Clothing refers to the different items that people have worn in different cultures throughout human history. Like food and shelter, clothing is one of people’s most important needs. Many things—including geography, politics, trade, and religion—influence clothing choices.

Clothing has two main functions, protection and identity. It can protect the wearer physically and symbolically. For example, warm clothing can protect people from the cold. People might also believe that certain decorations or symbols on a garment can shield the wearer from harm. Clothing can also reveal social identity and status—that is, a person’s social position within a society. For example, a tribal chieftain might wear a large robe to indicate his wealth and rank. Clothing choices reflect who a person is.

Each culture has a different standard of beauty, and clothing can help a person achieve that standard. People like to decorate themselves, and they often use clothing and accessories to do so.

Sources of information about clothing of the past depend on the culture that created the clothing. Perhaps the best sources are surviving examples of clothing. Other sources can include works of art made at the same time as the clothing and evidence from archaeology (the study of the people, customs, and life of ancient times). Diaries, letters, bills of sale, and other documents that describe clothing can also provide information. For example, most of what scholars know about ancient Greek costume comes from ancient writings and from works of art found in archaeological excavations. The more recent the clothing, the more sources exist to study and the more scholars can learn about it.

Much of what we know about historic dress comes from the apparel of the elite—the upper class in a given society. The rulers, court attendants, and other individuals of wealth and status had the money to have their portraits painted and their garments preserved. In contrast, the majority of the population wore their clothing until it became rags. Throughout most of recorded history, only those with the money to frequently replace their garments indulged in changing fashions.

Why people wear clothing

Throughout the world, clothing serves many functions. These functions can generally be grouped into two main purposes, protection and identity.

Protection.

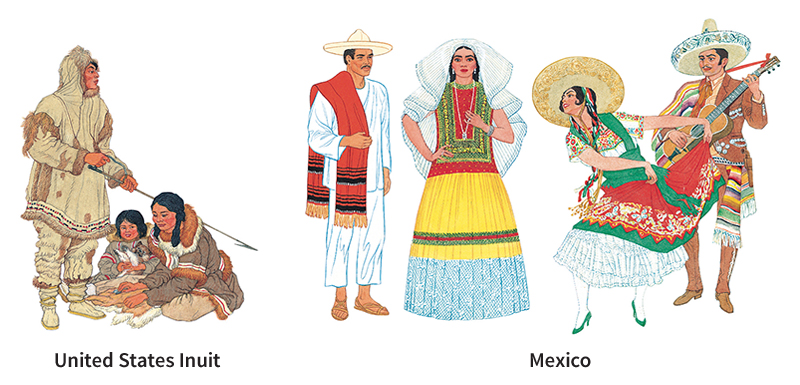

Clothing helps protect people from harm in both physical and symbolic ways. Early humans probably first started wearing clothes to protect themselves from the elements and survive in cold temperatures. For example, Neandertal people, who lived in Europe and central Asia during the ice age about 150,000 to 39,000 years ago, used bone awls (sharp-pointed tools) to poke holes in animal hides. Then they sewed the hides together into fitted clothing and footwear. The Inuit people of the Arctic traditionally dressed in elaborately tailored fur clothing. People who live in Arctic regions today still need special apparel to protect them from the cold.

People need clothing for protection not only against cold but also against other kinds of weather. In tropical regions, people wear protective headgear to shield them from heavy rains. In deserts, garments that cover the entire body protect their wearers from the variable weather. For example, inhabitants of the Arabian deserts wear loose, flowing garments that shield their bodies from the hot sun and sandstorms that whip against the skin. The same garments protect them against the cold night air.

In warm climates, people make clothes of lightweight materials, such as cotton or linen, which have a loose or open weave. These materials absorb perspiration and allow air to flow around the body. People in these climates also wear white or light-colored clothes because such colors reflect the sun’s rays. Large hats serve as sunshades.

Clothing protects people who work on dangerous jobs, take part in physical sports, or engage in other hazardous activities. For example, a soldier in combat may wear a helmet made of hard material and a vest lined with bullet-resistant fabric. Welders wear protective clothing and shields over their faces. Factory workers cover their mouths and noses to protect their lungs and wear heavy shoes to shield their feet. Football players and some other athletes have padded equipment to guard against injury.

Clothing also protects people in at least two symbolic ways. First, it can keep people safe because it identifies them as members of groups. This membership can protect people in times of social conflict. For example, during the French Revolution (1789-1799), revolutionaries often identified members of the upper class by their fancy clothes and then executed them. Lower-class people in plain clothing escaped death. Muslim women in many societies wear a burqa (also spelled burka) when out in public. This tentlike garment covers almost all of a woman’s face and body. Wearing a burqa signals a woman’s devotion to Islam.

Another way that clothing can provide symbolic protection is if people believe in the protective power of the designs or materials used. In some societies, people believe that evil spirits or spiritual forces can cause them harm. People in these societies may wear special clothes that they think will protect them. Many people throughout the world, for example, believe in the evil eye. A look from an envious person can cause illness or even death. To avoid such harm, people wear amulets (small charms) to guard against the evil eye.

Identity.

Clothing serves to communicate people’s identity in two ways. It signifies membership in groups, and it distinguishes members within groups.

People in all societies belong to many groups at the same time. Everyone belongs to groups based on what social scientists call their ascribed (assigned) statuses. Examples of ascribed statuses include gender, age, and race. Some societies have other categories of ascribed statuses, such as clans or castes (social classes from birth). Clothing often identifies a person’s ascribed statuses.

For example, many women in India wear a sari. This garment consists of a length of cloth about 6 yards (5.5 meters) long draped around the body as a long dress. Within India, a sari may signal woman’s caste and regional origin. In the Tamil Nadu region of India, for example, female members of the Brahmin caste wear their saris in a special way called madisar. Folding the sari in this way requires an additional 2 yards (1.8 meters) of cloth. Women in other castes wrap their saris differently.

As people go through life, their status may change due to their own actions or things that happen to them. Scholars call these changes achieved statuses. Ceremonies often mark a person’s entry into a new stage of life. For example, marriage is an achieved status. All societies have some kind of wedding ceremony. People usually dress in special clothing during the ceremony. Many groups have special clothes to indicate whether a person is married or not. In the United States and Europe, the wedding ring serves this function for both men and women. Among the Kikuyu people of Kenya, the type of belt a woman wears indicates to others whether she is married or single.

Subcultures make up another example of an achieved status group. Subcultures are groups within a larger society that develop cultural patterns which set them apart. Members of various subcultures often use clothing to identify their membership. These subcultures include religious groups and street gangs.

Uniforms rank as one of the most effective ways to identify group membership and achieved status. Members of the police and the military dress in uniforms. Priests may have special garments that they wear only after taking religious vows. Within groups, items of clothing may mark rank. Boy Scouts, for example, receive badges for achieving various skills. Those with more badges have higher rank.

Sometimes an achieved status involves unpleasant circumstances. For example, people who break the law may achieve the status of prisoner and have to put on prison uniforms. People who get sick or have an accident may achieve the status of hospital patient and have to wear a hospital gown.

Clothing also indicates how people within groups differ from one another. Garments communicate different messages depending on the size of the group. At the largest group size—that of all humanity—clothing indicates national and ethnic groups.

Such statuses as class, ethnicity, and nationality can be either ascribed or achieved. All people are born into ethnic and national groups. But they may change these group identities throughout their lives. People’s national identity in their country of origin may become their ethnic identity when they move to another country. In both cases, a person may choose to express his or her ethnicity by wearing traditional ethnic dress.

People both express themselves through dress and understand the meaning of dress in others. People usually consider the groups to which they belong when choosing clothing. They often make this choice without conscious thought. When shopping, a person might choose colors that will fit in with people in their work environment. For example, businessmen shopping for suits in London, Tokyo, or New York City might choose gray, navy, or black. However, a woman in urban South Africa might find bright colors suitable for work. These shoppers intuitively choose the colors that will not stand out from their groups.

Clothing as communication

People can send powerful messages through dress to other people. However, they must be careful to use the symbols understood by their audiences because symbols have different meanings in different societies. For example, in the United States and Europe, people often wear black clothing while mourning the dead. In much of Asia, however, white symbolizes mourning.

People often assign their own cultures’ meanings to the clothing they see and wear. The closer an observer is to the culture of the dress style, the more he or she will notice small differences. On the other hand, the farther the observer is separated from the culture, the more the styles will appear the same. American women may think that all Indian saris look basically alike. However, Indian women easily perceive minor differences in the fabrics, designs, and colors.

Costume designers for theater and dance use clothing to communicate messages about the characters. They choose clothing symbols that they know their audiences will understand. In ballet, for example, a designer may use white costumes to signify purity and red to express passion. Decorations, such as a tiara, can indicate royalty. Theatrical dress often exaggerates the meanings of everyday dress. For example, a clown may wear an ill-fitting, brightly colored suit to express humor.

Why clothing varies around the world

Many things influence people’s clothing choices. Some of the most important influences are geography, economics, and political beliefs, as well as cultural beliefs and values.

Geography and economics.

In ancient times, geography determined what materials people could use for clothing. People created clothing from what they could find where they lived. Growers cultivated silk in China and linen in Egypt. In Mesopotamia (now mostly Iraq), the people herded sheep and used wool for clothing. Trade altered this pattern. For example, the Silk Road—a group of trade routes that connected China with Europe—brought silk, and eventually the knowledge of how to produce it, to western Europe.

Many people still wear clothes made from the textiles traditionally produced in their region. Chinese fashion, for example, uses many silks.

Today, global trade has made all kinds of clothing materials available throughout the world. The international trade network brings ready-made clothing to stores and marketplaces in every nation. Industrial clothing factories operate in nearly all nations of the world. Most nations also produce handmade clothing and textile crafts.

The wealth available to produce and purchase clothing varies greatly among countries. Many clothing factories in less developed countries take advantage of low wages paid to workers who manufacture clothes. Corporations based in wealthy countries own many such factories.

People also differ in their ability to afford clothing. In some African nations, special markets called salaula << sah lah OO lah >> sell inexpensive second-hand clothing. Few people in these countries can afford the garments produced by local tailors and dressmakers, or imported ready-made clothes. In contrast, wealthy people throughout the world purchase new designer fashions each year.

Political influences.

Political systems may demand certain kinds of clothing. For example, in England during the Middle Ages, about the A.D. 400’s through the 1400’s, sumptuary laws specified what members of the aristocracy and royalty could wear. The laws set out the exact colors, fabrics, and furs permitted. Chinese emperors of the 1300’s through the 1600’s proclaimed rules for the colors and designs of the robes worn by nobles and officials. The rules dictated which nobles could have dragons on their robes, the number of claws on the dragons, and their placement. For example, during certain periods in China, only members of the emperor’s family could wear yellow robes with nine five-clawed dragons.

People outside of government also use clothing for political reasons. The Indian nationalist leader Mohandas K. Gandhi urged his followers to wear homespun cotton to send a demand for economic and political independence to the British colonial authorities. A teenager may dress in punk styles, which include torn clothing, leather jackets, spikes, and heavy boots. Punk fashion sends a message of rebellion.

Cultural beliefs and values.

Anthropologists, the scientists who study groups of people to determine their similarities and differences, believe clothing styles reflect people’s beliefs and values. Such beliefs and values include religious beliefs. For example, Islam prohibits artists from making images of living things. Muslims avoid wearing such images on their clothes. In contrast, the Chinese believed such images embodied the power and characteristics of the animals. Consequently, they often embroidered these motifs on their robes.

Cultural values also determine clothing styles. For decades, only outdoor laborers, such as farmers and cowboys, wore jeans. Today, people of all classes and age groups wear them. The popularity of jeans reflects the importance of comfortable, casual clothing in modern society.

Clothing strongly reflects cultural values about men and women. Until the 1940’s, European and American women rarely wore pants. People viewed trousers as masculine garments. During World War II (1939-1945), women working in factories and doing other war service wore trousers when the work demanded it. Today, women wear pants on almost any occasion. This change in styles reflects women’s changing role in society.

Japanese society imposes strong expectations of modesty and virtue on women. These qualities appear in the delicate patterns of a woman’s kimono, a traditional garment that consists of a long robe tied with a sash. Geishas, Japanese women trained to entertain men, wear elaborate clothing that prevents them from doing hard work. In contrast, some societies value hard labor. The short, full skirts and sturdy shoes of the Sami women of Finland reflect these values. In Finland, women must do their share of the work.

How clothing is made

Throughout the history of clothes, there have been two primary methods for making them—draping lengths of material around the body, or cutting materials into shapes and sewing them together to fit the body. The oldest clothing ever found consisted of animal skins wrapped around the body. The invention of bone needles more than 25,000 years ago enabled people to sew skins into more fitted clothing.

Handmade clothing.

In prehistoric times, people discovered that plant and animal fibers could be twisted into string and then braided, knotted, or interlaced. This discovery led to the first netted garments—clothing made up of a series of knots tied in thread.

More than 8,000 years ago, people invented the loom—a frame for making woven cloth. Weaving also changed how clothing could be made. Evidence of highly developed woven cloth goes back at least 7,000 years.

As early people began to settle in villages, they learned to grow plants for fibers and to herd animals for wool. As a result, supplies for making woven cloth became more plentiful. These changes took place over thousands of years. Cloth became common late in the New Stone Age, in about 4000 B.C.

In the preindustrial past, before about the A.D. 1700’s, many people found it difficult to get clothing. Making clothing required far more work than did producing food. Caring for animals and harvesting and processing fibers to weave into cloth took many hours of hard labor. This effort made cloth precious. Many early societies draped woven cloth into garments without cutting or sewing. One possible reason may have been that people did not want to waste any of the fabric that had taken them so much effort to make.

Among the earliest cut-and-sewn garments were tunics, T-shaped garments made from widths of fabric sewn together. Some tunics had additional fabric attached for the sleeves. The only cuts made might shape the neckline. Variations on the tunic can be found in the traditional dress of many countries. The Japanese kimono, for example, is a kind of tunic. Another example is a blouse worn in Mexico, the huipil << wee peel >>. The Maya of Central America and south Mexico created it.

Factory-made clothing.

The ways in which people made clothing began to change with the Industrial Revolution, a period of rapid industrialization that started in the 1700’s. Machines began to replace the hand labor that for thousands of years had been necessary for clothing production. For example, the spinning wheel, which developed by at least the A.D. 1000’s, made it possible for a worker to efficiently spin several threads into one strand of yarn. James Hargreaves, an English weaver, invented the spinning jenny in about 1764. It had eight spindles and so could spin many threads into eight strands of yarn at the same time. A later improved version could produce 16 strands of yarn at the same time. In 1779, the English weaver Samuel Crompton developed the spinning mule. Later versions of this machine produced high-quality yarn on hundreds of spindles at a time. In 1801, Joseph Marie Jacquard, a French weaver, introduced a loom for patterned weaving. The loom used cards with punched holes to determine the pattern.

Replacing hand work with work done by machine—a process called mechanization—continued throughout the 1800’s and 1900’s. Technological development greatly changed clothing production. By the early 2000’s, a technician could push a button on a computer to begin production of a finished garment many miles or kilometers away.

Clothing materials.

Early people used natural furs and leathers to make garments. Natural fibers that have been used in clothing for thousands of years include cotton, linen, silk, and wool.

The French chemist Hilaire Chardonnet invented the first practical manufactured fiber, later called rayon, in 1884. Synthetic fibers are made by chemical processes. Rayon comes from cellulose (plant fibers). Since the early 1900’s, researchers have produced new synthetic fibers with amazing properties. Scientists have developed new fabrics for people to wear while exploring space and while driving race cars, as well as fabrics for sports equipment and body armor. As a result, new fibers have become available for clothing. Textile manufacturers often blend synthetic fibers with natural fibers to take advantage of the properties of both.

The globalization of fashion

Economic globalization can be defined as an increasingly international approach to the production, distribution, and marketing of goods and services. By the 2000’s, fashion had become global. Many people throughout the world dressed in similar styles. This similarity resulted in part from the development of a global fashion industry that produced a huge volume of ready-to-wear clothing. In addition, new electronic technologies rapidly spread fashion information to a worldwide audience.

In isolated societies, fashions in clothing change more slowly and remain more regional. Regional clothing styles also persist in societies where people have limited access to ready-made clothing, or where they have little income to spend on their choice of apparel.

Regional traditional costumes.

In the 1800’s, an idea known as nationalism developed in Europe. Nationalism consists of a people’s sense of belonging and loyalty to a nation. Different areas of Europe had developed special types of dress. With the rise of nationalism, Europeans identified certain clothing styles as part of what marked them as a nation. The style of dress in various nations became known as regional traditional costume. Some people refer to these garments as folk costumes. Today, people dress in such costumes mainly for festive occasions or special events.

Outside of Europe, traditional dress had a longer history. Changes came about more slowly. The traditional clothing had roots in deeply held beliefs, customs, and social systems.

International fashion

began in European courts in the Renaissance, a cultural movement that began in Italy during the early 1300’s. Fashion became more similar from country to country because of the intermarriage of rulers and because of shifting centers of political and economic power.

International fashion dominates clothing production today. Many styles originate in such urban fashion centers as London, Milan, Paris, and New York City. By the early 2000’s, designers from many countries throughout the world had joined the international fashion system.

International fashion and traditional costume span the globe, and sometimes combine. In Japan, a bride might wear a traditional kimono for part of the ceremony and then change into a white, Western-style wedding gown. In the Middle East, women may dress in high-fashion clothing from Paris. When out in public, however, they may cover the fashionable clothing with a traditional abaya << uh BY uh >>—a long black robe. Runway fashions in Africa may combine traditional textiles and patterns in internationally fashionable styles.

Clothing of the ancient world

For around 100,000 years, humans have worn clothing of some kind. They made the earliest clothing of furs. Scientists believe people fashioned garments from both skins and fur by around 5,000 to 6,000 years ago. They fitted and sewed some of that clothing.

Mesopotamia.

The people of Mesopotamia used wool as the primary fiber for garments. Sculpture from the 2000’s B.C. from ancient Mesopotamia depicts men wearing wrapped skirts. Later statues show tunics with decorated edges under large, fringed shawls for both men and women.

Egypt.

Most of what scholars know about ancient Egyptian clothing comes from archaeological excavation. Tomb paintings from the New Kingdom (about 1539 B.C. to 1075 B.C.) show men wearing tunics with a cloth wrapped around the waist to make a kind of kilt. The paintings depict Egyptian women wearing wrapped garments or narrow, sleeveless tunics. Archaeologists have excavated linen garments from Egyptian tombs. The climate in Egypt is hot, and so people dressed in linen, which is cooler than wool.

Both men and women wore wigs in ancient Egypt. They shaved off their hair to stay cool but put on wigs for special occasions. The wigs may have been made of human hair, palm-leaf fibers, or wool. Jewelry had importance throughout the ancient world. Archaeologists have excavated striking gold headdresses from the tomb of the pharaoh Tutankhamun in Egypt.

Crete.

The people of the Minoan culture, who lived on the Mediterranean island of Crete from about 3000 B.C. to about 1100 B.C., dressed in fitted garments. Statues of priestesses show a tightly fitted bodice (upper part of a dress), which exposed the breasts, and ruffled skirts. Minoan men shown leaping over bulls in wallpaintings wear a tightly fitted garment around their hips. On their feet are short, soft boots with pointed toes. In other paintings, men and women dress in long wrapped and girded (belted) garments made from a length of fabric with decorated edges. The Minoans arranged their hair in long ringlets.

Greece.

On ancient Greek pottery, both men and women wear variations of draped, uncut lengths of cloth called chitons << KY tuhnz >>. A type of pin called a fibula << FIHB yuh luh >> held the chiton together at the shoulder. The garments are soft and flowing. By belting the chiton in different ways, the Greeks varied its look. One kind of chiton was a sleeveless outer robe called a peplos << PEHP luhs >>. Artists often depicted the goddess Athena wearing a peplos, and the Greeks gave a special peplos to Athena as an offering each year.

The Greeks sometimes wore a large, rectangular, wrapped and draped garment called a himation << hih MAT ee ahn >> over the chiton. Instead of a himation, Greek soldiers wore a short cloak called a chlamys << KLAY mihs >> that left the fighting arm bare.

Wool and linen ranked as the most common fibers in ancient Greece. Later in ancient times, silk became available. Greek traders likely imported silk from China through Persia (now Iran).

Rome.

The ancient Romans borrowed clothing styles from the Greeks and the Etruscans, a northern Italian people who ruled Rome from 616 to 509 B.C. The Romans called their basic garment a tunica << TOO nuh kuh >>, the origin of the English word tunic. Slaves and low-ranking men dressed in simple tunics. Noble Roman men and women wore two garments, an under tunic and an outer tunic. They covered the under tunic in public and slept in it at night. Roman women dressed in long outer tunics called stola << STOH luh >> with a cloak known as a palla << PAL uh >> over their shoulders.

Men who had the status of Roman citizens wore an outer tunic with a toga over it. The toga hung over the left shoulder and wrapped around under the right arm. Unlike earlier wrapped garments, the toga had a semicircular shape. The toga may have derived from a similar garment called a tebenna << tuh BAYN uh >> worn by the neighboring Etruscans. Only people who belonged to the privileged class of citizens of Rome could wear the toga. Slaves and noncitizens were forbidden to wear it.

Wool and linen were the most common fibers in Roman garments. The Romans imported woolens from Britain and Gaul (mainly present-day France), linen from Egypt, cotton from India, and silk from China and Persia.

The Romans developed some of the first factories for producing clothing. They also traded ready-made garments throughout their empire. Because the Roman Empire covered a large geographic area, many other cultures adopted Roman styles of dress.

Clothing under Islam

The rise of Islam in the Middle East began in the 600’s A.D. By 1500, the Ottoman Empire, centered on what is today Turkey, extended Islamic influence from Asia Minor and the Balkans to northern Africa, present-day Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Syria. In 1683, the empire’s expansion ended with a failed attack on Vienna, Austria. Trade flourished throughout the empire. Elements of Ottoman style and decoration appeared in traditional costumes wherever the Ottomans ruled.

A T-shaped tunic called a caftan served as the most common garment for Muslim men and women, and continues to do so. The caftan, also spelled kaftan, often opened in the front. People layered it over additional tunics and trousers. Full trousers covered the body from the waist down. Buttons, which may have come to the Middle East through trade with China, decorated the garments.

Head coverings play an important role in Islamic dress. Many men wear a simple square of fabric folded into a triangle and draped over a close-fitting cap. More elaborate styles of turbans have also developed.

In some Islamic countries, women veil themselves in public and in the presence of men not in their immediate family. Many Muslim women wear an abaya. This long black robe covers the woman’s head and drapes over her other clothing. It covers a woman from head to toe. Other Muslim women conceal their hair and sometimes the lower part of their face with a large scarf known as hijab << hih JAHB >>. A woman wraps such a scarf around her head and then drapes it over her shoulders.

Clothing of Africa

Civilization developed in various regions of Africa over many centuries. City-states of the east African coast arose from settlements existing after A.D. 100. The great empires of west Africa emerged around A.D. 700. Each area of the continent had different clothing needs. Many of these cultures traded extensively. Clothing styles showed influence from trading partners in Egypt, China, India, the Middle East, and, later, western Europe.

Different areas of Africa produced a number of indigenous (native) fabrics. Weavers in Ghana produced narrow bands called kente << KEHN tay >> cloth that were sewn together to make full robes. In central Africa, the Kuba made clothing from raffia (fiber obtained from palm trees) and bark cloth. African craftworkers decorated some textiles with block printing or resist dying. In resist dying, wax or a similar substance is painted on a fabric to prevent dye from coloring some areas.

In non-Muslim Africa, clothing consisted primarily of wrapped skirts and tunics. People in some cultures wore little or no clothing. Instead, they decorated their bodies with paint, scarification (cutting the skin to make patterned scars), ornaments, and headdresses. Each group’s body art and ornaments identified its members by gender and status. The Maasai people of Kenya and the Zulu from southern Africa wore elaborate beadwork, for example. Body painting decorated Suma men in Ethiopia.

Beginning in the 1500’s, European colonization influenced African clothing choices. It also gave Africans access to commercially produced textiles and to clothing styles much different from traditional ones.

By the 1900’s, ready-to-wear clothing made international fashion available in Africa. In most urban areas of Africa, people wear international styles rather than traditional garments. However, in the late 1900’s, a strong current of pride in being African began to influence clothing choices. Many designers incorporated elements of African traditional design into their creations. For example, they might ornament an evening dress with traditional beadwork, or fashion kente cloth into a modern garment.

Clothing of Asia

The use of horses in Asia brought about the development of trousers to protect the rider’s legs. A mummy of a non-Chinese man discovered near Cherchen, western China, wore well-preserved clothing dating to about 1000 B.C. This man was dressed in maroon trousers and a matching shirtlike tunic. Overcast stitches in red wool decorated the seams.

India.

At the same time as Babylon in Mesopotamia and the Old Kingdom of Egypt, civilization flourished in the river valleys of what are today India and Pakistan. This is known as the Indus Valley civilization. Scholars believe that people in India began to weave cotton into cloth some time between 3000 and 2000 B.C.

As far back as the Indus Valley civilization, evidence in the form of stone sculptures appears to show men wearing wrapped garments. Hindu men wrapped a large cloth called a dhoti << DOH tee >> around the waist and between the legs. Men also wore a scarf or shawl on their shoulders. The dhoti and shawl served as the basic garments for 2,000 years. Women dressed in a variety of wrapped skirts as well as a dhoti, and a large scarf called a dupatta << doo PAH tah >>.

With the Islamic invasions beginning around the A.D. 700’s came different costumes. Although women in India did not veil their faces, they did begin to wear short blouses called choli << CHOH lee >> to cover their breasts. Men wore a long-sleeved, knee-length coat with a full skirt. Turban styles in India varied over the centuries, but such headwear consistently identified the wearer’s region, caste, and religion.

Despite exposure to European dress beginning in the 1600’s, few Indian men and women adopted international fashion. Around the time of Indian independence in 1947, Indian men began to dress in a tailored, knee-length jacket that buttoned down the front over narrow trousers. Both men and women wear a casual style consisting of a long khurta (shirt) and loose trousers.

The garment most associated with Indian women, the sari, had been known for hundreds of years. Modern sari makers often weave them with special borders and decorative panels.

China.

Along with the other civilizations of antiquity, China developed distinctive garments based on T-shaped and wrapped constructions. Chinese farmers grew the hemp plant for its strong fiber and commonly used it for clothing. Silk production, or sericulture, however, remains as China’s most lasting contribution to world fashion.

Statues of men from the Zhou << joh >> period (about 1045 B.C. to 256 B.C.) wear knee-length, T-shaped robes that close at the front. Men layered the robes over long skirts and cinched them with a belt. By the end of the Zhou period, men began to dress in a short jacket and trousers, probably adopted from the horse-riding peoples of Central Asia. The terra-cotta statues of cavalry soldiers buried near Xi’an, China, in the 200’s B.C. wear such trousers. The design would have been especially useful for archers on horseback.

Variations on the combination of short jacket and loose trousers remained a constant of Chinese dress for both men and women for the next 2,000 years. During the Han << hahn >> dynasty, which began in 206 B.C., women began to wear a knee-length jacket and an ankle-length skirt. The Han ethnic group in China wore this style until the end of the Qing << ching >> dynasty in A.D. 1911.

Chinese rulers wrote regulations that established a hierarchy of dress—that is, organized ranks of clothing styles based on the wearer’s social class. Only specific classes of people could wear certain colors, symbols, and styles. During the reign of the first Tang << tahng >> emperor in the A.D. 600’s, for example, laws regulated the amount of fabric that could be used in sleeves based on a wearer’s status.

With the establishment of the Republic of China in 1912, Chinese men began to dress in business suits like those worn in Europe and the Americas. Women wore a slim sheath dress called the qi pao << chee pow >>. Under Communism, from 1949 until the mid-1970’s, Chinese men and women dressed in the “liberation costume,” a short tunic and loose-fitting trousers.

With China’s increasing wealth, Chinese men and women have adopted international fashion. In the early 2000’s, China manufactured much of the clothing sold worldwide.

Japan

developed distinctive modes of dress in the A.D. 600’s and 700’s. During the Heian << hay ahn >> period (794-1185), Japanese men began to wear a full, divided skirt called a hakama << hah kah mah >> with a belted, wrapped, T-shaped robe—the kimono. Women began to dress in multiple layers of kimono called the juni-hitoe, or “twelve-layers” costume. In the Edo << ee doh >> era (1603-1867), a number of different kimono shapes developed. Both men and women wore a short-sleeved style called kosode << koh soh deh >>. Men might add a haori << how ree >>, a three-quarter-length kimono, over their kosode. The furisode << foo ree soh day >>, or “swinging sleeve” kimono, had long sleeve extensions. Only unmarried girls wore it. For a wedding, the bride might wear a brocaded (woven with raised designs) and embroidered kimono with a train and long sleeve extensions. This garment was called an uchikake << ooh kee kah kee >>. Elaborate wide brocaded sashes called obi became important accessories for women in the Edo period. Women tied these sashes in elaborate knots and bows.

By the early 2000’s, Japan participated fully in the international fashion system. Some young Japanese adopted Western popular styles, such as punk and hip-hop. Popular hip-hop fashions include baggy clothing and heavy gold jewelry. Some teenage Japanese girls wear a look called kawaii << kuh wah ee >>, from the Japanese word for cute. The kawaii style combines children’s fashions with styles based on Japanese anime cartoons and manga comic books.

Korea.

The Korean traditional dress, a full-skirted style called hanbok, may have been influenced by Chinese costumes of the Tang dynasty, a family that ruled from A.D. 618 to A.D. 907. The hanbok gradually evolved over centuries to a specifically Korean costume. The Koreans wove fabrics from hemp, a plant fiber called ramie, and silk. They began to use cotton in the A.D. 1300’s. Korean tailors and dressmakers traditionally basted garments together—that is, sewed them with long, loose stitches—so they could be taken apart for laundering.

Both men and women in Korea wore pants called baji << bah jee >> (or paji) and jackets called jogori << juh goh ree >> (or jeogori). Men also dressed in long coats, some with full skirts. Women wore long, gathered, wrapped skirts called chima << chee mah >> (or jima) over the pants. They also veiled their faces when out in public.

Women’s jackets wrapped left over right and tied at the side front. Over time, jackets became shorter and skirts higher and longer. Colors, decorative elements, and style of headdress all indicated the wearer’s social and military rank. A woman dressed in keeping with her husband’s rank. Men wore black horsehair hats, many with tall crowns and wide brims.

By the late 1900’s and early 2000’s, Koreans dressed in hanbok mainly for family celebrations and formal occasions. Styles inspired by the hanbok may even appear on a the runway at fashion shows, sharing attention with the latest international fashions.

Clothing of Native Americans

People living in Mesoamerica—the area that today covers Mexico and Central America—did not need clothing for warmth. They probably wore little more than loincloths, wrapped skirts, ornaments, and body paint. The first textiles in Mesoamerica were made by twining (twisting threads) and netting (knotting yarns).

By around 1500 B.C., loom weaving had appeared in Mesoamerica. From about A.D. 350 to 650, statues of women from Teotihuacán, near Mexico City, show a poncholike top and a wrapped skirt. The tunic called the huipil developed between 800 and 1200. It remains a basic upper garment for women in many parts of Mesoamerica.

Maya and Aztec.

Statues depict men of the Mayan culture wearing loincloths; wrapped, rectangular cloaks; and sleeveless coats open at the center front. The garments had bright colors and lavish ornaments. The quality of the cloth and the kinds of decoration signified the wearer’s social status. The Maya also decorated their skin with tattoos and scarification.

Aztec warriors wore padded and fitted upper-body garments. They sometimes dressed in a cotton bodysuit with sleeves and legs covered with feathers.

Inca.

Ancient cultures of the Andes Mountains, including the Inca, made remarkable fabrics. Mummy bundles from 450 B.C. to 175 B.C., found in Peru, were wrapped in colorful textiles. The wrappings consisted of complex tapestry (fabric woven from threads of different colors to form a design). A cloak, loincloth, and variations on a tunic served as the basic costume for men of the Andes. Women wore a T-shaped tunic or a wrapped dress and shawl.

Indians of North America.

The Paleo-Indian cultures—people who lived in the Americas from about 13,500 to 8,000 years ago—wore wrapped garments made of skins. Their descendants, the Eastern woodlands tribes, continued to wear skins and T-shaped tunics with moccasins. The tribes of the Great Plains also wore these basic garments. The Indians decorated their clothing with fringe, quillwork (patterns made of porcupine quills), feathers, bone, beads, and shells. Men wore feathered headdresses in ceremonies.

Indians of the Southwest developed cloth made of hemp and cotton woven on looms. Women in the Southwest dressed in two widths of fabric fastened at the shoulders, left open at the sides, and belted. Men wore woven loincloths.

People in the Pacific Northwest wore little clothing except in winter, when they dressed in skin capes, leggings, and moccasins. People of the Arctic regions skillfully cut and sewed skins and furs. They dressed in a T-shaped tunic with long sleeves, knee-length or ankle-length trousers, high boots, and a hooded coat. They also wore gloves and mittens and an early form of snow goggles carved of wood.

Clothing of Europe

The Middle Ages

began with the fall of the West Roman Empire in the late A.D. 400’s and lasted until about the 1400’s. At the start of the Middle Ages, men and women in western Europe continued to wear clothing in the style of the Romans, with over tunics and under tunics, cloaks, and shawls.

The fall of Rome at the end of the 400’s left the Eastern Roman Empire, called the Byzantine Empire, as the center of political and economic power. The Byzantine emperor and empress wore large cloaks called paludamentum << puh loo duh MEHN tum >> On the cloak, a large rectangular ornament called a tablion << TAHB lih ohn >> showed the wearer’s status.

The people of the Byzantine Empire had learned the secret of silk production by the 500’s. Within the empire, the emperor controlled the production of silk and trade in the costly fabric. The Byzantine influence inspired the increased use of silks and jewels on the garments of the ruling classes throughout western Europe.

In the late Middle Ages, between 1000 and 1500, royal courts became more luxurious. What historians consider to be international fashionable dress began in these courts. The Crusades—Christian military expeditions to the Holy Land from the late 1000’s to the 1500’s—brought back many new textiles and ideas about dress from the Middle East. In addition, Marco Polo and other travelers returned from China in the 1200’s with vivid descriptions of the clothing and luxuries of Asia. Trade along the ancient Silk Road brought increasing varieties of costly silk fabrics for the kings and members of their court.

The amount and kinds of fabrics and ornaments used to make a garment reflected the wearer’s social class. The lower classes continued to wear locally produced wool and linen. The basic costume for all, however, consisted of an under tunic called a cote and an over tunic called a surcote (also spelled surcoat). Even soldiers dressed in a variation on this costume. They wore shirts made of interlocking metal rings, called mail, over a padded shirt called a gambeson. Over the mail went a colorful surcote decorated with heraldic designs, symbols used to represent noble families.

People could purchase some unfitted garments and accessories ready-made. But the wealthy had the majority of their clothing made especially for them. Lower-class people made their own clothing at home. During the 1100’s, the manufacture of clothing grew more specialized. Such skilled workers as weavers, tailors, and cobblers (shoemakers) appeared.

The Renaissance

began in Italy in the 1300’s. Urban centers developed in western Europe, and trade flourished. The court of Burgundy, now in France, ranked as one of the most luxurious. Men in this court wore a shirt under a short doublet, a type of jacket. They laced the doublet to their leggings. As an outer layer, they donned a full and flowing robe called a houppelande << HOOP lahnd >>. The houppelande consisted of richly colored velvet, satin, or wool, often trimmed or lined with fur. With this outfit, men wore shoes with long pointed toes called poulaines << poo LAYNZ >>.

Women in the court sometimes wore houppelandes over a long, closely fitted gown called a cote. They might wear a surcote over the cote. A woman’s surcote had no sleeves or sides at the bodice. The skirt was so long that a woman had to lift it to walk. Because members of the nobility spent their days at court attending the ruler, they had little need for practical garments.

Women’s headdresses were an important accessory. Only unmarried girls, brides, and queens could appear with uncovered hair. In Burgundy, a tall cone-shaped hat now known as a hennin became stylish.

As the merchant class grew wealthier, they began to acquire more clothing and fashion changed more rapidly. The middle class usually modeled their fashions on those of the court, but their clothes were less luxurious and the styles were more conservative. Peasants who worked the land continued to wear layers of belted tunics with stockings, cloaks, hats, and boots or clogs for warmth and protection.

Italy produced some of the most beautiful textiles ever known, woven of richly colored silk with gold and silver threads. Clothing displayed the family’s wealth and status, especially when a daughter became a bride. At the end of the 1400’s, clothing for the wealthy became more closely fitted to the body.

The 1500’s saw dramatic changes in the construction of European fashionable dress, due in part to the power and influence of Spain. The age of exploration had brought riches to Spain from many parts of the world. Trade spread new dyes, fabrics, and ideas about dress.

For women’s gowns, the bodice became fitted and stiffened with boned stays, an early version of a corset. Hoops and padded rolls at the waist held out skirts. In another change, bodices were stitched to skirts with a seam at the waist. One long-lasting change in women’s dress appeared late in the 1500’s. A split up the center front of the overdress revealed a decorative underskirt. This style endured with some variation into the 1800’s.

Men wore doublets with peasecod fronts—padded fronts that resembled the chest of a bird. The upper hose worn with the doublet, called trunk hose, became round, padded shapes called “pumpkin” hose.

Stiff and padded shapes continued for the first two decades of the 1600’s for wealthy and powerful men. Members of the merchant class dressed elegantly but more conservatively. Laborers wore simple garments.

Men and women wore a linen chemise << shuh MEEZ >>, a shirtlike tunic, next to their skin. People could easily launder linen undergarments. But the fabric and decorations used for many outer garments made them difficult, or impossible, to wash.

Embroidery decorated the neck and cuffs of the chemise. In the late 1500’s, people began to wear a stiff, frilly or ruffled collar known as a ruff. Ruffs consisted of fine lace or linen gathered and pleated to a neckband. Starch made the fabric stand out from the neck.

The 1600’s.

France dominated fashion in the 1600’s. Both men and women began to wear shoes with heels. Men’s breeches changed, first from pumpkin hose to breeches that ended below the knee and tucked into boots. Full, wide-legged “petticoat” breeches followed. Then came narrow knee breeches. Ribbons decorated men’s coats, breeches, and shoes.

One of the most important changes in men’s fashions occurred when King Charles II of England, who had spent time in France, decided to wear a three-piece outfit. The three pieces were a knee-length coat, a waistcoat (vest), and knee-length trousers. This costume developed over the next century into what today is known as a “three-piece suit.” Soldiers in the 1600’s wore leather coats, broad-brimmed hats with plumes, and tall boots.

Women’s costumes included gowns with a raised waist. An opening in the front of the skirt showed the underskirt. Women might also wear a hip-length jacket. The Puritans in England and Puritan colonists who came to America wore more conservative colors and avoided lavish ornamentation.

In the late 1600’s, women began to dress in gowns with the bodice and skirt cut from a single piece of cloth. This garment, called a mantua, opened in front to reveal a decorative underskirt or petticoat. The overskirt could be pulled back and formed into a train. The mantua became the dominant style for women’s clothing into the 1700’s.

Clothing of Europe and the Americas

The 1700’s

brought technological advances that revolutionized textile production. Machines to spin and weave could produce far more thread and cloth than could be made by hand. Machine-woven cloth became less expensive. Only luxury silk, lace, and embroidery continued to be handmade.

For the upper classes, international fashion in the 1700’s changed rapidly. Styles worn at the French court influenced these changes. For men, the styles revolved around the fluctuating length and shape of the coat and waistcoat. For women, the mantua and underskirt had either a flowing back or a tightly fitted back. Both styles had a triangular covering for the stomach and chest called a stomacher that filled in the front of the bodice.

An oval hoop called a pannier << pan yai >> held out skirts at the sides. The hoops grew in width until, by mid-1700’s, some measured more than 60 inches (150 centimeters) from side to side.

Later, the width of skirts decreased. By the 1780’s, the fullness of the skirt moved to the back, forming a gathering of material called a bustle. English fashions became influential in the mid-1700’s. English tailoring remained important in men’s fashions long after.

Prior to the American Revolution (1775-1783), wealthy American colonists wore fashionable clothing and imported luxury silks from England. The less wealthy made stylish garments from simpler fabrics, including imported woolens and cottons, and homespun wool and linen. Fashion information crossed the Atlantic Ocean with every merchant ship that sailed, so the colonists kept up to date on the latest styles. To protest new British taxes in the 1760’s, the colonists organized a boycott of English goods, including textiles. Instead, they relied on fabrics manufactured in the colonies, usually at home.

During the French Revolution (1789-1799), fashion became political. The styles associated with the French monarchy, including exaggerated hairstyles and hats, went out of fashion. Full-length trousers, previously worn only by workingmen, replaced the knee breeches of the former monarchy. Fashions inspired by ancient Greece and Rome became popular. Both men and women cut their hair short. The red, blue, and white colors of the revolution appeared in the cockade, a knot of ribbon or a rosette worn on hats and shoes.

The 1800’s.

At the beginning of the 1800’s, Napoleon came to power in France and established the First Empire. Women’s fashions continued to be modeled on ancient Greece. Gowns had a high waistline starting just below the bust. Such dresses are still known as Empire style. From the narrow column of Empire fashion, skirts began to widen. By mid-century, a bell-shaped hoop held out expanding skirts. Sleeves also grew wider. The first leg-of-mutton sleeves appeared in about 1828. Leg-of-mutton sleeves are wide at the upper arm but narrow and close-fitting at the wrist.

The fashionable Englishman George Bryan (Beau) Brummell influenced men’s fashion early in the 1800’s. He wore well-tailored coats and vests in dark colors with light trousers and white linen shirts and cravats. Clothing for men became increasingly conservative in color and cut through the century.

By the mid-1800’s, the American inventors Elias Howe and Isaac Singer had developed improved sewing machines. The machines made the manufacture of clothing much easier. The outbreak of the American Civil War (1861-1865) created a need for large numbers of uniforms and stimulated the ready-made clothing industry. The advent of new machines and production capabilities made possible the mass production of apparel. Those who could afford handmade garments continued to buy from tailors and dressmakers, but more and more machine work became part of the process.

After the wide skirts of the mid-1800’s, skirts narrowed again during the 1870’s and 1880’s. Any fullness moved to the back, creating new versions of the bustle. Bustles included hoops, springs, and pads that extended the rear of the dress and supported the drapery of the skirt. The second appearance of large leg-of-mutton sleeves characterized women’s fashions in the 1890’s, as did trumpet-shaped skirts.

The 1900’s and 2000’s.

The most notable change for women’s fashions began in the 1920’s—shorter skirts that made physical activity easier. Trousers became an acceptable garment for women in the 1930’s.

The ready-to-wear clothing industry grew to provide stylish garments for the mass market. World War I (1914-1918) and World War II (1939-1945) influenced women’s fashions. During both conflicts, women worked outside the home in factory environments. This work demanded more practical clothing, to allow women to safely operate machinery. Long, full skirts tightly belted at the waist returned during the 1950’s.

Men’s suit jackets were either single-breasted (fastened with a single row of buttons) or double-breasted (fastened with two rows of buttons) during the first half of the century. Single-breasted suits with narrow lapels and shoulders, called Ivy League suits, appeared in the 1950’s. Sportswear separates for men and women became increasingly popular. The development of synthetic fibers made more clothing “wash and wear.”

In the 1960’s and 1970’s, more informal fashions became acceptable as office attire. Men began to dress in bright colors. They wore colored shirts, rather than only white ones, with business suits. Women began to enter the workforce in significant numbers. As a result, they needed clothing appropriate for office environments.

The youth culture developed an “anything goes” attitude toward fashion, represented by T-shirts and blue jeans. Different kinds of popular music became influential in youth fashion. The popular rock group the Beatles inspired their fans to grow their hair long and wear clothing reflecting earlier, more ornamental styles. Later, such movements as punk, hip-hop, and goth also influenced youth fashion.

In the 1990’s, dress codes became more relaxed, especially in technology industries. Young computer engineers wanted to be comfortable and avoided business suits. The ”business casual” look spread from tech industries to other companies in the first decade of the 2000’s.

The emergence of Japanese designers at the end of the 1900’s stimulated international fashion. These designers, including Issey Miyake << ihs say mih yah kay >>, showed their collections in Paris as well as Tokyo.

The clothing industry

Clothing ranks as one of the largest industries in the world. The clothing industry includes the manufacture of everything that men, women, and children wear. It also includes the production of all the materials and decorative elements that go into any garment. Clothing is also one of the most globally interdependent industries. The pieces of a garment may be manufactured in several different countries, assembled in another country, and sold in still other countries.

Since the start of the Industrial Revolution, owners of clothing factories have sought ever-cheaper methods of production. In the 1900’s, this meant mass production and moving operations to countries with lower labor costs.

A growing interest in sustainable fashion—that is, clothing compatible with the long-term well-being of the environment—challenged the clothing industry at the start of the 2000’s. Great quantities of mass-produced garments exact a toll on the environment, especially when many remain unsold and ultimately must be discarded. Some designers and producers seek to use advancing technologies to make fashion production more sustainable.

Careers.

Manufacturing and merchandising offer the majority of career opportunities in the clothing industry. Colleges and universities teach courses in fashion design, merchandising, and many other topics that relate to clothing.

Many types of workers help bring clothing to the market. A merchandise manager for a clothing manufacturer must try to anticipate what people will want. Merchandisers can determine demand much more quickly than in the past. In addition, improving production technologies enable manufacturers to change product specifications to keep up with rapidly changing demand. These developments have permitted the evolution of fast fashion in the 2000’s. In a fast-fashion environment, a store displays merchandise as soon as the store receives it. If a style sells quickly, the store will order more and the manufacturer will rapidly produce it. If the clothing does not sell within a few days, different merchandise replaces it.

In clothing, product development—based on trend forecasting and market analysis—determines the designs produced. Trend forecasters play an important role in helping to determine future demand. These forecasters try to predict the colors, fabrics, and styles consumers will want in the future.

Manufacturers hire teams of designers to create products based on trend analyses. They must make their products different from those of their competitors by understanding what the customer expects from their brand. Designers try to meet customer expectations with fresh new styles.

Design careers also include technical designers who communicate and verify assembly methods, production pattern makers who insure the integrity of the designs being produced, and specification writers who determine the materials from which a garment will be made. Careers in textile design and development include textile technologists, color managers, print managers, and laboratory technicians who test the durability and strength of fabrics.

Preparations for production require costing engineers to analyze assembly operations and determine the cost of making a garment. Logistics specialists make sure that all the parts of a fashionable outfit arrive at the store at the same time, no matter where they are produced.

Marketing categories of fashion.

Clothing is divided into many smaller markets dedicated to certain types of customers. The most expensive category for clothing is haute couture << oht koo toor >> Fashion houses make haute couture to order for the person who will wear it. A customer purchases haute couture at a designer’s store and has it fitted at the designer’s workshop. Haute couture rarely makes a profit, but it creates an atmosphere of glamour from which an entire business can profit. For example, the Christian Dior brand has an haute couture division, a ready-to-wear division, and licenses for perfumes and other products.

Manufacturers make ready-to-wear clothing to fit standard sizes and sell it in stores. Within the ready-to-wear category are a number of marketing categories. They include, from the most expensive to the cheapest, designer, bridge, moderate, and discount or secondary clothing. Designer clothing bears the label of a well-known fashion designer. Many designers also create a line of less expensive bridge clothing with special labels. Moderate clothing has a well-known brand name, but not a designer label. Clothing for the discount or secondary market is made especially for chains of discount stores and often bears a store label.

The categories of garment production have become increasingly blurred. A manufacturer may now choose to show examples from all the categories in the same fashion show. In the past, fashion shows primarily displayed top-of-the-line, expensive garments.