antigovernment protests broke out. Military leaders finally allowed Perón’s supporters to return to power in the hope that they could restore order. The people elected Héctor José Campora of the Justicialist Party president in 1973. Perón returned to Argentina later that year, and Campora resigned. Voters then elected Perón president by a wide margin, and his third wife, Isabel, became vice president. After Perón died in 1974, Isabel became the first woman president in the Western Hemisphere.

The 1970’s military dictatorship.

Argentina’s problems increased after Isabel Perón took office. Inflation soared to over 300 percent per year. Many people died in terrorist attacks by right-wing (conservative or traditional) and left-wing (liberal or radical) political extremists. In 1976, military leaders arrested Isabel Perón and took control of the government. The new military dictatorship, led by General Jorge Videla, became known as the Process of National Reorganization, or simply the Process. The Process closed Congress, imposed censorship, and banned labor unions. A paramilitary death squad, unopposed by the state, silenced critics and opponents of the regime. Many experts estimate that the dictatorship imprisoned, tortured, and executed about 30,000 people without trials. Many victims went missing and never were found. They are known as “the disappeared.” The government named the campaign against its enemies the “dirty war.”

Meanwhile, government corruption and the mismanagement of funds caused foreign debt to increase dramatically. The Falklands War of 1982 further strained national finances. Argentina has long claimed the Falkland Islands, which lie about 310 miles (499 kilometers) east of the Strait of Magellan. But since 1833, the United Kingdom has ruled the islands, which Argentines call the Islas Malvinas. In April 1982, Argentine troops seized the Falklands and battled British forces for control of the territory. Argentina surrendered in June but maintained its claim to the islands.

The defeat in the Falklands, public disapproval, and continued economic woes, as well as denunciations of human rights violations by such groups as the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, forced the military government to call free elections. In 1983, voters elected Radical Civic Union leader Raúl Alfonsín president.

The late 1900’s.

President Alfonsín launched a series of measures that aimed to improve the economy, renegotiate the terms of Argentina’s debt, investigate and punish past human rights abuses, and bring the armed forces under civilian control. However, the economy continued to deteriorate, military rebellions occurred, and public confidence in the administration declined.

In 1989, Carlos Saúl Menem of the Justicialist Party won the presidency. Almost immediately after taking office, Menem attempted to stimulate the economy by removing certain restrictions on economic activity. In 1991, in an effort to slow inflation, Menem’s government linked the value of the Argentine peso to that of the U.S. dollar at a rate of one peso to one dollar.

Although Menem’s policies resulted in lower inflation, the return of foreign capital, and economic growth, they had social repercussions. Poverty rose, standards for education and health fell, and the unemployment rate neared 20 percent. In 1994, a constitutional reform shortened the term of the presidency from six to four years and made it possible for Menem to run for reelection.

Menem was reelected in 1995. During his second term, government spending increased and Argentina’s deficit discouraged foreign investment. Domestic interest rates rose, making it more expensive for companies to do business. Many companies closed, resulting in a loss of jobs. Additionally, the transfer of many government-owned businesses to private owners put many more people out of work.

During the late 1990’s, financial crises in other countries and a drop in world prices for farm products contributed to a recession in Argentina that lasted nearly four years. In addition, Argentina’s exports and foreign investment declined. The fixed peso-dollar exchange rate meant that foreign buyers and investors could get more for the same price in other countries.

Fernando de la Rúa was elected president in 1999. De la Rúa was the candidate of a coalition of the Radical Civic Union and other center-left parties. He ran on an anticorruption platform. As president, de la Rúa raised taxes and slashed spending. But these measures impaired economic growth. Fighting within the coalition also prevented the passage of needed reforms. The political situation declined when Vice President Carlos Álvarez resigned over a lack of support for investigation of government corruption.

The early 2000’s.

Argentina experienced an economic crisis in 2001. In December of that year, many people feared that the government would reduce the value of the peso. Large investors withdrew their money from banks and transferred it to accounts overseas. The general population rushed to banks to withdraw their money and convert it to dollars. The government then limited the amount that people could withdraw each week. Violent demonstrations broke out, and more than 25 people were killed. Soon afterward, de la Rúa resigned. In the two weeks following his resignation, two acting presidents and one interim president held office. President Adolfo Rodriguez Saá stopped payment of Argentina’s huge foreign debt.

In January 2002, Congress named Justicialist Senator Eduardo Duhalde president. Duhalde ended the peso’s fixed exchange rate. As a result, the peso fell sharply in value and inflation rose. Poor and middle-class Argentines continued to protest, while the government continued to limit bank withdrawals to keep money in Argentina. Duhalde’s policies eventually stabilized the economy, and the government ended limits on withdrawals.

Néstor Kirchner of the Justicialist Party was elected president in 2003. Kirchner had governed Santa Cruz Province for 12 years. As president, he showed a commitment to reorganizing the police and armed forces, ending corruption, reviewing past human rights abuses, and negotiating terms for repayment of the foreign debt.

Argentine first lady and legislator Cristina Fernández de Kirchner was elected president in 2007, and reelected in 2011. Like her husband, she was a Peronist. Fernández de Kirchner gained popularity for her social welfare programs. But her economic policies eventually led to high inflation, weak economic growth, and a large budget deficit (shortage). Charges of corruption also troubled her presidency.

In 2015, Argentines elected Mauricio Macri of the center-right Cambiemos coalition as president. Macri, a businessman and former mayor of Buenos Aires, failed to improve Argentina’s economy as promised. He lost the 2019 presidential election to Alberto Fernández of the Peronist coalition Frente de Todos. Fernández’s vice presidential running mate was Cristina Fernández de Kirchner.

The COVID-19 pandemic (global outbreak of disease) that began in 2020 greatly impacted Argentina’s public health and its economy. COVID-19 is a respiratory disease caused by a coronavirus. As of early 2023, there had been about 10 million confirmed cases of the coronavirus in Argentina, and more than 130,000 confirmed deaths from COVID-19. Argentina ranked among the nations with the most confirmed cumulative infections and deaths from the disease.

Also in 2023, the far-right libertarian economist Javier Milei was elected president of Argentina. Libertarians favor individual liberty over government control. At the time, the nation was experiencing a severe economic crisis, including extreme inflation and a high rate of poverty.