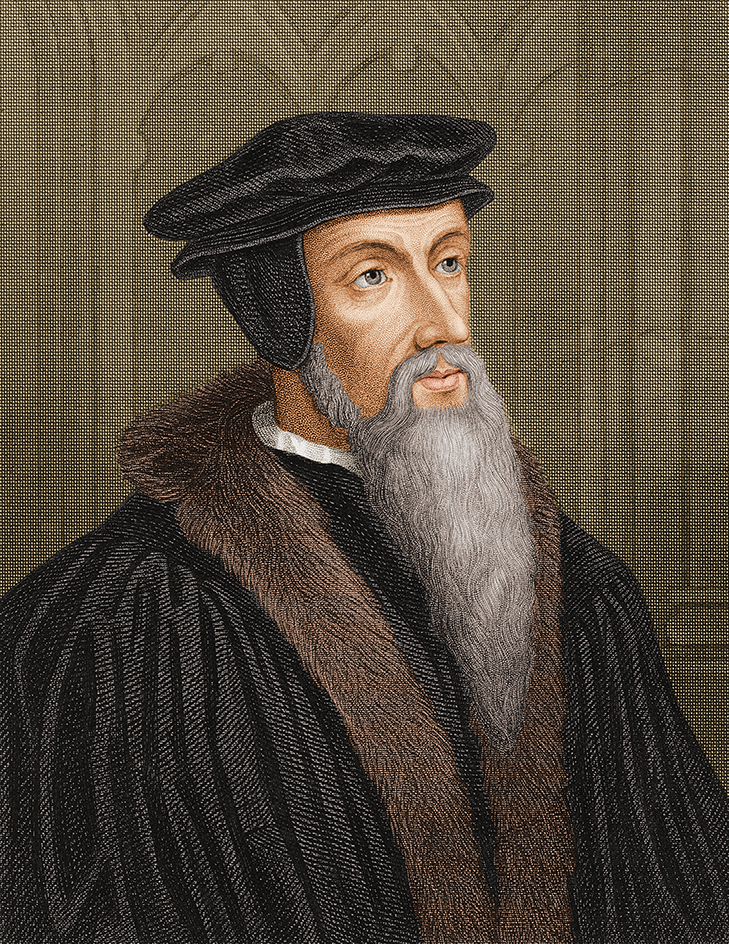

Calvin, John (1509-1564), was one of the chief leaders of the Reformation, a religious movement that led to Protestantism. Calvin’s brilliant mind, powerful preaching, many books and large correspondence, and capacity for organization and administration made him a dominant figure of the Reformation. He was especially influential in Switzerland, England, Scotland, and colonial North America.

His life.

Calvin was born in Noyon, France, near Compiegne, on July 10, 1509. His father was a lawyer for the Roman Catholic Church. Calvin was educated in Paris, Orleans, and Bourges. After his father’s death in 1531, he studied Greek and Latin at the University of Paris. Thus, Calvin’s education reflected the influence of the liberal and humanistic Renaissance. Unlike several other Reformation leaders, Calvin was probably never ordained a priest.

By 1533, Calvin had declared himself a Protestant. In 1534, he settled in Basel, Switzerland. There, he published the first edition of his Institutes of the Christian Religion (1536). This book achieved immediate recognition for Calvin, and he expanded it throughout his life. The book sets forth Calvin’s basic ideas on religion and is a masterpiece of Reformation thought.

In 1536, Calvin was persuaded to become a leader of Geneva’s first group of Protestant pastors. In 1538, Geneva’s leaders reacted against the strict doctrines of the Protestant pastors, and Calvin and several other clergymen were banished. Later that year, Calvin became pastor of a French refugee Protestant church in Strasbourg, Germany. He was deeply influenced by the older German Protestant leaders of Strasbourg, especially Martin Bucer. Calvin adapted Bucer’s ideas on church government and worship.

Geneva lacked able religious and political leadership. The Geneva city council begged Calvin to return, and he did so in 1541. From then until his death on May 27, 1564, Calvin was the dominant personality in Geneva.

Calvinism.

From its beginning in 1517, the Reformation brought religious and political opposition from the Catholic church and from civil rulers. By 1546, many Protestants in Germany, Switzerland, and France were insisting that the people—not just kings and bishops—should share in political and religious policymaking. This idea influenced Calvin and his followers in France, England, Scotland, and the Netherlands. Calvin’s French followers were called Huguenots. In England, Calvin’s influence was especially strong among the reformers known as Puritans.

The Calvinists developed political theories that supported constitutional government, representative government, the right of people to change their government, and the separation of civil government from church government. Calvinists of the 1500’s intended these ideas to apply only to the aristocracy. But during the 1600’s, more democratic concepts arose, especially in England and later in colonial America.

Calvin agreed with other early Reformation leaders on such basic religious teachings as the superiority of faith over good works, the Bible as the basis of all Christian teachings, and the universal priesthood of all believers. According to the concept of universal priesthood, all believers were considered priests. Catholic priests were set apart from lay people by their power to perform the sacraments.

Calvin also declared that people were saved solely by the grace of God, and that only people called the Elect would be saved. Only God knew for sure who the Elect were. For Calvin, however, those who believed in his teachings and were not public sinners were accepted as church members in Geneva. Calvin expanded the idea that Christianity was intended to reform all of society. He lectured and wrote on politics, social problems, and international issues as part of Christian responsibility.

Many of Calvin’s ideas were controversial, but no other reformer did so much to force people to think about Christian social ethics. From this ethical concern and Bucer’s ideas, Calvin developed the pattern of church government that today is called presbyterian. Calvin organized the church government distinct from civil government, though the two governments often cooperated with each other. He was the first Protestant leader in Europe to gain partial church independence from the state.