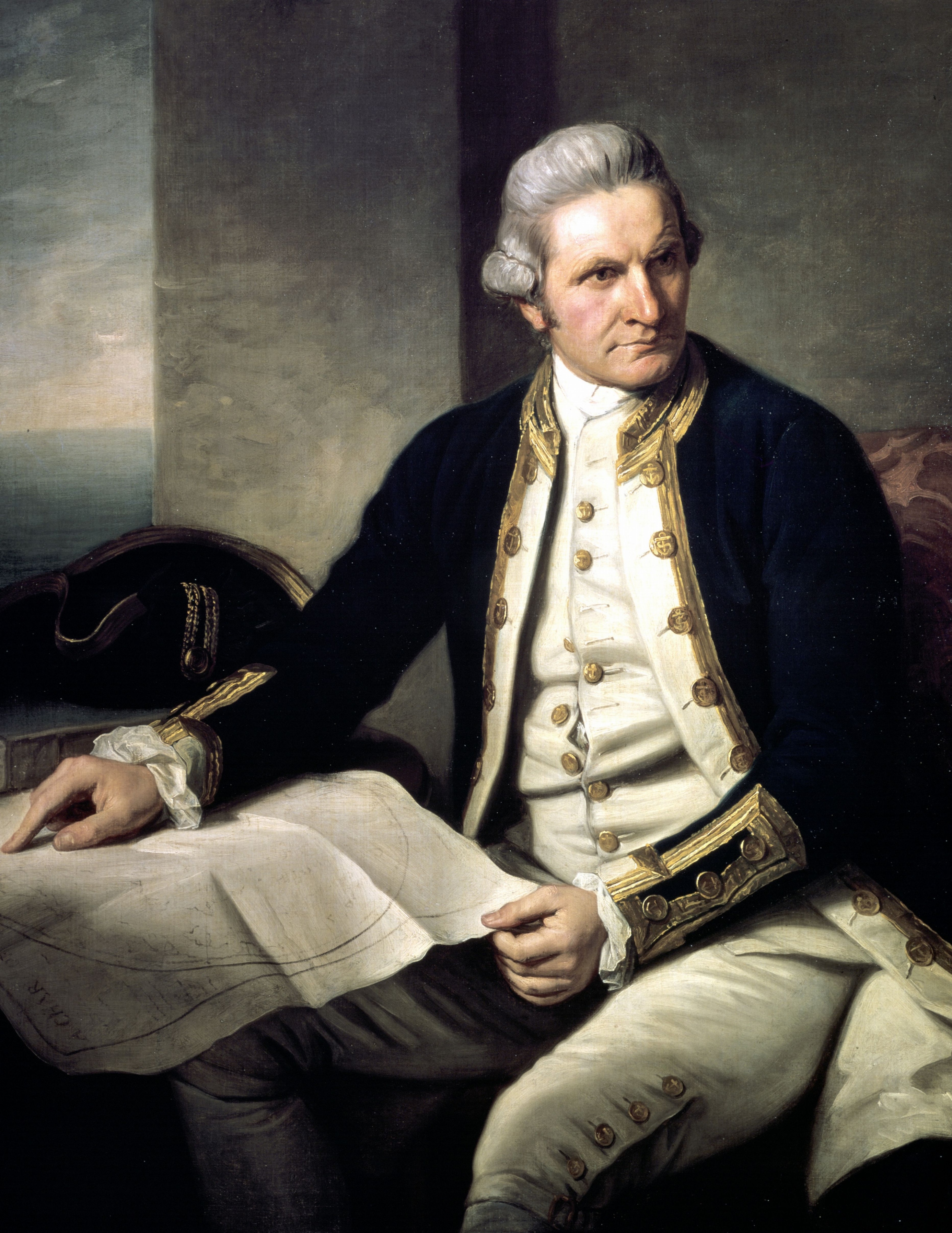

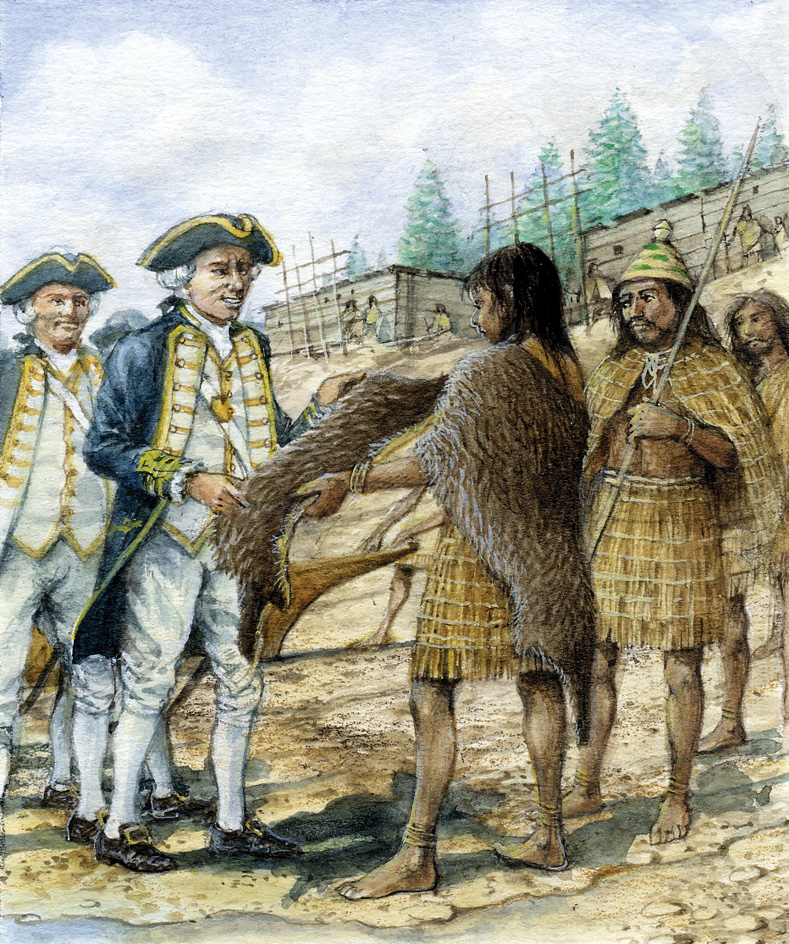

Cook, James (1728-1779), a British naval captain and navigator, was one of the world’s greatest explorers. He commanded three voyages to the Pacific Ocean that greatly increased knowledge of the world’s geography. Cook had an outstanding ability to accurately determine where newly encountered lands should be placed on maps. He also prevented on his ships the high death tolls from disease that had long been common on sea voyages. In addition, he was known for his peaceful relations with the peoples he came across on his expeditions.

A number of the officers Cook trained became explorers themselves. They copied him in the care of their crews, the accuracy of their mapping, and their respectful dealings with the peoples they met. Cook’s example was thus perhaps as important as his own achievements.

Early life.

Cook was born in Marton, England, near Middlesbrough, on Oct. 27, 1728. He began working as an apprentice for a shipowner in his late teens and quickly became an excellent sailor. In 1755, Cook joined the British navy. The Seven Years’ War between Britain (now the United Kingdom) and France broke out the following year. During the war, Cook served in Canada, where he learned surveying, mathematics, and astronomy. After the war ended in 1763, he was sent to survey part of Canada’s eastern coast.

First Pacific voyage.

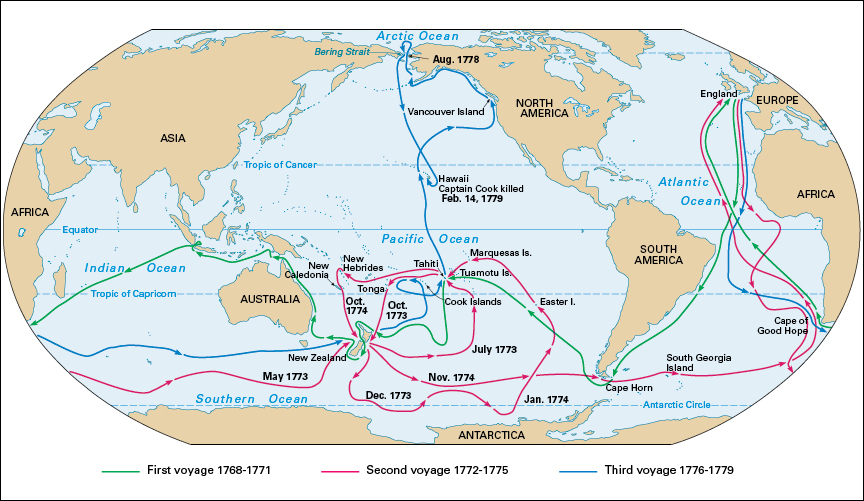

Cook’s work was so highly regarded that the navy chose him to lead an important expedition in 1768. His ship, the Endeavour, sailed to the South Pacific island of Tahiti. From there, Cook’s crew watched the planet Venus as it moved across the face of the sun. Scientists wanted to observe this movement from several places on Earth, believing that the distance from Earth to the sun could then be calculated. Cook explored Tahiti and nearby islands for three months, collecting information about the Tahitians and their culture.

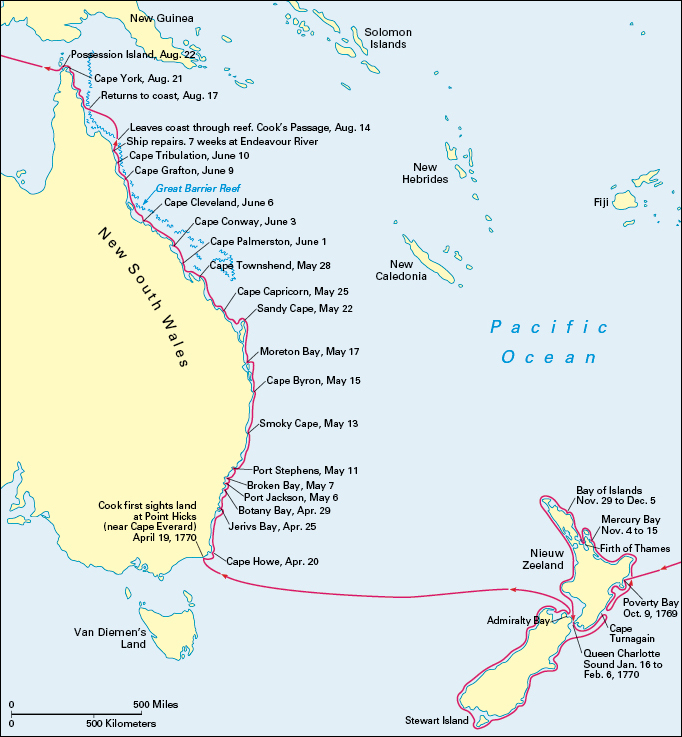

Cook then sailed south in search of a large continent that some scientists thought must exist in the South Pacific. But he did not find it. He went to New Zealand, charted its coastline, and encountered the Māori people there. He then continued west toward what is now called Australia and mapped that continent’s east coast.

One of Cook’s great successes was preventing major outbreaks of scurvy on his voyages. Scurvy is a disease caused by a lack of vitamin C. It can be prevented by eating such foods as fresh fruits and vegetables. Because Cook fed his sailors appropriately, no one died from scurvy during the three-year voyage of the Endeavour.

Second Pacific voyage.

In 1772, Cook was sent on another voyage, this time with two ships, the Resolution and the Adventure. The purposes of this voyage were to search farther for the suspected South Pacific continent and to test a new navigational instrument called a chronometer.

Cook sailed far to the south and became the first navigator to cross the Antarctic Circle. The sight of huge icebergs convinced him that a polar continent must exist. But ice and severe weather prevented him from getting close enough to see it.

During the voyage, Cook visited New Zealand three times. He also located and mapped islands that earlier explorers had failed to place accurately on maps. He visited Easter Island, the Marquesas Islands, the Tuamotu Islands, New Caledonia, Tonga, New Hebrides (now Vanuatu), the Cook Islands, and Tahiti.

Final voyage.

In 1776, the British government decided that Cook should lead a third voyage. He was given two ships, the Resolution and the Discovery. The purpose of this voyage was to find a Northwest Passage—a northern sea route between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. Explorers had been looking for such a passage for more than 200 years.

On the way to the North Pacific, Cook revisited New Zealand, Tonga, and Tahiti. He and his crew also became the first Europeans definitely known to have visited Hawaii. In 1778, Cook explored the northwest coast of North America and sailed into the Arctic Ocean.

Cook returned to Hawaii for the winter. On Feb. 14, 1779, he was killed in a dispute between his men and the Hawaiians. Cook’s ships tried to continue the voyage, but little more was accomplished. The ships returned to England in 1780.