Crusades were Christian military expeditions and religious wars proclaimed by the pope. They were organized mainly to defend Christians and to recover or defend territories that Christians believed belonged to them by right. The Crusades, waged by Western Europeans, took place from the late 1000’s to the 1500’s. The original goal of the Crusades was to gain and keep control of Palestine, also called the Holy Land. This region was important to Christians because it was where Jesus Christ had lived. Palestine lay along the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea, and Muslims had taken control of it from Christians. In the First Crusade, Christians recaptured Palestine. During later Crusades, they fought to protect Palestine or to recover parts of it that had again been lost to Muslim forces.

According to the church, crusading counted as an act of penance—that is, payment to God for sins committed. From the late 1000’s to the late 1300’s, the Crusades were a popular religious activity, attracting thousands of nobles, knights, peasants, and townspeople. Not all the crusaders joined the expeditions for religious reasons. Some hoped to gain power, territory, and riches. But most survivors returned home with little material profit.

Even after 1291, when Muslims regained control of the last Christian territory in Palestine, Crusades continued in the eastern Mediterranean region. They also took place in such areas as the Iberian Peninsula, the lands surrounding the Baltic Sea, Eastern Europe, and even within Western Europe itself. The crusaders’ enemies included Muslims and other non-Christians, Greek and Russian Orthodox Christians, and even Roman Catholics considered to be political threats to the church.

The word crusade comes from the Latin word crux, meaning cross. Members of the many expeditions sewed the symbol of the cross of Christ on their clothing. “To take up the cross” meant to become a crusader.

How the Crusades began.

During the A.D. 500’s, the Byzantine Empire—a Christian empire centered in southeastern Europe—controlled much of the land bordering the Mediterranean Sea (see Byzantine Empire). This area included southeastern Europe, Asia Minor (now part of Turkey), Palestine, Syria, Italy, and parts of Spain and North Africa. In the 600’s, Arab Muslims conquered Palestine, including Jerusalem. Most of the new Arab rulers allowed Christians to visit the shrines in the Holy Land (see Jerusalem).

Starting in the 900’s, Christian pilgrimages from Western Europe to Palestine became increasingly common, and the attachment of Western Christians to a place they considered to be holy grew. Christians came to believe it was a disgrace that Muslims controlled the sites of Christ’s Crucifixion and Resurrection.

During the 1000’s, Seljuk Turks from central Asia conquered much of the Middle East, including Palestine, Syria, and most of Asia Minor. The Seljuks, who were Muslims, crushed the Byzantines in the Battle of Manzikert in Asia Minor in 1071. See Seljuks.

In 1095, Byzantine Emperor Alexius I Comnenus asked Pope Urban II for assistance in fighting the Seljuk Turks. Urban agreed to help. He wanted to defend Christianity against the Muslims and to recover the holy places.

In the autumn of 1095, Urban held a meeting of church leaders in Clermont, France. At this Council of Clermont, Urban called for a crusade. He gave a stirring sermon, urging European Christians to stop fighting among themselves and recapture the Holy Land from the Muslims. He promised the crusaders both spiritual and material rewards for their work. The crowd reportedly responded with shouts of “God wills it!” An intense desire to fight for Christianity gripped Western Europe, and thousands of people joined the cause. See Urban II.

The First Crusade

(1096-1099). Following Urban’s call for a crusade, a preacher known as Peter the Hermit and a knight called Walter the Penniless led groups that rushed ahead of the official expedition. These crusaders made up the first of several untrained and undisciplined groups that became known as the Peasants’ Crusade. They demanded free food and shelter as they traveled through eastern Europe toward Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey). Stirred by an intense feeling against non-Christians, some groups in the Peasants’ Crusade—and some later crusaders—also killed many Jews. Because the members of the Peasants’ Crusade often stole what they wanted, many were killed by angry Europeans. Muslims killed most of the rest in Asia Minor. See Peter the Hermit.

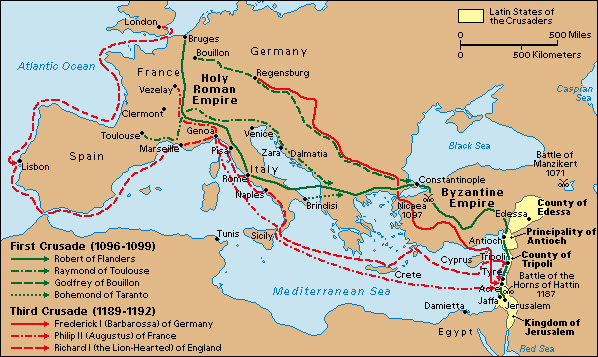

The main armies sent by Urban consisted chiefly of well-trained French and Norman knights. The key leaders included Godfrey of Bouillon, Raymond of Toulouse, Robert of Flanders, Robert of Normandy, Stephen of Blois, and Bohemond of Taranto. At Constantinople, Byzantine forces joined the crusaders. In 1097, the combined army took the city of Nicaea, in what is now northwest Turkey.

Then the army divided, and the Western Europeans marched toward Jerusalem, fighting many bloody battles along the way. The most difficult was the siege of Antioch, in northern Syria (now in Turkey). Many crusaders died there, in battle or from hunger, and many others deserted. After Antioch had been captured, the crusaders were attacked there by the Seljuks. However, the crusaders discovered a lance said to be the one that was thrust into the side of Jesus on the cross. Inspired by this discovery, the crusaders won a great victory. The Europeans arrived at Jerusalem in the summer of 1099. They recovered the city after six weeks of fighting. Most of the crusaders then returned home. The leaders who stayed divided the conquered land into four crusader states—the County of Edessa, the Principality of Antioch, the County of Tripoli, and the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

The Second Crusade

(1147-1149). In 1144, the Turks conquered the County of Edessa. The threat to the other crusader states brought about the Second Crusade. The spirited preachings of the French religious leader Bernard of Clairvaux inspired Western Europeans to defend the crusader states against the Muslims. See Bernard of Clairvaux, Saint.

King Louis VII of France and King Conrad III of Germany led the armies of the Second Crusade into Asia Minor. But their armies did not cooperate, and the Muslim forces defeated them before they reached Edessa.

The Third Crusade

(1189-1192). The Muslims continued to attack the Christians in the Holy Land. By 1183, Saladin, the sultan of Egypt and Syria, had united the Muslim areas around the crusader states. In 1187, Saladin easily defeated a Christian army at the Battle of the Horns of Hattin and triumphantly entered Jerusalem. Only the coastal cities of Tyre, Tripoli, and Antioch remained in Christian hands. See Saladin.

The loss of Jerusalem led to the Third Crusade. The important European leaders of the Third Crusade included the German emperor Frederick I (called Barbarossa), King Richard I (the Lion-Hearted) of England, and King Philip II (Augustus) of France.

Frederick drowned in 1190 on his way to the Holy Land. Quarrels among Richard, Philip, and other leaders limited the crusaders’ success. The Europeans conquered the Palestinian port cities of Acre (now Akko) and Jaffa in 1191. But after the capture of Acre, Philip returned home. Richard tried to recapture Jerusalem. He failed, but his recovery of the Palestinian coastline allowed the Kingdom of Jerusalem to exist for another century. Before Richard left for home, he negotiated a treaty with Saladin. As a result of this treaty, the Muslims let Christian pilgrims enter Jerusalem freely.

The Fourth Crusade

(1202-1204). Crusading reached the height of its popularity in the 1200’s. There was hardly a year during the century when crusaders were not fighting somewhere. The Fourth Crusade, which took place at the beginning of the 1200’s, resulted from the failure of the Third Crusade to recapture Jerusalem. The crusaders became involved in affairs of the Byzantine Empire, however, and failed to reach their original goal.

Pope Innocent III persuaded many French nobles to take part in the Fourth Crusade, which he thought should go to the Holy Land. But the Crusade’s leaders decided to attack Egypt instead in order to split Muslim power. The crusaders bargained with traders from Venice, a powerful Italian port city, to take them by ship to Egypt. Only about a third of the expected number of crusaders arrived at Venice, and they could not pay the costs of the ships. But the Venetians offered to transport the crusaders if they helped attack Zara, a city in what is now Croatia. The crusaders accepted the offer.

Meanwhile, a refugee Greek prince named Alexius claimed that his father, Isaac, was the rightful Byzantine ruler. The crusaders agreed to help him regain the empire in return for money and other aid in reconquering the Holy Land. In 1203, they camped outside Constantinople, briefly tried to capture the city, and made Isaac and Alexius co-emperors. But Alexius could not fulfill his promises to the crusaders. In 1204, the crusaders captured Constantinople and put Count Baldwin of Flanders on the Byzantine throne. This Latin Empire of Constantinople lasted until 1261.

The Children’s Crusade

(1212) was one of a number of People’s Crusades—popular crusades that were not proclaimed by the pope and in which most of the crusaders were poor people. The Children’s Crusade began after thousands of poor people, including boys and girls from about 10 to 18 years old, became convinced that they could recover Jerusalem. They believed God would deliver the Holy City to them because they were poor and faithful. Children from France formed one part of the group, and children from Germany the other. They expected God to part the waters of the Mediterranean Sea so that they could cross safely to Jerusalem.

None of the children reached the Holy Land. Many starved or froze to death during the long march south to the Mediterranean. When the expected miracle did not occur, some of the youngsters who survived the terrible journey to the sea got aboard ships going to the East. These children either were drowned in storms at sea or sold into slavery by the Muslims.

Other Crusades

continued in the 1200’s. In the Fifth Crusade (1217-1229), the Christians continued the strategy of concentrating their efforts on Egypt, which they considered to be a key for winning Palestine. They captured the port of Damietta, but soon had to give it up in exchange for a truce. The Emperor Frederick II of the Holy Roman Empire later negotiated a peace with the Muslim sultan, who gave Jerusalem to the Christians.

Jerusalem remained Christian until the Muslims seized it again in 1244. The fall of Jerusalem caused King Louis IX of France (Saint Louis) to lead a Crusade from 1248 to 1254. Like earlier crusaders, he also tried to win the Holy Land by attacking Egypt. But his expedition became disorganized, and the Muslims captured Louis and most of his army. The Muslims freed them in exchange for a ransom and the return of Damietta, which Louis had captured. Before returning to France, Louis spent four years in the Holy Land trying to strengthen the Christian forces there. In 1270, he led another Crusade against the Muslims. He landed his army at Tunis, in northern Africa. But he died soon afterward when disease broke out among his troops. See Louis IX.

Meanwhile, in the East, the Muslims continued to gain Christian territory. They captured Antioch in 1268. Finally, in 1291, they seized Acre, the last Christian center in Palestine.

Concern about recovering the Holy Land remained strong in the 1300’s. But in that century, the Ottoman Turks, who were Muslims, became a serious threat to Christian Europe. The crusaders shifted their attention from the recovery of Jerusalem to the defense of Europe. The Byzantine Empire fell to the Ottomans in 1453, and by 1500, Muslims were occupying far more territory in Europe than the Christians had held in the East. But the crusaders did succeed in defending much of Western Europe from the Muslims and in recapturing Spain and Portugal from them. In the 1600’s, Western Europeans began to recover parts of southeastern Europe.

Results of the Crusades.

The crusaders failed to accomplish their main goals. They recaptured the Holy Land for a time but could not establish lasting control over the area. Western European and Eastern European Christians united to fight the Muslims. But relations between the Christians of Western Europe and the Orthodox Christians of the East became bitter. The Fourth Crusade, during which Western crusaders captured and partially destroyed Constantinople, played a major role in driving the two groups apart. Some bitterness has continued to the present day. In addition, the crusaders’ persecution of European Jews marked the beginning of a long period of Jewish martyrdom (death for a belief).

But the Crusades also enriched European life. For example, they stimulated economic growth by increasing trade between cities bordering the Mediterranean Sea. The Italian cities of Venice, Genoa, and Pisa profited by carrying crusaders and supplies to the Middle East. These cities gained trading privileges in territories conquered during the Crusades. The cities became rich and powerful handling trade in Asian goods that passed through the conquered territories on the way to Europe.

Western Europeans also learned how to build better ships and make more accurate maps during the Crusades. They began to use magnetic compasses to tell directions. The Crusades were only modestly important compared to the great commercial expansion or the rise of monarchies in Western Europe. But they seemed extremely important to the people of the crusading era.

Historians once thought the crusaders who returned to Europe introduced Westerners to Eastern goods and ways of life. They thought that this contact greatly influenced Western life. As a result of the Crusades, they argued, Europeans were introduced to such items as sugar, silk, velvet, and glass mirrors. But modern historians reject these arguments. They point to a wide amount of interchange between Muslims, Byzantines, and Europeans long before the Crusades.