De Gaulle, << duh GOHL or duh GAWL, >> Charles André Joseph Marie (1890-1970), became the outstanding French patriot, soldier, and statesman of the 1900’s. He led French resistance against Germany in World War II (1939-1945) and restored order in France after the war. He guided the formation of France’s Fifth Republic in 1958 and served as its president until his resignation in 1969.

As president, de Gaulle led his country through a difficult period in which France granted independence to Algeria and other overseas territories. He fashioned a new role for France in Europe based on close association with a former enemy, Germany. His leadership restored political and economic stability, and again made France one of Europe’s leading powers. De Gaulle provided France with a successful constitution, political system, and foreign policy.

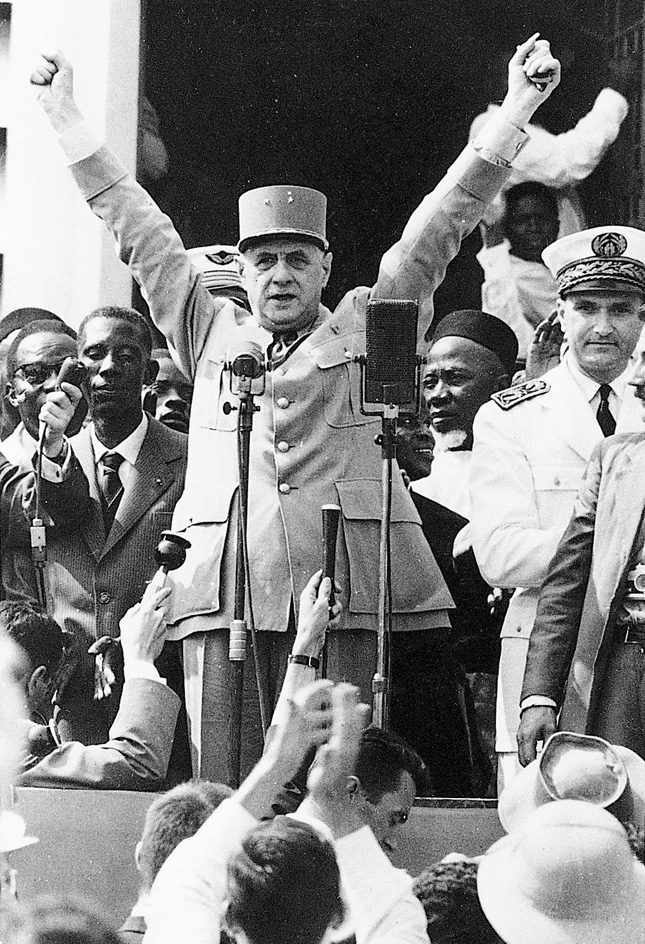

De Gaulle became a symbol of France throughout the world. Even his name suggested Gaul, the ancient Roman name for an area that is now mainly France. An imposing figure 6 feet 4 inches (193 centimeters) tall, de Gaulle was stern and aloof. Some people thought him stubborn and arrogant. But de Gaulle had a deep love for France, and he believed that it was his destiny to make France a leader in world affairs.

Early life.

De Gaulle was born Nov. 22, 1890, in Lille. His father, Henri, served as an officer in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) and then taught philosophy, literature, and mathematics. His mother, Jeanne Maillot de Gaulle, came from a literary and military family.

With his sister and three brothers, Charles grew up in an atmosphere that was both military and religious. As a boy, he enjoyed reading stories of famous French battles. When he played soldiers with his friends, Charles always had to be “France.” After studying at the College Stanislas, a private Roman Catholic school in Paris, de Gaulle served a year in the infantry. He graduated with honors in 1911 from a leading French military school, the École Spéciale Militaire de Saint-Cyr.

During World War I (1914-1918), de Gaulle was wounded four times. He was captured at Verdun in 1916. After the war, he served with the French Army in Poland, then taught military history at St. Cyr for a year.

In 1921, he married Yvonne Vendroux, a devout Roman Catholic. They had a son and two daughters. Yvonne de Gaulle followed her husband wherever his duties took him.

Between World Wars I and II, de Gaulle held various military commands and taught at France’s École Supérieure de Guerre (War College). His book The Edge of the Sword (1932) stressed the importance of powerful leadership in war. In The Army of the Future (1934), he outlined the theory of a war of movement, in which tanks and other mechanized forces would be used. Most French military leaders resisted this theory. However, some German officers studied it and applied similar tactics in World War II.

Leader of the Free French.

After the Germans invaded France in May 1940, de Gaulle was put in charge of one of France’s four armored divisions. He became undersecretary for war in June. But just days later, on June 22, France surrendered to Germany.

De Gaulle, then a general, escaped to London. He refused to accept the surrender. Nor would he recognize the authority of Marshal Henri Philippe Pétain, his former regimental commander and patron, who headed the Vichy government that cooperated with the Germans (see Pétain, Henri Philippe). For this, a French military court sentenced de Gaulle to death. De Gaulle declared that France had lost a battle but not the war. He broadcast such messages to France as: “Whatever happens, the flame of French resistance must not and shall not go out.” Throughout the war, his broadcasts stirred French patriotism and kept French resistance alive.

De Gaulle organized the Free French forces in the United Kingdom and in some of the French colonies. In September 1941, he became president of the French National Committee in London. Although de Gaulle at times faced opposition from British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt, he emerged as the leader of France’s provisional government. De Gaulle triumphantly entered Paris with the Allies in August 1944.

Peacetime leader.

De Gaulle got the machinery of government working again during the next 14 months. But France’s left-wing parties did not support him, and he resigned in January 1946. He bitterly opposed the Constitution of 1946 because it did not provide a strong executive power. In 1947, he organized a new political movement, the Rally of the French People, that he hoped would allow him to return to power. But it lost strength after the elections of 1951.

De Gaulle retired to his country home to write his memoirs. He watched as the political situation in France grew worse, hoping for another chance to lead.

The Fifth Republic.

Finally, in May 1958, the call came. France stood on the verge of civil war. Dissatisfied French officers, afraid they would lose the government’s support against the Algerian rebels, seized power in Algiers. De Gaulle emerged as the best hope to prevent domestic chaos. In June, he accepted President Rene Coty’s request to form a government, but on the condition that he have full powers for six months.

De Gaulle had a new constitution drawn up that established the Fifth Republic. It provided broad powers for the president, who was to be elected for seven years by an electoral college of 80,000 public officials. French voters approved the plan, and the electoral college chose de Gaulle as president in December 1958.

As president, de Gaulle acted with great firmness. After another revolt in Algeria in 1960, he arrested French officers there who had formerly supported him. He negotiated with Algerian nationalist leaders for a cease-fire agreement. The agreement they reached in March 1962 ended more than seven years of bloody war. At de Gaulle’s urging, the French people voted almost 10 to 1 in April 1962 for Algerian independence.

De Gaulle proposed a plan to elect future presidents by direct popular vote. The French Assembly opposed the plan and passed a vote of no confidence in his government in October 1962. But de Gaulle dissolved the Assembly and held a referendum (vote of the people) on direct elections. Voters approved de Gaulle’s proposal and elected a new Assembly that supported the plan.

In 1963, de Gaulle and Chancellor Konrad Adenauer of West Germany signed a treaty providing for political, scientific, cultural, and military cooperation. At the same time, de Gaulle blocked the United Kingdom’s entry into the European Economic Community (EEC), a forerunner of the European Union. In 1964, France became the first Western power to recognize Communist China.

De Gaulle narrowly won a second seven-year term as president in 1965. In 1966, he decided to withdraw French forces from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and to remove NATO headquarters from France. In 1967, de Gaulle again blocked the entry of the British into the EEC. He also created an independent nuclear strike force and criticized U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War (1957-1975).

In 1968, French students and workers staged strikes and demonstrations. The economy suffered from inflation and currency problems, but de Gaulle maintained popular support. In April 1969, however, his new proposals for constitutional changes were defeated in a referendum, and he resigned. De Gaulle died on Nov. 9, 1970, after suffering a heart attack.

See also Algerian War; World War II.