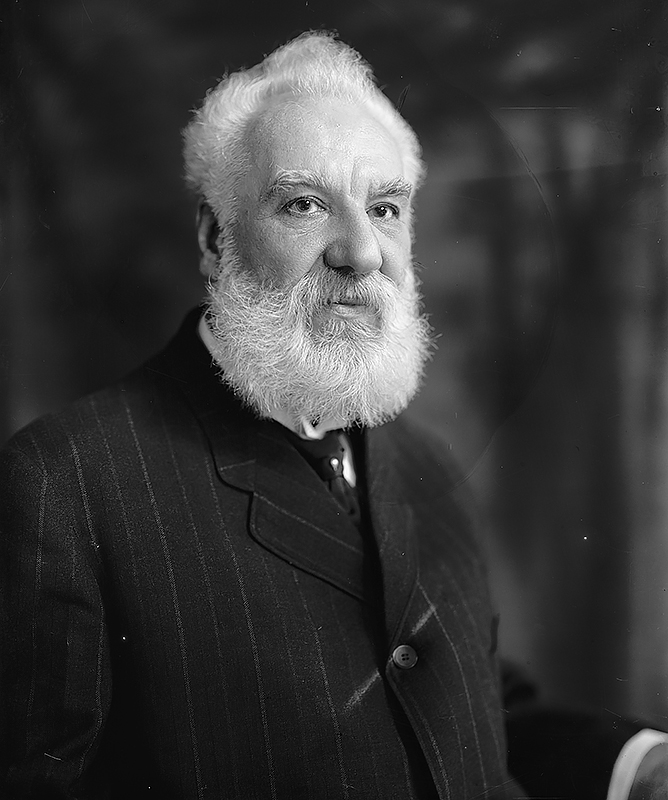

Bell, Alexander Graham (1847-1922), a Scottish-born inventor and educator, is best known for his invention of the telephone. Bell was 27 years old when he worked out the principle of transmitting speech electrically, and was 29 when his basic telephone patent was granted in 1876.

The telegraph had been invented before Bell’s time. Signals, music, and even voicelike sounds had been transmitted electrically by wire. But human speech had never been sent by wire. Many inventors were working to accomplish this, and Bell was the first to succeed.

Bell’s great invention stemmed from his keen interest in the human voice, his basic understanding of acoustics, his goal of developing an improved telegraph system, and his burning desire for fame and fortune. Bell, a teacher of the deaf, once told his family he would rather be remembered as such a teacher than as the inventor of the telephone. But the telephone was of such great importance to the world that Alexander Graham Bell’s name will always be associated with it.

His early life.

Bell’s family and education deeply influenced his career. He was born on March 3, 1847, in Edinburgh, Scotland. His mother, Elisa Grace Symonds, was a portrait painter and an accomplished musician. His father, Alexander Melville Bell, taught deaf-mutes to speak and wrote textbooks on speech. He invented “Visible Speech,” a code of symbols that indicated the position of the throat, tongue, and lips in making sounds. These symbols helped guide the deaf in learning to speak. The boy’s grandfather, Alexander Bell, also specialized in speech. He acted for several years and later gave dramatic readings from Shakespeare.

Young Alexander Graham Bell was named for his grandfather. He adopted his middle name from a friend of the family. His family and close friends called him Graham. He was a talented musician. He played by ear from infancy and received a musical education.

Bell and his two brothers assisted their father in public demonstrations of Visible Speech, beginning in 1862. Bell also enrolled as a student-teacher at Weston House, a boys’ school near Edinburgh, where he taught music and speech in exchange for instruction in other subjects. He became a full-time teacher after studying for a year at the University of Edinburgh. He also studied at the University of London and used Visible Speech to teach a class of deaf children.

In 1866, Bell carried out a series of experiments to determine how vowel sounds are produced. He read a book on acoustics by the German physicist Hermann von Helmholtz, which described experiments in combining the notes of electrically driven tuning forks to make vowel sounds. It gave Bell the idea of “telegraphing” speech, though he had no idea about how to do it. But, this was the start of Bell’s interest in electricity.

Bell took charge of his father’s work while the latter lectured in the United States in 1868. Bell became his father’s partner in London in the following year. He specialized in the anatomy of the vocal apparatus at University College in London at the same time.

Then disaster uprooted the Bell family. Graham’s younger brother had died of tuberculosis, and his elder brother died from the same disease in 1870. The doctors gave warning that Graham, too, was threatened. His father sacrificed his career in London and in August 1870, moved the family to Brantford, Ontario, Canada, where he found during his travels what he considered a healthy climate. Graham soon recovered his health.

The Boston teacher.

Sarah Fuller, principal of a school for the deaf in Boston, asked Melville Bell to show her teachers how to use Visible Speech in teaching deaf pupils to talk. Melville could not go but recommended his son. In 1872, young Bell opened a school for teachers of the deaf in Boston. The following year, he became a professor at Boston University.

Bell’s instruction in Visible Speech and his lively mind won him many friends in Boston. One of these friends was the Boston attorney Gardiner Green Hubbard. Bell met Hubbard through his work with Hubbard’s daughter Mabel, who as a child had been left deaf by scarlet fever. Hubbard was an outspoken critic of Western Union Telegraph Company. When he learned that Bell had been secretly working on improvements to the telegraph, Hubbard immediately offered him financial backing in the hope of outdoing Western Union.

Bell did not attempt to transmit speech electrically when he first began his experiments in 1872. He tried instead to send several telegraph messages over a single wire at the same time—an urgent need of the telegraph industry. In 1874, while visiting his father in Brantford, Bell developed the idea for the telephone. When he returned to Boston, Bell continued his telegraphy experiments, but always with the idea of the telephone in mind.

Bell soon found that he lacked the time and skill to make all the necessary parts for his experiments. At Hubbard’s insistence, he went to an electrical instrument-making shop for help. There, Thomas A. Watson began to assist Bell. The two men became fast friends, and Watson eventually received a share in Bell’s telephone patents as payment for his early work.

The telephone.

During the tedious experiments that followed, Bell reasoned that it would be possible to pick up all the sounds of the human voice on the harmonic telegraph he had developed for sending multiple telegraph messages. Then, on June 2, 1875, while Bell was at one end of the line and Watson worked on the reeds of the telegraph in another room, Bell heard the sound of a plucked reed coming to him over the wire. Quickly he ran to Watson, shouting, “Watson, what did you do then? Don’t change anything.”

After an hour or so of plucking reeds and listening to the sounds, Bell gave his assistant instructions for making a pair of improved instruments. These instruments transmitted recognizable voice sounds, not words. Bell and Watson experimented all summer, and in September 1875, Bell began to write the specifications for his first telephone patent.

The patent was issued on March 7, 1876. Three days later, Bell transmitted human speech for the first time. Bell and Watson, in different rooms, were about to try a new type of transmitter that Bell had briefly described in his patent. Then Watson heard Bell’s voice saying, “Mr. Watson, come here. I want you!” Bell had upset the acid of a battery over his clothes, but he quickly forgot the accident in his excitement over the success of the new transmitter.

Bell demonstrated his telephones at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in June 1876. One of the judges, the Emperor Dom Pedro of Brazil, was impressed by Bell’s instruments. The British scientist Sir William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin) called the telephone “the most wonderful thing in America.”

Bell and Watson gave many successful demonstrations of the telephone, and their work paved the way for commercial telephone service in the United States. The first telephone company, the Bell Telephone Company, came into existence on July 9, 1877. Two days later, Bell married Mabel Hubbard, and they sailed to England to introduce the telephone there. The Bells returned home in 1878 and moved to Washington, D.C.

Bell did not take an active part in the telephone business. But he was frequently called upon to testify in lawsuits brought by men claiming they had invented the telephone earlier, including the American inventors Elisha Gray and Thomas Edison. Several suits reached the Supreme Court of the United States. The court upheld Bell’s rights in all the cases.

His later life.

Bell lived a creative life for more than 45 years after the invention of the telephone. He gave many years of service to the deaf and produced other communication devices.

The French government awarded Bell the Volta Prize of 50,000 francs in 1880 for his invention of the telephone. He used the money to help establish the Volta Laboratory for research, invention, and work for the deaf. There, he and his associates developed the method of making phonograph records on wax disks. The patents for the method were sold in 1886, and Bell used his share of the proceeds to establish the Volta Bureau, a branch of the laboratory, to carry on his work for the deaf. In 1890, Bell founded and financed the American Association to Promote the Teaching of Speech to the Deaf (now called the Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf).

Bell developed an electrical apparatus to locate bullets in the body in a vain effort to save President James Garfield’s life. President Garfield had been shot by an assassin in 1881. Tests on the president were unsuccessful because the doctors failed to remove the steel spring in Garfield’s bed. Bell perfected an electric probe which was used in surgery for several years before the X ray was discovered. Bell also advocated a method of locating icebergs by detecting echoes from them. He worked on methods to make fresh water from vapor in the air for people adrift at sea in open boats. For 30 years, he directed breeding experiments in an attempt to develop a strain of sheep that would bear more than one lamb at a time.

Bell was interested in flying throughout his life. He helped finance American scientist Samuel P. Langley’s experiments with heavier-than-air machines and used his influence in Langley’s behalf. He conducted a long series of experiments with kites capable of lifting a person into the air. These experiments tested the lifting power of plane surfaces at slow speeds. In 1907, Bell helped organize the Aerial Experiment Association, which worked to advance aviation. Bell also contributed to the establishment of Science magazine and helped organize the National Geographic Society.

Alexander Graham Bell became a citizen of the United States in 1882. He spent most of his later life at his estate on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. He worked in his laboratory or sat at his piano playing old Scottish tunes. Bell died Aug. 2, 1922, at his Nova Scotia home.

See also Nova Scotia (table: Places to visit); Hydrofoil (History).