Caesar, << SEE zuhr, >> Julius (100-44 B.C.), was a Roman general, politician, and writer. He became the most important person in Rome when he defeated his former son-in-law, Pompey the Great, in a bitter civil war. After being made dictator for life, Caesar was assassinated by his political opponents.

Background and early life.

Gaius Julius Caesar was born in Rome into a famous patrician (aristocratic) family. His family claimed to be descended from the goddess Venus by way of her son Aeneas and his son Ascanius (also called Iulus). Caesar’s aunt was married to the great Roman general and popular leader Gaius Marius. At the age of 17, Caesar married Cornelia, the daughter of Lucius Cornelius Cinna, an ally of Marius. After a brief period of military service in Asia, Caesar went to Greece to study philosophy and oratory. In 73 B.C., Caesar was made a pontifex (Roman priest) and returned to Rome. There, he was elected a military tribune (military leader). In 68 B.C., Caesar was elected a quaestor (financial official), the first step on the Roman ladder of political offices. Caesar’s aunt Julia died the same year. He made a speech in her honor in which he also showed his allegiance to the people of Rome. Caesar and Cornelia had a daughter, Julia. Cornelia died around the same time.

Political career.

In 60 B.C., Caesar allied himself with Marcus Licinius Crassus and Gnaeus Pompey. Crassus was a man of enormous wealth and political ambition. Pompey was a great military leader and the idol of the people. Their alliance is called the First Triumvirate. Through the use of violence and bribery, Caesar was elected a consul, the highest political office in Rome, in 59 B.C. As consul, Caesar promoted the triumvirate’s agenda. To cement the alliance, Pompey married Caesar’s daughter, Julia. In 59 B.C., Caesar married Calpurnia, daughter of Lucius Piso of Rome. Caesar recognized that he needed military victories to gain greater fame. He accepted a five-year command as proconsul (governor) of Cisalpine Gaul, Illyricum, and Transalpine Gaul, provinces north of Italy.

Campaigns in Gaul.

In 58 B.C., Caesar began a campaign to conquer Gaul (an area that is now mainly France). In nine years, to 51 B.C., Caesar conquered the Gallic tribes from the Rhine River to the Pyrenees mountains. He also crossed the Rhine to intimidate the Germans. In addition, he took forces to Britain twice but did not establish any permanent settlement there.

During Caesar’s time in Gaul, the triumvirate began to deteriorate. Caesar’s daughter, Julia, died in 54 B.C. Crassus was killed in the Battle of Carrhae in 53 B.C. Great public celebrations were held in Rome in thanksgiving for Caesar’s victories, but not everyone rejoiced over his conquests. Pompey became alarmed at Caesar’s success. Pompey’s growing suspicions of Caesar led him into an alliance with the senatorial classes. By 52 B.C., Caesar’s enemies were plotting against him. They prevented him from standing for consul while he was absent from Rome.

Civil war.

In 49 B.C., some senators ordered Caesar to give up his army. Caesar had no intention of surrendering his army and leaving himself defenseless. He led 5,000 soldiers across the Rubicon, a stream that separated his provinces from Italy. After this hostile act, there was no turning back. Caesar had provoked, or been provoked into, a civil war. As Caesar hurried south, he met little opposition. Pompey’s troops surrendered, forcing Pompey to flee east. The senators who had ordered Caesar to give up his army fled with Pompey.

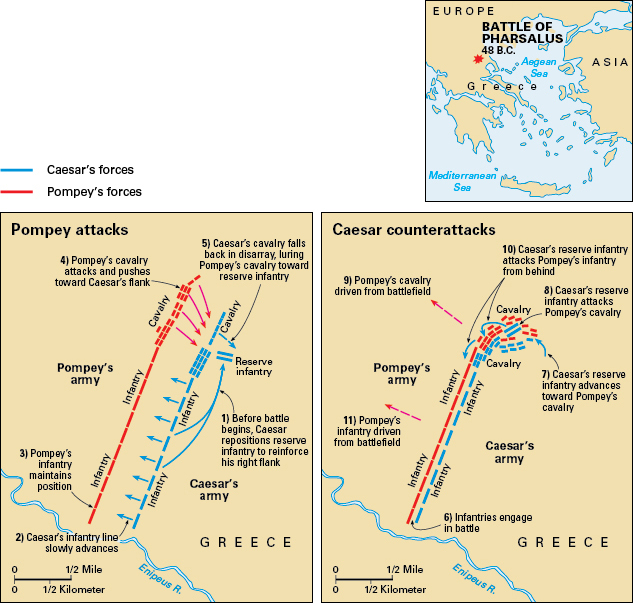

Within 60 days, Caesar was master of Italy and had himself appointed dictator and consul. But it took him nearly five years to complete the conquest of Pompey and his followers. Caesar defeated Pompey’s forces at Pharsalus (now Farsala), Greece, in 48 B.C. Pompey escaped to Egypt. But he was killed as he stepped off the boat that took him there, on the orders of the young pharaoh Ptolemy XIII. Caesar followed Pompey to Egypt. There he met Cleopatra, with whom he had a love affair. They had a son named Caesarion. Caesar made Cleopatra ruler of Egypt.

Caesar then spent time in Syria and Asia Minor, where he defeated kings loyal to Pompey. In 47 B.C., he defeated King Pharnaces II of Pontus at Zela, in what is now Turkey. After this victory, Caesar sent this famous dispatch to the Senate: “Veni, vidi, vici” (“I came, I saw, I conquered”). Caesar defeated Pompey’s followers at the Battle of Thapsus in Africa in 46 B.C. In Rome, Caesar was named dictator for another 10 years. Caesar’s final battle occurred in 45 B.C. in Munda, Spain, where he defeated Pompey’s two sons.

Final days.

Caesar had now become undisputed master of the Roman world. He pardoned the followers of Pompey, and the people honored Caesar for his leadership and triumphs. At the start of 44 B.C., he was made dictator for life and given honors normally given only to gods.

Some Romans suspected that Caesar intended to make himself king. Mark Antony offered Caesar the crown in public at a religious festival. Caesar refused it, but some people remained suspicious of him. Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius, both pardoned by Caesar after the Battle of Pharsalus, led a group of senators in a plot to kill Caesar. On March 15 (the Ides of March), 44 B.C., the senators stabbed Caesar to death as he entered a Senate meeting at the Theater of Pompey.

Reforms and legacy.

Caesar wisely used the power he had won, and he made many important reforms. He tried to control dishonest practices in the Roman and provincial governments. He reformed the calendar to create a 365-day year with one extra day every four years. He established a plan for reorganizing city government in Italy. He tried to reconcile his opponents by appointing them to public office. He also granted Roman citizenship to many people in the provinces.

Caesar improved the situation of Rome’s poorest people. He established colonies, notably at Carthage and Corinth. He continued to distribute free grain but reduced the number of people eligible for it. He is said to have planned many other reforms, such as the founding of public libraries and the construction of a canal across the Isthmus of Corinth.

Caesar was regarded as one of the foremost orators of his time. He also was highly regarded as a writer. He composed a series of Commentaries on the Gallic War and another work about the civil war of 49 B.C. These works won praise for their clear, elegant style.

Caesar proved he was capable of governing Rome and its vast possessions. He may be regarded as the most talented Roman of his generation. He saw ways of solving some of the republic’s problems. Yet many of his actions offended Roman traditionalists. Caesar treated the Senate as a mere advisory council, and the senators resented such disrespect. He also offended many Romans by assuming the office of dictator. He was the first Roman ruler to hold absolute power. In addition, Caesar was the first to demonstrate that a new solution was required to resolve the civil strife and infighting of the elite classes that had affected the last generation of the republic. But he was too impatient. Rome required a stronger diplomat, who came along in the form of Caesar’s adopted son, Octavian. Octavian became Rome’s first emperor, Augustus.