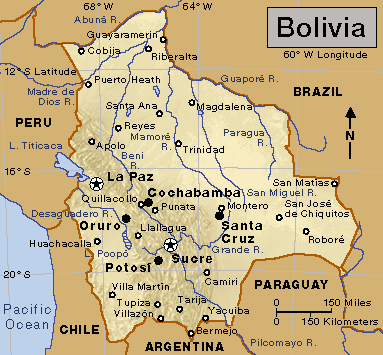

Bolivia << boh LIHV ee uh or buh LIHV ee uh >> is a country near the center of South America. Completely landlocked, the country borders Brazil, Paraguay, Argentina, Chile, and Peru. Bolivia has a rugged landscape, with a number of natural features that make transportation difficult. In western Bolivia, the majestic, snow-capped Andes Mountains surround a high, dry plateau. Tropical rain forests thrive in the northern part of the plain, and grasslands and swamps stretch across much of the east.

Bolivia has two capitals. Sucre, where the Supreme Court meets, is the official capital. However, most government offices are in La Paz, the actual capital. Santa Cruz is Bolivia’s largest city.

Bolivia is rich in natural resources and is a leading producer of natural gas, soybeans, and tin. However, the export of these resources without accompanying industrial development has hampered the country’s economy. As a result, Bolivia has one of the lowest standards of living in the Western Hemisphere. Most Bolivians are poor, and many get only a few years of schooling. About half the country’s workers farm for a living.

Indigenous (native) people lived in what is now Bolivia before Europeans arrived there. During the 1500’s, Spain conquered the area. The Spanish ruled the region until 1825, when Bolivia won its independence. The new country was named for Simón Bolívar. Bolívar, a Venezuelan general, helped Bolivia and several other South American countries win their freedom from Spain. Most Bolivians are of Indigenous ancestry or of mixed Spanish and Indigenous descent.

Government

National government.

Bolivia has had 17 constitutions since it became independent in 1825. Most of the constitutions have called for a freely elected government. However, numerous dictators have ruled Bolivia. Bolivia’s present constitution took effect in 2009.

Bolivia's national anthem

The people of Bolivia elect a president and vice president to five-year terms. The people also elect the members of the two-chamber legislative assembly to five-year terms. The 2009 Constitution recognizes Bolivia’s traditional and Indigenous judicial systems as having equal authority. The highest traditional court is the Supreme Court of Justice.

Local government.

For purposes of local government, Bolivia is divided into departments, provinces, municipalities, and Indigenous territories. A prefect heads the executive body of each department.

Politics.

Bolivia has a number of political parties. Indigenous groups, labor organizations, and the country’s top business people have great influence on national politics. Voting is required for Bolivians who are 18 years of age or older.

The armed forces.

Bolivia has an army; a small navy, which maintains patrol boats on inland waters; and a small air force. All Bolivian men must serve one year in the armed forces.

People

Population and ethnicity.

As Bolivia’s population has grown, it has also become more urban. Since the 1970’s, a majority of Bolivians have lived in cities or towns. The La Paz and Santa Cruz urban areas each have more than 1 million people.

Indigenous people have lived in what is now Bolivia for thousands of years. During the 1500’s, Spain began to colonize the area. Through the years, many Spaniards and Indigenous people intermarried. Today, mestizos (people of mixed European and Indigenous ancestry) make up about 20 percent of the population. About 70 percent of the people are Indigenous, or Indígena, and a small percentage are of European ancestry.

Language.

Bolivia’s 2009 Constitution recognizes Spanish and all Indigenous languages as official languages. It specifically names 36 Indigenous languages, including Aymara, Bésiro (also called Chiquitano), Guaraní, Guarayu, and Quechua. Most people can speak Spanish, and more than half of all Bolivians speak an Indigenous language.

Way of life.

Many Latin American countries have long had strict class systems based on ethnicity. In Bolivia, generations of intermarriage have made it difficult to define the classes according to ethnicity. However, most of the wealthy are of European or mestizo ethnicity, and the majority of the poor are Indigenous.

Wealthy Bolivians, called the elite, form the nation’s smallest social class. The elite speak Spanish and live in city apartments or in elegant Spanish-style houses with patios. Most elite families have had their wealth for generations, and some of them own large amounts of land.

Bolivia’s small middle class includes government officials and doctors, lawyers, and other professionals. The life of the middle class in Bolivia resembles that of the elite but is much less luxurious.

Working-class Bolivians include peddlers, factory workers, and farmers who raise crops chiefly to sell. In highland cities, urban Indigenous Bolivians, called cholos, follow a mixture of Spanish and Indigenous traditions. They speak Spanish in addition to one or more Indigenous languages. The typical cholo house is made of brick and has a tile or metal roof.

Bolivia’s rural population consists largely of campesinos—that is, poor people who farm for a living. Many rural campesinos are Indigenous and speak Indigenous languages. Others are mestizos. Campesinos farm small plots, and most of them raise barely enough food to live on. Many of the women weave textiles or make pottery to earn extra money. Most campesinos live in adobe houses with thatch roofs.

Clothing.

Most wealthy and middle-class Bolivians dress much like the people in the United States and Canada. Many Indigenous people also dress in this style. However, some wear distinctive Indigenous clothing. Such clothing may include striped ponchos for men and colorful shawls and full skirts for women. Many Aymara and Quechua women also wear bowler hats.

Food.

Traditional foods in highland Bolivia include potatoes, corn, and a grain called quinoa. Bolivians often cook chuño, a dried form of potato, in stews or porridges. Some other common dishes include corn-filled pies called humitas and meat turnovers called salteñas. In lowland Bolivia, grilled beef, rice, and many forms of baked corn are common.

Most poor Bolivians have an inadequate diet. Many of them chew the leaves of the coca shrub to relieve hunger and fatigue. Coca leaves contain small amounts of the natural substance cocaine. When chewed, the leaves stimulate the nervous system, as coffee does. Through a refining process, coca leaves may be used to make a powerful illegal drug that is also known as cocaine. However, this drug is not widely consumed in Bolivia. See also Coca; Cocaine.

Religion.

About 90 percent of all Bolivians are Roman Catholics. Most of them take part in church festivals, but few attend Mass regularly. Many Catholics also honor Indigenous religious beliefs. A growing number of Bolivians are Protestants. Other Bolivians follow only Indigenous religious beliefs.

Recreation.

Colorful festivals play an important role in the life of Bolivians. The festivals feature parades, feasts, and elaborate dances. The festival dancers wear brightly colored costumes and masks. Most festivals celebrate national holidays, honor Catholic saints, or express thanks to the Pachamama, the earth goddess of the Indigenous highlanders.

Bolivian folk dance

Soccer is Bolivia’s most popular sport. In the large cities, professional teams play before huge crowds.

Education.

Bolivia provides free elementary and high school education. Children from ages 6 through 13 are expected to attend school. However, many drop out before the age of 13. An especially large number of campesino children leave school to help their families farm the land. Nevertheless, almost all Bolivians 15 years of age or older can read and write.

Bolivia has a number of public and private universities and colleges. The University of St. Francis Xavier in Sucre is one of the oldest universities in South America. It was founded in 1624.

The arts.

For thousands of years, the Indigenous people of Bolivia have made fine jewelry, pottery, and colorful rugs and shawls. The ancient Tiahuanaco culture, which existed near Lake Titicaca from about A.D. 100 to 1200, produced impressive statues and monuments.

The Spanish colonists in Bolivia built many beautiful stone churches during the 1500’s and 1600’s. Indigenous craftworkers, hired by the Spanish, carved bold designs into the outside walls of the churches.

During the 1900’s, social injustice and the everyday activities of Indigenous people provided the themes for many Bolivian writers and artists. For example, Augusto Céspedes examined the mistreatment of Indigenous tin miners in his novel Metal del Diablo (1946). Marina Núñez del Prado won fame for her sculptures depicting Indigenous life.

The land

Bolivia has four major land regions. They are (1) the Andean Highlands, (2) the Yungas, (3) the Valles, and (4) the Oriente (also called the Eastern Lowlands).

The Andean Highlands

cover much of western Bolivia. A high plateau called the Altiplano lies between two craggy ranges of the Andes Mountains. The western range forms part of Bolivia’s western border. The eastern range divides the Altiplano from the rest of the country. About 40 percent of Bolivia’s people live on the Altiplano, many of them in La Paz.

Few trees grow on the Altiplano. The southern section is especially barren. The world’s highest navigable lake, Lake Titicaca, is partly in the northern Altiplano and partly in Peru. The lake lies at an altitude of 12,507 feet (3,812 meters) above sea level. Small farms dot the land near Lake Titicaca.

The Yungas

make up a small region northeast of the Andean Highlands. The region has steep hills and narrow gorges. Subtropical forests thrive on the hillsides. Few people live in the Yungas.

The Valles

lie in south-central Bolivia. The region consists of gently sloping hills and broad valleys. Open grasslands and many farms cover the land. The Valles produce much of the nation’s food.

The Oriente

is a vast lowland plain that spreads across northern and eastern Bolivia. Tropical rain forests flourish in the north. Open grasslands, swamps, and shrubby forests cover much of the rest of the Oriente. Many large farms lie near Santa Cruz. Most of the region has few inhabitants.

Wide, sluggish rivers flow through the Oriente. After a heavy rainfall, numerous rivers overflow their banks and flood the surrounding area. Many of the rivers form part of the Amazon River system.

Climate

The climate in Bolivia varies greatly from region to region. Bolivia lies south of the equator, and so its seasons are opposite those of the Northern Hemisphere. In the Andes Mountains, snow covers the highest peaks the year around. The Altiplano has sparkling clear air and a cool, dry climate. The temperature in the region averages 55 °F (13.1 °C) in January and 40 °F (4.4 °C) in July.

The Yungas have a warm, humid climate. Heavy mists often surround the region’s highest hills. The climate in the Valles is like that of the Yungas, but it is much less humid. The temperature in both the Yungas and the Valles regions averages about 72 °F (22 °C) in January and 52 °F (10.9 °C) in July.

Most of the Oriente has a hot, humid climate. The daily temperature averages 75 °F (24 °C) the year around. However, the temperature drops suddenly when cool, dust-laden winds called the surazos blow northward across the Oriente during the winter months.

The rainy season in most parts of Bolivia lasts from December through February. The Oriente receives the most rain. Light rain falls on the Altiplano, and droughts frequently trouble the region.

Economy

Bolivia has a wealth of natural resources, including minerals, oil and natural gas, pastureland, timber, and fertile soil. However, these resources have not been used effectively to produce economic growth. As a result, Bolivia has one of the poorest economies in Latin America. Many Bolivians live in poverty.

Bolivia’s economy is based on private enterprise. However, since the early 2000’s, the government has played a larger role in the economy by increasing state control over some industries.

Service industries

account for about half of Bolivia’s workers and over half of its gross domestic product (GDP)—that is, the total value of all goods and services produced yearly. Hotels, restaurants, and shops benefit from the hundreds of thousands of tourists who visit Bolivia each year from Argentina, Brazil, Peru, the United States, and other countries. Government agencies and schools are also important service industries. Many poor, urban Bolivians work as housekeepers, street vendors, or small-scale artisans in the informal economy that exists outside of government control and taxation structures.

Agriculture

produces about 15 percent of Bolivia’s GDP and employs about 30 percent of all workers. Farmers on the Altiplano grow corn, potatoes, and quinoa. They raise alpacas, llamas, and sheep for their wool. The Yungas and the Valles regions yield bananas, cacao, coca, coffee, corn, and sugar cane. Bolivia is one of the world’s leading producers of coca. In the Oriente, farmers raise cattle and chickens and grow rice and soybeans.

Manufacturing

accounts for about 10 percent of both Bolivia’s GDP and its employment. Bolivian factories refine minerals, process foods, and make clothing, textiles, and other products. The chief industrial centers are Cochabamba, La Paz, and Santa Cruz.

Mining

is responsible for about 10 percent of Bolivia’s GDP and employs about 1 percent of all workers. Bolivia is one of the world’s leading producers of antimony, lead, silver, tin, tungsten, and zinc. The country also mines copper and gold. Metal deposits lie high in the Andes Mountains. The Oriente yields petroleum and natural gas.

Energy sources.

Petroleum and natural gas supply over half of the energy used in Bolivia. Bolivia is one of South America’s top producers of natural gas, which it exports to Argentina and Brazil. Hydroelectric plants create much of Bolivia’s electricity.

Trade.

Bolivia exports more than it imports. Natural gas is one of Bolivia’s chief legal exports. The illegal export of coca also brings in much money. Other agricultural exports include coffee, lumber, soybeans and soy products, and sugar. Bolivia also exports lead, tin, zinc, and other minerals. Imports include food, heavy machinery, petroleum products, and transportation equipment. Bolivia’s top trading partners include Argentina, Brazil, China, Japan, Peru, and the United States.

Transportation and communication.

Bolivia’s rugged terrain and dense forests have made it difficult to build roads and railroads. The country’s roads are in poor condition, and few people own cars. Most of the travel in cities is by bus. Cochabamba, La Paz, and Santa Cruz have international airports.

Bolivia has numerous newspapers. The country has both state-owned and privately owned radio and television stations.

History

Indigenous people

lived in what is now Bolivia as long as 10,000 years ago. About A.D. 100, a major Indigenous civilization developed in the Tiahuanaco region near Lake Titicaca. The Tiahuanaco (Tiwanaku) people built huge monuments and carved stone statues. Their civilization declined rapidly during the 1200’s. By the late 1300’s, an Indigenous group called the Aymara controlled much of the highlands of western Bolivia. During the 1400’s, the Inca Empire of Peru expanded into Aymara territory. The Inca spread their religion, customs, and language—Quechua—among Bolivia’s Indigenous people. Many other Indigenous peoples lived in the Oriente region of Bolivia.

Colonial rule.

During the 1530’s, Spain conquered the Inca and made Bolivia a Spanish colony called Upper Peru or Charcas. Spanish colonists soon began to settle in Bolivia and established large estates called haciendas. After silver was discovered in the mountains near Potosí in 1545, Spaniards poured into Bolivia by the thousands. Bolivia’s silver became an important source of wealth for Spain.

The Spanish colonists frequently mistreated the Indigenous Bolivians. They forced them to work on the haciendas and in the silver mines. Many Indigenous people died of mistreatment or of diseases brought by the Spaniards. Some Spaniards and Indigenous people intermarried, giving rise to a mestizo population. From time to time, Indigenous people and mestizos rebelled against the Spanish, but they failed to overthrow colonial rule.

Independence.

Spain’s colonies in Latin America gradually became increasingly dissatisfied with Spanish rule. During the early 1800’s, the Venezuelan general Simón Bolívar organized an army to fight for the independence of Spain’s South American colonies.

In 1824, Bolívar sent one of his generals, Antonio José de Sucre, to free Bolivia. In 1825, Sucre’s forces defeated the Spanish, and Bolivia declared its independence. The new nation was named after Bolívar. In 1826, Sucre became the first constitutional president. He governed Bolivia until 1828. In 1829, Andrés Santa Cruz, another of Bolívar’s generals, became president. Under him, Bolivia enjoyed a period of relative prosperity and political stability. Santa Cruz was overthrown in 1839, and dictators ruled Bolivia until the late 1800’s. Most of them cared little about Bolivia’s progress and simply sought to stay in power. Independence did little to change the poor treatment of Indigenous Bolivians.

Territorial losses.

Over time, Bolivia lost more than half its land in wars and treaties with Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, and Peru. In the War of the Pacific (1879-1883), Chile seized Bolivia’s nitrate-rich land along the Pacific Ocean.

In the late 1800’s, the world price of silver increased greatly, and large deposits of tin were discovered in Bolivia. The export of these minerals became highly important to Bolivia’s economy. Political parties representing the interests of the mine owners grew more and more powerful. They controlled Bolivia until the 1930’s and helped the country achieve greater political stability. Bolivia’s presidents during this time devoted much effort to promoting mining and railroad construction.

Bolivia suffered another major territorial loss as a result of the Chaco War. The war broke out in 1932 between Bolivia and Paraguay over ownership of the Gran Chaco, a large lowland plain bordering the two countries. Paraguay defeated Bolivia in 1935. Bolivia gave up most of the disputed land under a settlement arranged in 1938.

The Revolution of 1952.

Great political disorder followed Bolivia’s defeat in the Chaco War. Bolivia had 10 presidents from 1936 to 1952, as one leader after the other seized control of the government. Six presidents were military officers backed by the army. Meanwhile, the tin miners formed unions and held strikes for better working conditions. They supported a political party, called the National Revolutionary Movement, that overthrew the military rulers in 1952. Víctor Paz Estenssoro, an economist and party leader, became president.

Under Paz, the Bolivian government took over the largest tin mines. The government also broke up large estates and gave the land to Indigenous farmers. In 1956, another leader of the Revolutionary Movement, Hernán Siles Zuazo, was elected president. He served until 1960.

Return to military rule.

Paz was reelected in 1960, but a military uprising ousted him in 1964. Through the 1970’s, control of the government changed hands repeatedly, mostly after revolts by rival military officers. The military governments violated civil rights, disallowed opposition to their rule, and imprisoned or killed their enemies. In the late 1960’s, Che Guevara, an Argentine supporter of the Cuban Revolution, tried to start a Communist revolution in Bolivia. Bolivian troops killed him in 1967. See Guevara, Che.

The late 1900’s.

In 1980, Bolivia held an election for a civilian government. But military leaders again seized control of the government before the elected leaders could take office. Then, in 1982, the military allowed a return to civilian government. The Congress elected in 1980 chose Siles Zuazo as president. In presidential elections from 1985 to 2002, no candidate won a majority of the popular vote. As a result, Congress chose the president after each election.

The early 2000’s.

Beginning in 1995, Bolivia’s government sold portions of state-controlled industries, including the airline, oil, gas, and mining industries, to private investors. However, many Bolivians resented what they viewed as foreign firms taking advantage of their country’s natural resources.

Evo Morales, the leader of the left-wing Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) party, was elected president in 2005. He became Bolivia’s first Indigenous president. Morales soon took measures to renationalize the energy industry and to create a new constitution that would give Indigenous people a greater political voice. A new constitution was approved by referendum and took effect in 2009. It lifted a ban on consecutive presidential terms, and Morales was reelected in 2009.

Morales’s social programs helped many poor Bolivians, but some people viewed him as too radical. Morales was reelected in 2014, though the Constitution limited presidents to two consecutive terms. In a 2016 referendum, voters rejected constitutional changes that would have allowed Morales to run for a fourth term. However, the next year, the Constitutional Court ruled that term limits for elected officials violated candidates’ human rights.

Morales ran again for the presidency in 2019 and was declared the winner. Violent protests broke out, and opponents accused the government of meddling with election results. An international group, the Organization of American States, reported evidence of tampering, and Bolivia’s military leadership called upon Morales to step down. Morales resigned, and deputy Senate leader Jeanine Áñez became president, a development that Morales’s supporters considered a coup d’etat—that is, a sudden take-over of government by conspirators. The new government then annulled (canceled) the 2019 election results. Luis Arce of MAS, Morales’s political party, was peacefully elected president in 2020.