Convicts in Australia and their supervisors were the earliest European settlers on that continent. From 1787 to 1868, more than 162,000 convicts were sent from Britain (now the United Kingdom) to colonies in Australia. Other countries also sent convicts to their own developing colonies to provide cheap labor. The convicts endured banishment from their homes and the loss of their families and friends. Few returned to their native countries.

Some British convicts built successful lives in Australia, but others suffered miserable fates. For the most part, the convicts were young and healthy. Many of them could read and write. They established businesses, started families, and formed communities, thus laying the economic, social, and cultural foundations of European settlement on the Australian continent. The convicts also played an essential role in the development of the Australian wool industry. In addition, they constructed many public buildings, bridges, and roads. By the 1830’s, ex-convicts and their descendants in the colony of New South Wales were hard to distinguish from other settlers.

Background

The 1700’s were years of change and unrest in Britain. Improved farming equipment and methods made farms more productive. These advances required fewer people to produce the same amount of food. People whose ancestors had lived and worked on the land as tenants were forced to leave to find other kinds of work. Farm families by the thousands moved to the towns and cities.

Around the same time, the Industrial Revolution was changing British cities. New factories sprang up rapidly, attracting former agricultural workers who sought jobs. Rising urban populations and poverty among urban workers led to an increase in crimes, especially crimes against property. In addition, the police force at the time was not large enough to enforce the law effectively.

Punishments for people caught committing crimes were extremely harsh. They included the death penalty and transportation—that is, sending the convicted person overseas to work in a British colony. Through the years, an increasing number of offenses drew a sentence of transportation, and sentences of life imprisonment and death were often changed to transportation.

The transportation system

Beginnings.

An act of Parliament officially established transportation in 1718. However, the British government was transporting convicts more than 100 years before that. Transportation served as both a form of punishment for convicted criminals and as a way of providing cheap labor for British colonies in America. On arriving at a colony, ships’ masters sold the convicts to planters as laborers.

Following the American Revolution (1775-1783), the United States refused to accept convicts. British jails soon became overcrowded with convicts waiting to be sent overseas. As a temporary measure, the government put the convicts on hulks, ships that were no longer seaworthy. The British first used hulks on the River Thames in London and later moored them on other rivers. Convicts living on the hulks provided labor for public works projects. As the authorities saw it, this labor helped to pay for the convicts’ upkeep and to build the nation. Convicts who behaved well could earn a pardon.

The British government searched for new places where it could send the convicts. Government officials considered several locations, including parts of Africa. But Botany Bay, on Australia’s southeast coast, seemed the best choice. It was far from Britain and did not pose health threats, as did the African sites. Sir Joseph Banks, a botanist who had visited Australia in 1770, wrote a glowing account of Botany Bay. He suggested that the area was fertile enough to provide settlers with the crops they would need. In 1786, Britain chose Botany Bay as the site for a new penal (prison) colony.

The convicts

transported to Australia were mainly ordinary, working-class men and women. They had an average age of 26, were generally fit and healthy, and possessed useful skills for building a colony. About 75 percent of them could read and write. Before 1830, the convicts tended to be urban Britons; nearly half had been born in towns and cities. More than 50 percent of them were unmarried. For the most part, they were Christians—Protestants and Roman Catholics—but there were also some Jewish convicts. About 25 percent came from Ireland. Only about 15 to 20 percent of the convicts were women.

Sentences handed down for transportation ranged from seven years to life. Records show that the convicts’ offenses included almost every crime against British law. But the overwhelming majority of convicts—about 80 percent—were transported for crimes against property. These included petty larceny (the theft of items of small value), picking pockets, forgery, highway robbery, and embezzlement (stealing money placed in one’s care). Other convicts were transported for such crimes as assault, manslaughter, and offenses against military or naval discipline.

The voyage.

The first convicts who traveled to Australia sailed to Botany Bay on the First Fleet. Under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip, the fleet left England in 1787 with about 750 convicts. The convicts received humane treatment, and the death toll on the voyage was low. They arrived at Botany Bay in January 1788. The Second Fleet, which sailed later, became notorious for its cruelty and the number of deaths that occurred during its voyage from England. The British Admiralty chartered (hired) ships to carry convicts to Australia. The Admiralty then gave contracts to businessmen to transport the convicts. The contractors responsible for the Second Fleet overcrowded the ships to make room for cargo to be sold on arrival in Sydney. Although enough food had been supplied, the convicts were reduced to a starvation diet. They were rarely allowed up on deck to exercise.

When the Second Fleet anchored in Sydney Harbour in 1790, more than a fourth of the convicts had died, and nearly half were ill with fever, dysentery (an illness affecting the large intestine), and scurvy (a disease caused by lack of the vitamins in fresh fruit and vegetables). Captain Phillip protested to the government, and criminal charges were brought against some of the businessmen involved. However, they fled England before they could be brought to trial.

Improvements in the conditions governing convict ships were slow in coming. From 1802, ships’ surgeons were paid a bounty for every convict who landed in good health. Ships’ masters also received extra pay if the voyage had been properly conducted. Authorities enforced regulations that ensured convicts got enough food and fresh air. Convicts were given clothes, and overcrowding on board was banned. Exercise on deck became compulsory. These improvements lowered the death rate on convict ships.

From 1787 to 1840, approximately 80,000 men and women were sent to New South Wales. At that time, the colony included Norfolk Island and what are now the states of New South Wales, Queensland, and Victoria. From 1803 to 1853, about 67,000 men and women were transported to Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania). And from 1850 to 1860, nearly 10,000 men were sent to the colony of Western Australia.

The convict system

Assignment.

Although Australia was a penal colony, few convicts served their full sentences in prison. The majority of convicts served most of their sentences under a system known as assignment. Convicts who were assigned worked for private free settlers and for ex-convicts on farms, in private businesses, and as domestic servants. Their employers provided them with food, clothing, and shelter. This system reduced the cost to the British government of maintaining the penal colony. By the 1820’s, assignment had become the major method of convict organization and control. Increasing numbers of settlers with capital to invest arrived in Australia, and assigned convicts provided the cheap labor they needed.

The living conditions of assigned convicts varied enormously. Some convicts had masters who treated them well and offered such incentives as additional rations or tobacco for good behavior and hard work. Others worked for cruel employers who were only interested in getting as much work as possible for the lowest cost. On large estates, male convicts often lived in their own barracks. On smaller farms and in town households, they shared the homes and often the tables of their employers. Female convicts usually did domestic work and lived in their employers’ houses.

Masters were supposed to be responsible for discipline among their convicts and could bring them before the magistrates for any misbehavior or minor crime. Typical offenses included being drunk and disorderly or absent without leave. Flogging (whipping) was the most common punishment. Others included spending time on a road party (work gang) or at a penal station or settlement (a place where convicts were confined apart from the rest of society). However, masters soon discovered that such punishments as flogging did not create good workers.

Convicts were in a vulnerable position. However, they could use a number of methods to change their masters’ demands and behavior or be reassigned to a new master. For example, they could work slowly, pretend not to know their trades, refuse to eat their rations, get drunk, run away, or pretend to be ill. Eventually, they might be sent back to Sydney to be reassigned.

Food.

The early years of settlement were difficult. Settlers had to build shelters and grow their own food. Supplies from overseas often arrived late, and convicts sometimes received reduced rations. To supplement their diet, convicts and soldiers gathered wild vegetables and fished, hunted, and collected oysters. Even after food became more abundant, convicts continued to receive rations.

During the 1820’s, the basic weekly government ration for male convicts was 7 pounds (3.2 kilograms) of beef or 4 pounds (1.8 kilograms) of pork, 7 pounds (3.2 kilograms) of flour or wheaten meal, 3 pounds (1.4 kilograms) of corn meal, and 2 pounds (0.9 kilograms) of sugar. Female convicts were given two-thirds the amount of food that male convicts received. Convicts in the towns frequently sold or traded their rations for other foods or goods.

Some early convicts set up such businesses as bakeries and butcher shops where settlers could buy a variety of foods, including imported ones. Archaeological evidence shows that some convicts cooked meat and vegetables in large pots over open fires indoors. Oysters were extremely popular. Convicts in work gangs and penal settlements had less control over their diet, which lacked fresh produce and tended to provide the same foods over and over. Sometimes government contractors failed to deliver food to these convicts, and the convicts were left hungry.

Clothing.

In the early years of transportation, convicts wore whatever clothing they had brought with them to Australia. The government also provided simple clothing called slops, which resembled the attire of working-class people in Britain.

Beginning in the 1820’s, the government supplied uniforms for convicts on work gangs and at penal settlements. The designs of the uniforms varied. In Van Diemen’s Land in the 1840’s, yellow or yellow-and-black uniforms became common enough that convicts acquired the nickname “canaries.” Some convicts at the Hyde Park Barracks in Sydney wore loose clothing with markings stamped on them. These markings identified the clothing as government property. Assigned convicts continued to wear slops or clothing provided by their masters.

Tickets of leave.

Convicts who behaved well and demonstrated that they could support themselves financially were often given a ticket of leave. Convicts with a ticket of leave still had to serve their sentences, but they could find their own work in the towns or outlying areas. By the 1810’s, however, an assigned convict had to wait three years to obtain a ticket of leave.

Pardons.

The governors of New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land also had the power to pardon convicts before they had served their full sentences. There were two types of pardons—(1) absolute pardons and (2) conditional pardons. Absolute pardons restored a convict’s full rights as a British citizen and allowed him or her to return home. Conditional pardons included the condition that the convict would not return to Britain until his or her original sentence had expired.

Governors issued pardons for a variety of reasons. Good behavior and services performed for the government sometimes earned pardons. Governors also used pardons from time to time as a way to persuade convicts to betray their fellows, who might, for example, be planning to escape. Pardoned ex-convicts were called emancipists. Those who served their full sentences became known as expirees or people who were free by servitude. In common speech, the word emancipist often described any ex-convict.

Escape and rebellion.

Many convicts tried to escape. However, attempts decreased as methods of capture improved and convicts gained more of a stake in the colony. Most escapees were newly arrived convicts or those serving life sentences. Only about 5 percent of convicts who escaped returned to Britain.

The majority of escapees tried to stow away on ships or steal boats and row to other countries. Unknown numbers of escapees died in these attempts. Others made it to such places as China, New Zealand, and Timor. Some escapees discovered new lands or lived with Aboriginal peoples for years. Many were caught, probably betrayed by fellow convicts.

After they had learned the lay of the land, some escaped convicts turned to bushranging (living as an outlaw in Australia’s interior). Bushrangers robbed settlers and travelers in sparsely populated areas of the colony. Bushranging became an especially serious problem in Van Diemen’s Land. In 1825, Governor Thomas Brisbane created the Corp of Mounted Soldiers to pursue bushrangers in New South Wales. In 1826, Lieutenant Governor George Arthur established a mounted police force for the same purpose in Van Diemen’s Land. Captured bushrangers were executed or sent to penal settlements.

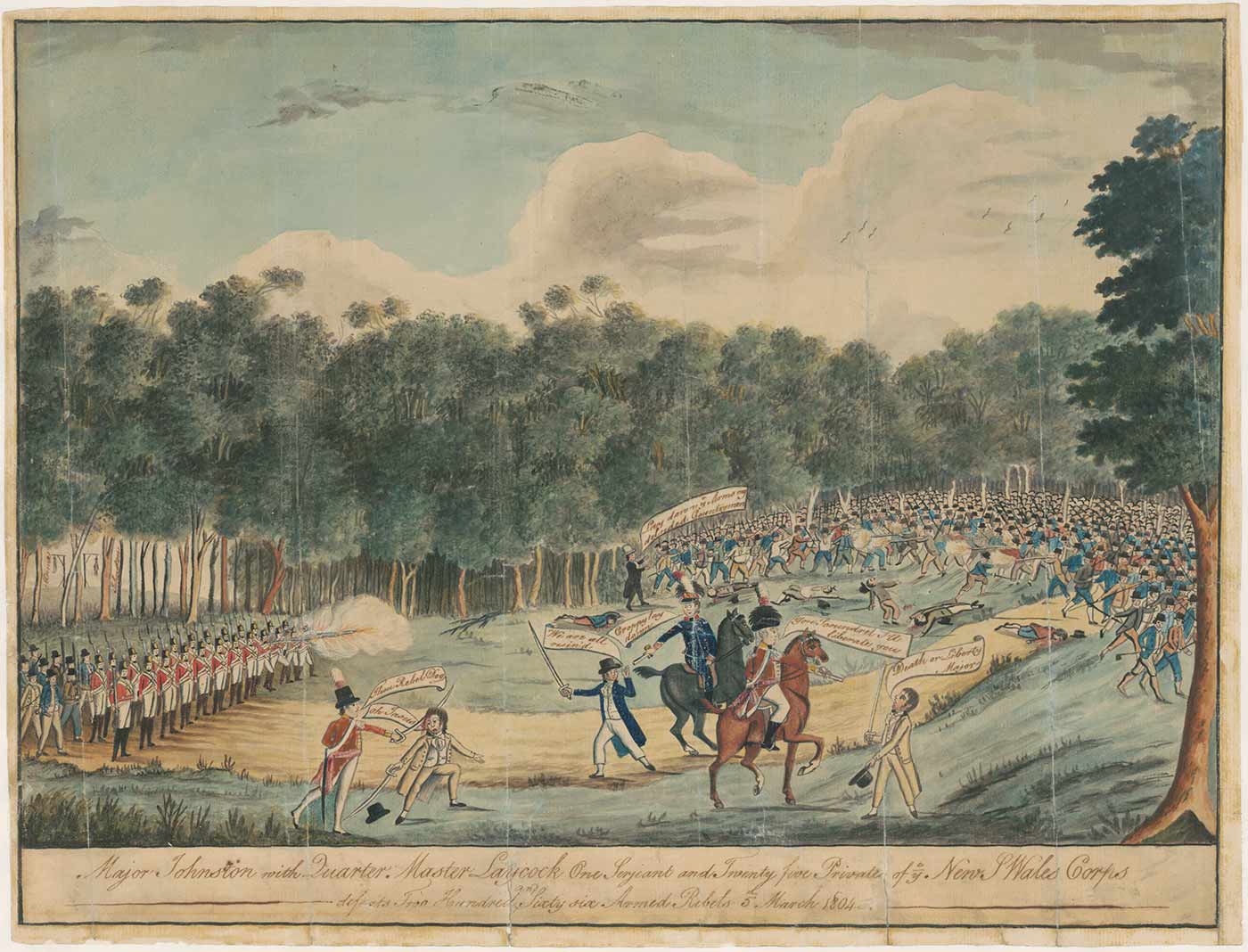

Authorities also feared convict rebellions. In the early 1800’s, Irish convicts carried out a number of plots and rebellions. The most serious rebellion occurred in 1804, when a group of convicts at Castle Hill seized weapons and revolted. They went on a rampage, collecting arms, robbing settlers, and crying, “Liberty or death.” They planned to seize a ship to take them home to Ireland. Soldiers quickly and ruthlessly put down the revolt and many of the leaders were hanged.

Changes in convict life

The early years.

During the early days of Australian settlement, convicts dominated colonial society in New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land. In the 1810’s, convicts made up a majority of the population. However, by 1828, free settlers, native-born Australians, and ex-convicts outnumbered convicts.

In general, convict life before 1822 held more opportunity for advancement than it did later. The early convicts’ fates depended far more on their wealth, skills, and status than on their criminal records.

Before 1822, most convicts lived in private houses, either their own or those of their employers. Hyde Park Barracks, the first convict barracks in Sydney, was not completed until 1819. Convicts who were wealthy, possessed marketable skills, owned businesses, or had families lived independently and worked for themselves.

Newly arrived convicts who lacked friends, money, skills, and status often took such government jobs as brickmaking, clearing brush, construction, or stone quarrying. They were instructed to lodge somewhere in town and turn up for work every morning. These convicts worked mainly according to the task-work system—that is, they completed a certain amount of work each day and then were free to go.

Little thought was given to housing female convicts during the early period of transportation. Some found partners among the male convicts or the officers. Others leased or bought houses and established businesses. There were many pregnancies among convict women. Historical accounts describe their children as healthy and strong. Along with children whom Aboriginal women bore to male convicts, they were the first native-born Australians of European descent.

Increased severity.

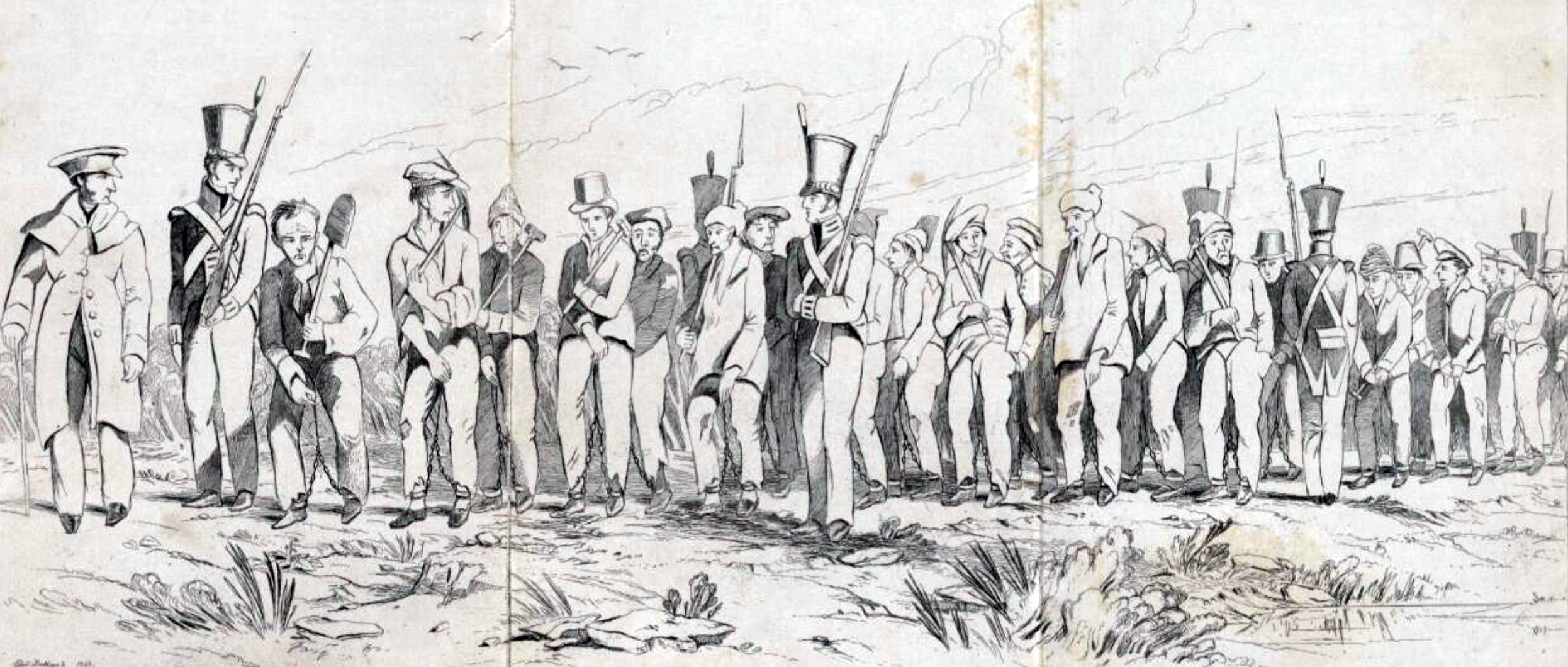

After 1822, the convict system adopted stricter controls and more brutal punishments. British authorities tried to discourage crime by making transportation less appealing. They improved the administration of the convict system, making it easier to monitor, track, and control the convicts. They tightened rules about marriage, convict movement, and work. Children born to convicts were taken away and put into orphanages. Male convicts who committed crimes after arriving in Australia could be sentenced to work for some years in an iron gang (workers chained together to prevent escape) or road party on the country’s roads and bridges. Others were sent to such penal settlements as Macquarie Harbour, in Van Diemen’s Land; Moreton Bay (now Brisbane); Norfolk Island; and Port Arthur. Many of these centers for secondary punishment became infamous for their brutality.

In both New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land, the government established female factories for women convicts who were not assigned to settlers. These institutions, which separated the women from the rest of the community, served a range of purposes. They were jails for women who committed crimes after arriving in Australia. They were also holding centers for women awaiting reassignment. Convicts in the factories worked at various jobs, including the manufacture of cloth. Pregnant convicts also were sent to the factories to deliver their babies.

The experiences of female convicts at the factories were mixed. Some factories were dirty, oppressive, and overcrowded. Troublesome convicts might be punished by having their heads shaved. However, factories were also places where women found shelter and formed friendships. Many inhabitants of the female factories left to marry settlers, especially ex-convicts.

The end of transportation

New South Wales.

Transportation and assignment had powerful opponents in Britain who likened the convict system to slavery. During the 1830’s, their campaigns led to an official investigation known as the Molesworth Committee. Its findings were extremely critical of the convict system. As a result, the British suspended transportation to New South Wales in 1840.

The British government tried to reintroduce transportation to New South Wales several times until about 1850. Such attempts met with fierce opposition from many colonists, particularly from free immigrants, whose numbers had risen steadily in the 1830’s. Antitransportation leagues formed and campaigned against transportation. In 1849, hostile crowds greeted the convict ships Hashemy and Randolph when they tried to land convicts in Sydney.

Van Diemen’s Land.

In 1842, the British government replaced assignment with a new system of convict organization in Van Diemen’s Land. Known as probation, it was meant to reform as well as punish. About 30,000 convicts were transported to Van Diemen’s Land under the new system. On arrival, male convicts were assigned to probation gangs, which lived at facilities called probation stations. Probation gangs constructed such public works as bridges, buildings, and roads. Female convicts went to the female factories, where they had little to do.

After two years, if the convicts had behaved well, they received probation passes. The passes allowed convicts to work for private employers and earn wages. However, there was not enough work for all the convicts, and free settlers complained about their numbers. Continued good behavior earned a ticket of leave, which had fewer restrictions than a probation pass. Finally, convicts could earn a pardon. Authorities could withdraw tickets of leave and probation passes for bad behavior. The probation system eventually proved itself a failure, and the government suspended it in 1846.

Over time, opposition to transportation grew in Van Diemen’s Land, and a local antitransportation league attracted a large following. In 1852, transportation to the eastern colonies was abolished. The last convicts were transported to Hobart in 1853. However, transportation to Norfolk Island continued until 1856.

Western Australia.

The convict system in the colony of Western Australia bore little resemblance to that in New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land. It began in 1850 at the request of the Western Australian government and continued until 1868. Officials thought that convicts could stimulate the economy by building roads and other public works and by providing a cheap source of labor, as they had done in the east. In fact, one of the convicts’ first tasks was to build a jail at Fremantle large enough to house themselves. But the Western Australian economy did not develop as quickly as the government and the colonists had hoped it would.

Convicts were transported to Western Australia after serving part of their sentence in Britain. On arrival, they were employed on public works, in conditions similar to those that had governed probation in Van Diemen’s Land. With good behavior, convicts received a ticket of leave. Further good behavior earned a conditional pardon, the condition being that the recipient could not return to Britain. Although later Western Australians often did not like to admit it, the convicts put the colony on a sound economic footing.

The convict legacy

In Australia, many convicts acquired property, some started families, and a few became rich. But for others who were mentally or physically weak, unskilled, or rebellious, the convict system was oppressive. This was especially true in the later period, when the government controlled every important aspect of convict life and the system could be cruel and violent. These convicts had limited opportunities to create a new life in Australia.

Some people argue that the convict period shaped Australia’s character and that the egalitarianism (equality) often attributed to Australians and the notion of mateship (comradeship) have their roots in this period. Others say that convict history caused Australians to distrust authority and dislike police. The large number of male convicts in Australia fostered a male culture that later came to be considered characteristically Australian.

There is no doubt that convicts played a vital role in establishing settlement in New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land. Convict enterprise and cheap convict labor helped build the colonial economies. Convicts were essential to the establishment of certain industries, particularly the wool industry. Convict labor revived the economy of Western Australia and gave it a firm base.

But the longest and most noticeable legacy of the convict period was shame and silence. For over a hundred years, Australians suppressed knowledge of the convicts, destroyed records of them, and never spoke about their convict ancestors. Not until the 1970’s, which were characterized by a rising national feeling and an interest in national history, did Australians come to acknowledge the convicts’ contributions.