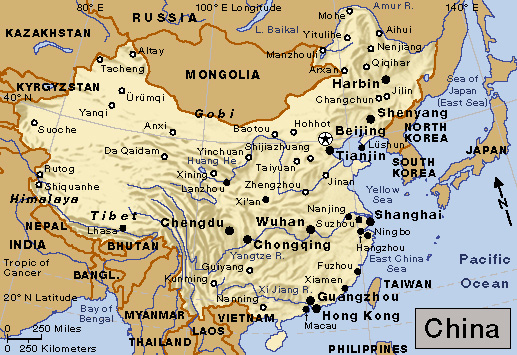

China is a large country in eastern Asia. It is the world’s second largest country in population with about 1.4 billion people—approximately 20 percent of all the people in the world. Only India has more people. China is the third largest country in area. Only Russia and Canada have more territory. China is also one of the world’s oldest countries, with a rich history that stretches over thousands of years.

The Chinese call their country Zhongguo, which means Middle Country. This name probably came from the ancient Chinese belief that their civilization was at the geographical center of the world and was the most cultured. The English name China probably came from Qin << chihn >>, the name of an early Chinese dynasty (series of rulers from the same family).

More than 90 percent of China’s people live in the eastern half of China, which has most of China’s major cities and nearly all the land suitable for farming. Western China, by contrast, has far fewer people and resources. It is home to many of the country’s minority groups.

Until recently, agriculture had always been the chief economic activity in China. Today, less than half of the people live in rural villages, and only about a quarter of all workers are farmers. China has some of the world’s largest cities. They include Shanghai and Beijing (also spelled Peking), the nation’s capital.

China is one of the world’s oldest living civilizations. Its written history goes back about 3,500 years. The Chinese were the first to develop the compass, paper, and porcelain. They undertook huge construction projects, such as the Great Wall. Over the centuries, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and other Asian lands borrowed from Chinese art, language, literature, religion, and technology.

In early times, the country that is now China was divided into small states, which were sometimes allied and sometimes at war. In 221 B.C., the Qin state conquered the other kingdoms and created a strong central government, forming the first united Chinese empire. Such empires continued to rule for more than 2,000 years. Chinese empires expanded the country’s territory, built great cities, and sponsored magnificent works of literature and art. Nomadic groups from the north sometimes conquered all or part of the country. But the invaders generally adopted more from Chinese civilization than the Chinese adopted from them.

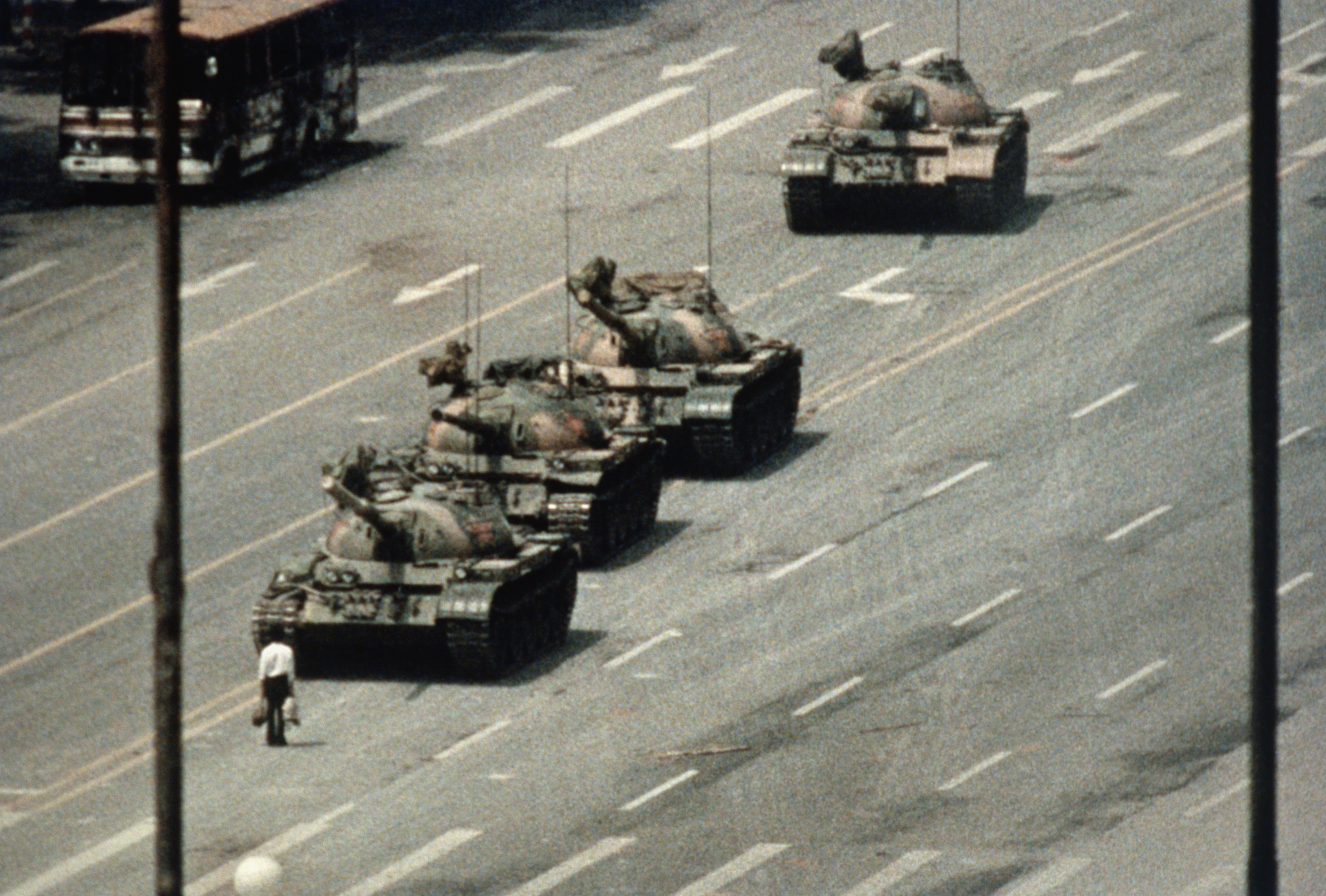

In the 1800’s, China’s last empire, the Qing, began to weaken. In 1911, revolutionaries overthrew the Qing, and the next year, China became a republic. However, the Nationalist Party, which ruled the republic, never established effective government over all of China. In 1949, the Chinese Communist Party defeated the Nationalists and set up China’s present government. The Communists called the country Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo (People’s Republic of China). The Nationalists fled to the island of Taiwan, where they reestablished their government. The People’s Republic claims that Taiwan should be part of its territory. This article discusses only the People’s Republic of China. For information about Taiwan, which Nationalists call the Republic of China, see the World Book article on Taiwan.

The Communists made many major changes in China. They placed all important industries under state ownership and direction, and they redistributed agricultural land to the peasants. The government also took control of most trade and finance. In the late 1900’s, the Communists began to loosen their grip on the nation’s economy and to allow more free enterprise. China has one of the world’s largest economies, and many of its people prosper. However, the majority of people still live modestly.

Government

China’s government is dominated by the Chinese Communist Party, the military, and a branch of government known as the State Council. The Communist Party is the most powerful group. People holding positions in the party or the government are called cadres or ganbu.

China's national anthem

The Communist Party.

China remains a one-party state. A number of minor political parties exist, but they have no power. Tens of millions of Chinese citizens belong to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), but members make up only a small percentage of the total population. In 2002, the party began allowing business owners to join. Admitting business owners was a major change because Communists traditionally had considered the owners of businesses and other means of production to be enemies of the working class. Although the party still supports socialist ideals, it has recognized that business owners play an important role in modern China.

The Communist Party has four main administrative bodies: the National Party Congress, the Central Committee, the Politburo (Political Bureau), and the Secretariat. The National Party Congress has about 2,300 representatives, selected by party members throughout the nation. The Central Committee consists of leading party members and is elected by the National Party Congress. The Central Committee has about 200 voting members and more than 170 alternates. The Politburo has about 25 members, who are top party leaders elected by the Central Committee. The Standing Committee is a smaller group within the Politburo and is made up of some of the most important members of the Communist Party. In addition, several powerful leaders belong to the Secretariat, which is chosen by the Central Committee.

The Communist Party’s constitution states that the National Party Congress and the Central Committee are the most important bodies, but they have little real power. In general, they automatically approve party policies and guidelines set by the Politburo and its Standing Committee. The Secretariat is responsible for carrying out the day-to-day activities of the party.

The highest post in the Communist Party is that of general secretary, who serves as head of the Secretariat. Sometimes other high-ranking government officials have held more power. For example, Deng Xiaoping was China’s most influential leader from the late 1970’s until the early 1990’s, even though Hu Yaobang and others held the post of general secretary. Since 2012, however, Xi Jinping has been the general secretary, and he is also the nation’s paramount leader.

National government.

China’s Constitution establishes the National People’s Congress as the highest government authority. Members of the National People’s Congress are elected by local and regional people’s congresses and by the armed forces. The members of the National People’s Congress serve five-year terms. The chief function of the congress is legislative. Its powers include adopting laws, approving the national budget, and appointing government officials. A standing committee of about 150 members handles the work of the congress when it is not in session.

The State Council serves as the executive branch. It carries on the day-to-day affairs of the government. The council is led by the premier, China’s head of government. The premier is chosen by the National People’s Congress, upon nomination by the president. The president’s duties are largely ceremonial. The premier is assisted by vice premiers, state councilors, and a number of ministers and heads of special commissions. The ministers are in charge of government departments, such as the ministries of defense, education, and finance.

Political divisions.

Mainland China has 33 major political divisions—22 provinces, 5 autonomous (self-governing) regions, 4 nationally governed municipalities, and 2 special administrative regions. The government of the People’s Republic of China also claims Taiwan and regards the island as its 23rd province, but Taiwan remains effectively independent.

China’s autonomous regions—Guangxi, Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, Tibet, and Xinjiang—have many people who belong to the country’s minority ethnic groups. Although the regions are called autonomous, they are actually governed much like the rest of the nation. The nationally governed municipalities—Beijing, Chongqing, Shanghai, and Tianjin —are large metropolitan areas that are administered by the national government. Each of these municipalities consists of an urban center and a rural area. The special administrative regions are Hong Kong and Macau, which were controlled for many years by the United Kingdom and Portugal, respectively. Hong Kong and Macau have their own executive, legislative, and judicial bodies. China handles their defense and foreign policy.

China has three levels of local government. The major political units are divided into more than 300 prefectures and more than 650 major cities. Counties, other cities, and districts of major cities make up the next level. The counties are subdivided into thousands of townships and towns. Each political unit has a people’s congress with a standing committee, and an executive body patterned after the State Council.

Courts

in China do not function as a completely independent branch of government as they do in many Western nations. Instead, the courts base their decisions largely on the policies of the Communist Party.

The highest court in China is the Supreme People’s Court. It interprets the national laws and supervises the local people’s courts. It also makes the final judgment on cases that have been appealed from lower courts. The Supreme People’s Procuratorate hears cases that involve violations by government officials and sees that the national Constitution and the regulations of the National People’s Congress are observed.

The armed forces

of China are jointly commanded by the Central Military Commission of the Communist Party and the Central Military Commission of the government. China has an army, navy, and air force, which together make up the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). The PLA has more than 2 million male and female regular members. There are also about 1 million army reserves and military police. Millions of men and women serve in China’s militia (citizens’ army). Men and women from 18 to 22 years of age may be drafted for military service.

The armed forces hold enormous political power in the People’s Republic of China. Military officers make up a large percentage of the members on the Communist Party’s Central Committee. In addition to its military duties, the People’s Liberation Army helps carry out party policies and programs.

People

Population.

About a fifth of the world’s people live in China. Shanghai is China’s largest city, and one of the world’s largest as well. Beijing, the country’s capital, is the second largest city. More than 100 Chinese cities each have more than a million people. About 40 percent of the country’s people live in rural villages and small towns. The population is concentrated in eastern China. Less than 10 percent of the people live in the western half of the country.

China’s government has seen the country’s population as both a resource and a burden. China’s huge work force makes its economy one of the most powerful in the world. But in the past, without limits placed on population growth, far more children would have been born than China could have adequately fed, housed, educated, or employed. Strict population control policies introduced in 1979 encouraged people to postpone marriage until their late 20’s and usually to have only one child. The policies were relaxed somewhat in the mid-2010’s and early 2020’s to allow two, and later three, children. By the start of the 2020’s, however, China’s birth rate had become so low that without an increase, it would not produce enough young people to support the nation’s rapidly growing elderly population, potentially creating an economic crisis. In 2022, China’s population shrank for the first time since the early 1960’s. This change marked the beginning of what population experts predicted would be a long-term population decline.

Nationalities.

About 92 percent of the people of China belong to the Han nationality. The rest of the population consists of more than 50 minority groups, including Kazakhs, Mongols, Tibetans, Uyghurs (also spelled Uighurs), and Zhuang. The different nationality groups are distinguished chiefly by language and culture.

Most of China’s minority peoples live in the border regions and western China. A few groups, such as the Mongols in the north and the Kazakhs in the northwest, have a long tradition of herding sheep, goats, and other livestock. Some are still nomads, moving from place to place during the year to feed their herds on fresh pastures. The Uyghurs raise livestock and grow crops on oases in the deserts of northwestern China. The Tibetan people practice simple forms of agriculture and herding in China’s southwestern highlands. Many Koreans are farmers near the border with North Korea.

A number of minority groups inhabit the far southern parts of China. Some of these groups, such as the Zhuang, live much like their neighbors, the Han. Other minority groups are related to the peoples of Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, or Tibet. Many of these people, who live in less developed mountain areas, retain their traditional language and way of life.

Languages.

Chinese, the native language of the Han, is actually a group of closely related languages. Early in the 1900’s, China’s government made northern Chinese, which was spoken in Beijing, the official language. This version of Chinese is often called Mandarin in English, but the Chinese call it Putonghua (common language). Most people in northern China speak Putonghua, and it is the language of instruction in almost all schools. Other varieties of Chinese include Northern Min (spoken in northern Fujian province), Southern Min (spoken mainly in Guangdong, Hainan, and southern Fujian), Wu (spoken in Shanghai, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang), and Yue or Cantonese (spoken in Guangdong and Guangxi). Each language has several local dialects.

Although each version of Chinese has its own pronunciation, all Chinese is written in a similar way. The Chinese writing system uses characters instead of an alphabet. Each character is a symbol that represents a word or part of a word. For more information, see Chinese language.

The minority peoples of China speak many languages, including Korean, Mongolian, Uyghur (also spelled Uighur), and Zhuang. Many groups use their own language in their schools and publications. Many members of China’s minority groups learn Chinese as a second language. A few minority groups speak Chinese as their primary language.

Way of life

Family life

has always been extremely important in Chinese culture. For thousands of years, the Chinese people practiced loyalty to family, obedience to the father, and reverence for ancestors. Chinese philosophy and religion emphasized these values. In the mid-1900’s, the Communists tried to replace loyalty to the family with loyalty to the work group. Other social and economic changes in the late 1900’s further disrupted traditional family values.

Relationships within Chinese families have become less formal, and parents no longer expect their children to show unquestioning obedience. In the past, parents arranged marriages and chose whom the children would marry. Many young people today choose their own marriage partners, although usually with the consent of their parents. Parents still help arrange some marriages in rural areas.

Chinese families traditionally valued sons far more than daughters. A husband could divorce his wife if she failed to give birth to sons. In some cases, poor families killed daughters at birth to save resources for the sons. Today, social policy stresses that families should value girls and boys equally. The Communist government established a law in 1950 that recognized men and women as equal. It supports the idea that women should contribute to the family income and participate in social and political activities. Women do many kinds of work outside the home. Many husbands share in the shopping, housecleaning, cooking, and caring for the children. However, equality between the sexes is more widely accepted in the cities than in the countryside.

Rural life.

Traditionally, most Chinese people lived in small villages. Many families owned their land, though it was often not large enough to support them. Many other families owned no land but worked as tenants or laborers for landowners and rich farmers.

After the Communists took control of China, they organized a collective ownership system, in which large groups of peasants owned land, tools, work animals, and workshops in common. The highest level of the collective system was the commune, which administered the economic activity for groups of about 5,000 families. Smaller units called production brigades were further divided into production teams, which were the equivalent of a small village. These units planned and performed most day-to-day farm work. In some cases, each family owned its house and a plot on which it could grow vegetables and raise chickens or hogs for its own use. If a family grew a surplus of crops, it could sell the surplus in a local market.

In 1979, the government began a new system to gradually abolish communes, brigades, and teams. Now, cooperative groups known as collectives make contracts with individual families. The contract tells how much land a family can work, what crops and livestock the family will raise, and how much it will sell to the government at a set price. After fulfilling its contract, the farm family may use the remainder of its production as it wishes. Most families use some for food and sell the rest on the open market.

Some rural families sign contracts as specialized households. These households may specialize in raising only one commodity, such as chickens or silkworms. Or they may provide farm machinery, repairs, or handicrafts on the free market instead of doing full-time farm work. After paying an agreed amount to the government, the specialized household keeps any profit. Some households operate businesses or small factories and hire employees. Some of them have become relatively wealthy.

The standard of living in rural China is much higher now than it was before the Communists came to power. The average income in rural areas is still low, but most rural families have enough food and clothing and also own a bicycle or motor scooter, and a radio or television. Some own such appliances as a refrigerator or a washing machine. Most rural families live in five- or six-room houses. Older houses are made of wood or mud bricks and have a tile or thatched roof. Newer houses are made of clay bricks or stone and have a tile roof. Some villages have apartment buildings. Except in remote areas, most houses and apartments have electric power.

Rural people work many hours a day, especially during planting and harvesting time. Even so, they have time for recreation. Many villages have a small library and a recreation center with a television and sometimes a computer. Villages may also have sports facilities, music groups, or theater groups. Today, many rural adults, especially young adults, migrate to cities, where they work equally long hours in factories or at other jobs.

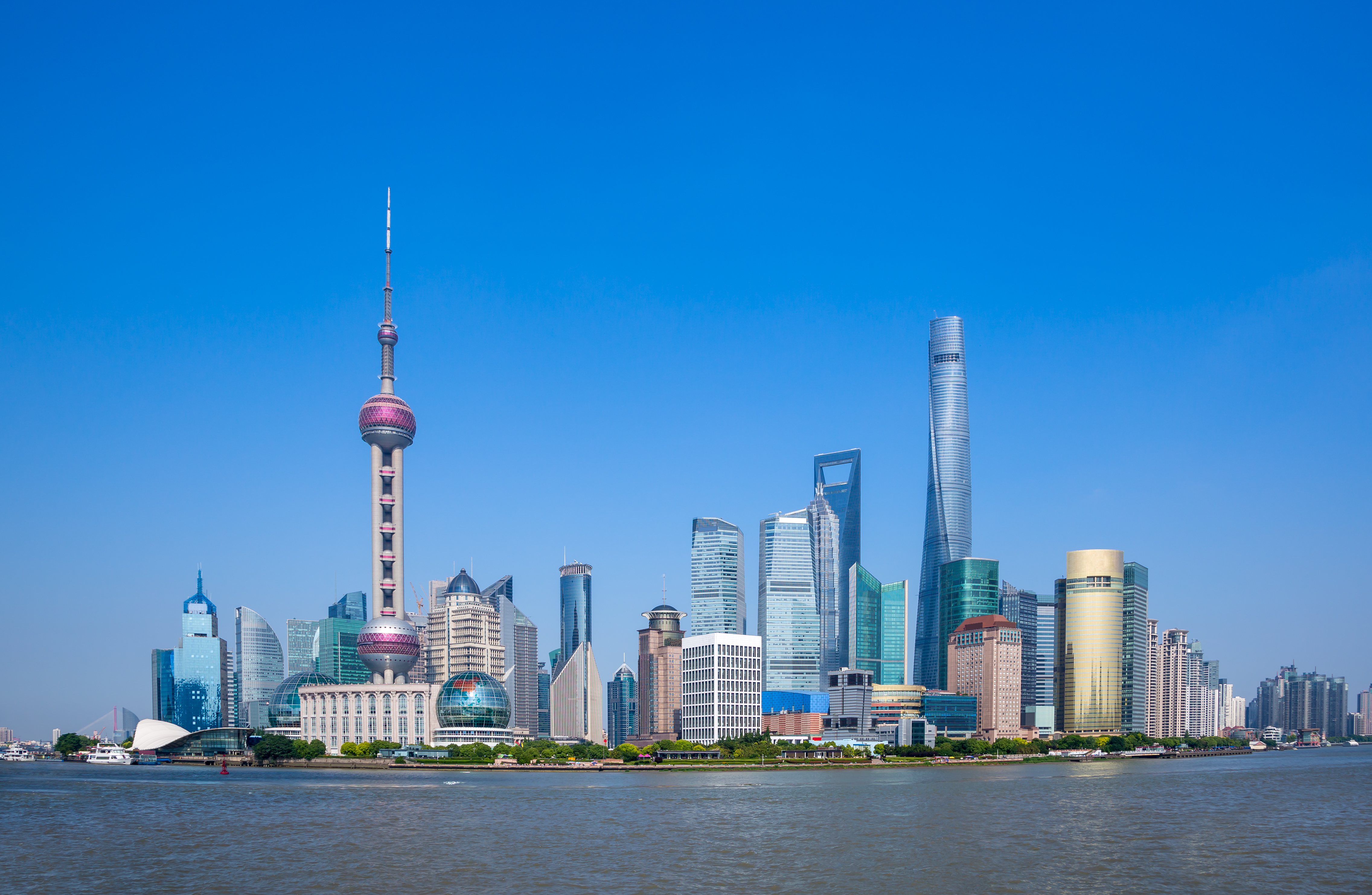

City life.

China’s cities are crowded, and housing is in great demand. Many city residents live in older neighborhoods where the houses resemble those in the countryside. Many other city dwellers live in large new apartment complexes. City governments construct some apartment buildings, and large businesses build others to house their workers. Most families pay rent for their apartments, but some have the opportunity to buy them.

Most city neighborhoods or apartment complexes have an elected residents’ committee, also called a neighborhood committee. The committee supervises various neighborhood facilities and programs, such as day-care centers, evening classes, and after-school activities for children. When fights, petty crimes, or acts of juvenile delinquency occur in the neighborhoods, committee members talk with the people involved and try to help them solve the problem. These neighborhood organizations seek to keep crime from becoming a serious problem despite the overcrowding in China’s cities.

In general, people in China’s cities have a higher standard of living than people in the countryside. Wages are low compared with those of workers in Western industrial countries. However, most households have at least two wage earners, and rents and the cost of food are low. Most city people can afford a bicycle or motor scooter, a television set, and some household appliances. Some are able to buy a computer or a car. City people have more cultural advantages than rural people have. They can attend a greater variety of classes and meetings to further their education. Cities typically have more theaters, museums, and other cultural activities.

Food.

Grains are the main foods in China. Rice is the favorite grain among people in the south. In the north, people prefer wheat, which they make into dumplings and noodles. Corn, millet, and sorghum are also eaten. Vegetables, especially cabbages and tofu (soybean curd), rank second in the Chinese diet. Pork and poultry are favorite meats. People in China also like eggs, fish, fruits, and shellfish. Fast food, such as hamburgers and french fries, has become popular in China’s cities.

Breakfast foods in China include rice porridge, steamed buns, and deep-fried pastries that taste like doughnuts. Favorite lunchtime foods include rice with vegetables or meat, noodles, and dumplings. A typical main meal includes vegetables with bits of meat or seafood, soup, and rice or noodles. Chopsticks and soup spoons serve as the utensils at Chinese meals.

Tea is the traditional favorite Chinese beverage. Soft drinks and beer have also become popular. Ice cream is a favorite treat in China’s cities.

Fancy Chinese cooking varies from region to region. Beijing (also spelled Peking) duck is a northern specialty. It consists of slices of crisp roast duck eaten with thin rolled pancakes and a sweet sauce made from soybean paste. Foods from the coastal areas include fish, crab, and shrimp. The spiciest foods come from Sichuan and Hunan. Chinese cooks vary the texture of dishes by adding crunchy bamboo shoots and water chestnuts (thickened stems of an aquatic plant). The Chinese occasionally eat things rarely used as food elsewhere, such as tiger lily buds, sea animals called sea cucumbers, and snake meat. Shark’s fin soup has long been considered an expensive delicacy. However, it has become less popular in China, as the shark population is threatened with extinction.

Recreation.

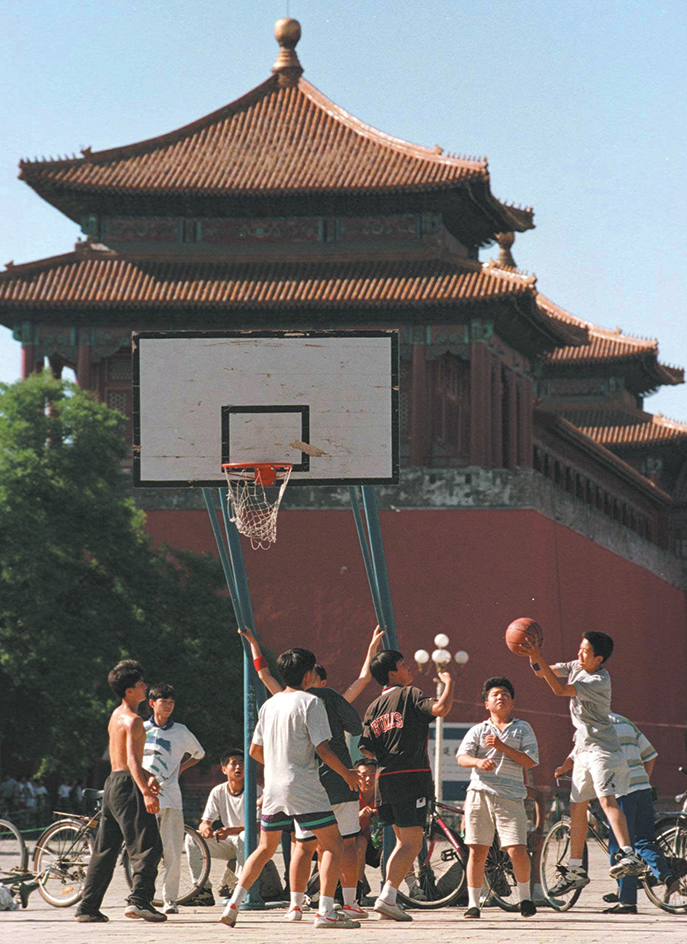

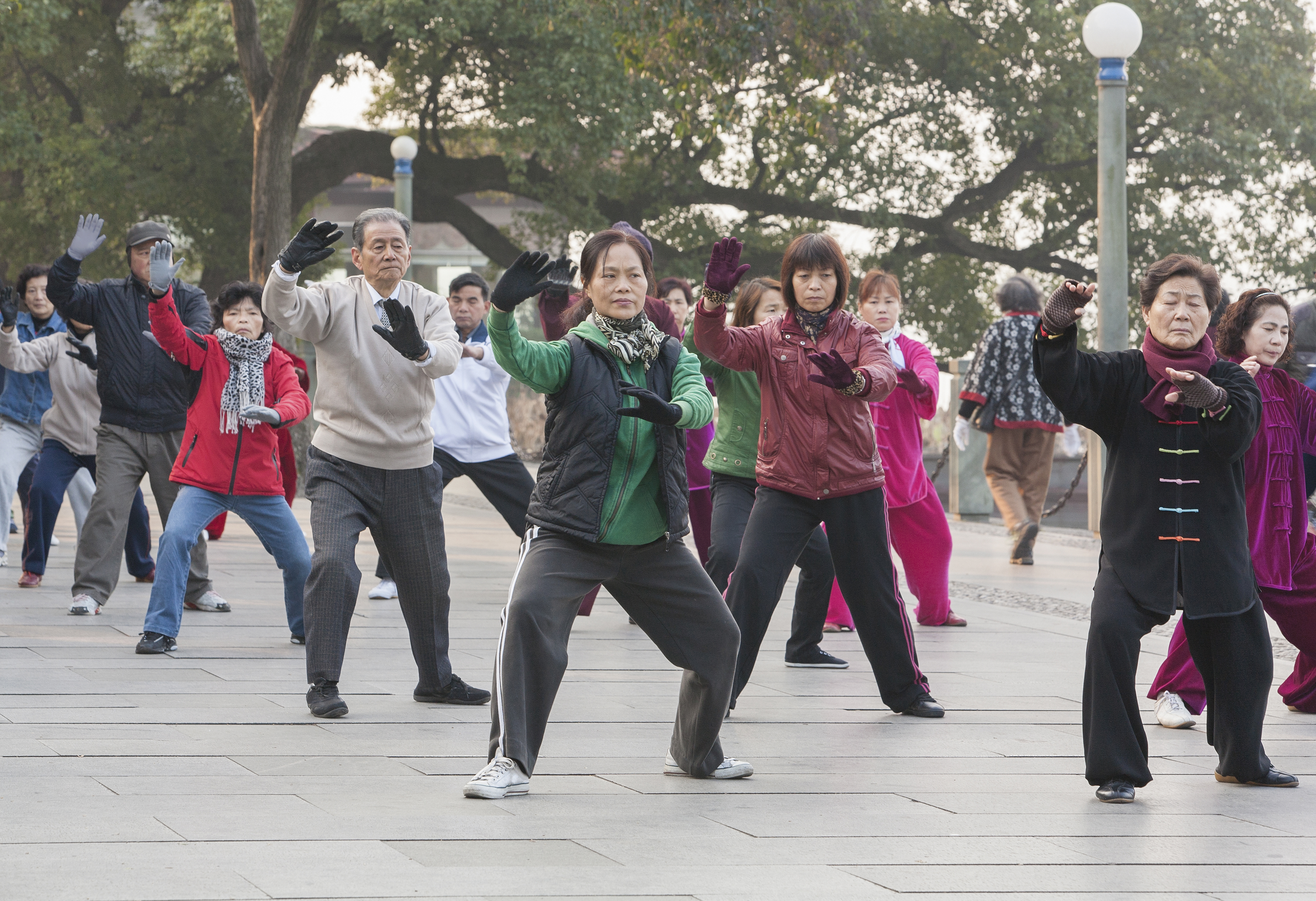

The Chinese enjoy many recreational activities that are popular throughout the world. Watching television, listening to music, reading, going to the movies or opera, and shopping are common. Karaoke clubs, where guests sing along to recorded music, have become popular. Badminton, basketball, soccer, and table tennis are favorite sports. People often invite guests over for meals, but going to restaurants is also popular. Many urban youth use computers at internet cafes.

Traditional Chinese martial arts, such as t’ai chi ch’uan (also written taijiquan), are popular. Ballroom dancing parties take place both indoors and outdoors. In parks, the Chinese play xiang qi (a Chinese version of chess) and Chinese card games. Another favorite game is mah-jongg, which is played with engraved tiles.

Clothing.

Most Chinese people wear clothing similar to that of Europeans and North Americans. In urban areas, fashionable designs are popular, especially among younger people. Members of certain religious and ethnic groups may wear special costumes and headgear.

Health care

in China combines traditional Chinese medicine and modern Western medicine. Traditional medicine is based on the use of herbs, attention to diet, and ancient treatments, such as acupuncture. In acupuncture, thin needles are inserted into the body at certain points to relieve pain or treat disease. From Western medicine, the Chinese have adopted many drugs and surgical methods.

Hospitals and clinics in China may be either publicly or privately owned. Hospitals in large cities provide access to advanced medical technologies. In rural areas, some villages have medical workers or rural doctors, although some of them do not have much medical training. Village health care providers can treat simple cases and prescribe drugs. For more advanced care, rural Chinese may have to travel a great distance to reach a township health center or a county hospital.

Beginning in the late 1970’s, China’s government greatly reduced health care funding. Now, patients are expected to pay more of their health care expenses. Most urban residents live near good facilities and can afford to pay for care, but they often have long waits to see doctors in China’s crowded hospitals. Many rural people no longer have access to affordable health care.

Religion

is tolerated, but restricted, by the Communist government of China. However, it played an important part in traditional Chinese life. Confucianism, Taoism (also spelled Daoism), and Buddhism were major religions throughout most of China’s history. The religious beliefs of many Chinese people included elements of all three.

Confucianism is based on the ideas of Confucius, a Chinese philosopher born about 550 B.C. Confucian belief stresses the importance of ethical standards and of a well-ordered society. In the ideal Confucian society, parents have the right to rule their children, men to rule women, and the educated to rule the common people. Confucianism strongly emphasizes deep respect for one’s ancestors and for the past.

Taoism, also native to China, teaches that a person should live in harmony with nature. Taoism began during the 300’s B.C. and is based largely on the book Tao Te Ching (The Classic of the Way and the Virtue). It came to include many elements of Chinese folk religion and so became a religion with many protective gods.

Buddhism reached China from India before A.D. 100 and became well established throughout the country during the 300’s. Under the influence of Taoism, Chinese varieties of Buddhism developed. They taught strict moral standards and the ideas of rebirth and life after death. The Chinese Buddhists worshiped many gods and appealed to them for help.

China’s Communist government regarded religion as a part of China’s past that would die out. It expected scientific and Marxist thought to replace religion and for many years persecuted religious believers. The Communists destroyed some Taoist and Buddhist temples and other religious buildings, and they turned others into museums, schools, and meeting halls. Beginning in the 1970’s, the government adopted a more tolerant attitude toward religion. It now allows open practice of religion and the publication of religious works. It restored and reopened some religious buildings. Nonetheless, the government still tries to control religious organizations.

Christian missionaries worked in China for many years before the Communists came to power. The Communists expelled foreign missionaries and closed most Christian churches. In the late 1900’s, the government permitted many Christian churches to reopen, but it suppressed Christian movements that organized outside of government control.

Muslims make up a small percentage of the Chinese population. They live mainly in northwestern China. The Hui (ethnic Chinese Muslims) and the Uyghurs are the largest of several traditionally Muslim groups in the country.

A spiritual movement called Falun Gong appeared in China in the early 1990’s and grew rapidly. Falun Gong teaches techniques of meditation through exercises as a means of improving physical health and spiritual purity. In 1999, members of Falun Gong staged a 10,000-person demonstration outside central government buildings in Beijing. This demonstration led the Chinese government to suppress Falun Gong and to issue an arrest warrant for its founder. The group nevertheless continues to claim many followers in China.

Education.

The Chinese have always prized education and respected scholars. The Confucians believed that people could perfect themselves through study. They made no sharp distinction between academic education and moral education. For many years, candidates for government jobs had to pass an examination based on classical Confucian works.

The Communists regard education as a key to reaching their goals. They have conducted literacy programs in rural areas in an effort to teach all China’s people to read and write. In the 1950’s, they began a language reform program to help reduce illiteracy. The program included simplifying more than 2,000 of the most basic Chinese characters by reducing the number of strokes in each character. Such changes helped make Chinese easier to write. Today, almost all Chinese people 15 years of age or older can read and write.

Moral education is important in China. However, the Chinese teach morality as defined in a Communist sense. They say students should be both politically committed to Communist ideas and technically skilled. Courses in China combine the teaching of academic facts and political values.

In the mid-1980’s, China’s government began trying to get children to attend school for at least nine years. Students who show outstanding ability on nationwide examinations go to key schools, which have the best faculties and facilities. Key schools offer education at the elementary, secondary, and college levels. Some private schools exist, although their fees are high.

Elementary and secondary schools.

Children in China enter elementary school at the age of 6 or 7. Nearly all of the country’s children attend elementary school, which lasts for 5 or 6 years. Elementary school courses include art, Chinese, English, geography, history, mathematics, music, science, physical education, and political education.

After elementary school, students may enter secondary schools called middle schools. Junior middle school lasts three years. Senior middle school continues for another two or three years. Middle school courses include many subjects studied in elementary school, plus biology, chemistry, physics, and foreign languages. Technical and vocational middle schools offer training in agriculture, industrial technology, and other work-related subjects. Almost all elementary school graduates enter middle school, but far fewer continue on to the senior level.

Higher education.

Nationwide examinations determine who may advance to higher education and at what kind of school. Students study intensely for the tests. Those who do best on the tests enter a university. Some wealthier students who do not qualify may pay to attend private universities. The chief university subjects include economics, education, engineering, literature, medicine, and science.

Others who pass the tests with lower scores may enter a technical college or vocational university. These schools train students for jobs in business and industry. Many students complete two- or three-year programs in such fields as agriculture, industrial arts, and nursing.

China has about 2,500 institutions of higher learning, including both universities and schools for adult education. The number of students who desire a university education exceeds the number of openings available, and many attend colleges overseas. In addition to technical and vocational schools, adult students can continue their education at “workers’ colleges” run by factories. These schools offer short-term courses for employees. Other adult education includes part-time study; radio, television, and correspondence courses; and distance learning programs conducted over the internet.

The arts

The Chinese have one of the longest and greatest artistic traditions in the world. Chinese pottery and jade from the 4000’s B.C. showed a great deal of technical skill and artistic refinement. During the Shang (1766-1045 B.C.) and Zhou (1045-256 B.C.) dynasties, Chinese metalworkers excelled in bronzework. Late in the Zhou dynasty, the Chinese produced remarkable textiles and lacquered items. Most early Chinese art reflected the power and mystery of nature. But around 200 B.C., Chinese art and literature began to focus on mythical and historical figures, and human situations and values. See Bronze; Furniture (In China); Ivory.

By the Song dynasty (A.D. 960-1279), nature was again a prominent theme in Chinese art and literature. Artists emphasized the balance between two principal forces of nature, called yin and yang. Landscape painters, for example, aimed for harmony, rhythm, and balance in their compositions. Chinese writers, musicians, and architects also tried to capture these qualities in their work.

In the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, European and American culture began to influence Chinese life, including the arts. After the Chinese Communists gained control of the country in 1949, they required art and literature to express Communist values and ideals. Since the late 1970’s, the government has relaxed its demands, allowing the revival of Chinese traditions in the arts and permitting experimentation in non-Chinese styles.

Literature.

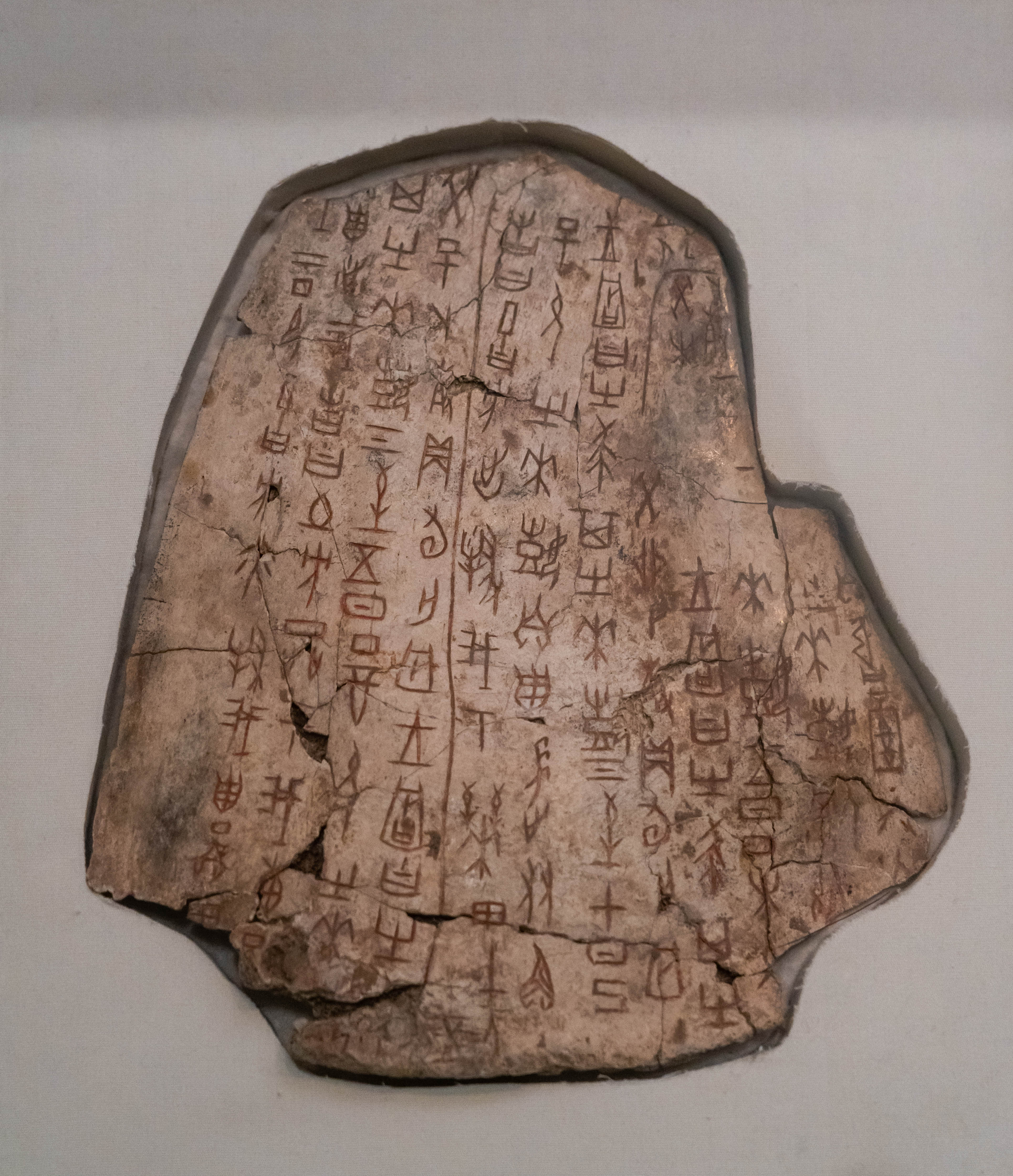

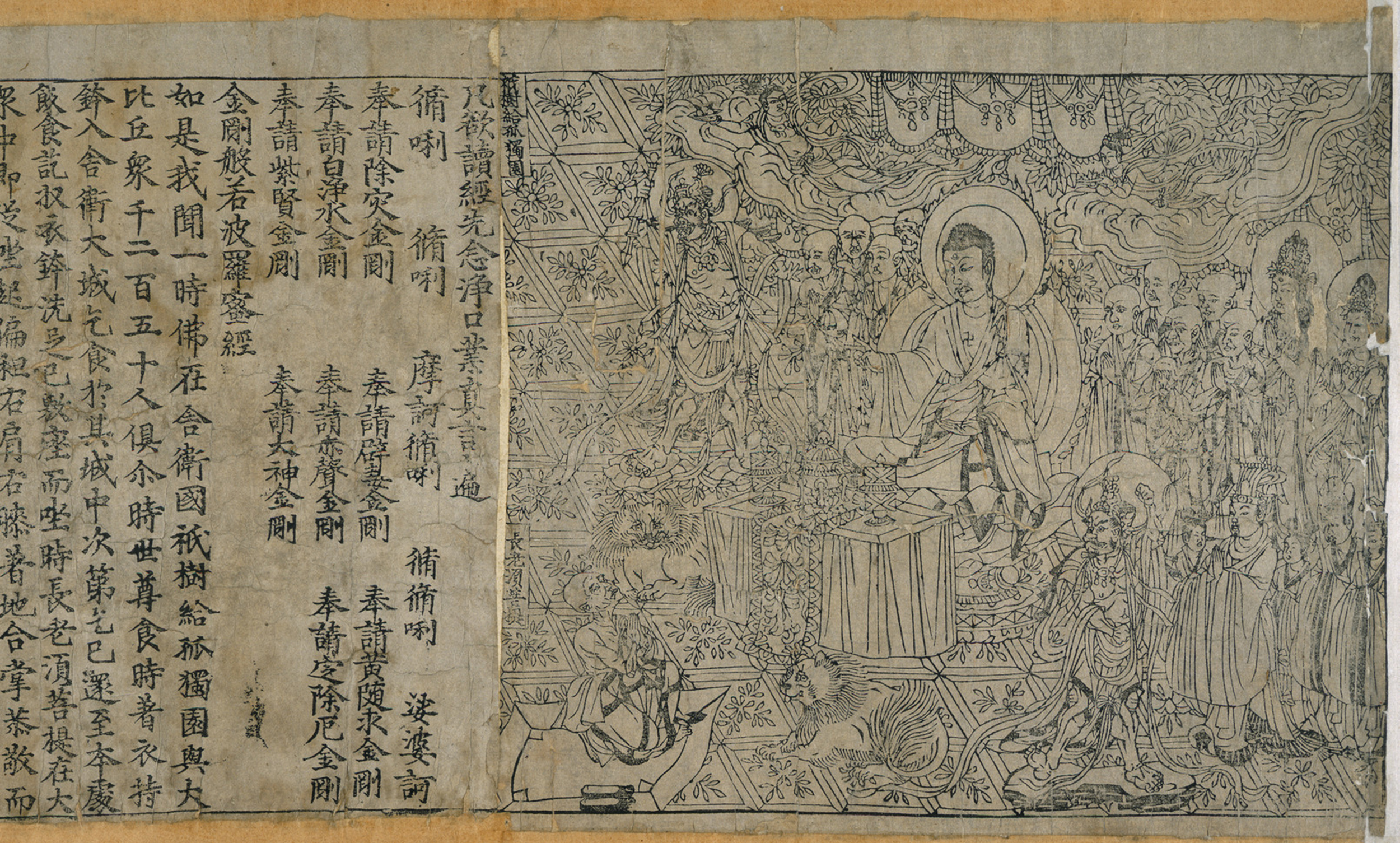

The earliest Chinese literature was inscribed on pieces of bone or turtle shell called oracle bones from about 1500 to 1045 B.C., during the Shang dynasty. These inscriptions recorded the administrative duties, dreams, and future concerns of the royal families. A period of great philosophical activity in the latter part of the Zhou dynasty produced the Confucian, Taoist, and other classic writings. These classics, written in a highly refined script known as wenyan (patterned words), became models of Chinese literature.

For most of Chinese history, poetry was considered the highest form of literary achievement. It was esteemed not only on its own, but also as an important part of dramas, stories, and novels. Poetry was even inscribed on paintings. For more information on China’s rich literary heritage, see Chinese literature.

Painting.

Chinese potters painted sophisticated designs on their vessels as early as the 4000’s B.C. Painting on silk began during the Shang dynasty. Painting on paper began after the Chinese invented paper in the 200’s B.C. Early paintings showed people, animals, spirits, or abstract designs. By the A.D. 900’s, landscapes became the chief subject of Chinese painting. During the Song dynasty (960-1279), many artists painted landscapes showing towering mountains and vast expanses of water. These artworks expressed a harmony between nature and the human spirit.

Chinese calligraphy (fine handwriting) has long been closely linked with the arts of poetry and painting. The use of a brush for writing became common during the Han dynasty (206 B.C.-A.D. 220). The Chinese traditionally considered calligraphy as the highest form of art.

In the A.D. 1000’s, painters began to combine landscapes and other subjects with written inscriptions that added to the overall design. These inscriptions typically described the artist’s feelings about the scene or the circumstances under which the painting was created. Owners of such paintings would often add inscriptions to the work, recording their own reactions.

In traditional Chinese painting, artists use the same kind of brush for painting as for calligraphy. It consists of a wooden or bamboo handle with bristles of animal hair arranged to form an extremely fine point. The artist can paint many kinds of lines by adjusting the angle of the brush and the pressure on it. Chinese artists paint chiefly with black ink made of pine soot and glue. They sometimes use plant or mineral pigments to add color to their paintings. Chinese painters have created many works on paper or silk scrolls, which can be rolled up for storage and safekeeping. Other paintings have been done on plaster walls or on flat pieces of silk or paper. See Painting (Chinese painting).

Bronze and jade.

The earliest Chinese bronzes were highly decorated vessels created for use in rituals during the Shang and Zhou dynasties. Bronze workers cast the vessels in piece molds, clay molds made of separate pieces of baked clay, which had to be destroyed to free the vessels. Art collectors have prized early Chinese bronzes for centuries, valuing them both for their exquisite design and their antiquity.

The Chinese have always held jade in high regard. Their language has many words built on yu, the word for jade. These words often convey notions of beauty, virtue, long life, and purity. The Chinese used various forms of jade in ceremonies, buried it with the dead, displayed it in homes and palaces, and wore it for both decoration and protection. Jade amulets (charms) supposedly provided protection from evil spirits and preserved the owner’s “life force.” The Chinese esteemed jade chimes for their clear and uplifting sound.

Sculpture and pottery.

Most Chinese sculptures are associated with ritual and religion. They often stand as tomb guardians above ground or as burial attendants in or near graves. Since 1974, thousands of earthenware figures of people, horses, and chariots have been discovered near Xi’an in burial pits near the tomb of Shi Huangdi, the first emperor of the Qin dynasty. These figures, the earliest known life-sized Chinese sculptures, date from the late 200’s B.C.

Buddhism reached China from India toward the end of the Han period (206 B.C. to A.D. 220), and sculptors began to turn their skills to the service of this new religion. The Buddhists built temples in or near cities. In rural areas, they hollowed out cliffsides to form chapels. Sculptors decorated the chapels with figures of Buddha and his attendants. Some sculptures were carved from local stone. Others were molded of clay, fired, painted, and glazed. Still other sculptures were cast of bronze and coated with gold. See Sculpture (China).

The Chinese have made pottery since prehistoric times. They began to use the potter’s wheel before 3000 B.C. and produced glazed pottery as early as the 1300’s B.C. The Chinese developed the world’s first porcelain in the A.D. 100’s, during the Han dynasty. They admired porcelain, and wrote many essays and poems about it. Among the most esteemed types of porcelain were “official ware” (guanyao), produced for the emperor’s household; bluish-white qingbai ware; and crackled ge ware.

Other kinds of porcelains were decorated with folk symbols and the bright colors of folk and religious art. Some featured beautifully painted flowers, landscapes, historical scenes, and calligraphic inscriptions. Porcelain dishware and vases produced during the Tang (618-907), Song (960-1279), and Ming dynasties (1368-1644) and the early part of the Qing dynasty (1644-1912) are among the greatest treasures of Chinese art.

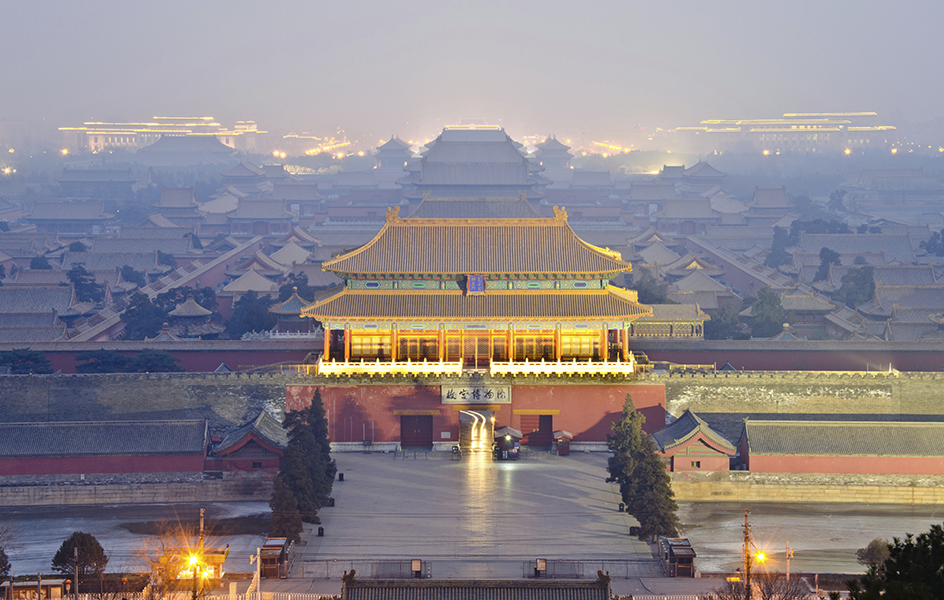

Architecture.

Traditionally, most of the public buildings in China were constructed of wood on a stone or earthen platform. The most outstanding feature of Chinese architecture was a large tile roof with extending edges that curved gracefully upward, a development dating from the Tang dynasty. Wooden columns were connected to the ceiling beams by wooden brackets that branched out to support these roofs. Walls did not carry weight but merely provided privacy. Most buildings had only one story, but the Chinese also built many-storied towers called pagodas (see Pagoda). Today, Chinese architects seldom construct buildings in the traditional styles, and new buildings in Chinese cities look much like those in any modern city.

China’s traditional landscape gardens were designed primarily to serve as Taoist retreats. They combine artistic design, complex symbolism, and careful arrangement. Their structure reflects the interplay between the principles of yin and yang. For example, garden designers place angular buildings among rounded natural features and rock formations next to water. Light areas alternate with dark, and empty spaces with solids.

Music

was extremely important in traditional Chinese society, both for ritual and recreational purposes. The Record of Rites, an ancient Confucian text, states that music is the best way to achieve harmony in the universe. The occasions for music in China ranged from grand public ceremonies and festivals to marriages, funerals, and simple social gatherings.

Loading the player...Chinese ancient ceremonial music

Traditional Chinese music sounds much different from the music of Europe and America because it uses a different scale. The scales most commonly used in Western music have eight tones, but most Chinese scales have five tones. Melody is the most important element in Chinese music. Instruments and voices follow the same melodic line instead of following different lines that harmonize.

Traditional Chinese instruments include the qin, a seven-stringed instrument, and the sheng, a mouth organ made of 17 bamboo pipes. The Chinese also have a lutelike instrument called the pipa and two kinds of flutes, the xiao and the di. Today, Chinese musicians also play non-Chinese instruments and perform the music of many American and European composers, jazz artists, and rock stars.

Theater.

There are several types of Chinese drama: classic zaju (variety performance) of the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368); southern drama (xiwen and chuanqi); various regional styles, such as Kunqu, a form of opera from the region of Suzhou; and a Qing dynasty hybrid form known as jingxi, or Beijing opera. Although each of these traditional dramatic forms has its own special features, all combine spoken language, music, acting, and sometimes mime, dance, or acrobatics.

Chinese drama often uses poetry to convey dramatic mood. Characters that appear frequently in traditional Chinese drama include scholars, military men (both good and bad), heroic women, and silly comic characters. Since the late 1800’s, forms of drama from Europe and the United States have influenced Chinese plays.

The land

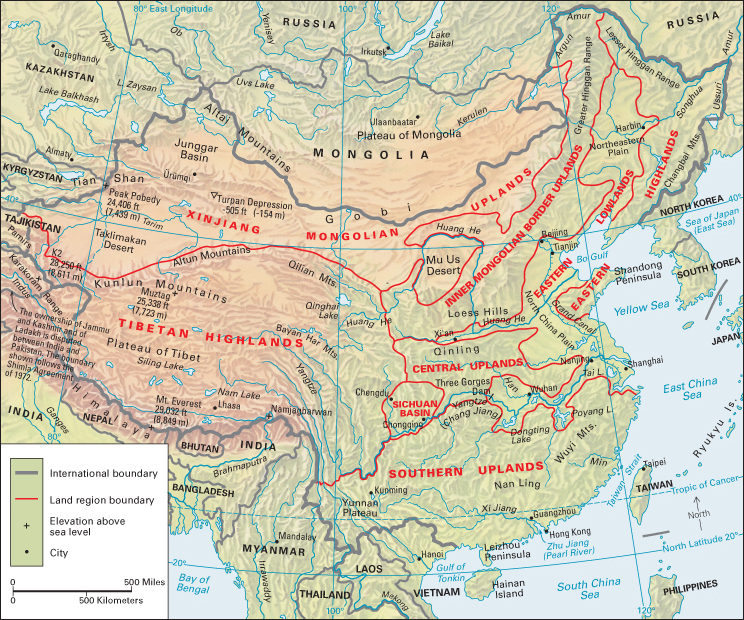

China is the world’s third largest country in area. Only Russia and Canada are larger. China’s land is as varied as it is vast. It ranges from subarctic regions in the north to tropical lowlands in the south, and from fertile plains in the east to deserts in the west.

Northeastern China was once called Manchuria, but today it is called the Northeast (Dongbei in Chinese). Xinjiang covers the far northwest, and Tibet (or Xizang) covers the far southwest. Inner Mongolia lies in the north. The eastern half of China, south of the Northeast and Inner Mongolia, is sometimes called China proper. It has always had most of China’s people.

China can be divided into eight major land regions. They are (1) Tibetan Highlands, (2) Xinjiang-Mongolian Uplands, (3) Inner Mongolian Border Uplands, (4) Eastern Highlands, (5) Eastern Lowlands, (6) Central Uplands, (7) Sichuan Basin, and (8) Southern Uplands.

Much of China is so densely populated that little wildlife remains. However, rugged mountain forests at the eastern edge of the Tibetan Highlands shelter pandas, golden monkeys, takins, and other rare animals. A few elephants and gibbons inhabit the tropical Southern Uplands region. A few Amur, or Siberian, tigers live in remote forests of the Northeast.

The Tibetan Highlands

lie in southwestern China. The region consists of a vast plateau bordered by towering mountains—the Himalaya on the south, the Karakoram Range on the west, and the Kunlun on the north. The world’s highest mountain, Mount Everest, rises 29,032 feet (8,849 meters) above sea level in the Himalaya in southern Tibet. Two of the world’s longest rivers, the Huang He and the Yangtze, begin in the highlands and flow eastward across China to the sea. The Yangtze River is called the Chang Jiang in China.

Tibet suffers from both drought and extreme cold. Most of the region is a wasteland of rock, gravel, snow, and ice. A few areas provide limited grazing for hardy yaks—woolly oxen that furnish food, clothing, and transportation for the Tibetans. Crops grow only in a few lower-lying areas, largely in the east.

The Xinjiang-Mongolian Uplands

occupy the vast dry stretches of northwestern China. The region has plentiful mineral resources. However, it is thinly populated because of its remoteness and harsh climate.

The eastern part of the region consists of two deserts, the Mu Us and part of the Gobi. The western part of the region is divided into two areas by the Tian Shan range, which has peaks over 20,000 feet (6,096 meters) above sea level. South of the mountains lies one of the world’s driest deserts, the Taklimakan. The Turpan Depression, an oasis near the northern edge of the Taklimakan, is the lowest point in China. It lies 505 feet (154 meters) below sea level. To the north of the Tian Shan, the Junggar Basin stretches northward to the Altai Mountains along the Mongolian border.

The Inner Mongolian Border Uplands

lie between the Gobi and the Eastern Lowlands. The Greater Hinggan (also spelled Khingan) Range forms the northern part of the region. The terrain is rugged, and little agriculture is practiced. The southern area is a plateau thickly covered with loess, a fertile, yellowish soil deposited by the wind. Loess consists of tiny mineral particles and is easily worn away. The Huang He and its tributaries have carved out hills and steep-sided valleys in the soft soil. The name Huang He means Yellow River. It comes from the large amounts of silt carried by the river.

The Eastern Highlands

consist of the Shandong Peninsula and the eastern part of the Northeast. The Shandong Peninsula is a hilly region with excellent harbors and rich deposits of coal. The hills of the eastern part of the Northeast have some of China’s best forests. The highest hills are the Changbai Mountains (Long White Mountains) along the border with North Korea. To the north, the Amur River forms the border with Russia. Just south of the Amur is the Lesser Hinggan (also spelled Khingan) Range.

The Eastern Lowlands

lie between the Inner Mongolian Border Uplands and the Eastern Highlands and extend south to the Southern Uplands. From north to south, the region consists of the Northeastern Plain, the North China Plain, and the valley of the Yangtze River. The Eastern Lowlands have China’s best farmland and many of the largest cities.

The Northeastern Plain has fertile soils and large deposits of coal and iron ore. Most of the region’s people live on the southern part of the plain near the Liao River.

Farther south, the wide, flat North China Plain lies in the valley of the Huang He. Wheat is the main crop in this highly productive agricultural area. Major flooding formerly occurred in the valley, which earned the river the nickname China’s Sorrow. Today, dams, dikes, and reservoirs, and the use of river water for irrigation, control most floods. The Grand Canal, the world’s longest artificially created waterway, extends about 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) across the North China Plain.

The lower Yangtze Valley has the best combination of level land, fertile soil, and rainfall anywhere in China. In the so-called Fertile Triangle between Nanjing, Shanghai, and Hangzhou, the population density is extremely high. The Yangtze River and its many tributaries have long formed the most important water route for trade within China.

The Central Uplands

are an area of hills and mountains between the Eastern Lowlands and the Tibetan Highlands. The Qinling mountain range is the region’s chief physical feature. Its peaks rise more than 12,000 feet (3,658 meters) above sea level and cross the region from east to west. The range forms a natural barrier against seasonal winds that carry rain from the south and dust or cold air from the north. To the north of the mountains are dry wheat-growing areas. To the south lie warm, humid areas where rice is the major crop.

The Sichuan Basin,

a large basin surrounded by high mountains, lies southwest of the Central Uplands. Its mild climate and long growing season make it one of China’s main agricultural regions. Most crops are grown on terraced fields—level strips of land cut out of the hillsides. The name Sichuan means Four Rivers and refers to the four streams that flow into the Yangtze River in the region. The rivers have carved out deep gorges in the region’s red sandstone, which makes land travel difficult. The completion of the Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze River allows some ocean-going ships to reach Chongqing in the Sichuan Basin.

The Southern Uplands

cover southeastern China, including the island of Hainan. The Southern Uplands are a region of green hills and mountains. The river deltas of the Xi Jiang (West River) and the Min are almost the only flat areas in the region. The Xi Jiang and its tributaries form the main transportation route for southern China. Deep, rich soils and a tropical climate help make the delta area an extremely productive agricultural region.

Much of the Southern Uplands is so hilly and mountainous that little land can be cultivated, even by terracing. The central part of the region, near the city of Guilin, is one of the most scenic areas in China. It has many isolated limestone hills that rise 100 to 600 feet (30 to 182 meters) almost straight up.

Climate

China has a wide range of climates because it is such a large country and has such a variety of natural features. The most severe climatic conditions occur in the Taklimakan and Gobi deserts. Daytime temperatures in these deserts may exceed 100 °F (38 °C) in summer, but nighttime lows may fall to –30 °F (–34 °C) in winter. Tibet and Heilongjiang province in northeastern China have long, bitterly cold winters. In contrast, coastal areas of southeastern China have a tropical climate.

Seasonal winds called monsoons greatly affect China’s climate. In winter, monsoons carry cold, dry air from central Asia across China toward the sea. These high winds often create dust storms in the north. From late spring to early fall, the monsoons blow from the opposite direction and spread warm, moist air inland from the sea. Because of the monsoons, more rain falls in summer than in winter throughout China. Most parts of the country receive more than 80 percent of their rainfall from May to October.

Summers tend to be hot and humid in southeastern China and in the southern parts of the Northeast. In fact, summer temperatures average about 80 °F (27 °C) throughout much of China. However, northern China has longer and much colder winters than the south has. In January, daily low temperatures average about –13 °F (–25 °C) in Heilongjiang and about 20 °F (–7 °C) throughout much of the eastern third of the country. However, the coastal areas of the Southern uplands are much warmer. Mountains shield southern China and the Yangtze Valley west of Wuhan from the winter winds. The Sichuan Basin is especially well protected, and frost occurs only a few days each winter.

The amount of precipitation varies greatly from region to region in China. The deserts of Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia receive less than 4 inches (10 centimeters) of rain yearly. More than 40 inches (100 centimeters) of rain falls each year in many parts of southeastern China. Some areas near the southeastern coast receive up to 80 inches (200 centimeters) annually. In northern China, the amount of precipitation varies widely from year to year. However, most areas in northern China receive less than 40 inches (100 centimeters) yearly. For example, annual precipitation averages about 25 inches (63 centimeters) in Beijing and 28 inches (70 centimeters) in Shenyang. Snowfalls occur only in the north. But even there, they are infrequent and usually light.

Economy

China has one of the world’s largest economies in terms of its gross domestic product (GDP), the value of all goods and services it produces in a year. In terms of per capita (per person) GDP, however, China ranks near the middle compared to other countries in the world.

The national government exercises much control over China’s economy. It controls the most important industrial plants and operates most of the nation’s banks, most long-distance transportation, and foreign trade. It also sets the prices of certain key goods and services.

China’s Communist government makes national economic plans that cover five-year periods. These plans determine how the government will work to improve different areas of the economy.

In the early 1980’s, the Chinese government began a series of economic reforms that led to less government control over some business activities. Since then, the number of privately owned and operated businesses has increased dramatically. Many experts believe the increased ownership of business has contributed significantly to China’s economic growth. However, it has also led to increased unemployment and labor migration.

In the 1990’s, the government began spending huge amounts of money to improve China’s infrastructure (roads, bridges, dams, and other public works). These projects include the Three Gorges Dam, canals to bring water from the south to the north, and subway systems in major cities.

China’s economy continued to grow in the 2000’s and 2010’s. China became the world’s largest manufacturer. However, the rapid growth led to such problems as pollution and income inequality. By 2020, China’s government had begun to plan a shift in its focus on development, from manufacturing to consumer services and high technology. Planners hoped the resulting growth, though less rapid, would be more sustainable.

Manufacturing and mining

contribute more to China’s GDP than any other category of economic activity. Shanghai is one of the world’s leading manufacturing centers. Its industrial output exceeds that of any other place in China. Beijing and Tianjin are also important industrial centers. Others include Shenyang and Harbin in the Northeast; Guangzhou, Hangzhou, Shenzhen, and Wuhan in southeastern China; and Chengdu and Chongqing in the Sichuan Basin.

After the Communists came to power, they began to rebuild China’s factories in an effort to make the nation an industrial power. They concentrated on the development of heavy industries, such as the production of metals and machinery. Today, China produces more steel than any other country. The machine-building industry provides metalworking tools and other machines for new factories. Other major manufactured products include aircraft, automobiles, cement and other building materials, fertilizer and other chemicals, military equipment, ships, tractors, and trucks.

The largest consumer goods industries include the clothing and textile industry, the food-processing industry, and electronics. As the standard of living in China has improved, demand has grown for such consumer goods as automobiles, refrigerators, and television sets. As a result, China has increased its production of consumer items.

To help continue the country’s industrial expansion, China’s leaders made contracts with foreign companies to modernize factories and to build new ones. The government is also improving and expanding scientific and technical education in China and sending students abroad for training. However, waste and inefficiency in industry remain problems.

China is the world’s largest producer and user of coal. Coal deposits lie in many parts of China, but the best fields are in the north. Coal-burning plants provide about 60 percent of China’s electric energy. Hydroelectric plants and oil-burning plants supply most of the rest. The largest oil field in China is at Daqing in Heilongjiang. Other major Chinese oil fields include those at Dagang, near Tianjin; at Liaohe, in Liaoning; at Shengli on the Shandong Peninsula; in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region; and offshore in the Pacific Ocean.

China is a leading producer of iron ore. Most of the ore comes from large, low-grade deposits in the northeastern provinces. Mines in the central and southwestern parts of the country also yield iron ore.

China outranks all other countries in the production of many mined products, including aluminum, lead, manganese, magnesium, salt, tin, tungsten, and zinc. It is a leading producer of copper, gold, and silver.

Service industries

provide services rather than produce goods. They include banking and finance; communication; education; health care; insurance; recreation; trade; and transportation. Together, they contribute about half of China’s GDP and employ about half of the nation’s workers.

Tourism has become an important part of this economic sector. Each year, tens of millions of tourists visit China from Japan, Russia, South Korea, the United States, and other countries. Tens of millions of Chinese people travel within their country.

Agriculture

contributes less than one tenth of China’s GDP, but it employs approximately a quarter of the nation’s workers. In southeastern and east-central China, farmers grow cotton, rice, sweet potatoes, tea, and wheat. Much corn is grown in the northeast. China produces more apples, cabbages, carrots, cotton, pears, potatoes, rice, sweet potatoes, tea, tobacco, tomatoes, and wheat than any other country. In addition, it is a leading producer of corn, melons, rubber, soybeans, sugar beets, and sugar cane. Farmers in the far south of China grow tropical crops, such as bananas, oranges, and pineapples.

In rural areas, many families raise chickens and ducks. China has more domesticated ducks than any other country. Many farmers raise hogs for both meat and fertilizer. China has about half of all the hogs in the world. China also has many beef and dairy cattle, goats, horses, and sheep.

Only about 15 percent of China’s land area can be cultivated. Thus, farmers have little cropland on which to grow food for themselves and the rest of the country’s huge population. Nevertleless, they manage to provide almost enough food for all the people. Southern China has a long growing season, so farmers there can grow two or more crops on the same land each year. However, droughts and floods often interrupt production. Chinese farmers work mostly by hand with simple tools. They use irrigation and fertilizers and practice soil conservation.

During the 1950’s, the Communists collectivized China’s agriculture. They organized the peasants to farm the land cooperatively in units called communes. In the 1980’s, emphasis on communes declined, and individual families farmed more of the land. The families must pay taxes on their land and must sell an agreed amount of farm products to the state at a fixed price. They may then sell their surplus crops at farm markets, sometimes to city dwellers.

Fishing industry.

China has the world’s largest fishing industry. The Chinese catch tens of millions of tons of fish, shellfish, and other seafood annually. Important catches include anchovies, mackerel, shrimp, and squid. Aquaculture, the commercial raising of animals and plants that live in water, is an important industry in China. China leads the world in aquaculture production. Fish farmers raise fish in ponds both for food and for use in fertilizer. Carp, oysters, scallops, and shrimp are among the leading aquaculture products.

Forestry.

China is a world leader in producing forest products. Its timber industry is concentrated in the southeastern and northeastern parts of the country. But China does not produce enough timber to meet its own needs and must import many forest products.

International trade

is vital to China’s economic development. Foreign investments help China increase its imports and exports. In 1999, China signed a landmark trade agreement with the United States that lowered many barriers to trade. In 2001, China joined the World Trade Organization, a group that promotes international trade. In the following decades, China’s share of international trade grew rapidly. In 2005, it became Japan’s largest trading partner, replacing the United States. China also has extensive trade with the nations of the European Union. However, the United States remains China’s largest individual trading partner. The growing trade deficit of the United States in the 2010’s contributed to economic tension between the world’s two largest economies.

China imports less than it exports. China imports machinery and other technology needed to modernize the economy. Other leading imports include chemicals, metals, and petroleum and petroleum products. China’s main exports include clothing, electronic devices, food, furniture, textiles, and toys. Much of China’s international trade passes through Hong Kong. China’s chief trading partners include Germany, Japan, South Korea, and the United States.

Transportation

in China is a blend of the ultramodern and traditional. For example, Beijing’s Daxing International Airport, which opened in 2019, is an enormous single-terminal airport boasting many unique technological innovations. Yet for movement across short distances, many rural inhabitants still rely on such simple, traditional methods of transportation as animal-drawn carts or on poles carried across their shoulders with loads hanging from them. Bicycles, motor scooters, taxis, and buses also are widely used for local travel. China’s large cities experience frequent traffic gridlock.

Railroads make up the most important part of China’s modern transportation system. Rail lines, including the world’s largest high-speed rail network, link the major cities and manufacturing centers. The railroads transport both freight and passenger traffic.

China has an extensive network of roads that reaches almost every town in the nation. Only the United States and India have more miles of roads. Highway traffic in China consists mostly of trucks and buses. On rural roads, tractors are common. Many cars are owned by government agencies or taxi companies, but growing numbers of Chinese are buying them for personal use.

Ships transport freight, and boats carry passengers and light loads on several Chinese rivers, especially the Yangtze. The Grand Canal, completed about A.D. 1327, extends about 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) from Hangzhou in the south to Beijing in the north. However, silt deposits clog the canal, and only part of it still serves as a water route.

China has many of the world’s largest ports, including Dalian, Guangzhou, Hong Kong, Ningbo-Zhoushan, Qingdao, Shanghai, Tianjin, and Xiamen. The chief airports are at Beijing, Guangzhou, Hong Kong, and Shanghai, but many other cities have airports. Chinese and foreign airlines link China with cities around the world.

Communication

in China comes under strict government control. During the early years of Communism, newspapers, radio, and television were devoted mostly to political propaganda. In the 1980’s, the government began allowing the media to provide general information and entertainment. Educational programs, concerts, plays, and films often appear on television.

Hundreds of newspapers are published in China. The government and the Chinese Communist Party publish or support most of these. One of China’s leading newspapers is Cankao Xiaoxi (Reference News), a paper that contains articles from news sources around the world translated into Chinese. Other leading newspapers include Gongren Ribao (Worker’s Daily); Nanfang Ribao (Southern Daily); Nongmin Ribao (Farmers’ Daily); Renmin Ribao (People’s Daily), the official paper of the Communist Party; and Zhongguo Qingian Bao (China Youth Daily). The Xinhua (New China) News Agency is the nation’s official news agency. Popular online news sites include Xinhua and People’s Daily Online.

In 1978, people in Beijing began to criticize government policies using a kind of poster written in large charcters that had been used in the past to publicize political opinions. These big-character posters began to call for democratic reforms. The wall on which they were hung became known as the Democracy Wall. In 1979, the government forbade posters that criticized its policies. Now, posters typically give such information as tips on health and physical fitness.

Radios and televisions are widespread throughout China, although radio programs are still broadcast over loudspeakers in some rural areas. A village or other group of people sometimes buys a television set and places it in a common area for public use.

In the 1990’s, the telephone system that had been reserved for official purposes was expanded to allow private use. Today, however, cellular telephones are more popular, especially in the cities. By 2012, the number of cell phones in China had already surpassed a billion. People also use the state-run postal system for personal communication.

The internet is popular, but the government tightly regulates its use. Although the government blocks such major foreign sites as Facebook, YouTube, and Google, China is the world’s largest social media market. Popular Chinese social media platforms include Weibo and WeChat. The most popular video sharing site is Douyin, known as TikTok outside of China. Youku hosts television and films. In spite of government monitoring and censorship, some people in China use the internet to express their political views, much as the big-character posters were used in the late 1970’s.

History

The oldest written records of Chinese history date from about 1500 B.C., during the Shang dynasty. These records are in the form of oracle bones—notations scratched on thousands of turtle shells and animal bones. About 100 B.C., the Chinese historian Sima Qian wrote the first major history of China. Through the centuries, the Chinese always kept detailed records of the events of their times.

Beginnings of Chinese civilization.

People lived in what is now China long before the beginning of written history. Early human beings probably inhabited parts of eastern China more than 1 million years ago. Prehistoric human beings known as Homo erectus lived between about 770,000 and 400,000 years ago near what is now Beijing in northern China (see Peking fossils). By about 10,000 B.C., a number of cultures had developed in this area. From two of them—the Yangshao and the Longshan—a distinctly Chinese civilization gradually emerged.

The Yangshao culture reached the peak of its development about 3000 B.C. The culture, which extended from the central valley of the Huang He to the present-day province of Gansu, was based on millet farming. About the same time, the Longshan culture spread over much of what is now the eastern third of the country. The Longshan people lived in walled communities, cultivated rice, and raised cattle and sheep.

The first dynasties.

The Xia culture, which some scholars consider China’s first dynasty, arose during the 2100’s B.C. For many years, experts doubted that the Xia really existed and thought they were only part of Chinese mythology. However, archaeologists found evidence of the culture’s existence in what is now Henan province.

The Shang dynasty arose from the Longshan and Xia cultures. Based on early written records, scholars traditionally dated its start at about 1766 B.C. But now some scholars believe it may have begun about 1600 B.C. The Shang kingdom was centered in the eastern Huang He Valley. It became a highly developed society governed by a hereditary class of aristocrats. The dynasty’s accomplishments included magnificent bronze vessels, horse-drawn war chariots, and a system of writing.

About 1045 B.C., the Zhou people overthrew the Shang from the west and established their own dynasty. The Zhou dynasty ruled China until 256 B.C. The dynasty directly controlled only the western part of their territory. To the east, the Zhou gave authority to certain followers. These followers became lords of semi-independent states. As time passed, these lords grew increasingly independent of the royal court and so weakened its power. In 771 B.C., invaders forced the Zhou to abandon their capital, near what is now Xi’an, and move eastward to Luoyang. Battles between the Zhou rulers and with non-Chinese invaders further weakened the dynasty.

About 500 B.C., the great philosopher Confucius proposed new moral standards to replace the magical practices of his time. During the later Zhou period, there were seven eastern states. The rulers of these states fought one another for the control of all China. In 221 B.C., the Qin state defeated the last of its rival states and established China’s first empire controlled by a strong central government. The Qin believed in a philosophy called Legalism, and their victory resulted partly from following Legalistic ideas. Legalism emphasized the importance of authority, efficient administration, and strict laws. A combination of Legalistic administrative practices and Confucian moral values helped the Chinese empires endure for more than 2,000 years.

The Qin dynasty

lasted only until 206 B.C., but it brought great changes that influenced all later empires in China. The first Qin emperor, Shi Huangdi, abolished the local states and set up a strong central government. His government standardized weights and measures, the currency, and the Chinese writing system. To keep out invaders, he ordered the construction of the Great Wall of China. Laborers built the wall by joining shorter walls constructed during the Zhou dynasty. Parts of the wall were added to, rebuilt, and moved by later dynasties. Much of what is now known as the Great Wall was built during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). This portion of the Great Wall extends from the Bo Gulf of the Yellow Sea to the Jiayu Pass in what is now Gansu province in western China. It stretches about 5,500 miles (8,850 kilometers), including about 3,890 miles (6,260 kilometers) of handmade walls as well as such natural barriers as rivers and hills. Experts believe that the full extent of the Great Wall, including sections predating the Ming dynasty, measures about 13,170 miles (21,200 kilometers).

Shi Huangdi taxed the Chinese people heavily to support his military campaigns and his vast building projects. These taxes and the harsh enforcement of laws led to rebellion and civil war soon after his death in 210 B.C. The Qin dynasty collapsed four years later.

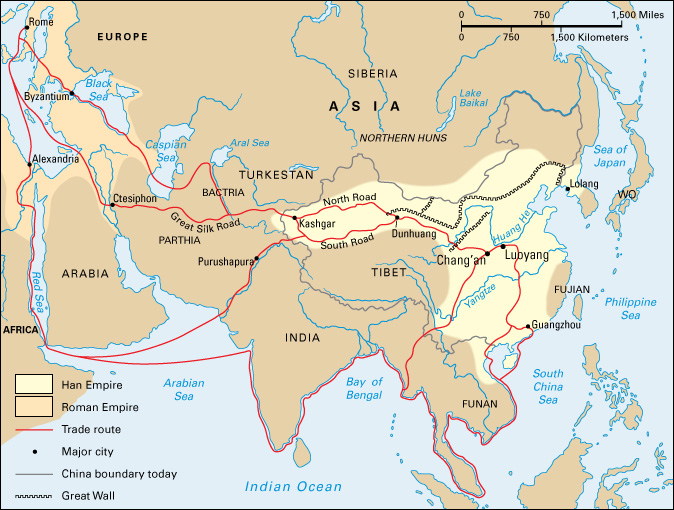

The Han dynasty

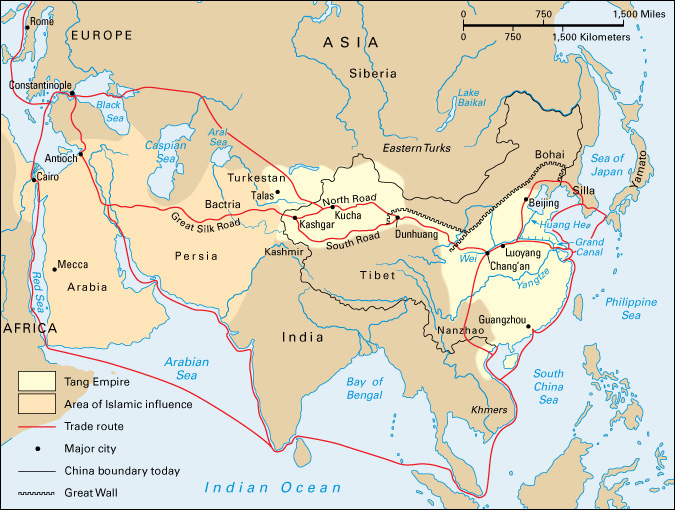

then gained control of China. It ruled from 206 B.C. to A.D. 220. During the Han period, Confucianism became the philosophical basis of government. Aristocrats held most important state offices. However, a person’s qualifications began to play a role in the selection and placement of officials. Chinese influence spread into neighboring countries, and overland trade routes linked China with Europe for the first time.

In A.D. 9, a Han official named Wang Mang seized the throne and set up the Xin dynasty. However, the Han dynasty regained control of China by A.D. 25. Art, education, and science thrived. Writers produced histories and dictionaries. They also collected classics of literature from earlier times. During the late Han period, Buddhism was introduced into China from India.

Political struggles at the royal court and administrative dishonesty plagued the last century of Han rule. In addition, powerful regional officials began to mistreat the peasants. As a result, large-scale rebellion finally broke out, and the Han dynasty fell in 220.

The period of division.

China then split into three competing kingdoms. Soon afterward, nomadic groups invaded northern China. A series of Chinese and non-Chinese dynasties ruled all or part of the north from 304 to 581. Six dynasties followed one another in the south from 222 to 589. During this period of division, Buddhism spread across China and influenced all aspects of life.

The brief Sui dynasty (581-618) reunified China when it absorbed the last southern dynasty in 589. By 610, the Grand Canal linked the Yangtze Valley with northern China. The canal made the grain and other products of the south more easily available to support the political and military needs of the north.

The Tang dynasty

replaced the Sui in 618 and ruled China for nearly 300 years. The Tang period was an age of prosperity and great cultural accomplishment. The Tang capital at Chang’an (now Xi’an) had more than a million people, making it the largest city in the world. It attracted diplomats, traders, poets, and scholars from throughout Asia. Some of China’s greatest poets, including Li Bo and Du Fu, wrote during the Tang period. Buddhism, in forms adapted to Chinese ways, remained an enormous cultural influence. Distinctly Chinese schools of Buddhism spread, including Chan (Zen) and Qingtu (Pure Land). In 690, the emperor’s mother, Wu Zetian, seized the throne and became the only woman in Chinese history to rule in her own name. Empress Wu was an able but ruthless ruler. She was overthrown in 705.

In 755, a rebellion led by a northern general named An Lushan touched off a gradual decline in Tang power. A series of rebellions in the late 800’s further weakened the Tang empire, which finally ended in 907. During the period that followed, a succession of “Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms” struggled for control of the empire. In 960, the Song dynasty reunified China.

The Song dynasty

brought major changes that affected China throughout the remaining empires. The Song rulers firmly established a system of civil service examinations that had begun during the Han period. They thus completed the shift of social and political power from aristocratic families to officials selected on the basis of talent. Another significant change was the development of Neo-Confucianism, which combined the moral standards of traditional Confucianism with elements of Buddhism and Taoism. The philosopher Zhu Xi was largely responsible for this new Confucianism. The Song dynasty established Neo-Confucianism as the official state philosophy, and all later Chinese dynasties continued to support it.

During the Song period, the introduction of early ripening rice made it possible to grow two or three crops a year in the south. The increased rice production helped lead to and support a rapid growth in the population, which for the first time exceeded 100 million. Chinese inventions during this period included a handheld gun and movable type for printing. Literature, philosophy, and history flourished. In the fine arts, the great Song achievements were hard-glazed porcelains and magnificent landscape paintings.

The Song dynasty suffered from frequent attacks by nomadic peoples from the north. By 1127, it had lost its hold in northern China to a rival dynasty from northeastern China. The Song then moved their capital from Kaifeng to Hangzhou on the wealthy lower Yangtze Delta. The dynasty that ruled from 960 to 1127 is often called the Northern Song, and the dynasty that ruled after 1127 is called the Southern Song.

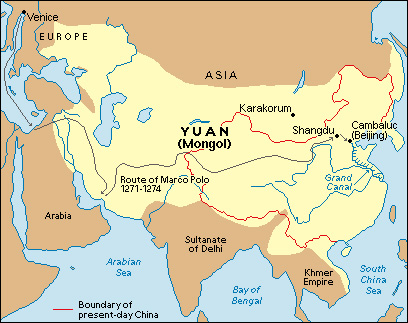

Mongol rule.

During the 1200’s, Mongol warriors swept into China from the north. The Mongol leader Kublai Khan established the Yuan dynasty. It controlled all of China from 1279 to 1368, the first time that the entire country had come under foreign rule. During the Yuan period, Europeans became increasingly interested in China because of the reports of travelers and traders. The most enthusiastic reports came from Marco Polo, a trader from Venice. He claimed that he traveled widely in China from 1275 to 1292, and he gave glowing accounts of the highly civilized country known by Europeans as Cathay.

The Mongols ruled China harshly. During the mid-1300’s, rebellions drove the Mongols out of China and led to the establishment of the Ming dynasty.

The Ming dynasty

ruled from 1368 to 1644, a period of stability, prosperity, and revived Chinese influence in eastern Asia. Ming fleets—the largest the world had ever seen—sailed through Southeast Asia to Arabia and eastern Africa, projecting the power of the Ming court. Ming armies fought to extend and protect Chinese influence in Vietnam, Mongolia, and Korea. The arts flourished again. The era’s literature included three of China’s great classical novels—Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Water Margin, and Journey to the West. The Ming rulers distrusted the European traders who visited China in the late 1500’s and the 1600’s, but they allowed Roman Catholic missionaries to serve at court because of the missionaries’ skill in astronomy. Though also viewed with suspicion, the missionaries succeeded in converting some influential Chinese officials.

The early rule of the Manchus.

In 1644, the Manchus from northeastern China invaded Beijing, the Ming capital, and established the Qing dynasty. The Manchus ruled China until 1912. Like the Mongols, the Manchus came from beyond the Great Wall. Unlike the Mongols, the Manchus had adopted many elements of Chinese culture before they gained control of the empire. The Manchus strongly supported Neo-Confucianism and modeled their political system after that of the Ming.

From 1669 to 1796, the Qing empire prospered. Chinese influence extended into Mongolia, Tibet, and other parts of central Asia. Commerce and the handicraft industry built up the economy. Agricultural output increased as China’s population expanded rapidly, doubling from about 150 million in 1700 to about 300 million by 1800.

By the late 1700’s, the standard of living in China began to decline as the population grew faster than agricultural production. In the 1770’s, political dishonesty began to plague the Qing administration. In 1796, the worsening conditions touched off a rebellion, led by an anti-Manchu secret society. The rebellion lasted until 1804 and greatly weakened the Qing dynasty.

The dynastic cycle.

Chinese historians noticed a pattern to the rise and fall of China’s dynasties. They saw that dynasties usually began with a strong ruler who established an empire, often using ruthless means. Once established, the dynasty would expand and make great contributions to Chinese culture. Later rulers would become corrupt and neglect the empire, which eventually would weaken and fall after a rebellion. From the chaos that followed, a new strong leader would emerge, and the cycle would begin again.

Many Chinese people believed the cyclic pattern could help them predict what would happen next to a dynasty. Peasants added the idea that natural events, such as earthquakes, were signs that things were about to change. These ideas continue to influence Chinese thought today.

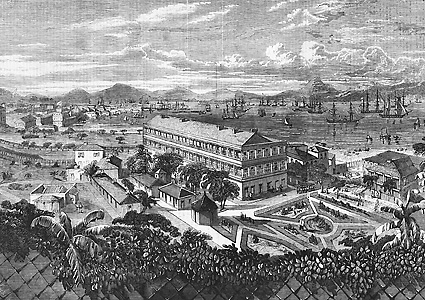

Clash with the Western powers.