City planning is a process for guiding the development of cities and towns. City planners—the people who direct the process—advise local governments on ways to improve communities. They also advise governments and real estate developers who are planning entirely new neighborhoods and communities. This article deals primarily with city planning as it is carried out in the United States and many other Western countries.

City planners deal with the physical layout of communities, the mix of housing, shopping, and industrial areas, and the location of such services as sewers, roads, and parks. They make proposals designed to beautify communities and to make life in them comfortable, enjoyable, and profitable. Their proposals include creating affordable housing, preserving open space and parks, and improving transit and roads.

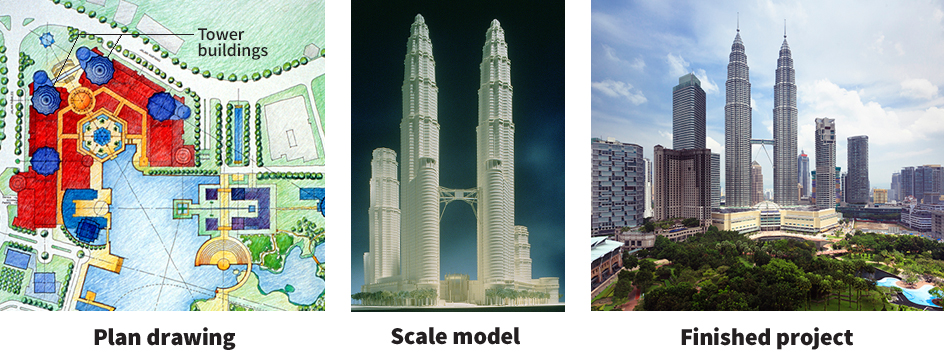

Many city planners work for local governments. Others work for developers or groups of citizens who propose plans to the government. A city planner’s day-to-day work often involves working with community members to coordinate improvements in parts of a community. But a planner views a community as a single system in which all the parts are dependent on one another. A planner may create a comprehensive plan (overall plan) and use it as the basis for coordinating public and private decisions for using land. Such a plan shows the entire community both as it is and as the community envisions it should be. The city planner’s suggestions for changes in any part of a community should follow the comprehensive plan. For example, the plan might restrict the height of buildings in residential areas. City planners then apply this restriction whenever they review any proposal for residential development.

City planners try to predict the future. They attempt to forecast changes in population, employment, and industrial activity over periods of 5, 10, or even 20 to 50 years into the future. The predictions of city planners help a government and the private sector plan for the future. The private sector includes all businesses owned by private individuals or groups.

City planning began with the first cities—about 3500 B.C. Ancient peoples set aside areas for housing, worship, and other activities. They built walls around their communities for protection against enemies. Throughout history, people have done some planning for their communities. But planning has not kept pace with the tremendous growth of urban communities. Many became especially dirty, noisy, overcrowded, and run-down in the 1800’s during the Industrial Revolution. In the early 1900’s, the profession of city planning arose to help to more systematically redevelop such communities and to manage new development in places that are rapidly growing. Since then, governments have greatly increased city planning activities in an attempt to help solve the many problems of cities and towns. For a discussion of these problems, see the article City (Future cities).

The comprehensive plan

Leading the process that prepares a comprehensive plan ranks among the most important duties of a city planner. A comprehensive plan, also called a master plan or general plan, includes data, maps, and models that show a community as it is and long-term goals and visions of the community as community members believe it should exist in the future. The plan includes proposals for policies, programs, and projects that will help achieve the community’s vision and goals.

A comprehensive plan shows how land should be used. It also shows how public facilities and services—such as schools, roads, fire and police stations, and water, sewerage, and transportation systems—should be improved or expanded. Planners call these services and facilities a community’s infrastructure. In some cities, new developments are permitted only when a comprehensive plan allows the developments and when the infrastructure can provide certain levels of expanded service. In some states of the United States, as well as in some other countries, a comprehensive plan is required by state or local authorities before a city can proceed with development.

Preparing the plan.

A professional city planner consults members of the general public and many professional experts in preparing a comprehensive plan. Throughout the process, the city planner works with members of the public who will be affected by the plan. These people include business persons, homeowners, and community groups. The general public should play a critical role in the preparation of the plan. Professional experts might include architects, economists, educators, engineers, finance specialists, geographers, lawyers, political scientists, statisticians, and specialists in air and water quality. They provide expert analysis and advice on specialized issues addressed in a plan.

Today, many city planners use a variety of computer programs and Internet resources in their work. Planners also use computers to collect and analyze data about community conditions, to create maps and designs, and, increasingly, to allow the public to provide input.

Some communities hire a private planning firm that coordinates the process of preparing a comprehensive plan and guides its approval by the local government. In many other communities, an agency of the local government is responsible for planning activities. Often the local government includes a department of city planning or development, which may also be responsible for inspecting buildings. (Building inspections help to ensure that structures are safe and suited to their intended purpose.) This department leads the process for preparing the comprehensive plan, as well as other specialized plans like transportation, disaster, housing, and climate change plans. The city planner and other department members are responsible to the top executive.

Proposals of the plan.

A comprehensive plan aims to make community life more comfortable, enjoyable, safe, and profitable. A good plan provides transportation facilities that enable people to get to and from stores, offices, and factories quickly and easily. It also provides enough recreation areas, schools, and shopping facilities.

The major part of a comprehensive plan recommends how the community’s land should be used. The plan divides the community into sections. It classifies some sections as residential areas, others as commercial and industrial areas, and the rest as public facility sites. Increasingly, plans call for mixed-use sections with a combination of residences, businesses, and public facilities. Plans divide these major sections into smaller districts, each with certain building restrictions. For example, the plan reserves some parts of residential areas for houses only and some for both houses and small apartment buildings. It may propose construction of high-rise apartment buildings in other neighborhoods. The comprehensive plan may permit retail trade, wholesale trade, and light manufacturing in some commercial and industrial districts but forbid heavy manufacturing there.

A comprehensive plan may suggest ways to improve the appearance of a community. For example, it may propose treelined boulevards, parks, and a new civic center. Such improvements are sometimes called urban design.

The plan may include proposals for major changes in citywide facilities, such as sanitation and transportation systems. It may recommend a more complex sanitary drainage system for heavy manufacturing areas than for residential and commercial districts. The plan also may call for such developments as the widening of streets and the construction of a new commuter rail or bus route to ease travel between residential, commercial, and industrial areas.

City planners are still chiefly concerned with the physical layout of communities. But since the mid-1900’s, many planners have also dealt with economic and social problems. Today, a city plan may include proposals for economic development, education, health care, reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, and social programs for disadvantaged residents. Most scientists believe that greenhouse gas emissions contribute to global warming. See the article Global warming (Causes of global warming).

Making city planning work

City planners need both money and authority to carry out their programs. They get much of the money from local and federal governments. But governments get their money by taxing the people, so much of the money a city planner uses actually comes from the people. Local; state, provincial, or territorial; and federal governments may give city planners the authority they need to carry out their plans, but ultimate authority rests with elected officials and the courts.

Gaining support for the plan.

Strong public opposition can cause a government to refuse to act on proposals of a comprehensive plan. Proposals may lose support if the public believes they are too costly or would benefit only a small part of the population.

City planners are likely to gain public support by involving the public throughout the planning process and by developing proposals that capture the imagination of the people. Such proposals include the development of housing, office buildings, and other facilities that can make a city more enjoyable. Sometimes a plan gains public support because it includes proposals for solving problems of deep concern to most of the people. For example, a proposal to improve a combination of roads and transit service may get wide support in a community that constantly has bad traffic jams.

Governmental authority.

To carry out their plans, city planners must have influence over development and other activities that affect the layout of a community. They rely on the government’s authority to enforce zoning laws, subdivision regulations, and building and housing codes and, sometimes, on the power of eminent domain or other similar powers.

The term eminent domain in the United States describes a government’s right to buy (at a fair price) private property—even when the owner does not want to sell it. Similar power is referred to as resumption, compulsory acquisition, expropriation, or compulsory purchase in other nations. City planners must often rely on this power to get the land they need for major rebuilding projects. In the United States and nearly all other countries, governments have used eminent domain to carry out urban redevelopment programs and to build roads and other parts of a community’s infrastructure. See Eminent domain; Urban renewal.

Zoning laws designate the kinds of buildings permitted in each part of a community. If a zoning law allows only houses and apartment buildings in a certain area, city planners know they can plan that area as completely residential. Zoning laws also allow planners to regulate sizes of lots (sections of land), heights of buildings, the number and location of parking and loading areas, and the use of signs. See Zoning.

Other regulations control the subdivision and development of large, open land areas. Private real estate developers often buy large areas and subdivide them into lots. They either sell the empty lots or construct buildings on the lots before selling. Subdivision regulations designate the size of lots and other aspects of physical layout. For example, they cover the location and width of streets and the amount of land that must be used for public buildings, schools, and open space.

Building and housing codes regulate the safety and quality of construction. They also include rules that govern the number of occupants per building and the quality of electric wiring and plumbing.

Building new communities

The term city planning usually refers to attempts to improve existing communities. But it can also mean the development of entirely new communities. These communities, called new cities and new towns, differ from suburbs in at least one important way. Most suburbs are designed chiefly as residential communities for people who work in nearby cities. Planners of new communities try to make them fully or partly self-supporting by attracting businesses, thus providing places for the residents to work.

New cities and new towns differ from one another in location and in the degree to which they are self-supporting. Planners of new cities try to ensure that the communities have enough facilities and job opportunities for all the residents. Thus, new cities can be built far from existing cities. In the mid-1900’s, the Brazilian government built Brazil’s new capital, Brasília, far from the country’s population center. New cities are extremely costly projects. Brasília and Canberra, Australia, are among the few ever completed in Western nations since World War II (1939-1945).

New towns provide jobs for many of their residents, but most rely on neighboring cities for many jobs. Most new towns are built within commuting distance of a big city. Others are communities within such a city.

During the mid-1900’s, the United Kingdom and the Scandinavian countries ranked among the leaders in the development of new towns. The governments of these nations provided aid for new town development, including money and the authority to purchase the needed land. In the United States, private business is the major source of funds for new town development. But the development of a new town is a slow, costly process, and many private developers are reluctant to take on such a project.

In the early 2000’s, new cities were primarily being built in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, though in Africa and Latin America, they were modest in number. New cities included Ciudad Caribia in Venezuela, Kilamba New City in Angola, and Appolonia City of Light and King City in Ghana. In Asia, it is estimated that hundreds of new cities are being planned in China and India alone. As many as two dozen new cities a year are being constructed in China, including such mega cities as Kangbashi in the Ordos region of Inner Mongolia and Yujiapu, near Tianjin, which is modeled after New York City’s Manhattan Island. Another new city, Songdo in South Korea, was designed as a “smart” or high-tech city with 40 percent green space. Green space is an area that includes such natural features as grass and trees that have been set aside in an urban environment. However, many of these new cities have few inhabitants, largely due to the high cost of housing, unfavorable locations, and other concerns.

Criticism of city planning

Although most people favor the goals of city planning, some criticize the methods used to achieve those goals. Major criticisms include the length of time needed to implement plans, the high cost of planning, government control of city planning, and what opponents feel is a wrong emphasis on certain goals.

Length of time

required for city planning is a common criticism. Some political leaders argue that the results of city planning often come too late to solve the problems that the planning was intended to address. Some private developers believe that planning causes delays that result in higher costs.

High cost

is another common criticism of city planning. Critics claim that the cost of developing and carrying out a comprehensive plan places too great a burden on the taxpayers. They argue that city planners try to do too much at one time.

Government control.

Some people object to a government’s power to regulate the use of private property and to force individuals to sell their property. They view this power as a violation of owners’ rights. Some people also object to the city planner’s role as a decision maker because the planner is not an elected official.

Wrong emphasis.

Some critics complain that city planners care more about beautifying communities and helping businesses than about solving such social problems as overcrowding and pollution. These critics also charge that changes made for a community’s physical improvement sometimes increase the social problems. For example, a loss of low-cost housing results when luxury apartments replace run-down buildings.

Some people believe that city planners put too much emphasis on the future of cities and towns and not enough on present problems. Yet others criticize city planners who assist in trying to solve day-to-day problems. They believe that planners should concentrate on long-range programs because the planners are the officials most directly concerned with the future development of communities.

Reducing criticism.

City planners serve the public interest, and so they work to engage the public. More and more cities are scheduling planning projects farther and farther apart to reduce the financial burden on taxpayers and developers. Planners also hope that more and more people will become convinced of the value of city planning as they see the completed projects.

History of city planning

People have done some city planning ever since the first cities appeared about 3500 B.C. This section traces some of the highlights of city planning. For a detailed description of cities and their development through the ages, see City.

Ancient times.

People of ancient cities set aside certain areas for meetings, recreation, trade, and worship. Many ancient peoples built walls around their cities to keep invaders out. Groups of public buildings and monuments are among the major examples of city planning in ancient times. Athens, Greece, and Rome, Italy, were especially famous for their public buildings and monuments.

Historians believe that Hippodamus, an ancient Greek architect, developed the first systematic theories about city planning. His work probably included plans for the use of land and the location of streets and buildings in the cities of Miletus and Piraeus.

The Middle Ages.

Many peoples built protective walls around their cities during the Middle Ages—from about the A.D. 400’s through the 1400’s. Population growth caused a number of cities to become overcrowded. Some cities solved this problem by knocking down the walls. Other cities let the walls stand and built new cities nearby. Religion played a major role in medieval European life and was reflected in the planning of many cities. The main church stood in the center of the city and was the biggest and most expensive building.

The Renaissance,

a period of great artistic development, began near the end of the Middle Ages and lasted into the 1600’s. Several leading artists of the Renaissance, including Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Leonardo da Vinci, and Michelangelo, helped beautify cities.

During the Renaissance and for many years after it, city planners designed parts of cities on a grand scale. They created open spaces to overcome the overcrowding of earlier days. Examples of this trend include the huge plazas in front of the Cathedral of Saint Mark in Venice and Saint Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City. Another is the beautiful palace and gardens at Versailles, near Paris. Perhaps the high point of the trend toward city planning on a grand scale was Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s plan for Paris in the mid-1800’s. Haussmann designed wide boulevards and plazas and helped make Paris one of the world’s most beautiful cities. However, his modernization of Paris affected an estimated 60 percent of the city’s buildings. Some 20,000 buildings, in some cases entire medieval neighborhoods, were destroyed, and thousands of people were displaced.

In colonial America, most cities and towns were smaller and less elaborate than the European communities. Early planned cities included Charleston, South Carolina; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Savannah, Georgia; and Washington, D.C. Washington was probably the most elaborately planned early American city. George Washington hired Pierre Charles L’Enfant, a French architect, to plan it.

The Industrial Revolution

of the 1700’s and early 1800’s marked the beginning of the factory system of manufacturing. In Europe and North America, the population of many cities increased rapidly as thousands of workers left farms to take manufacturing jobs in cities. Cities became overcrowded, dirty, and noisy. Many people lived in crowded, run-down, unsanitary housing near the factories.

Social reformers began calling on governments to improve city life. They proposed new housing areas with gardens and open spaces and new communities with industry and housing in separate areas. Governments took some steps to regulate the quality of housing and to otherwise improve cities. But the cities continued to grow, and city planning failed to keep pace.

Planners tried to show what the ideal city could look like at the World’s Columbian Exposition, held in Chicago in 1893. American architect Daniel Burnham planned and arranged most of the buildings at the exposition, which marked the beginning of the City Beautiful movement in the United States. Plans influenced by the movement were characterized by wide boulevards, spacious parks, and large, graceful public buildings.

The 1900’s.

Until the early 1900’s, city planning in the United States was largely the responsibility of architects who were hired by private organizations or, in some cases, by governments. The rapid increase in urban problems during the late 1800’s forced governments to take a greater part in city planning.

From 1900 to 1930, many local governments in the United States established city planning commissions and introduced zoning laws. Among the most famous redevelopment plans of the early 1900’s was Burnham’s Plan for Chicago, which reflected the style of the City Beautiful movement. The urban population explosion that followed World War II (1939-1945) and policies that favored suburban development over reinvesting in urban neighborhoods caused severe housing shortages, deteriorating neighborhoods, and heavier traffic than ever. To meet the challenge of growing cities, planning agencies had to expand their programs to provide for new housing projects, highways, parks and recreation areas, and better industrial and commercial districts.

In the cities of Europe, including those in the United Kingdom, destruction caused by World War II made rebuilding a priority. In Australia, in the decades after the war, the national government created public housing development, while state governments built new suburbs near state capitals. Some projects created controversy, however, for their large size and destruction of existing neighborhoods. In some countries, such as France and the Netherlands, city planning in the late 1900’s and early 2000’s was largely controlled by strong national governments rather than local authorities.

Early 2000’s.

Today, city planning in many countries is usually done by a partnership of government planning agencies and private developers. In the United States, for example, such partnerships have redeveloped many run-down urban areas, including Faneuil Hall Marketplace in Boston, South Street Seaport in New York City, and Harborplace in Baltimore.