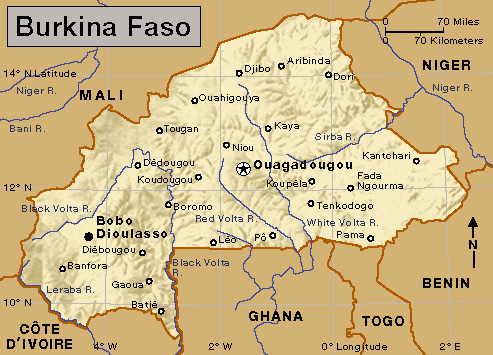

Burkina Faso << bur KEE nuh FAH soh >> is a country in western Africa. It lies about 600 miles (970 kilometers) east of the Atlantic Ocean in the western “bulge” of Africa. The country was formerly called Upper Volta. In 1984, its name was changed to Burkina Faso. Burkina is a name for the country’s people. It means honest people. Burkina Faso means land of the honest people.

Landlocked Burkina Faso is one of Africa’s poorest and least developed countries. It consists mostly of wooded, grassy plains atop a plateau. The dry, rocky landscape turns green for only a few months each year. Because the country lacks rich soil and mineral deposits, many of its people have only the bare necessities of life. Most people make their living by farming and raising cattle. France governed Burkina Faso for 63 years before it became independent in 1960. Ouagadougou is the capital and largest city.

Government.

In 2022, Burkina Faso’s military seized control of the government and suspended the country’s Constitution. Under the Constitution, a president was Burkina Faso’s most powerful official. The people elected the president to a five-year term. A Council of Ministers helped the president carry out government operations. A legislature called the National Assembly made the laws. The people elected the Assembly members to five-year terms.

Burkina Faso is divided into 45 provinces for purposes of local government. A high commissioner leads the government of each province.

People.

Most of the people of Burkina Faso belong to one of two main cultural groups, the Voltaic and the Mande. The Voltaic group includes the Mossi, the Bobo, the Gurunsi, and the Lobi peoples. The Mossi make up about half of the country’s population. For over 800 years, they have had a kingdom with a central government headed by the Moro Naba (Mossi chief). A Moro Naba still holds court in Ouagadougou, the principal Mossi city. Most of the Mossi are farmers who live in the central and eastern parts of Burkina Faso. The typical Mossi family lives in a yiri, a group of mud-brick houses surrounding a small court. The families keep sheep and goats in the court.

The Bobo, the Gurunsi, and the Lobi each make up less than 10 percent of the population. The Bobo live in the southwest around Bobo Dioulasso. They live in large villages where they build castlelike houses with clay brick walls and straw roofs. The Gurunsi, who live around Koudougou, have adopted modern changes more readily than the Mossi have. The Lobi live in the Gaoua region. They have long been hunters and farmers, but now they work as migrant laborers in and around the cities.

The Mande group includes the Boussance, Marka, Samo, and Senufo peoples. These peoples are branches of Mande groups living in the neighboring countries of Mali, Guinea, and northern Côte d’Ivoire. Burkina Faso also has several hundred thousand Fulani and Tuareg nomads. These people travel between grazing areas in the northern part of Burkina Faso with their goats, sheep, and other livestock. A few Hausa merchants live in urban areas.

Many people of Burkina Faso practice local traditional religions. However, Islam and Christian religions are growing rapidly. About 60 percent of the people are Muslims, and about 25 percent are Christians.

Less than half of Burkina Faso’s adults can read and write. The University of Ouagadougou is the main institution of higher education.

Land.

Burkina Faso is a vast inland plateau that varies from 650 to 2,300 feet (198 to 701 meters) or more above sea level. Wooded grassland covers most of the country, but there is a swampy region in the southeast and wooded hills lie in the west.

Rivers have cut many valleys in the plateau. The Black Volta, Red Volta, and White Volta rivers flow south to Ghana’s Lake Volta. Rivers in the east flow into the Niger River. But most of Burkina Faso is dry and rocky. The country’s poor, thin soil does not hold water. The 30 to 45 inches (76 to 114 centimeters) of rain that most of Burkina Faso gets each year quickly runs off.

Burkina Faso’s climate is cool and dry from November to February, and hot and dry from March to April. From May to October, it is wet and hot. The average temperatures for most of the year in Burkina Faso range from 68 to 95 °F (20 to 35 °C).

Economy.

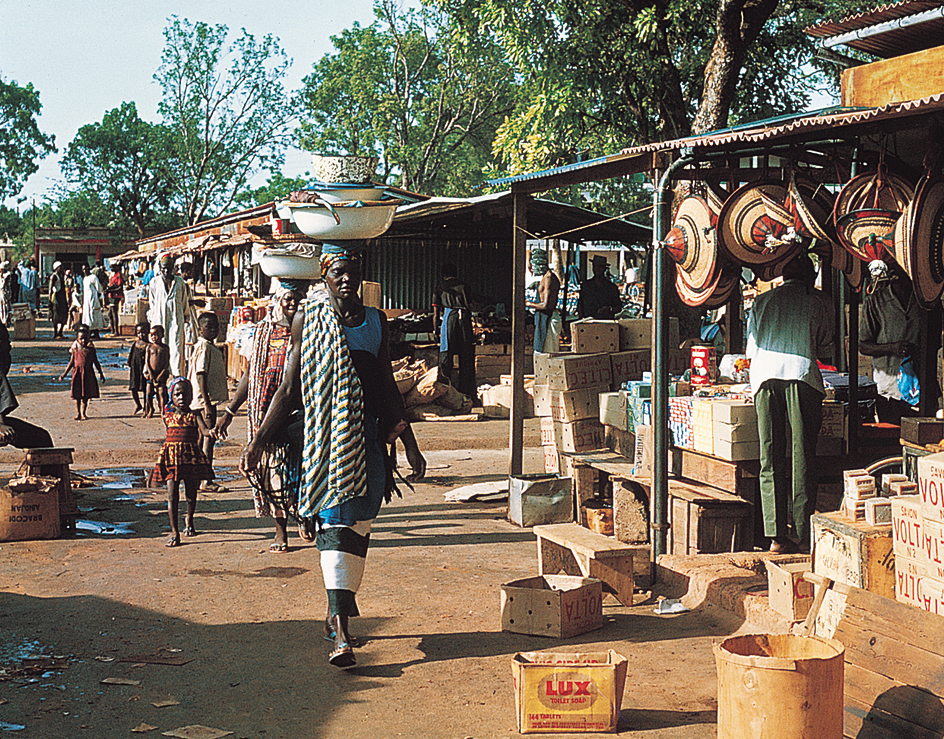

Burkina Faso is one of Africa’s poorest and least developed countries. Most of its people depend on subsistence farming. The country has millions of cattle, chickens, goats, hogs, and sheep. Most farmland in the country is in river valleys. Farmers raise such crops as corn, millet, rice, and sorghum. The main cash crops include cotton, peanuts, and shea nuts (seeds that contain a fat used to make soap).

Manufacturing is centered on processing cotton and other agricultural products. Gold mining is important to the country’s economy. Many of Burkina Faso’s young men go to Côte d’Ivoire or other countries to work. The money they send home is an important part of Burkina Faso’s income.

Burkina Faso imports more than it exports. It imports food, machinery, petroleum, and vehicles. The country’s main exports are cotton and other agricultural products and gold. China, Côte d’Ivoire, France, Ghana, and Switzerland are among Burkina Faso’s leading trade partners.

History.

The Mossi have a long history. The Mossi of the Yatenga region, northwest of Ouagadougou, set up a well-organized kingdom in the 1300’s. They moved their capital to Ouagadougou in the mid-1400’s. They had a strong military force and fought off powerful Songhai invaders from what is now Mali in the 1500’s. But the attacks weakened the Mossi kingdom, and it began to decline.

Most Europeans did not learn of the Mossi kingdom until the 1800’s. France conquered Ouagadougou in September 1896. In January 1897, the Moro Naba signed a treaty placing the Mossi kingdom under French protection. In 1919, France created the colony of Upper Volta in what is now Burkina Faso, then dismantled it in 1932 and divided it among three other French colonies—Côte d’Ivoire, French Sudan (now Mali), and Niger. France re-created Upper Volta with its pre-1932 boundaries in 1947.

Upper Volta’s independence movement began after movements in neighboring French colonies. Many political parties were formed to represent the Mossi, Bobo, and other peoples. The African Democratic Rally Party, led by Daniel Ouezzin Coulibaly, became the largest. In 1957, Ouezzin Coulibaly became head of Upper Volta’s government. In 1958, Upper Volta became a self-governing state within the French Community, an organization that linked France and its overseas territories. Ouezzin Coulibaly died in 1958, and Maurice Yaméogo took his place. In 1959, Upper Volta joined Dahomey (now Benin), Côte d’Ivoire, and Niger in the Council of the Entente, a group formed to solve the region’s economic and social problems.

On Aug. 5, 1960, Upper Volta became an independent republic with Yaméogo as president and head of the African Democratic Rally Party, soon the country’s only legal political party. By January 1966, the people had become dissatisfied with Yaméogo’s rule. A general strike by labor union workers protested wage reductions proposed by the government and governmental dishonesty. During the strike, the army took control of the government. General Sangoule Lamizana became head of the military government.

In 1970, voters approved a new constitution and elected a legislature. Lamizana remained as president. In 1971, he appointed a civilian prime minister. But in 1974, Lamizana suspended the Constitution, abolished the office of prime minister, and dissolved the legislature. He then ruled with the assistance of a cabinet that included many military officers. A new constitution, adopted in 1977, restored civilian rule. In 1978, Lamizana was elected president. In 1980, Colonel Saye Zerbo overthrew Lamizana in a coup d’etat (revolt against the government). In 1983, Captain Thomas Sankara came to power in a coup. In 1987, Sankara was overthrown and assassinated, and Captain Blaise Compaoré became president.

Burkina Faso adopted a new constitution in June 1991, and a multiparty presidential election was held in December of that year. But opposition parties refused to participate in the election because they claimed election reform was needed first. Compaoré won by a huge margin. A few days after the election, Burkina Faso’s most important opposition leader was assassinated.

Elections for a new legislative body, the Assembly of People’s Deputies, were held in May 1992. Compaoré’s party, the Organization for Popular Democracy-Labor Movement (ODP-MT), won most of the seats.

In 1996, the ODP-MT merged with a number of smaller parties to form the Congress for Democracy and Progress (CDP). The CDP won legislative elections in 1997, 2002, 2007, and 2012. In 1998, Compaoré was reelected president. In 2005, he was reelected to a third term as president, though a new constitution limited the number of presidential terms to two. The Constitutional Court decided that the term limit did not apply to Compaoré because it went into effect after he was already in office. Compaoré was reelected again in 2010. In 2013, the government made progress toward creating a second legislative house, to be called the Senate. Opposition leaders feared Compaoré would use the Senate to amend the Constitution and allow him to further extend his presidency. Massive protests against the Senate led the government to delay its implementation.

In 2014, the government considered amending the Constitution to allow Compaoré to run for another presidential term. The issue set off violent protests. Compaoré stepped down from the presidency and fled to neighboring Côte d’Ivoire. The army took power and created a transitional government to prepare for new elections. In 2015, voters elected former Compaoré ally Roch Marc Christian Kaboré to the presidency. Kaboré was reelected in 2020.

Beginning in the 2010’s, countries of the Sahel region of west Africa, including Burkina Faso, suffered violence from rival armed groups battling for control of territory. In Burkina Faso, Islamist insurgent (rebel) groups and local militias have attacked villages and killed many civilians, especially in the north. In 2020, five countries together known as the G5—Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger—formed a joint military force. Mali later withdrew from the force. The force began working with France to combat increased attacks by Islamist insurgents in the Sahel region. Despite this cooperation, people of Burkina Faso continued to suffer violent attacks and killings by extremist groups.

In January 2022, Burkina Faso’s military overthrew President Kaboré. The military took control of the government, dissolved the country’s legislature, and suspended Burkina Faso’s Constitution. Violence has continued to plague the country, including attacks by government-allied militias against the Fulani people. In early 2023, Burkina Faso expelled French troops and ended an agreement with France that provided for military cooperation against insurgents.