Czechoslovakia was a country in central Europe from 1918 until 1992. The Czech Republic and Slovakia took its place in 1993.

Czechoslovakia was home to two closely related Slavic peoples, the Czechs and the Slovaks. Most of the Czechs lived in the western part of the country, in the regions of Bohemia and Moravia. The Slovaks lived primarily in Slovakia, an area in the east.

Germany invaded Czechoslovakia in 1939 and occupied the country for most of World War II (1939-1945). In 1948, Communists began ruling Czechoslovakia. In 1989, hundreds of thousands of citizens participated in demonstrations calling for an end to Communist rule. In response, the Communist government resigned and a non-Communist government came to power.

Disagreements soon broke out between Czechs and Slovaks over how to reform the country’s government and economy. In mid-1992, Czech and Slovak leaders decided to break Czechoslovakia into two separate nations. On Jan. 1, 1993, the Czechs formed the Czech Republic and the Slovaks formed Slovakia to replace Czechoslovakia.

Early history.

Celtic and Germanic tribes lived in what became Czechoslovakia more than 2,000 years ago. Slavic tribes settled in the region by about A.D. 500. Several of the tribes united to form a state in the 800’s. The state became the core of the Great Moravian Empire, which soon covered much of central Europe. Hungarian tribes conquered the empire in 907. Hungarians then ruled Slovakia for about the next 1,000 years.

In 1212, Bohemia became a semi-independent kingdom within the Holy Roman Empire, a German-based empire in western and central Europe. In 1526, the Austrian Habsburgs (or Hapsburgs) began ruling Bohemia. In time, Bohemia lost most of its self-governing powers. In the late 1700’s, Czech intellectuals worked to create a greater sense of national identity among Czechs. By the mid-1800’s, a movement for self-government had gathered strength. A similar movement grew in Slovakia. But Hungarian rulers put down the Slovak movement. In 1867, Austria and Hungary formed a monarchy called Austria-Hungary.

The formation of Czechoslovakia.

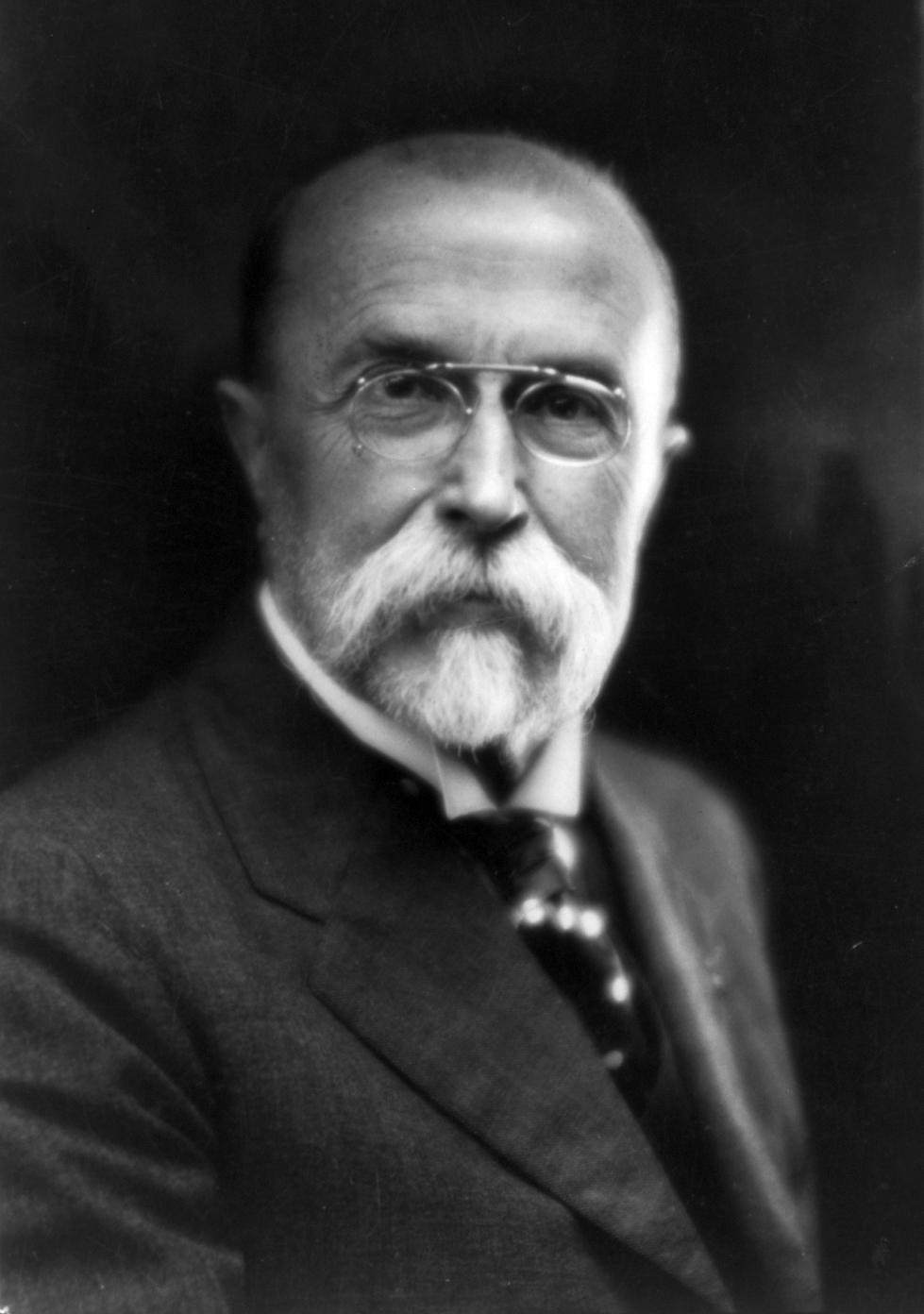

During World War I (1914-1918), two leading Czech nationalists—Eduard Beneš and Tomáš G. Masaryk—worked to gain foreign support for the idea of an independent nation made up of Czechs and Slovaks. At the end of World War I in 1918, Austria-Hungary collapsed, and Czechoslovakia was created from part of it. The Czechoslovak Constitution established the country as a democratic republic. Masaryk served as president from 1918 until 1935, when Beneš succeeded him. In 1919, Ruthenia, a region east of Slovakia, became part of Czechoslovakia.

Although Czechs made up less than 50 percent of the population of Czechoslovakia, they dominated the economy and government. During the 1920’s and 1930’s, many Slovaks grew resentful of Czech control. The Sudeten Germans (Germans who lived in the Sudetenland, the border regions of western Czechoslovakia) also became dissatisfied with Czech dominance.

The Munich Agreement.

German dictator Adolf Hitler encouraged the Sudeten Germans to demand self-rule. He threatened war with Czechoslovakia if the demand was not met. In 1938, the leaders of the United Kingdom and France agreed to Hitler’s demand and signed the Munich Agreement, a pact that forced Czechoslovakia to give the Sudetenland to Germany. Later that year, Hungary and Poland claimed other parts of Czechoslovakia. In March 1939, a few months before World War II broke out, Germany seized the rest of Czechoslovakia. Slovakia became a separate republic under German control. Hitler made Bohemia and Moravia a German protectorate.

German occupation during the war brought widespread suffering to Czechoslovakia. More than 250,000 people, including almost all the country’s Jews, were killed.

Eduard Beneš, who had resigned as president in 1938, formed a government-in-exile in London during the war. He cooperated with both Western powers and the Soviet Union. In 1943, he signed a treaty of friendship and cooperation with the Soviet government. By 1945, the Soviet army had freed most of Czechoslovakia from the Germans. United States troops liberated parts of Bohemia. After World War II ended in 1945, the government-in-exile returned, and all foreign troops were withdrawn from Czechoslovakia. The same year, Czechoslovakia gave Ruthenia to the Soviet Union, and the Sudetenland was returned to Czechoslovakia. Over 2 million Germans were expelled from the Sudetenland.

Communist rule.

Beneš formed a coalition government to lead postwar Czechoslovakia. Communists held many important positions in the new government. With popular support, the government put many of the country’s major industries under state control. It also forced hundreds of thousands of Germans and Hungarians living in Czechoslovakia to leave.

In national elections in 1946, the Communist Party received more votes than any other party. The Communist Party chairman, Klement Gottwald, became prime minister of Czechoslovakia. In February 1948, the Communists caused a crisis that led to the resignation of non-Communist government ministers. The Communists then formed a government dominated by Communists. Beneš resigned a few months later, and Gottwald succeeded him.

Czechoslovakia’s Communist leaders copied the Soviet model of political organization and economic development. The Communist Party became the only powerful political party. The government managed all aspects of the economy. Farmers were forced to join either state farms or collectives. The government owned and operated state farms. On collective farms, farmworkers jointly owned the farm equipment and property.

Gottwald remained president of Czechoslovakia until 1953, when Antonín Zápotocký succeeded him. Antonín Novotný became president in 1957.

The 1960’s.

During the early 1960’s, Czechoslovakia’s agricultural and industrial production dropped, and there were shortages of food and other goods. Even members of the Communist Party criticized the government’s inability to reverse the economic decline. At the same time, the country’s intellectuals called for more freedom of expression, and many Slovaks renewed their efforts to gain recognition for Slovak rights. In 1968, the Communists removed Antonín Novotný as party leader. Alexander Dubček, a Slovak, became the party leader, and Ludvík Svoboda became the country’s president.

Under Dubček, the government introduced a program of liberal reforms. These reforms included more freedom of the press and increased contacts with non-Communist countries. Dubček won popularity among Czechoslovakia’s people for the reforms, known as the Prague Spring. But leaders of the Soviet Union and other European Communist nations feared that Dubček’s program would weaken the party’s control in Czechoslovakia. They also feared that people in other Communist countries would demand similar reforms. The reform movement ended when troops from the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, East Germany, Hungary, and Poland invaded Czechoslovakia in August 1968. The Soviet troops remained, but the other troops withdrew by late 1968.

In April 1969, the Czechoslovak Communist Party replaced Dubček with Gustáv Husák, another Slovak Communist. Thousands of people who had been active in the reform movement either resigned or were removed from the party. In 1975, Husák succeeded Svoboda as president and also continued to serve as Communist Party leader. Under Husák, Czechoslovakia remained a tightly controlled Communist state and a loyal ally of the Soviet Union.

The Velvet Revolution.

In 1987, Husák resigned as Czechoslovakia’s Communist Party leader. He remained president. Miloš Jakeš succeeded Husák as party leader. In November 1989, hundreds of thousands of people gathered in the streets of Prague to demand changes in the government and greater political, economic, and civil freedoms. The demonstrations were followed by general strikes and demonstrations by people across the country. In response to the protests, Communist Party leader Jakeš resigned and Karel Urbánek replaced him. In addition, Czechoslovakia’s Communist-controlled Federal Assembly voted to end Communism’s leading role in the Czechoslovak government and society.

In December, Marián Čalfa, a liberal Communist, became prime minister and later left the Communist Party. Non-Communists gained control of most key Cabinet ministries. Husák then resigned under pressure. The Federal Assembly elected Václav Havel, a non-Communist playwright, to succeed Husák. The end of Communist rule was so smooth and peaceful that it became known as the Velvet Revolution.

The new government worked to increase free enterprise in Czechoslovakia. It restored such civil liberties as freedom of religion, speech, and the press. It also called for free elections, which were held in June 1990. In the elections, the Civic Forum—the Czech party that had emerged in November 1989 to lead the Velvet Revolution—and its Slovak ally, Public Against Violence, won a majority of seats in the Federal Assembly. The Assembly reelected Havel president in July 1990. The Soviet Union withdrew its troops from Czechoslovakia in June 1991, six months before it broke apart.

In 1992, Czechoslovakia’s government took a large step toward establishing an economy based on free enterprise. It began to sell shares of stock in companies it had owned. As a result, more than 1,000 companies became privately owned. In addition, hundreds of thousands of new privately owned businesses were established.

However, the move toward a free-enterprise economy caused far more unemployment in Slovakia than in the Czech areas. Tensions between the Czechs and Slovaks prevented the adoption of a new constitution and slowed economic reform. Although many Czechs and Slovaks wanted to remain united, the prime ministers of the Czech Republic and Slovakia began negotiating the breakup of Czechoslovakia in June 1992. Havel resigned, saying he did not want to preside over the breakup of his country. On Jan. 1, 1993, the independent nations of the Czech Republic and Slovakia were created to replace Czechoslovakia.