Boone, Daniel (1734-1820), is one of the most famous pioneers in United States history. Boone was a sharp-shooting woodsman, a husband and father, a restless trailblazer, and a hard-luck land investor. In the years prior to the American Revolution (1775-1783), Boone led pathfinding missions through the rugged wilderness of the Appalachian Mountains in what is now the eastern United States. He later led groups of settlers to the bountiful frontier land of Kentucky, where he hunted deer for market and surveyed land for future settlement. In doing so, Boone and his companions repeatedly came into conflict with Indigenous (native) Americans (sometimes also known as Native Americans or American Indians). In feats that would contribute to his legend, Boone fought off attacks by Indigenous raiders and made daring rescues of hostages. After being captured by a band of Shawnee, Boone so impressed their leader with his skill and toughness that he was adopted as an honorary member of the tribe.

Boone’s grit and daring gained him wide admiration among his fellow settlers. His adventures in and of themselves, however, did not make Boone a culture hero—that is, a hero of legend. A generation after Boone’s death, American writers and artists fashioned his story into legend. Boone soon came to represent all that many considered great about Americans in an age of revolution, migration, and westward expansion.

Early years.

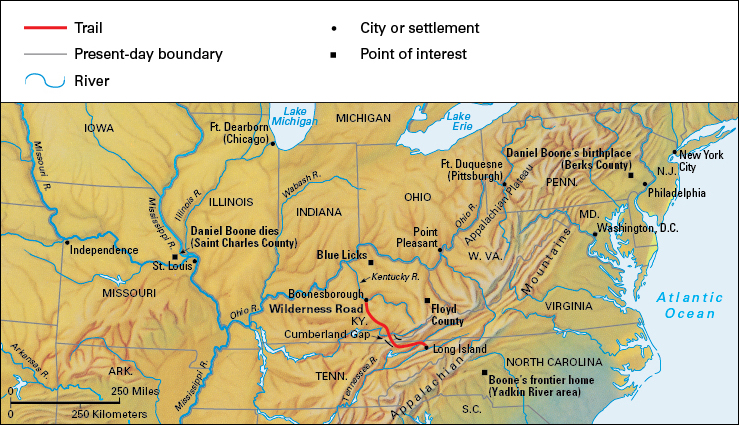

Daniel Boone was born on Nov. 2, 1734, in a log cabin in Berks County, near the present-day city of Reading, Pennsylvania. His parents were hard-working Quakers who had a small farm, a blacksmith shop, and a weaving establishment. There was plenty of work for the young Daniel and his 10 brothers and sisters, who were expected to help with the farm chores.

At about the age of 12, Daniel began to hunt with a rifle his father gave him. He loved the freedom of outdoor life and soon became a skillful woodsman. By practicing with his rifle, he developed a sharp hunter’s eye and helped keep his family well provided with meat.

Like most pioneer children, Daniel had little chance to go to school. He did learn to read, write, and use numbers, but his spelling was poor. It improved little during the rest of his life. The letters he wrote and inscriptions he carved on trees after killing bears show that he was a better hunter than student.

In 1750, Daniel’s father moved the family to the wild frontier country along the Yadkin River in North Carolina. There, Daniel spent much of his time hunting. He traded the animal skins for lead, gunpowder, salt, and other items that the Boones needed.

Tales of a hunter’s paradise.

In 1755, during the French and Indian War (1754-1763), the British general Edward Braddock came to America and led an expedition to seize Fort Duquesne (now Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) from the French, who fought with the aid of Indigenous American allies. Many Indigenous groups in the Ohio Valley saw the British as aggressive occupiers but viewed the French as trusted trading partners.

The British army marched through the Pennsylvania backwoods assisted by American volunteers. Twenty-year-old Daniel Boone was one of the volunteers from North Carolina. He drove a supply wagon.

Among the other wagon drivers was a trader named John Findley (or Finley). Findley had been to the “wonderful” land of Kentucky west of the Appalachian Mountains. His stories were of a hunter’s paradise, a place where the buffaloes were so big that the meadows sank beneath their weight, and where so many turkeys lived that they could not all fly at the same time.

Daniel listened eagerly to these thrilling tales. From Findley he learned of the pass through the mountains called the Cumberland Gap, and of the Warriors’ Path that led to Kentucky.

The French and their Indigenous allies ambushed Braddock’s army. The British troops fled in terror. Boone escaped the ambush with the other wagon drivers. He went home to the Yadkin, but he never forgot Findley’s stories about Kentucky.

Marriage.

One year after his return from Braddock’s expedition, Daniel married Rebecca Bryan, the 17-year-old daughter of his neighbor Joseph Bryan. Rebecca Boone proved to be a sturdy and courageous wife. She bore 10 children—6 sons and 4 daughters—while repeatedly helping Daniel homestead on the frontier.

Whenever too many people settled near the Boone cabin, Daniel wanted to push deeper into the woods where hunting was better. Rebecca disagreed only once. That time, Daniel wanted to move to Florida. He had already been there and purchased some land. But Rebecca objected to leaving her family and friends.

Boone in Kentucky.

In 1769, Boone and his old friend John Findley embarked on a pathfinding expedition that would take them to Kentucky. Their idea was to establish an overland route to the game-rich Ohio Valley, where the two would hunt deer for their skins. Accompanying them were Boone’s brother-in-law John Stuart and three men who kept camp. Boone’s brother Squire joined the group later.

Boone wore a fringed hunting shirt made of black deerskin that almost reached his knees. The darkness of his clothing likely gave him camouflage in the forests. He also wore deerskin leggings and moccasins. He carried a tomahawk and knife in his belt. From leather straps over his shoulder hung a powder horn and a pouch, filled with lead bullets for the long rifle he carried in his hand. His hair was long, tied in a queue (pigtail), and often topped with a black felt hat.

Boone headed west from North Carolina and found the Warriors’ Path. Indigenous people had used this well-worn but narrow trail for hundreds of years. The pioneers followed the Warriors’ Path through the Cumberland Gap into Kentucky. Boone was overjoyed at what he saw. Vast buffalo herds roamed around the salt springs, and deer and turkeys filled the woods. The meadows were ideal for farming. Boone explored and hunted for two years. During that period, he was captured briefly and released by Indigenous people, who viewed white people who hunted for profit as poachers.

Boone returned to North Carolina. In 1773, he led a group of friends and family members into Kentucky, intending to settle there. But during the trip, Indigenous raiders attacked a small group of these settlers. Only one or two survived. Two boys, including Boone’s oldest son, James, were tortured before being killed. The entire party then turned back against Boone’s wishes.

The Wilderness Road.

Richard Henderson, a North Carolina judge, formed the Transylvania Company to establish a new British colony. Boone helped Henderson buy a huge tract of land from the Cherokee people in 1775. Henderson then sent Boone and 30 well-equipped woodsmen to improve and connect some of the trails made by Indigenous travelers and buffalo paths within the region. The resulting route reached into the heart of Kentucky. It became known as the Wilderness Road.

That same year, Boone chose a site by the Kentucky River to build a fort. The site was at the end of Boone’s Trace, a branch of the Wilderness Road south of present-day Lexington. After he built his cabin, Boone brought his family to the fort. Boone’s wife and a daughter, Jemima, were the first white women to see this part of Kentucky. The fort was called Boonesborough. The village was the main settlement in the region then known as Transylvania. Indigenous warriors frequently attacked the pioneer forts in the region.

On July 14, 1776, Jemima Boone and two friends went for a canoe ride. The river’s strong current pushed the canoe toward the opposite shore. Suddenly, a group of Cherokee and Shawnee warriors leaped out from behind the bushes and dragged the three young women to the shore. The screams of the captives had been heard at the fort. Boone assembled two groups to track the warriors and their captives. Two days later, Boone caught up with the kidnappers and directed a surprise attack against them. The three young women were rescued unharmed.

It was clear to Boone and his fellow settlers that they lived in a contested region. American frontiers—places where Indigenous Americans and white settlers competed for land and resources—all too often fostered suspicion and anger rather than understanding and patience. Suspicion and anger, in turn, often led to racism and violence. The violence only worsened after the American Revolution began in 1775. In that conflict, many Indigenous peoples—including those who had captured Jemima Boone—took the side of the British.

Captivity.

In January 1778, Boone and 30 other men headed north to get salt deposits for the settlements in a region known as the Blue Licks. One day while he was out hunting alone, Boone was captured by a band of Shawnee who were allied to the British. For the Shawnee, the war was about protecting their lands from the tide of settlement. Realizing that the Shawnee would attack and kill his fellow salt gatherers if he failed to take action, Boone negotiated their surrender.

The Shawnee—like other woodland peoples of the Ohio Valley and Atlantic seaboard—customarily adopted the women and children they had captured. They seldom adopted men. Adult males could expect to be tortured and executed, or, if they were lucky, to be held for ransom. Though none of Boone’s men were executed, they were forced to undergo a torture called “running the gauntlet.” The gauntlet consisted of two parallel rows of Indigenous men who armed themselves with clubs. Captives had to run between the lines, shielding themselves as best they could from the blows that rained upon them.

After running the gauntlet, captives were typically treated as slaves, though they could later become full members of the tribe. Far from enslaving Boone, however, Chief Blackfish soon adopted him as his own son. He gave Boone the name Shel-tow-ee (Big Turtle). The Shawnee plucked all of Boone’s hair from his head, except for a scalp lock (tuft of hair) on the crown. They took him to the river to “wash away his white blood.” He was now a Shawnee. Sixteen of Boone’s men were likewise adopted. The Shawnee sold the other captives to the British at Detroit.

Escape and battle.

Although Boone seemed to enjoy life as one of the Shawnee, he secretly waited for a chance to escape. When he learned that Blackfish was planning to attack Boonesborough, he advised Blackfish that the fort was too strong to take. He argued that Blackfish should wait until some of the fort’s defenders departed. Before Blackfish could launch his raid, however, Boone ran away. Being nimble in the woods and toughened by hunting, he was able to travel 160 miles (260 kilometers) to Boonesborough in just four days.

Upon his arrival, Boone convinced half the fort’s defenders to raid a nearby Shawnee town rather than strengthen the fort. His idea was to seize horses and beaver pelts. The raid, however, was a failure. The men returned to Boonesborough only hours before Blackfish surrounded the fort with his 400 men. Boone knew that the settlers were hopelessly outnumbered. He told his fellow defenders that he was willing to fight but had no objection to surrender, assuming Blackfish would guarantee safe passage to the British fort at Detroit.

Boone then led a party outside the fort to attempt negotiations—or at least pretend to do so as a way to delay the attack. After a lengthy parley, it seems, the Boonesborough men agreed to recognize British authority rather than fight for the United States. Just as the two sides sought to confirm their agreement, a fight broke out. The two sides fired on each other as the settlers retreated to the fort. Blackfish’s men then lay siege to Boonesborough. They tossed torches against the stockade walls and tried to tunnel underneath them. After nine days, Blackfish gave up. The defenders had prevailed, thanks in part to nightly rains that kept the wooden fortress too damp to burn down.

Boone’s troubles were not over, however. Two of his fellow defenders—both officers in the American military—charged that Boone, while held captive by the Shawnee, had consorted (improperly associated) with the British. Boone, they said, had promised to hand over Boonesborough. Furthermore, they insisted, he had shown his traitorous intentions again after the Shawnee attackers surrounded the fort. Boone’s statement that he had been willing to surrender even before the fighting began seemed to confirm their charges.

In a sense, the charges against Boone were true. Like many frontier settlers, Boone seems to have had only weak loyalty to the cause of the American Revolution. His primary concern was to protect his family and his fellow settlers, even if that meant negotiations and surrender. Boone defended himself from the charges by claiming that he had only sought to trick the British and the Shawnee, not endorse their cause. After a court-martial (military trial) in 1779, Boone was exonerated (declared innocent).

Land trouble.

After the Revolution, Boone served as a state legislator and worked as a tavern keeper. He also owned seven enslaved people. By the mid-1780’s, Boone was one of Kentucky’s richest men in terms of land. He had claimed almost 100,000 acres (40,500 hectares). But he faced trouble that for once he could not defeat. Lawyers sued him because he had failed to get title (legal right) to the land he claimed. By 1798, he had lost nearly all his land and was deeply in debt.

Boone in Missouri.

In 1799, Boone went west again. He led a group of settlers into Missouri at the invitation of the Spanish governor who controlled the territory. During the journey, someone asked Boone why he left Kentucky. Boone’s famous reply was, “Too many people! Too crowded! Too crowded! I want more elbow-room.”

The Spanish awarded Boone a grant of about 850 acres (345 hectares) of land in Missouri. He was also appointed syndic (judge) of the Femme Osage district, about 60 miles (100 kilometers) west of St. Louis. He received more land after he brought in 100 new families.

Boone had Spanish title but not American title to his land. When the territory became part of the United States under the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, Boone lost all his land again. The U.S. Congress reissued the original grant of 850 acres in 1814 for his services in opening the West. But Boone had to sell the land to pay off debts.

During his later years, Boone continued to hunt and explore the West. When his eyesight became too weak for shooting, he set traps for game. He died on Sept. 26, 1820, at the home of his son Nathan. In 1845, the people of Missouri agreed to have the remains of Boone and his wife moved to Frankfort, Kentucky, the state capital. The Missourians wanted the famous pioneer brought home to his “hunter’s paradise.”

Boone’s legacy.

The first full biography of Boone was published in 1833. By 1868, it had been reprinted 14 times, making it perhaps the most widely read American biography of the century. Its popularity, in turn, led other writers to publish their own Boone biographies. They praised him for “self-possession”—that is, his coolness when faced with danger. Artists, too, painted and sculpted heroic images of Boone.

In the popular imagination, Boone became an “American Native”—a white man who seemed every bit as indigenous as Native Americans were. He seemed to symbolize the greatness of European Americans who were fast settling the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys, then moving onward to the Far West.

Boone’s story, then, can be seen as the story of American cultural history, not solely the story of only the man himself. It is a story of migration and expansion, rugged individualists, and hopeful pioneers. It is also a story about the displacement of Indigenous Americans, who were pushed west, then confined to reservations.