Chile << CHIHL ee or CHEE lay >> is a long, narrow country on South America’s west coast. It is more than 10 times as long as it is wide and stretches about 2,650 miles (4,265 kilometers) from Peru in the north to the southern tip of the continent. Chile’s name probably comes from chilli, an Indigenous (native) word meaning where the land ends.

Chile is a land of great variety. The Atacama Desert in the north is one of the driest places in the world, but parts of the south are among the rainiest. The towering Andes Mountains form Chile’s eastern boundary, and low mountains rise along the country’s Pacific coast. A series of fertile river basins called the Central Valley lies between the mountain ranges in central Chile. The landscape of southern Chile is breathtaking. There are snow-capped volcanoes, thick forests, and huge glaciers. Many rocky, windswept islands dot the rugged shore.

Most Chileans are of mixed Spanish and Indigenous ancestry. Many others are of unmixed European descent. Indigenous people—descendants of Chile’s original inhabitants—form another group. Nearly all Chileans speak Spanish, the nation’s official language, and a majority of the people are Roman Catholics.

Santiago is Chile’s capital and largest city. It lies in the Central Valley, where the great majority of Chile’s people live. The Central Valley also has the country’s other largest cities, its major factories, and its best farmland.

Since about 1900, poor, rural Chileans have poured into the cities in search of a better life. But there are not enough jobs in the cities. Also, many rural Chileans lack the skills needed for available city jobs. As a result, Chile’s large urban areas have had such problems as poverty, unemployment, pollution, and inadequate housing.

Chile is the world’s leading copper-producing nation. Its economy depends on copper exports. Farms in the Central Valley produce plentiful crops, but most fruit grown there is exported. Chile imports much of its food, manufactured goods, and petroleum.

For nearly 300 years, Chile was a Spanish colony. It gained independence in 1818. In 1833, a long period of constitutional rule began in Chile. Except for a few civil wars in the 1800’s and a dictatorship from 1927 to 1931, the country became increasingly democratic. In 1973, military leaders overthrew the civilian government and set up a dictatorship. But in 1990, a democratically elected civilian government was reestablished.

Government

National government.

Chile is a republic. The president serves as head of state. The president is elected by the people to a four-year term and may not be elected for two consecutive terms. A Cabinet appointed by the president helps carry out government functions.

The Chilean legislature, called the National Congress, consists of two houses—the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. Voters elect 155 deputies and 50 senators to terms of four and eight years, respectively.

Loading the player...Chile's national anthem

Local government.

Chile is divided into 15 regions, including the Metropolitan Region, which contains the capital, Santiago. The regions are further divided into provinces. The provinces are divided into hundreds of municipalities. The national government appoints the regional and provincial administrators. The people elect municipal officials to four-year terms.

Courts.

The Supreme Court, Chile’s highest court, consists of 21 judges appointed by the president. It reviews decisions made by lower courts. A separate body called the Constitutional Tribunal rules on the constitutionality of laws and reviews constitutional amendments. The court system also includes courts of appeal, criminal courts, and district courts.

Armed forces.

Chile has an army, navy, and air force. Men and women between the ages of 18 and 45 can volunteer to serve in the armed forces. Men who do not volunteer are eligible to be drafted at age 18. Both men and women attend Chile’s military academies.

People

Population.

Chile’s population is unevenly distributed. Relatively few people live in the Northern Desert region or in the rugged Andes. Southern Chile, with its many islands and thick forests, is also thinly populated. Most Chileans live in the Central Valley, which has a pleasant climate and rich soil.

Ancestry.

Indigenous people lived in what is now Chile long before Spaniards arrived in the 1500’s. Over the years, many Spanish settlers and Indigenous people intermarried. Their descendants are called mestizos. Today, mestizos and people of unmixed European descent, chiefly Spanish, make up nearly 90 percent of the population. A small percentage of Chileans are of unmixed Indigenous ancestry.

About 1 1/2 million Mapuche people form the largest Indigenous group in Chile. The Spanish called the Mapuche Araucanians after a tree native to southern Chile. The Mapuche fought the Spaniards and their descendants for about 350 years. Today, most Indigenous Chileans live in urban areas, but many of the Mapuche still live in rural areas of southern Chile. The Indigenous population of Chile also includes small groups of Atacameños, Quechua, and Aymara people, most of whom live in the north.

Social classes in Chile are based chiefly on wealth, not ancestry. But nearly all members of the small, rich upper class have some European ancestry. Mestizos make up most of the middle class. The lower class consists mainly of poor mestizos and most of Chile’s Indigenous people.

Language.

Nearly all Chileans speak Spanish, the country’s official language. Indigenous languages also remain important in Indigenous communities.

Way of life

City life.

In Santiago and other major Chilean cities, modern steel and glass skyscrapers rise in busy commercial districts. The cities also have many Spanish-style buildings with red tile roofs and patios. Monuments and impressive public buildings border treelined streets. The cities are also known for their parks, gardens, and large plazas (public squares).

Wealthy city dwellers in Chile live in luxurious high-rise apartment buildings or spacious houses with fenced-in lawns and gardens. The well-to-do include business executives, industrialists, and owners of country estates who prefer to live in the city. Many middle-class city dwellers work in business or industry or have government or professional jobs. They live in apartments or comfortable single-family houses. Working-class city dwellers include salesclerks, factory workers, domestic servants, and other Chileans with low-paying jobs. Many of them live in run-down buildings in older neighborhoods. Some build their own homes out of discarded materials.

Since about 1900, poor rural Chileans have come to the cities—especially Santiago—to find work. By the 1930’s, Chile had become a mostly urban society. However, there have been too few jobs and inadequate housing for the poor migrants. During much of the 1900’s, many of them resided in slums called callampas (mushrooms) because, like mushrooms, the slums seemed to spring up overnight. Since the 1970’s, urban reforms have pushed the poor to the outskirts of Santiago and other cities. Government-subsidized programs in these areas have steadily replaced the substandard dwellings of the callampas with adequate housing and public services. In addition, economic prosperity has brought steady improvement to transportation systems and other parts of urban infrastructure.

Rural life.

Most of the people who live in the rural areas of Chile are small-scale farmers or temporary workers, or are engaged in commerce or services. Before the 1960’s, large estates called fundos filled the countryside. Farmworkers called inquilinos lived on the fundos. In exchange for their labor, the inquilinos received a small wage, housing, and a plot of land on which to grow food. Inquilinos’ wives and children often worked as unpaid servants in the fundo household.

In the 1960’s, a government land reform program began to break up the fundos. In addition, many rural workers invaded the large estates and demanded land. Chile’s governments often sided with the workers. But the reforms were stopped when the military took over the government in 1973. The military returned some lands to the large estate owners, kept some lands as a public reserve, and left the rest with small-scale farmers. Many rural poor were left with nothing. Those who had farms often lacked the credit or facilities needed to succeed. As a result, rural people continued to migrate to the cities.

Clothing.

Chileans dress much as people do in the United States and other Western countries. For rodeos and other special events, Chilean cowboys, called huasos, wear big flat-topped hats, ponchos, colorful sashes, fringed leather leggings, and boots with spurs. The clothing of the Mapuche women of south-central Chile includes brightly colored shawls and heavy silver jewelry.

Food and drink.

Most Chileans have enough to eat, though many poor people lack a well-balanced diet. The Chilean diet is based on bread, beans, and potatoes. Most people also regularly eat at least a little meat in addition to many kinds of fish and shellfish. Meat and vegetables are often combined in stews or thick soups. Chileans enjoy a number of traditional dishes. Cazuela de ave is a hearty soup consisting of chicken, rice, and vegetables. Pastel de choclo, a baked corn casserole, is made of grated corn, minced meat, raisins, and onions. Other favorite dishes include a fish chowder called paila marina and empanadas—pastry turnovers stuffed with meat or seafood, eggs, vegetables, and fruit.

Coffee and tea, including an herb tea called agüita, are popular beverages. Domestically produced wines also are popular.

Recreation.

Movies are a popular form of recreation in Chilean cities. In Santiago and other major cities, concerts, plays, ballets, and operas also attract large audiences. Rural Chileans enjoy family outings and visits with friends and neighbors. Chileans also celebrate various religious holidays with parades and festivals.

Chile’s long Pacific coastline is dotted with scenic beaches. Vacationers from many countries flock to the luxurious coastal resort of Viña del Mar during the warmer months of December through March. South-central Chile’s Lake Country offers fishing, boating, and hiking. Portillo and other ski resorts in the Andes attract wealthy Chileans and foreigners.

Soccer is Chile’s most popular spectator sport by far. Fans crowd the stadiums to watch games and cheer their favorite teams. Chileans also enjoy such sports as horse racing, basketball, and tennis.

Religion.

Spanish colonists brought the Roman Catholic religion to Chile. Today, a majority of Chileans are Catholics. The Catholic Church operates many schools in Chile, and church leaders have actively promoted political and social reforms.

The number of Protestants in Chile is growing. Protestant groups include Baptists, Lutherans, Methodists, and an increasing number of Pentecostal churches.

Education.

Nearly all Chileans aged 15 and older can read and write. Chile provides free public elementary education, and children must attend eight years of elementary school. Many elementary school graduates do not go to high school because they must work to help support their families. Chile has both public and private high schools. Some private schools receive government funding. The University of Chile, in Santiago, is the country’s oldest and largest institution of higher learning. In addition to universities, postsecondary schools include professional institutes and technical centers.

The arts.

Chile’s greatest achievements in the arts have been in literature. La Araucana, written by Alonso de Ercilla y Zúñiga in the late 1500’s, ranks as one of the great epic poems in Latin American literature. It tells of the Mapuche people’s fight against the Spanish conquerors of Chile. In 1945, the Chilean poet Gabriela Mistral became the first Latin American writer to win the Nobel Prize in literature. Her works express great sympathy for the needy. One of her students, Pablo Neruda, won the 1971 Nobel Prize in literature. His poems express the joys, dreams, struggles, and frustrations of ordinary Latin Americans. Ariel Dorfman gained international recognition for his fiction and nonfiction works that explore the terrors of political dictatorship. Other famous Chilean authors include Isabel Allende and Roberto Bolaño.

The land

Chile lies along South America’s Pacific coast. It extends 2,650 miles (4,265 kilometers) from north to south but is only 265 miles (427 kilometers) wide at its widest point. A low range of mountains rises along the coast. The lofty Andes Mountains form the country’s eastern boundary with Bolivia and Argentina. Chile lies along a major earthquake belt and is frequently struck by earthquakes and tsunamis (groups of huge, destructive ocean waves).

Chile can be divided into three land regions. They are, from north to south: (1) the Northern Desert, (2) the Central Valley, and (3) the Archipelago. In addition, Chile owns a number of small islands in the Pacific Ocean.

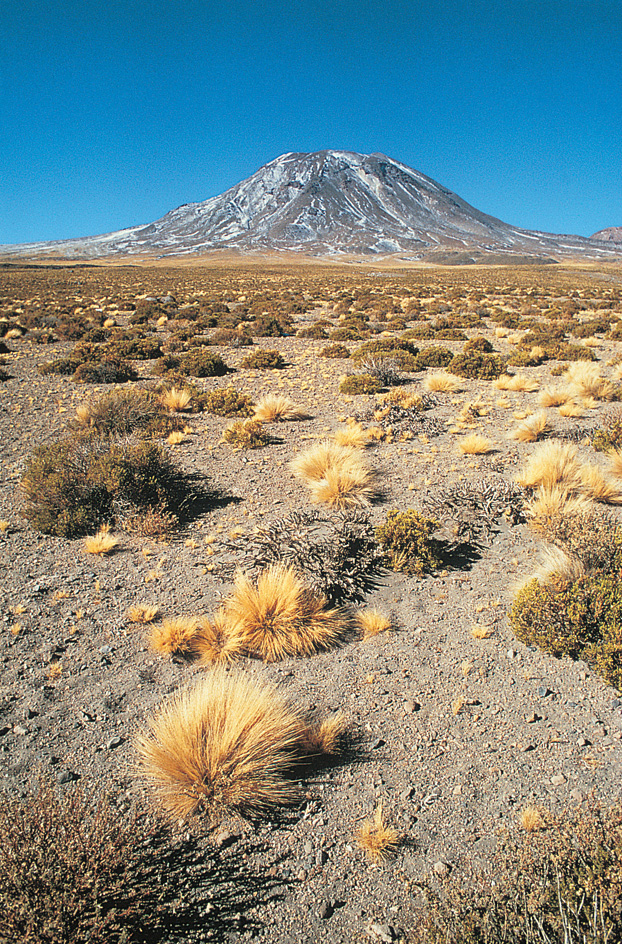

The Northern Desert

stretches 1,050 miles (1,690 kilometers) south from the Peruvian border to the Aconcagua River, just north of Valparaíso. The Atacama Desert, which Chileans call the Norte Grande (Great North), covers the northern half of the region. The Atacama is one of the world’s driest places. It gradually gives way to a slightly less arid area in the south called the Norte Chico (Little North).

Except for crops grown on a few oases, the Atacama has almost no plant life. However, the desert contains huge deposits of copper, Chile’s most valuable mineral resource. The desert also has vast deposits of sodium nitrate, which is used for fertilizers and explosives.

The Loa is the only river in the Atacama. It flows from the Andes to the Pacific. Several rivers cross the Norte Chico. However, many of them are dry part of the year.

Some cities and towns in the Northern Desert are scattered along the coast, where fishing is an important occupation. Other towns are near mining areas in the interior. The large coastal cities, such as Antofagasta and Arica, also serve as seaports. Water and other supplies for many of the region’s settlements must be brought in from other areas. A few oases in the Atacama support small farming communities. Farmers in the Norte Chico raise livestock and grow crops in irrigated river valleys.

Paranal Mountain, about 80 miles (130 kilometers) south of Antofagasta, is home to the Very Large Telescope, one of the world’s largest and most powerful telescopes. The clear desert air of the Atacama makes the region an ideal place for astronomical observations.

The Central Valley

extends about 600 miles (970 kilometers) from the Aconcagua River to the city of Puerto Montt. The Central Valley is the heartland of Chile. Industry, agriculture, and most of the nation’s population are concentrated in the region.

Runoff water from the Andes Mountains is channeled through several rivers that cross the Central Valley. The rivers include the Aconcagua, Mapocho, Maipo, Maule, and Bío-Bío. The river valleys contain Chile’s richest soil. Orchards, vineyards, pastures, and croplands cover much of the Central Valley. The region also has large deposits of coal, copper, and manganese.

An area of spectacular beauty lies south of the Bío-Bío River. Snow-capped volcanoes—some of which are still active—rise on the western slopes of the Andes. Sparkling lakes and deep valleys created by glaciers lie among heavily forested mountains. This area, which is called the Lake Country, is a popular vacation spot during the dry summers.

The Archipelago

extends about 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) from Puerto Montt to Cape Horn, the southernmost tip of South America. It is a wild region of steep, rocky slopes, dense forests, glaciers, and lakes. The region’s western edge is broken into thousands of islands pounded by the sea. In the far south, the Strait of Magellan separates mainland Chile from the group of islands known as Tierra del Fuego, which are divided between Chile and Argentina. Cape Horn, on Chile’s Horn Island, is the southernmost point of Tierra del Fuego.

Relatively few people live in the Archipelago region. Punta Arenas, on the Strait of Magellan, is the only major settlement. Most of the land is unsuitable for growing crops. However, farmers graze sheep on pastures at the southern end of the mainland and on Tierra del Fuego. The far south is also important for its oil fields. Most petroleum produced in Chile comes from the Strait of Magellan and Tierra del Fuego.

Outlying territories.

Chile owns several small islands far out in the Pacific, including Easter Island and the Juan Fernández Islands. Easter Island, about 2,300 miles (3,700 kilometers) west of the mainland, is famous for its huge stone carvings. Descendants of the Indigenous Rapanui people still live there. The Juan Fernández Islands lie about 400 miles (640 kilometers) west of Chile. See Easter Island; Juan Fernández.

Chile also claims a large pie-slice-shaped area of Antarctica. But other nations do not recognize this claim.

Climate

Chile lies south of the equator, and so its seasons are opposite those of the Northern Hemisphere. Summer lasts from late December to late March, and winter from late June to late September.

Parts of Chile’s Northern Desert may not have rain for years. But the region is not especially hot. Winds that blow across the cold Peru Current bring cool, cloudy weather and frequent fogs to the coastal area. In Antofagasta, temperatures average 69 °F (20 °C) in January and 57 °F (14 °C) in July.

The Central Valley has a mild climate, with dry summers and rainy winters. Santiago receives about 14 inches (36 centimeters) of rain annually. Temperatures in the city average 69 °F (20 °C) in January and 48 °F (9 °C) in July.

Cold rains, piercing winds, and frequent storms characterize the Archipelago. In Puerto Montt, temperatures average 59 °F (15 °C) in January and 46 °F (8 °C) in July. The city’s average annual precipitation is 86 inches (218 centimeters). Parts of the Archipelago receive up to 200 inches (500 centimeters) of rain a year.

Economy

Service industries and manufacturing account for most of Chile’s gross domestic product (GDP)—the total value of goods and services produced within a country in a year. However, mining plays a more important role in the economy of Chile than in the economies of most other countries. Copper is the most valuable resource and export. Many other industries of Chile are dependent on the country’s mineral production.

In 1971, Chile’s government began to take control of many industries and to regulate prices, wages, and trade. These actions aroused opposition among some business and military leaders. After military leaders overthrew the Chilean government in 1973, they reduced the government’s role in the economy. By 1990, when Chile returned to civilian rule, the government had sold most industries and utilities to private owners. The civilian leaders continued the privatization process. Today, Chile has one of the strongest economies in Latin America.

Service industries

account for more than half of Chile’s GDP and employ about two-thirds of the country’s workers. Many Chileans work for the government. Hotels, restaurants, and retail shops benefit from the millions of tourists who visit Chile each year. Most of these tourists come from other South American countries. Chile’s banking industry has grown steadily since the 1990’s.

Manufacturing

accounts for about one-tenth of both Chile’s GDP and its work force. Most factories produce consumer goods, such as beverages, clothing, processed foods, textiles, and wood products. Other manufactured goods include cement, chemicals, machinery, steel, and transportation equipment. Concepción, Santiago, and Valparaíso are the main industrial centers.

Agriculture

employs about 10 percent of the country’s work force but accounts for less than 5 percent of the country’s GDP. Almost all of Chile’s farmland lies in the Central Valley. Grapes are the country’s most valuable crop. Chile is an important producer and exporter of wine. Other crops include apples, corn, oats, onions, peaches, pears, potatoes, sugar beets, tomatoes, and wheat. Chile’s farmers also raise beef and dairy cattle, chickens, hogs, sheep, and turkeys.

Chile does not produce enough food for all its people, partly because only a small portion of the land can be cultivated. Most of the land is owned by small farmers or large corporations. Small farmers are often too poor to purchase modern technology to work their land. But corporate farm production is increasing. Many corporate farms grow fruits and vegetables that are exported to Europe and North America during their winters.

Mining

accounts for about one-tenth of Chile’s GDP. Most mining occurs in the northern and central parts of the country. Chile has about a fourth of the world’s known copper reserves. Chile ranks as the world’s leading copper-producing nation. Chuquicamata, in the Atacama Desert, is one of the largest open-pit copper mines in the world. The world’s largest underground copper mine, El Teniente, lies southeast of Santiago.

Chile ranks among the leading countries in the production of iodine, lithium, molybdenum, and silver. The country’s mineral products also include clays, coal, gold, iron ore, natural gas, petroleum, potash, salt, and zinc.

Fishing industry.

Chile has one of the world’s largest fishing industries. This industry yields million of tons of fish and shellfish each year. Most fishing takes place off the north coast. The leading fishing catches include anchovettas, herring, and jack mackerel. Much of the fish catch is processed into fish meal and fish oil for export. Chile also exports fresh fish, especially salmon, to Brazil, Japan, and the United States.

Energy sources.

Chile uses far more petroleum than it produces. As a result, the country must import most of the petroleum it uses. Coal, hydroelectric power, natural gas, and petroleum produce most of the country’s power.

International trade.

Chile exports more than it imports. Minerals—mainly copper—account for much of Chile’s exports. Other leading exports include beverages, chemical products, fish products, fruits, and wood products. The chief imports include chemicals, electronic equipment, machinery, motor vehicles, and petroleum. Chile trades with Argentina, Brazil, China, Japan, South Korea, and the United States.

Transportation and communication.

The Atacama Desert, the Andes Mountains, and the many islands in the south have hampered the development of transportation in Chile. In addition, most of the country’s rivers are too short and swift to serve as inland transportation routes. Until the 1900’s, ships traveling from one coastal port to another provided the main links between Chile’s regions. Today, airlines, highways, and railroads connect cities and towns in central and northern Chile. In the south, ships are still an important means of transportation. Between the late 1970’s and mid-1990’s, a road was built from Puerto Montt to the far south.

Most Chileans rely on automobiles and buses for transportation. International railways connect Chile to Argentina, Bolivia, and Peru. Santiago and Valparaíso have fine underground railway systems. Major seaports include Antofagasta, Arica, Iquique, Punta Arenas, San Antonio, San Vicente, and Valparaíso. The busiest international airport in Chile, Comodoro Arturo Merino Benítez International Airport, is near Santiago.

Chile has dozens of newspapers. The country’s leading daily newspapers include El Mercurio, La Cuarta, La Nación, La Segunda, La Tercera, and Las Últimas Noticias. The government owns a major television station. Chile also has hundreds of private radio and television stations. Cell phone and internet usage has increased since 2000.

History

Early days.

Indigenous people lived in what is now Chile long before the first Europeans arrived in the 1500’s. The Atacama, Diaguita, and other small groups lived along the north coast and at the southern edge of the Atacama Desert. They hunted game, tended llamas and alpacas, and grew a variety of crops. In the late 1400’s, they were conquered by the Inca people of Peru.

Chile’s largest Indigenous group, the Mapuche, lived in the Central Valley. They defeated the Inca, who tried to push southward into the region. The Mapuche fished and grew such crops as beans, corn, and potatoes. In the cold, wet south, the Ona and Yahgan peoples lived by hunting and fishing.

In 1520, the Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan became the first European to reach what is now Chile. He sighted the area as he sailed through the strait that now bears his name near the tip of South America.

Spanish conquest.

The Spaniards defeated the Inca of Peru by 1533 and seized their gold and silver. One of the Spanish conquerors, Diego de Almagro, set out in 1535 to explore the land south of Peru. Almagro and his men hoped to find more gold and silver. They traveled as far as the area around present-day Santiago but found only scattered Indigenous settlements with no riches.

In 1540, another Spaniard, Pedro de Valdivia, led a group of men from Peru to Chile’s Central Valley. Valdivia founded Santiago on Feb. 12, 1541. Six months later, the Mapuche destroyed it. The Spaniards rebuilt Santiago and also founded La Serena, Valparaíso, Concepción, Valdivia, and Villarrica. The Mapuche refused to give in to the Spaniards, however. In 1553, they killed Valdivia and most of his men in battle. The determined resistance of the Mapuche made southern Chile a battleground for more than 300 years.

Colonial period.

Spain ruled Chile from the 1500’s to the early 1800’s. Chile was part of a large Spanish territory called the Viceroyalty of Peru, which also included other parts of Spanish South America. The king of Spain appointed a captain-general to govern Chile, but he was under the authority of the viceroy of Peru.

Chile attracted few settlers because the Spanish explorers had found little gold or silver there. But many colonists who did come grew rich raising cattle and wheat in the Central Valley. The king of Spain granted the settlers huge tracts of land. The Spaniards enslaved the Indigenous people who lived on the land. But many native people—especially Mapuche in the south—fought the Spaniards. A frontier army was formed in southern Chile to protect settlers from Indigenous attacks.

During the colonial period, the Roman Catholic Church sent missionaries to Chile to convert the native people to Christianity. In time, the church became a powerful institution in the colony. It owned vast estates and controlled education.

Independence.

In 1808, the French Emperor Napoleon I (also known as Napoleon Bonaparte) seized control of Spain. He removed King Ferdinand VII from the throne and appointed his brother Joseph Bonaparte king of Spain. Meanwhile, a movement for independence had been growing in Chile and other Spanish lands in South America. With the French army occupying Spain, the colonies took the opportunity to revolt.

On Sept. 18, 1810, a group made up chiefly of large landowners declared Chile’s independence and formed a junta. A junta is a small group that rules by decree. A Chilean aristocrat named José Miguel Carrera became head of the government in 1811. His rule was challenged by Bernardo O’Higgins Riquelme, son of an Irish immigrant who had been viceroy of Peru. While Carrera and O’Higgins feuded, Spanish forces loyal to Ferdinand entered Chile from Peru and regained control of Chile in 1814. Carrera and O’Higgins fled to Argentina.

O’Higgins returned to Chile in 1817 with the Argentine general José de San Martín. They led an army that defeated the Spanish at Chacabuco, near Santiago. On April 5, 1818, O’Higgins and San Martín won a final victory over the Spanish at the Maipo River. O’Higgins became the new nation’s first leader.

Building the nation.

O’Higgins supervised the drafting of two constitutions for Chile—one in 1818 and the other in 1822. He established a Chilean navy, set up a system of elementary schools separate from the Catholic Church, and founded the National Library of Chile. O’Higgins also made reforms that angered some of his supporters. For example, he abolished titles of nobility, tried to break up landowners’ huge estates, and worked to reduce the power of the Catholic Church.

Soon after independence, two political parties arose in Chile. The Conservatives favored a strong central government that would carry on many of the policies of the colonial period. The Liberals supported constitutional government, land reform, and restrictions on the power of the Catholic Church. The Conservatives felt O’Higgins was too liberal, and many Liberals felt he wanted too much power. Because of this lack of support, O’Higgins was forced to resign in 1823. Weak, heavily indebted governments ruled Chile from 1823 to 1830. The Conservatives gained control of the government in 1830 after a brief civil war and stayed in power for the next 30 years.

During the 1830’s, a businessman named Diego Portales Palazuelos controlled Chile’s government through his role as a presidential adviser. Portales supervised the writing of the Constitution of 1833, which remained in effect until 1925. The Constitution established a strong central government and gave the president widespread powers. It also made Catholicism the state religion. Under this Constitution, only men older than 25 who earned more than a certain amount of income or owned more than a designated minimum amount of property could vote.

In 1836, Chile declared war on Peru and Bolivia to prevent them from forming a confederation. Chile won the war in 1839. A dispute over control of the nitrate deposits in the Atacama Desert broke out between Chile and Bolivia in the 1870’s. Peru sided with Bolivia, and the three nations fought the War of the Pacific from 1879 to 1883. Chile won the war and increased its land area by more than a third. The new territory held valuable deposits of copper as well as nitrates.

The late 1800’s to early 1900’s.

Chile’s new mineral wealth provided the resources for economic development during the late 1800’s. But political conflicts continued. For years, many Liberal political leaders had resented the broad powers of the presidency. In 1890, the situation reached a crisis when the National Congress refused to approve President José Manuel Balmaceda’s spending plans. Civil war broke out the next year, and more than 10,000 Chileans died in the fighting. Balmaceda’s forces were defeated, and he killed himself. After the civil war, Congress voted to increase its own powers and limit those of the president. Congress remained the strongest force in Chilean politics until 1925.

Beginning in the late 1800’s, earnings from nitrate exports fueled industrial growth in Chile. This growth led to an enlarged middle class of clerks, professional workers, and shopkeepers. Many workers, however, did not share in Chile’s prosperity. Rising prices led workers to strike, and sometimes to riot, to demand better working conditions and higher pay.

Chile remained neutral during World War I (1914-1918). The nation’s economy boomed because of the wartime demand for nitrates, which were used to make explosives. After the war, Germany began to export synthetic nitrates, and Chile’s export market collapsed. Unemployment surged. Strikes and riots disrupted the presidential election campaign of 1920. Many middle-class people joined forces with factory workers and miners to elect Arturo Alessandri Palma president. Alessandri pushed for political and social reforms, but Congress rejected most of his proposals. Eventually, some reforms were passed under pressure from the military.

In 1924, the military seized control of the government, and Alessandri resigned. But his supporters in the military led a second coup in 1925, and he returned to the presidency. That year, a new constitution was passed that included many of Alessandri’s reforms.

The Constitution of 1925 reduced the power of Congress and restored many presidential powers. It called for the president to be elected directly by the voters. The Constitution strengthened individual rights, including freedom of religion. Church and state became separate. The Constitution also lowered the voting age so that all men older than 21 who could read and write could vote. The income and property requirements for voters had been abolished in 1885.

In 1927, General Carlos Ibáñez del Campo became president in a rigged election. He governed as a dictator. He made several domestic reforms, expanded social welfare programs, and promoted industry. He also cracked down on labor unions and left-wing (liberal or radical) political activity. He increased government revenues but eventually began borrowing heavily to sustain high public spending. The worldwide Great Depression that began in 1929 led to economic collapse in Chile. Demonstrations forced Ibáñez to resign in 1931.

Alessandri was again elected president of Chile in 1932. The country made a slow economic recovery during his administration.

The mid-1900’s.

Chileans elected Pedro Aguirre Cerda president in 1938. The next year, the government created an economic development corporation called the Corporación de Fomento de la Producción (CORFO). With loans from the United States, CORFO built a steel mill near Concepción, developed hydroelectric facilities, and established a sugar beet industry.

Chile was neutral at the start of World War II (1939-1945), but it broke relations with Germany and Japan in 1943. Chile sold copper, nitrates, and other war supplies to the Allies. Economic development projects continued during the 1940’s under Presidents Juan Antonio Ríos and Gabriel González Videla. Chilean women gained the right to vote in national elections in 1949.

Chile’s economy began having problems during the 1940’s and 1950’s. The economy was too dependent on income from copper export taxes. High inflation in the late 1940’s led to worker rebellions, which the government crushed. Deep political divisions developed between conservative, moderate, and left-wing groups. Former President Ibáñez became president again in 1952. He pledged to rise above party politics, curb inflation, and address the problems of Chile’s poor. But government mismanagement and continuing economic problems led Chileans to be discouraged by his administration.

In 1958, Jorge Alessandri Rodríguez, a son of Arturo Alessandri, was elected president. He reduced taxes on businesses and attracted some foreign investment. Although his conservative policies initially helped stabilize the economy, inflation remained a problem. In 1960, a series of earthquakes and a tsunami struck Chile. These disasters killed thousands, caused several hundred million dollars in damage, and added to Chile’s economic difficulties.

Chileans elected Eduardo Frei Montalva president in 1964. Frei set up programs for land reform, public housing construction, and investment in education. During Frei’s presidency, the United States provided financial aid to Chile through the Alliance for Progress, a cooperative economic development program. This aid allowed Frei to spend more on social reforms and to buy partial control of copper mines from their U.S. owners. Frei’s programs did not satisfy Chile’s right-wing (conservative) and left-wing political parties, which became even more divided over the pace of political, economic, and social change.

Socialism and military rule.

Salvador Allende Gossens was elected president in 1970. He ran on a program to make Chile a socialist state—that is, one in which industries and businesses are owned by the government. He was the first Marxist to be elected democratically to head a nation in the Western Hemisphere. A Marxist follows the socialist theories of the German philosopher and economist Karl Marx. The Allende government took over ownership of the copper mines, many banks, and numerous other industries. It also implemented a broad land reform program. Many rural Chileans seized land illegally while the program was being carried out.

The Allende government approved sharp increases in the minimum wage at the same time that it tried to prevent increases in the price of consumer goods. Food shortages became widespread. Inflation soared from about 20 percent in 1971 to more than 350 percent in 1973. Strikes became common, and both supporters and opponents of Allende staged violent demonstrations. Opposition from Congress and the middle and upper classes further weakened Allende’s government. The Soviet Union and Cuba supported Allende, but the United States and U.S. firms in Chile assisted Allende’s opponents. The U.S. government cut off aid to the Chilean government. Also, U.S. intelligence agencies encouraged right-wing paramilitary groups and military leaders who were plotting to seize control of the government.

On Sept. 11, 1973, the military overthrew the government. As jets and troops attacked the presidential palace, Allende took his own life rather than surrender and resign.

The new military junta that took control of Chile dissolved Congress, censored the press, cracked down on labor and land reform movements, and banned political parties. Many left-wing party, union, and peasant leaders were murdered. Thousands of people were tortured. Supporters of Allende were imprisoned or forced into exile. Most industries that the Allende government had taken over were returned to the previous owners. The military government, however, kept control of the copper mines.

General Augusto Pinochet Ugarte became the dominant figure of the junta and president of Chile in 1974. Pinochet used state violence to silence his opponents. He radically changed Chile’s economy to promote capitalism. He cut government spending and social subsidies, lowered tariffs, and opened Chilean markets to massive imports. Wages fell, industries closed, and the working poor faced starvation. Gradually, however, private industry recovered, prospering between 1976 and 1981. Chile began exporting more fruits, vegetables, fish, and forestry products to advanced economies. Except for brief periods, the U.S. government supported the Pinochet regime with financial aid.

In 1980, a new constitution was approved in a plebiscite (vote of the people) controlled by Pinochet. Under the new set of laws, presidential powers were greatly expanded, and the military’s role in government was formally established. The 1980 Constitution also provided for a vote in 1988 on whether Pinochet’s rule should continue.

In 1982 and 1983, Chile’s economy collapsed. Strikes and demonstrations threatened to end Pinochet’s government. But a renewed crackdown on government opponents allowed Pinochet to hang on to power until the economy began to recover later in the 1980’s. In 1987, he allowed some political parties to reenter public life. Many people in exile began returning to Chile.

Return to democracy.

In 1988, Chile held a plebiscite on Pinochet’s rule. The vote resulted in his defeat. Another plebiscite in 1989 approved constitutional reforms that restored civil liberties. Later that year, elections were held for a civilian president and a two-house Congress. Patricio Aylwin Azócar, a member of the centrist Christian Democratic Party, won the presidency. Aylwin represented the Concertación, or Coalition of Parties for Democracy, which included Christian Democrats and Socialists.

Despite the 1989 reforms, the 1980 Constitution limited what the new government could do. Rules had been imposed to prohibit a return to socialism. Pinochet remained head of the army, and his supporters dominated the Senate. Aylwin created some social programs to ease the poverty that had existed during Pinochet’s rule. But Aylwin did not change the free-market basis of the economy.

During the 1990’s, Chile’s economy boomed. The country experienced low inflation and unemployment; an expansion of the middle class; and steady investment in education and basic social welfare measures. Concertación candidates Eduardo Frei Ruíz-Tagle and Ricardo Lagos Escobar won presidential elections in 1993 and 2000, respectively.

Pinochet remained head of Chile’s army until 1998, when he became a senator for life. In the late 1990’s and early 2000’s, Pinochet faced legal charges of crimes against humanity, covering up kidnappings and murders, and tax fraud. In most of the cases, officials ruled that he was not well enough to stand trial. He died in 2006.

The early 2000’s.

In 2006, Chileans elected Michelle Bachelet, a Socialist, as the country’s first woman president. In 2010, conservative candidate and businessman Sebastián Piñera was elected president following two decades of leftist government. Also in 2010, a powerful earthquake struck central Chile, killing several hundred people. Bachelet was reelected president in 2013, and Piñera was reelected in 2017. Piñera took office in 2018.

Mass demonstrations erupted in Chile in 2019. Although the nation’s economy was doing well overall, many Chileans were frustrated by income inequality, low wages, and a high cost of living. The military was deployed to control the protests. A number of people were killed. Thousands of others were injured and arrested, amid reports of abuses by police and troops. In response to the protests, the government initiated some social reforms. It also began a democratic process to create a new national constitution. But Chileans rejected two draft constitutions by popular vote in 2022 and 2023.

The COVID-19 pandemic (global outbreak of disease) that began in 2020 greatly impacted Chile’s public health and strained its economy. COVID-19 is a respiratory disease caused by a coronavirus. Measures to curb the outbreak in Chile included restricting people’s activities and movements. However, social and economic conditions made it difficult for many people to observe the public restrictions. As of early 2023, there had been more than 5 million confirmed cases of the virus in Chile, and more than 60,000 confirmed deaths from COVID-19. By then, most of the population had received some protection in the form of vaccines.

Gabriel Boric, the candidate of the leftist coalition Frente Amplio (Broad Front), was elected president of Chile in 2021. Boric, a former legislator and student activist, took office in 2022.

In February 2024, wildfires killed more than 130 people in central Chile, and many other people were reported missing. Communities that suffered significant damage included the cities of Viña del Mar and Quilpué.