Artificial limb is a synthetic replacement for an arm or leg lost as the result of injury, disease, or a birth defect. An artificial limb is also called a prosthesis. No artificial limb can perform all the functions of a human limb, but a well-fitted prosthesis can help a person participate in most everyday activities.

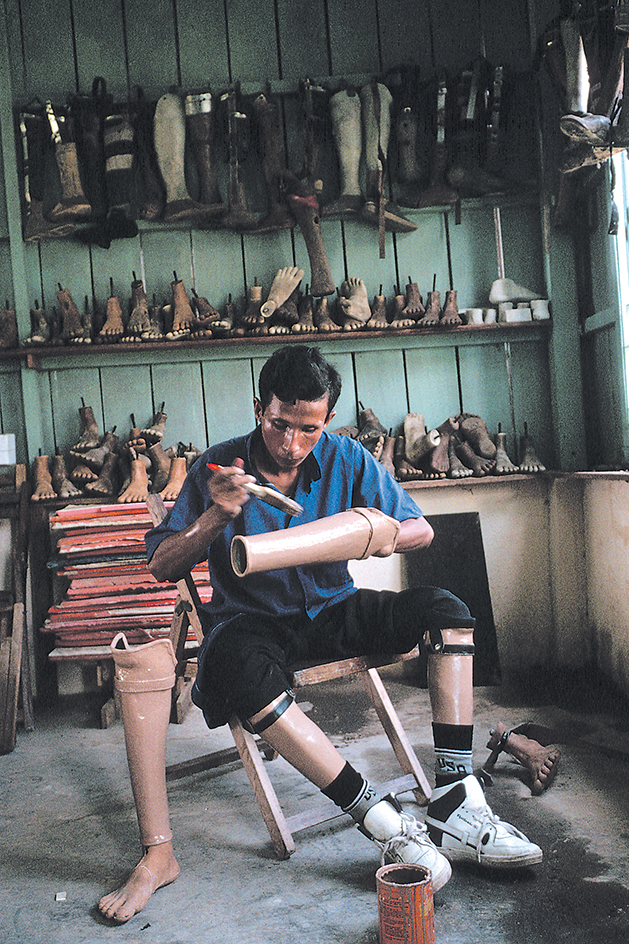

Preparation of an artificial limb.

A prosthesis must be custom made for each patient. In most cases involving an amputated limb, the remaining stump must heal and shrink before it can be fitted with a permanent prosthesis. For several weeks, the stump may be wrapped tightly with elastic bandages to help it shrink to a firm, smooth surface. In some cases, the person wears a rigid plaster cast, to which a temporary prosthesis can be attached. During this time, the person exercises the remaining limb muscles to preserve their strength and movement, and to promote circulation.

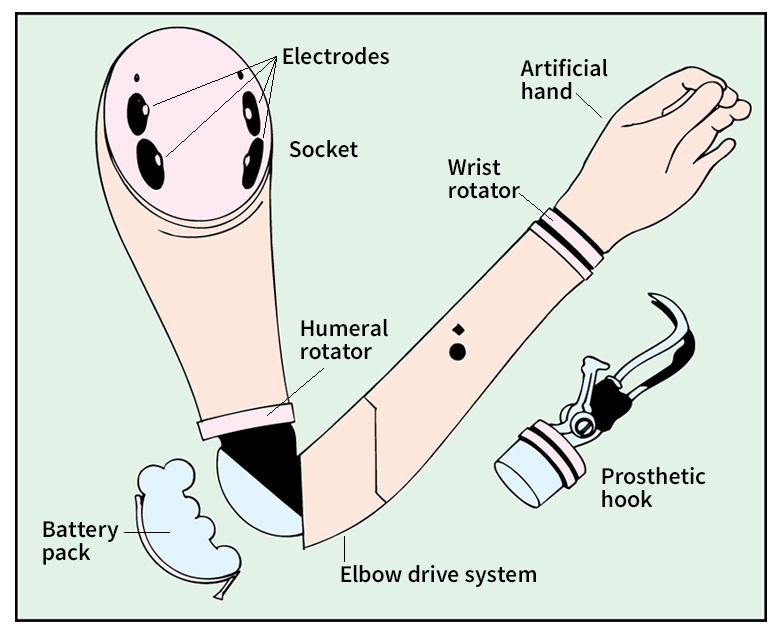

The next step in preparing a prosthesis involves making a plastic socket that will fit over the stump snugly and comfortably. A cast for the socket may be obtained by wrapping the stump with bandages soaked in wet plaster and letting them harden. After the bandages are removed, they form a mold. Liquid plaster poured into this mold provides a model of the stump. A plastic socket is then formed over the model.

An artificial arm or leg is attached to the socket. Materials used in making artificial limbs include plastic, fiberglass, metal, and wood. Light metal supports attached to the socket may contain an artificial joint to replace an elbow or a knee. The prosthesis ends in a substitute hand or foot. Some hand substitutes look like a real hand. But most consist of a pair of metal hooks that act somewhat like tongs. A foot substitute has the same general shape as a normal foot. Most prostheses are attached to the body by straps or by suction.

Control of artificial limbs.

Most artificial arms are controlled by a cable that loops around the opposite shoulder. Movements of that shoulder produce movement in the arm prosthesis. Artificial legs are chiefly controlled by the body’s normal walking movements.

In the early 1960’s, researchers developed a type of prosthesis controlled by myoelectricity—the electric current produced when a muscle contracts. Metal disks inside the socket rest against the skin of the stump. The disks pick up myoelectric impulses, which are then amplified and used to control an electric motor in the prosthesis. In most myoelectric arms, impulses from one muscle bend the arm and those from another muscle straighten it. Similarly, impulses from one arm muscle open a myoelectric hand, and those from another muscle close it. These actions are somewhat like the natural muscle contractions in an arm.