Dinosaur is the name of a group of reptiles that ruled Earth for about 160 million years. These animals died out millions of years ago, but they have fascinated people ever since they were first described in the early 1800’s.

Dinosaurs first appeared on Earth more than 230 million years ago. They then evolved (changed over many generations) into many different forms and spread throughout the world. From about 200 million years ago, almost all large land animals and most small land animals were dinosaurs. They lived in nearly all habitats, from open plains to forests to the edges of swamps, lakes, and oceans.

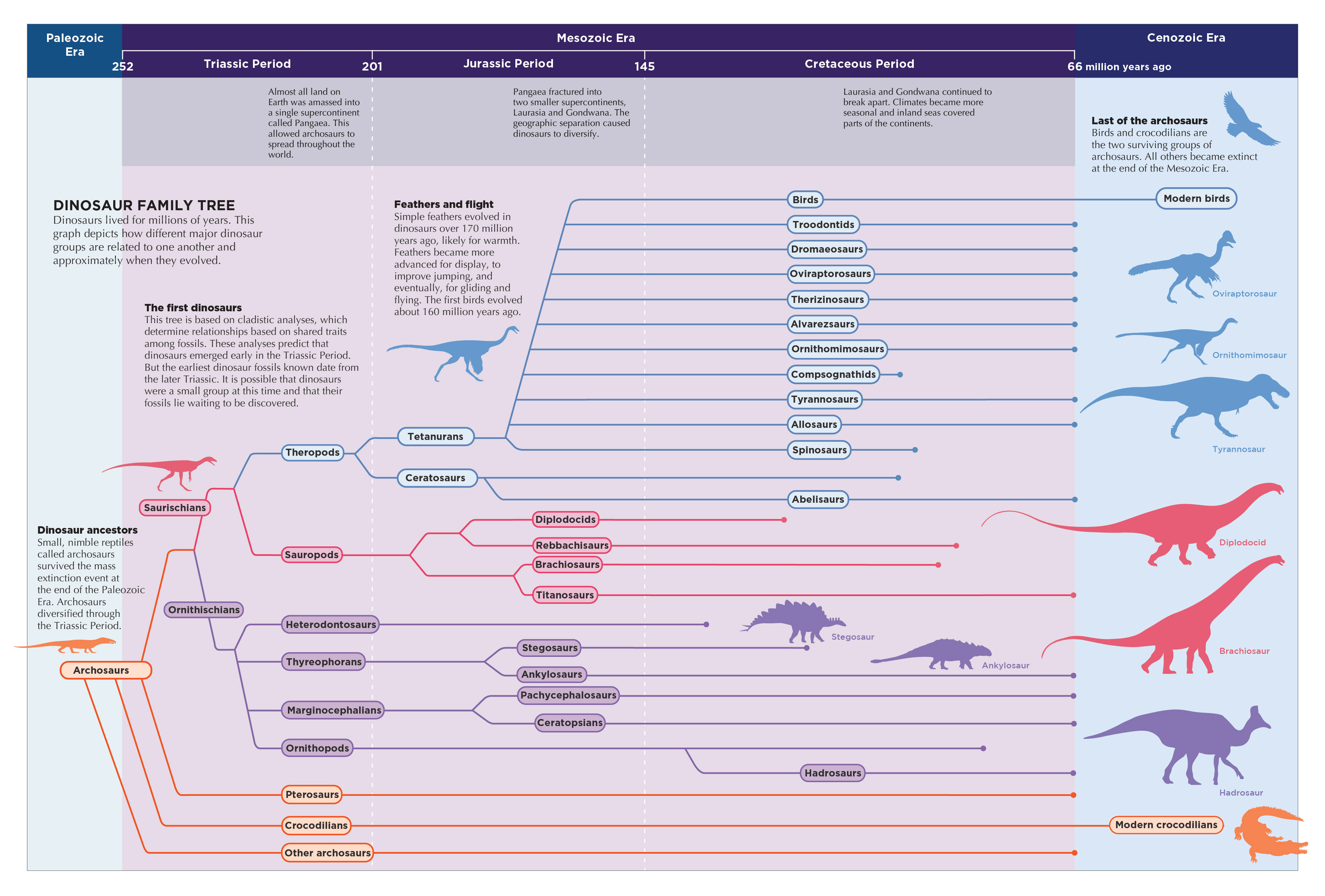

About 66 million years ago, almost all of the dinosaurs became extinct—that is, they had died out. But one group—birds—survived extinction. Scientists have identified several dinosaurs as close relatives of the earliest birds. Many dinosaurs are known to have had feathers. About 9,700 species (kinds) of birds exist today. This article focuses on nonavian dinosaurs (dinosaurs that are not birds), all of which are now extinct. For more information about birds, see Bird.

Dinosaurs came in a fantastic array of shapes and sizes. Many had bony armor, claws, crests, horns, long necks, plates, powerful jaws, sails, and spines. The smallest nonavian dinosaurs were only about 1 foot (30 centimeters) long. But dinosaurs are most famous for the large sizes attained by some species. Some plant-eating dinosaurs were the largest land animals ever to live, reaching over 100 feet (30 meters) long. Likewise, some meat-eating dinosaurs were the largest terrestrial (land-dwelling) predators.

What is a dinosaur?

The name dinosaur comes from the term Dinosauria, which means terribly great lizards. But dinosaurs were not lizards. Like lizards, dinosaurs were reptiles, a group of animals that have dry, scaly skin and breathe through lungs. But they were not very closely related to lizards. Aside from birds, dinosaurs’ closest living relatives are crocodilians, the group containing crocodiles and alligators. The extinct flying reptiles called pterosaurs were even more closely related to dinosaurs.

Similarities with other reptiles.

In certain ways, dinosaurs were like crocodilians. For example, some dinosaurs had teeth much like those of alligators and crocodiles. Many dinosaurs also had scaly skin like that of modern crocodilians. They laid eggs with tough, waterproof shells, just like many modern reptiles do.

Differences from other reptiles.

Dinosaurs were also quite unlike crocodilians and other living reptiles in many ways. For example, no modern reptiles grow as large as the biggest dinosaurs. In addition, many kinds of dinosaurs were bipedal—that is, they walked on their hind legs.

One of the keys to dinosaurs’ bipedal gait and huge sizes was their upright leg posture, which is uncommon among modern reptiles. Lizards, turtles, and most other modern reptiles hold their legs out to the sides of their bodies in a low, sprawling posture. But dinosaurs held their legs under their bodies, much like those of a horse, a dog, or a person. This upright posture enabled dinosaurs to walk without dragging their bellies on the ground.

Paleontologists (scientists who study ancient life) know dinosaurs had an upright posture because of the way the upper leg bone of a dinosaur fit into its hip socket. These bones only fit together in a way that would allow a dinosaur to stand and walk with its legs directly beneath its body. Furthermore, paleontologists have found fossil dinosaur tracks that show the footprints close together. The tracks show no marks between them. Such marks would have been made if the dinosaur’s body or tail dragged along the ground.

Other prehistoric reptiles, such as pterosaurs and marine (ocean-dwelling) reptiles, shared the dinosaurs’ world. But they did not have the special hip structure of dinosaurs. This hip structure is one of the traits paleontologists use to determine whether a fossil skeleton is a dinosaur.

Fossil formation

The world of the dinosaurs

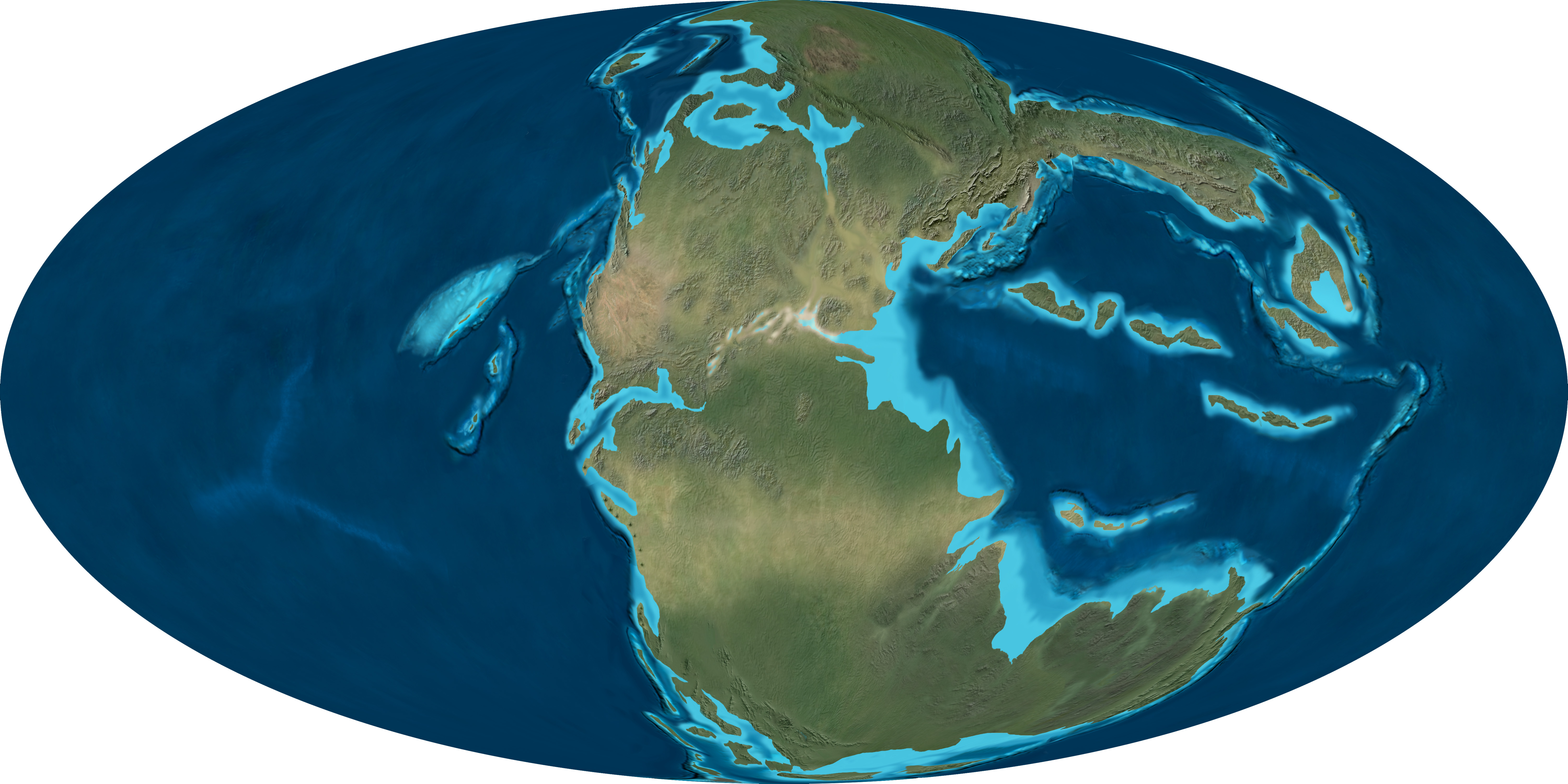

The world in which the dinosaurs lived was quite different than the world is today. Many geographic features we think of as unchanging did not yet exist. Unfamiliar mountain ranges, rivers, and seas covered the landscape. Mammals, which evolved at about the same time as dinosaurs, lived in the shadows. Reptilian sea monsters prowled the oceans. Many plants and animals that are now rare or extinct were common then.

In fact, the world changed drastically during the dinosaurs’ 165-million-year reign. The land on which they lived slowly fractured and drifted apart. Seas covered vast stretches of land and then retreated again. Flowering plants spread throughout the world. Climates became more varied and cooler overall. The environment 66 million years ago would have appeared as strange to the first dinosaurs as it would appear to us.

Geologic time.

Geologists (scientists who study how Earth formed and how it changes) divide the history of Earth into sections of time based on the features within layers of rock. Dinosaurs dominated the planet for most of the Mesozoic Era, a time lasting from about 252 million years ago to about 66 million years ago. Geologists further divide the Mesozoic Era into three periods: (1) the Triassic Period, which lasted from about 252 million years ago to about 201 million years ago; (2) the Jurassic Period, which lasted from about 201 million years ago to about 145 million years ago; and (3) the Cretaceous Period, which lasted from about 145 million years ago to about 66 million years ago.

Land and climate.

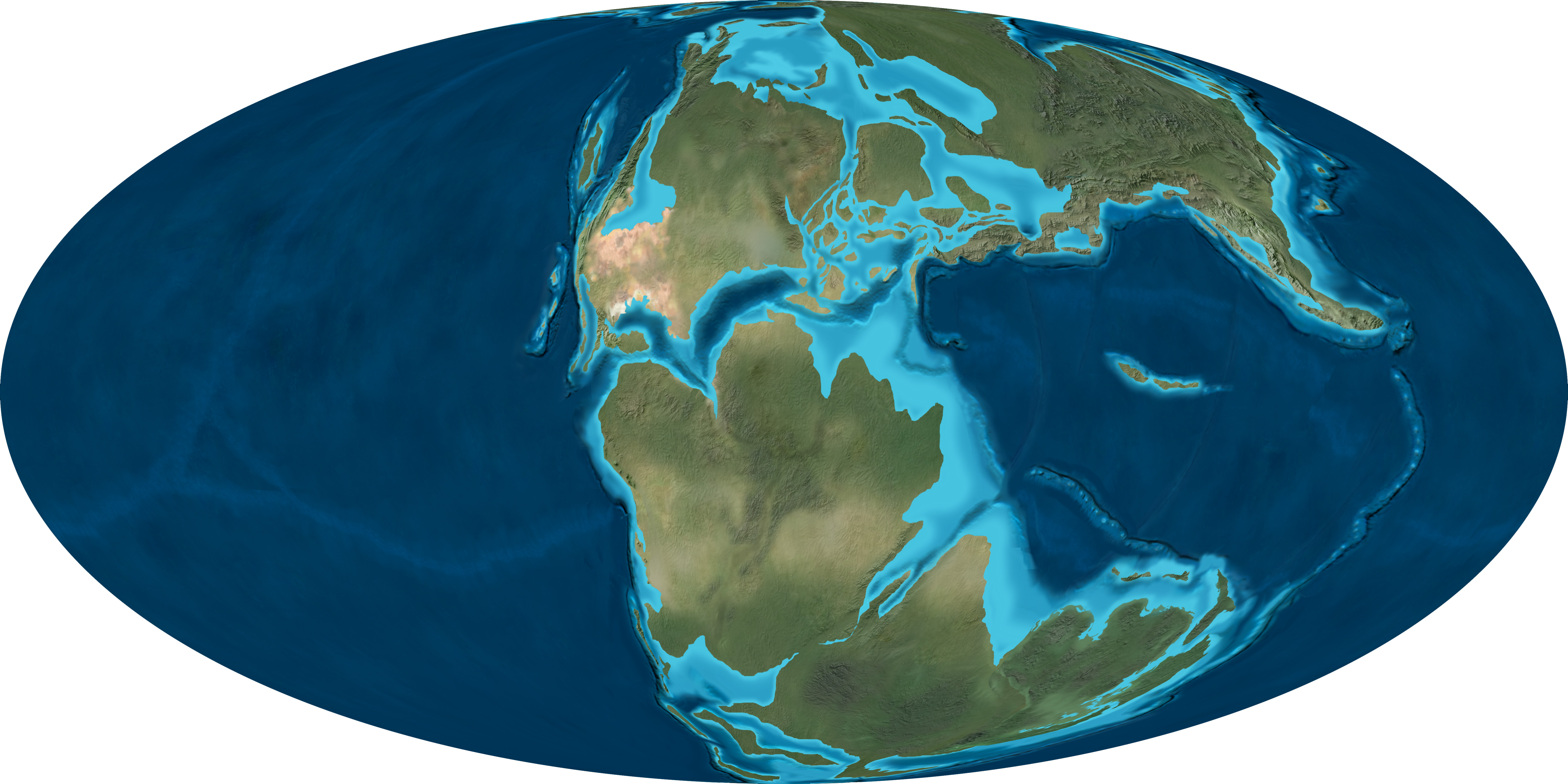

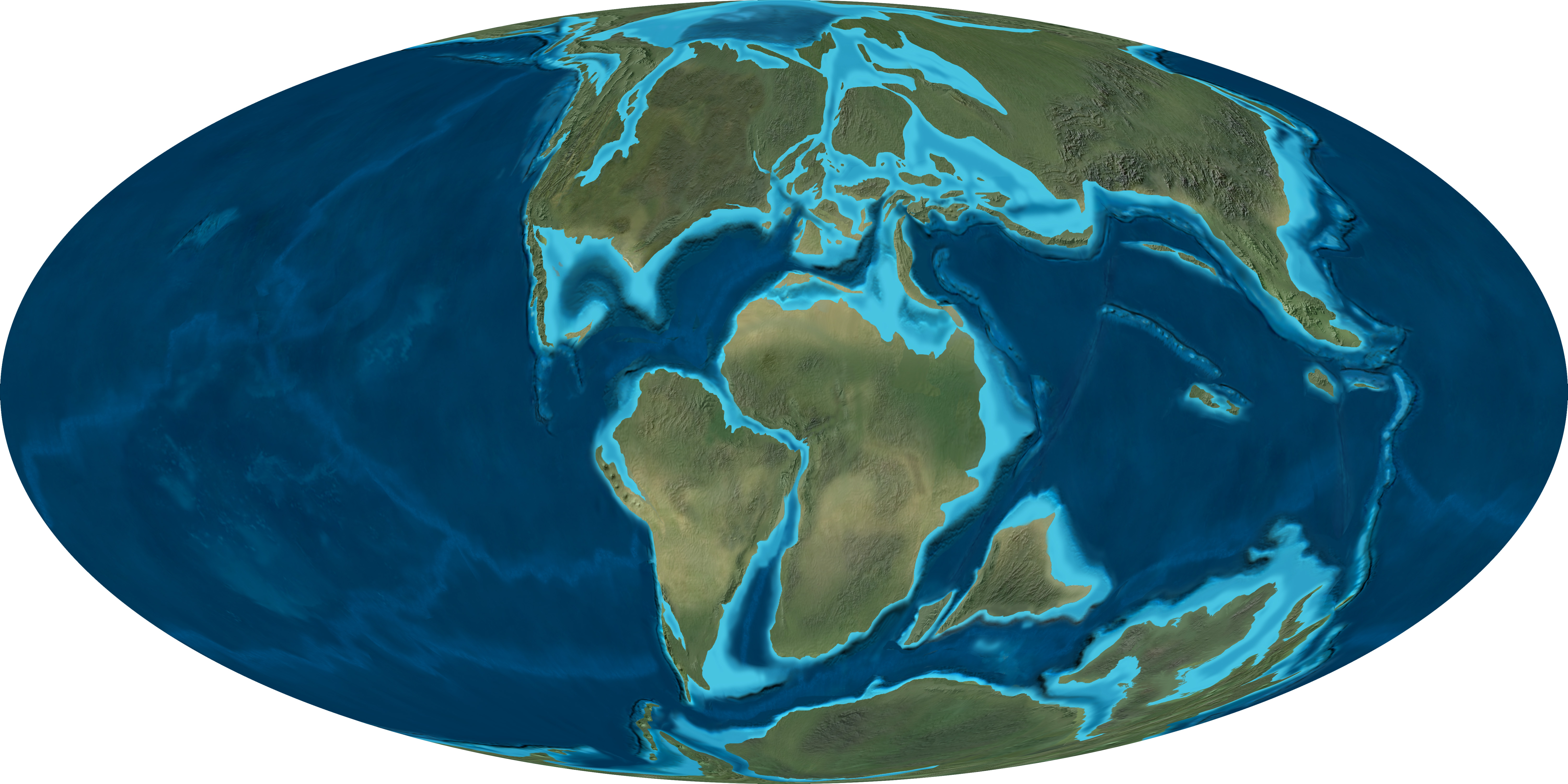

Earth’s continents have not always been arranged as they are today. By the start of the Mesozoic Era, they formed a single huge landmass surrounded by a global ocean. Such a large landmass is called a supercontinent. This supercontinent, which scientists have named Pangaea << pan JEE uh >>, slowly broke apart during the Mesozoic Era. Pangaea first broke into two smaller supercontinents—Laurasia, which consisted of North America, Europe, and most of Asia; and Gondwana, which consisted of the rest of the modern-day continents as well as the Arabian and Indian subcontinents. Throughout the Cretaceous Period, Laurasia and Gondwana fractured further, as the continents drifted toward their present locations.

The breakup of Pangaea directly affected the world’s geographical features and greatly influenced the climate throughout the Mesozoic Era. The colossal mountain ranges at the center of Pangaea eroded. For a time, huge, shallow seas covered portions of North America, Europe, Africa, and Asia. Thick forests bordered drier plains, and swamps and deltas lined the seacoasts. Later in the Cretaceous Period, the seas drained from the continents and the Rocky Mountains began to form.

Throughout the Mesozoic Era, dinosaurs lived in a climate that was milder and less seasonal than the climate today. Areas near the seas and along rivers and lakes may have had mild, moist weather all year round. Inland regions were desert or semidesert. During the Cretaceous Period, the climate grew cooler and drier, and the seasons became more distinct.

Plant life in the Mesozoic

changed substantially throughout the era. During the Triassic and Jurassic periods, forms of conifers (cone-bearing trees), cycads (palmlike trees), and ginkgoes were among the most common plants. Other plant life included ferns, giant horsetails, and mosses. The Cretaceous Period was marked by a broad changeover to flowering plants. Such plants took over many of the ecological niches (roles) previously occupied by other kinds of plants. Forest trees included the first modern conifers as well as early kinds of magnolias, oaks, palms, and willows.

Triassic animals.

A variety of large reptiles lived alongside the dinosaurs during the end of the Triassic Period. Many kinds of crocodilians lived entirely on land, including heavily armored and fast-running forms. Phytosaurs << FY tuh sawrz >> lived and looked much like modern crocodilians, though they were not closely related to them. Aetosaurs << ay EHT uh sawrz >> were tanklike reptiles resembling the later ankylosaur << ANG kuh luh sawr >> dinosaurs. The dominant predators were rauisuchians << `ROW` uh SOO kee uhnz >>, reptiles with tall skulls, powerful jaws, and short limbs. Other large reptiles included piglike dicynodonts << dy SY nuh dahntz >> and rynchosaurs << RIHN kuh sawrz >>. Pterosaurs became the first vertebrates (animals with a backbone) to achieve powered flight. The first mammals and turtles appeared. Other small land animals that lived later in the Triassic included amphibians, insects, and lizards. Ichthyosaurs, marine reptiles that resembled dolphins, lived in the seas.

Jurassic animals.

A mass extinction event at the end of the Triassic Period wiped out many kinds of terrestrial reptiles. Many crocodilians became extinct. Some forms took to the oceans and became medium-sized marine predators. Another kind of marine reptile, called a plesiosaur, also evolved during the Jurassic period. Plesiosaurs had four large flippers and either long necks or gigantic heads. Ichthyosaurs continued to evolve and diversify as well. Birds evolved from small, meat-eating dinosaurs during the Jurassic Period, but they remained small and few in number compared to the pterosaurs. The first snakes and true frogs appeared in the Jurassic Period.

Cretaceous animals.

Birds diversified during the Cretaceous Period. Pterosaurs reached gigantic sizes but declined in diversity. Insects greatly diversified, with such groups as ants and butterflies appearing. Ichthyosaurs died out during the Cretaceous, but lizardlike mosasaurs took their place in the oceans along with the plesiosaurs. Other sea creatures included huge turtles and the first modern bony fish.

Kinds of dinosaurs

Dinosaurs first appeared during the Triassic Period and diversified into several major groups. Most groups were herbivorous (plant-eating), except for a group called theropods << THEHR uh pahdz >>. Paleontologists have discovered the fossil remains of about 1,000 species of dinosaurs. But they estimate that hundreds or thousands more species have yet to be discovered. The following is a selection of major dinosaur groups.

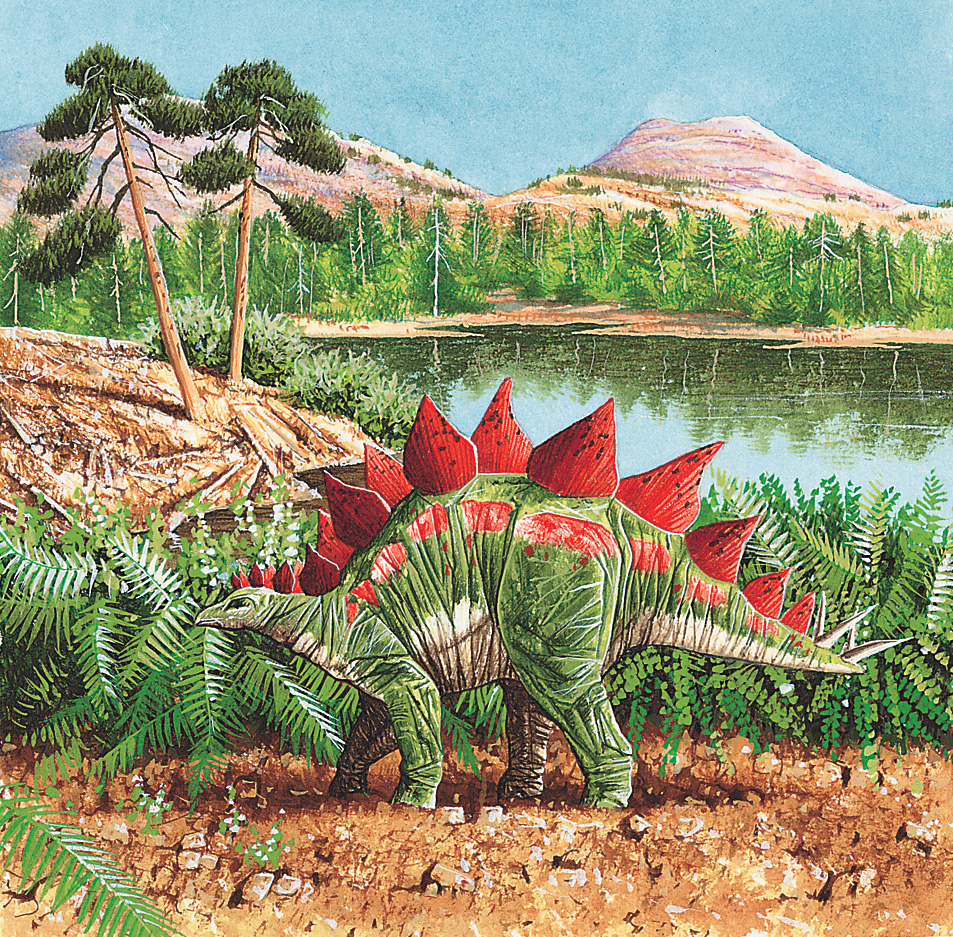

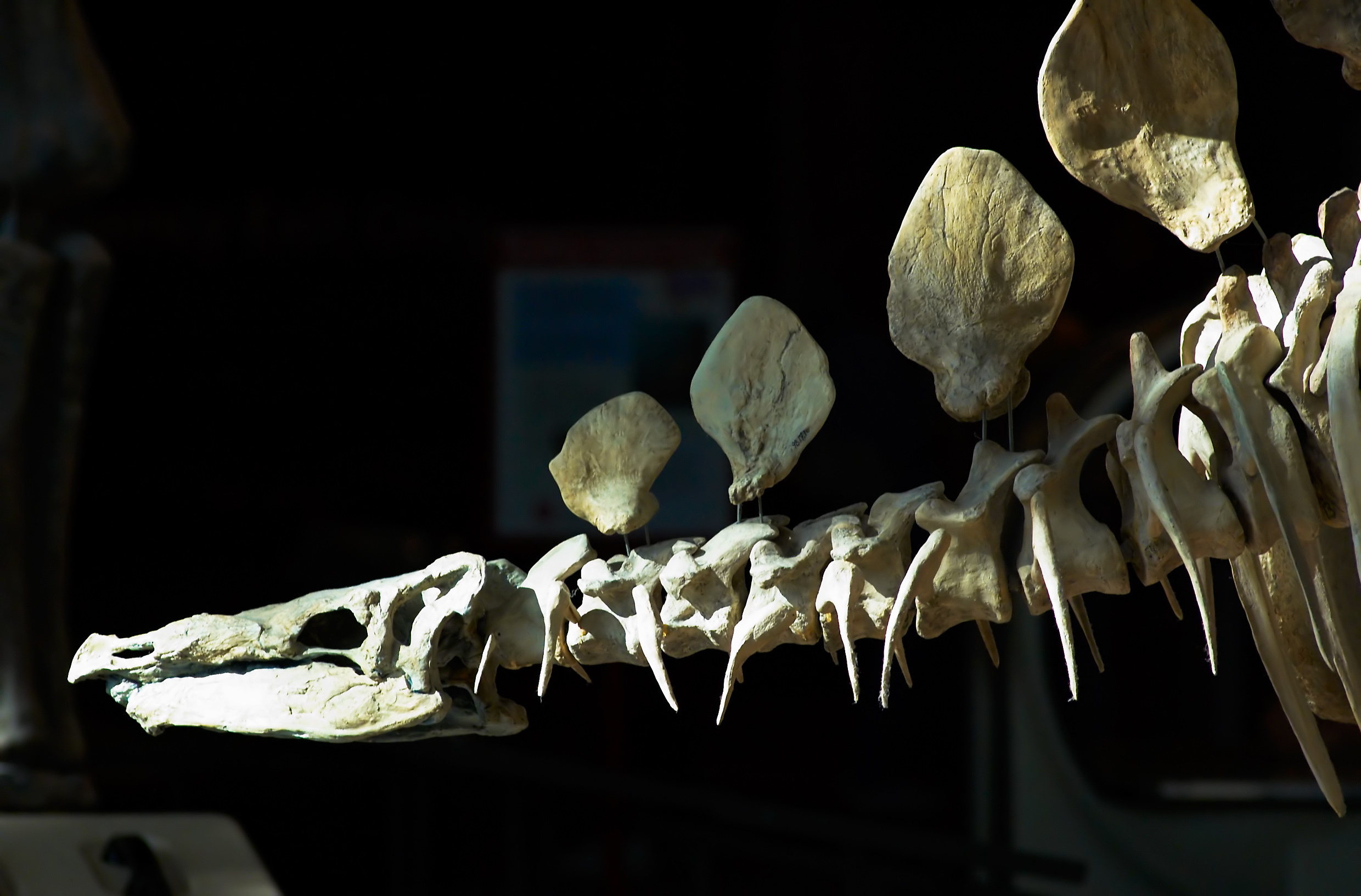

Stegosaurs

were large, plant-eating dinosaurs with huge, upright bony plates or spines along the back. They had a small head and a short neck. Stegosaurs walked on four legs. Stegosaurs’ front legs were much shorter than their back ones. Because of the difference in leg length, stegosaurs walked with their head close to the ground. They lived from the middle of the Jurassic Period to the early part of the Cretaceous Period. They lived in what are now Africa, North America, Europe, and China. Paleontologists have discovered fossils of about 20 species of stegosaurs.

Many kinds of stegosaurs had spikes at the ends of their tails, which they probably used to defend themselves from predators. Their tails were flexible, allowing stegosaurs to swing them at attackers. Paleontologists have discovered a tail bone from the meat-eating dinosaur Allosaurus << `AL` uh SAWR uhs >> with damage that matches the shape of a stegosaur tail spike.

The best-known stegosaur is Stegosaurus, which lived in what is now North America. It was the largest of the stegosaurs, measuring about 30 feet (9 meters) long and about 6 feet (1.8 meters) tall at the hips.

Ankylosaurs

were the most heavily armored of all dinosaurs. They were low, broad animals and walked on four legs. Most kinds of ankylosaurs grew 15 to 30 feet (5 to 9 meters) long and had a skull 2.5 feet (80 centimeters) long. Heavy, bony plates covered the body and head of most ankylosaurs. Many of the plates had ridges or spikes. In some ankylosaurs, large spikes also grew at the shoulders or at the back of the head. Some kinds of ankylosaurs had a large mass of bone at the end of the tail. This bone mass could be swung like a club against attackers.

Ankylosaurs lived in many parts of the world from the middle of the Jurassic Period to the end of the Cretaceous Period. These tanklike animals most frequently ate the leaves of ferns and low-growing flowering plants. Paleontologists have discovered fossils of about 50 species of ankylosaurs.

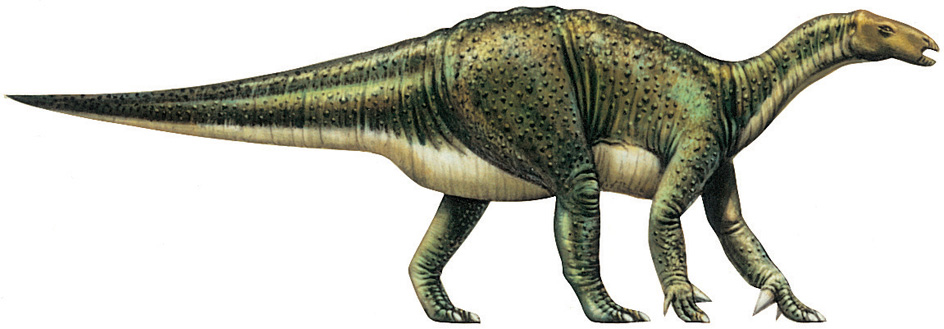

Ornithopods

could walk either on four legs or on their two hind legs. One of the first dinosaur fossil discoveries was that of an ornithopod tooth. This animal, called Iguanodon, measured about 30 feet (9 meters) long. Iguanodon had a bony spike on the thumb of each forelimb. Paleontologists have discovered fossils of over 100 species of ornithopods.

Ornithopods lived throughout the Mesozoic Era. But they reached their greatest diversity with the hadrosaurs << HAD ruh sawrz >>. Hadrosaurs lived at the end of the Cretaceous Period, mostly in what are now Asia and North America. They also inhabited Europe and South America. Hadrosaurs had a broad, ducklike beak of bone at the front of the mouth. This led to the group’s being nicknamed duckbilled dinosaurs, and to early paleontologists’ speculation that they occupied similar environments as ducks do today.

Hadrosaurs had jaws with hundreds of teeth farther back in the mouth, however, which they used to chew tough plant leaves, not soft water plants as ducks do. The snout was tipped with a large, curved beak made of horn. Muscles and cheeks filled in the snout behind the beak, which gave a hadrosaur a smooth snout with a cupped beak, rather than a flat, ducklike bill.

Hadrosaurs had strong hind legs, and they carried their tails stiffly outstretched and parallel to the ground. Although they lacked many of the obvious defensive spines or armor seen in other groups of herbivorous dinosaurs, they could run quickly to escape predators. Some hadrosaurs were 9 feet (2.7 meters) tall at the hips and more than 30 feet (9 meters) long.

Hadrosaurs had a variety of showy head ornamentation. Many had large bony crests containing nasal passages. These structures likely enabled the animals to produce loud, resonant calls. Some specimens of the hadrosaur Edmontosaurus << `EHD` muhn tuh SAWR uhs >> have been preserved with a small, fleshy comb at the top of the head. Depressions in hadrosaur skulls around the nostrils may have held inflatable air sacs. Hadrosaurs likely used these features to communicate and to compete for territory and mates. Well-preserved fossil sites show that hadrosaurs took care of their young, tending the nests and providing the hatchlings with food and protection.

Pachycephalosaurs

were bipedal animals with bony skull ornamentation. They lived in what are now western North America and Asia at the end of the Cretaceous Period. Most measured from 6 to 25 feet (1.8 to 8 meters) long. These dinosaurs had thick domed skulls, often covered with bumps and short spikes. Some paleontologists think that pachycephalosaurs competed for territory or mates in fierce head-butting contests, similar to those seen among modern bighorn sheep and musk oxen. Other scientists think their heads were probably ill-suited to such head-butting matches, since their rounded shapes would have resulted in glancing blows. Instead, they may have battered each other’s flanks. Paleontologists have discovered fossils of about a dozen species of pachycephalosaurs.

Pachycephalosaurs had sharp teeth at the front of the mouth as well as grinding teeth towards the back. Some paleontologists have suggested that they may have supplemented their plant-based diet with meat.

Ceratopsians

are known as horned dinosaurs. Most walked on four feet, resembled rhinoceroses, and ranged in length from about 6 to 25 feet (1.8 to 8 meters). Ceratopsians lived in what are now Asia and North America during the Cretaceous Period. Paleontologists have discovered fossils of more than 70 species of ceratopsians.

Many ceratopsians had an enormous head with a parrotlike beak and a large, bony frill extending across the neck from the back of the skull. One ceratopsian, Pentaceratops << `PEHN` tuh SEHR uh tahps >>, had the largest known head of any land animal. This skull measured about 10 1/2 feet (3.2 meters) long. Most ceratopsians had one horn on the nose and one over each eye. Triceratops had horns over the eyes that grew up to 3 feet (90 centimeters) long. Protoceratops had a small frill and no horns. Psittacosaurus << `SIHT` uh koh SAWR uhs >>, one of the earliest ceratopsians, had neither horns nor frill. It was bipedal and possessed a row of tall bristles running down its spine from the hips to midway down the tail.

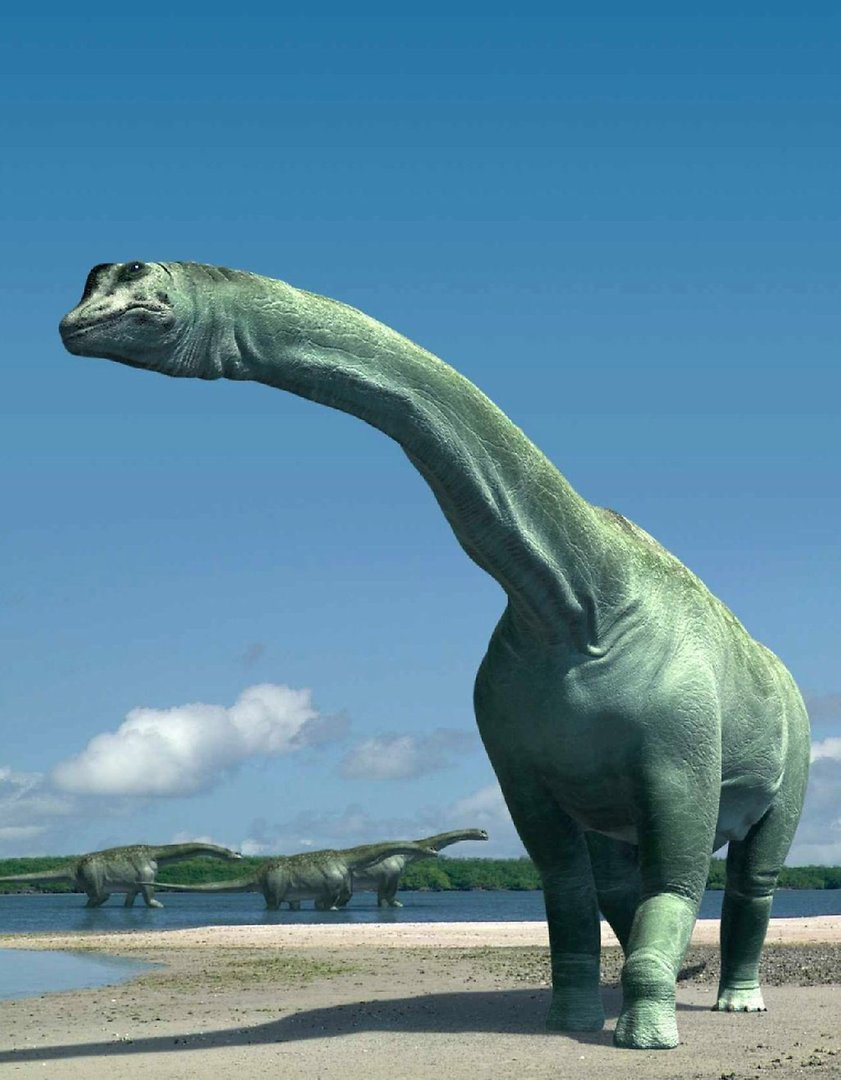

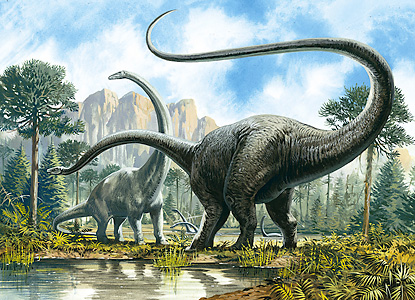

Sauropods

are known for their long necks and tails and huge sizes. These dinosaurs included the largest animals to walk on Earth. Most sauropods were 30 to 60 feet (9 to 18.3 meters) in length. Adults usually weighed from 10 to 30 tons (9 to 27 metric tons). Sauropods were plant-eaters, feeding on the leaves of trees and tall shrubs. Paleontologists have discovered fossils of over 200 species of sauropods.

Early sauropods may have walked on two or four feet, but all later kinds were quadrupedal. These sauropods walked on pillarlike legs, much like those of an elephant. Nearly all sauropods had a long neck, a small head, a long tail, and a huge, deep chest and stomach region.

Sauropods had air sacs connected to their lungs. Projections from these air sacs extended into the interior of certain bones, such as the neck vertebrae, making them lighter. This is likely one of the adaptations that allowed sauropods to reach such large sizes. The huge size of sauropods probably kept them safe from most enemies, but their small offspring had to stay alert to danger. For more information, see Sauropod.

Diplodocids

were one major group of sauropods. The group included such animals as Apatosaurus, Brontosaurus, and Diplodocus. Diplodocids had small, horselike heads and long necks that were likely held close to horizontal. Diplodocids are some of the longest land animals ever to live. The diplodocid Supersaurus measured about 110 feet (33 meters) long. Diplodocids were common in what are now North America, Europe, and Africa during the Jurassic Period.

Brachiosaurs

were a small but well-known group of sauropods. These animals had forelimbs (arm bones) that were taller than their hindlimbs (leg bones), giving them a posture much like a giraffe. They also had high skulls with bony struts. The most famous member of the group is Brachiosaurus. Brachiosaurs lived in what are now Africa, Europe, and North and South America during the Jurassic and the early part of the Cretaceous.

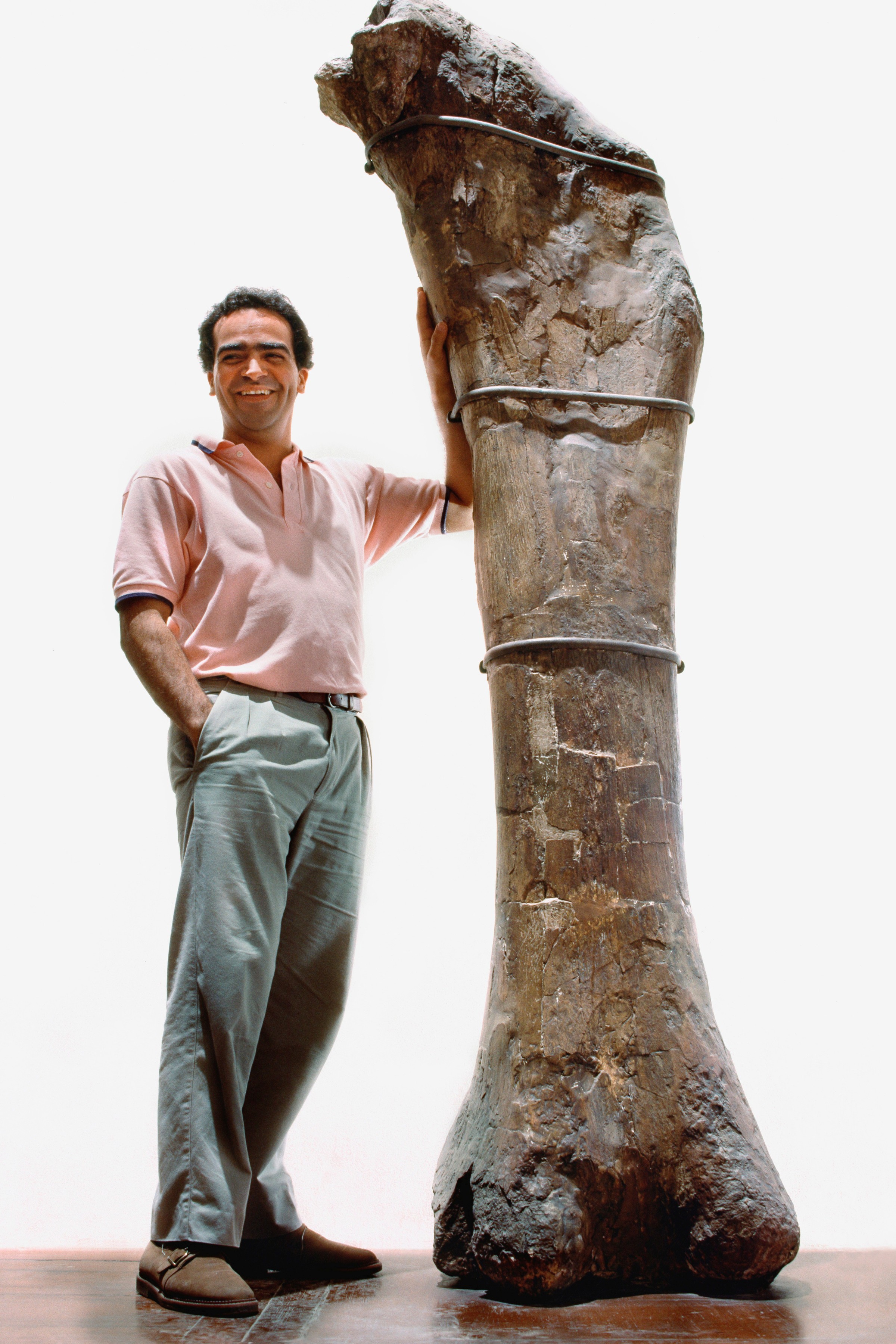

Titanosaurs

represented the last, most successful group of the sauropods. They had broad bodies and necks likely held somewhat upright. The largest titanosaurs were the heaviest land animals of all time. One of these animals, called Patagotitan << puh TAG uh `TY` tuhn >>, is thought to have weighed about 60 tons. Some of the smaller titanosaurs had bony scutes (plates or scales) embedded in their back, probably for protection against predators. Titanosaurs lived throughout the world during the Cretaceous Period.

Theropods

are a diverse group of dinosaurs that includes both birds and the mighty Tyrannosaurus rex. All known theropods, living and extinct, are bipedal. Nearly all nonavian theropods had long, muscular tails, which they carried straight out behind them for balance. Their slender forelimbs ended in grasping hands. Large nonavian theropods usually had short necks and large heads. Small nonavian theropods typically had longer necks and smaller heads. Some nonavian theropods were toothless. Others had the sharp teeth and strong jaws of a predator. Still others were plant-eaters. Most small theropods—and likely some of the larger theropods—had feathers for warmth or display. Paleontologists have discovered fossils of about 500 species of nonavian theropods. For more information, see Theropod.

Abelisaurs

were a group of meat-eating theropods. The more advanced abelisaurs had short snouts and extremely short front limbs. Carnotaurus << kahr nuh TAWR uhs >>, a well-known abelisaur, was about 30 feet (9 meters) long and had thick horns over its eyes. It had long, powerful hind limbs, making it one of the fastest large theropods. Abelisaurs lived in what are now Africa, Europe, and South America during the Cretaceous.

Spinosaurs

were a group of large theropods with long, crocodilelike skulls, powerful arms, and large front claws. They likely hunted fish and other animals from rivers and lakes. Spinosaurus is the largest theropod yet discovered. It grew to about 50 feet (15 meters) long and had a large sail on its back. Scientists are uncertain about the function of this fan-shaped structure, which consisted of skin stretched over spines. Spinosaurs lived in what are now Africa, Europe, and South America during the Cretaceous.

Allosaurs

were a group of large theropods with lightly built skulls full of knifelike teeth. The species Allosaurus was a common predator in the later part of the Jurassic in North America. It grew to about 30 feet (9 meters) in length. Another allosaur, called Giganotosaurus, was among the largest meat-eating dinosaurs. Giganotosaurus lived during the later part of the Cretaceous in what is now South America. It reached 40 feet (12 meters) in length.

Tyrannosaurs

were a famous group of theropods. The largest tyrannosaurs had extremely powerful jaws and thick teeth with serrated (sawlike) edges to deliver crushing bites to large prey. Tyrannosaurs lived in what are now western North America and east-central Asia during the Cretaceous.

The most famous tyrannosaur is Tyrannosaurus rex, which means king of the tyrant lizards. This giant predator stood nearly 12 feet (3.7 meters) tall at the hips and grew to about 40 feet (12 meters) long. Its head measured up to 4.5 feet (1.4 meters) in length, and its teeth were about 6 inches (15 centimeters) long from the base to the tip. The animal had short forelegs with only two fingers, but extremely powerful hind legs. Fossils of another large tyrannosaur named Eutyrannus were discovered showing imprints of simple feathers covering its body. At around 25 feet (7.5 meters) long and weighing more than a ton, it is the largest animal known to have feathers.

Ornithomimosaurs

were theropods with long necks and small heads containing few or no teeth. They probably ate small fruits, the cones of certain trees, and the seeds of flowering plants, as well as eggs, insects, lizards, and small mammals. Medium-sized ornithomimosaurs, such as Ornithomimus, were likely fast runners.

Therizinosaurs

were a strange group of theropods with longer necks, small heads full of weak teeth, and powerful front limbs with long claws. They had a more upright posture than other nonavian theropods. Scientists believe they may have eaten plants or insects. Fossil remains show that at least some therizinosaurs had long, hairlike feathers.

Oviraptorosaurs

were theropods with short, toothless beaks. Some oviraptorosaur fossils have been found near or on top of clutches of eggs. Early paleontologists thought oviraptorosaurs ate such eggs. But the eggs were later found to contain oviraptorosaur embryos. The preserved adults were likely protecting or warming the eggs. The diet of oviraptorosaurs is unknown. They may have used their powerful beaks to break open the shells of marine or aquatic invertebrates.

Dromaeosaurs

were smaller predatory theropods. They are commonly known as raptors. Dromaeosaurs had a large, curved, razor-sharp claw on each of the hind feet, which they used to slash, kill, and cut apart prey. They had feathers on their body and arms. The most famous dromaeosaur is Velociraptor. It grew to about 20 inches (50 centimeters) tall at the hips and 6 feet (1.8 meters) long.

Dinosaur life cycle

Paleontologists have learned enough about dinosaurs to reconstruct some aspects of their life cycle. They study birds, reptiles, and large mammals in addition to fossils to deduce (conclude) how dinosaurs behaved.

Courtship and mating.

Paleontologists think that many prominent features of some dinosaur species resulted from sexual selection. Adults of many species prefer mates who display certain behaviors or have certain external features. Over time, this process can lead to the evolution of complicated courtship rituals, bright coloring to attract mates, and other features. Possible external features of sexual selection in dinosaurs include frills in ceratopsians (which were too thin to provide much protection against predators); crests in hadrosaurs; and feathers among theropods. Paleontologists have also found scrape marks made by the feet of theropod dinosaurs preserved in rock. These marks resemble marks made by modern birds during mating displays.

Like modern birds, dinosaurs are thought to have had an opening called the cloaca at the rear of the body. The cloaca is connected with the digestive system and the reproductive system. Dinosaurs may have mated by pressing their cloacae together, as do birds. Sperm cells passed from the male’s cloaca into the female’s. One or more sperm cells may unite with one or more egg cells in the process of fertilization. Such a union produces a fertilized egg. Glands in the female’s reproductive tract would then secrete a shell around the egg.

Nesting and eggs.

Scientists think that dinosaurs laid eggs with hard or leathery shells. The female may have dug a nest in the soil and deposited eggs in it. Paleontologists have discovered fossil evidence that some groups of dinosaurs, including hadrosaurs and oviraptorosaurs, cared for their eggs and young. Other kinds of dinosaurs, such as sauropods, probably left the young to survive as best they could with little or no parental care.

Growth.

Studies of the microscopic structure of dinosaur bones suggest that dinosaurs grew rapidly. The time it took for a dinosaur to reach adulthood greatly depended on its adult size. The sauropods, for example, may have taken about 25 years to reach their average adult weight of 30 tons (27 metric tons). The smallest dinosaurs, however, likely reached adulthood in a year or less. Most dinosaurs were able to reproduce before they reached their adult size.

Group life.

Fossil evidence shows that many kinds of dinosaurs may have lived in large herds. These dinosaurs included ceratopsians, ornithopods, and sauropods. Gathering in herds would have allowed these dinosaurs to spot predators more easily. They likely used body language, display structures, or sounds to communicate with each other. Other dinosaurs, such as ankylosaurs and tyrannosaurs, may have spent most of their life alone or in small groups.

Getting food.

Most dinosaurs were plant-eaters. They probably fed on a wealth of leaves, small fruits, and seeds from abundant Mesozoic plants. Some sauropods browsed on the leaves of trees and tall shrubs, while hadrosaurs chewed on the foliage of lower branches, shrubs, and ferns. Pachycephalosaurs, ankylosaurs, ceratopsians, and stegosaurs fed on low vegetation growing along the edges of streams and rivers or on open plains.

Many theropod dinosaurs were hunters. They preyed on a wide variety of plant-eating dinosaurs and occasionally, on each other. Some of the small theropods probably ate insects, eggs, mammals, and lizards. The long, narrow jaws of spinosaurs suggest that they ate mainly fish. Most theropods could run quickly to catch their prey. The largest theropods, however, were likely limited to a brisk walking speed. Meat-eating theropods probably scavenged when the opportunity arose, such as finding an animal that had died of other causes, or stealing the kill of a smaller theropod. But little evidence exists for any nonavian dinosaur being a specialized scavenger, such as modern vultures or hyenas.

Life span and death.

Dinosaurs suffered from a variety of parasites and diseases, many of which can be identified in the fossils of older individuals. Such conditions likely weakened most older dinosaurs, preventing them from obtaining food or defending themselves.

Paleontologists can examine the microscopic structure of bones to estimate the age of a dinosaur when it died. Their findings indicate that most dinosaurs likely had a shorter life span than modern reptiles. The maximum life span of theropods was about 3 years for small species and 30 years for large species. Larger dinosaurs likely had a longer life span. Sauropods probably had a life span of as much as 100 years.

Dinosaur origin and evolution

Dinosaurs appeared during the Triassic, a period of Earth’s history that was both preceded and followed by mass extinctions and marked by climatic change. Dinosaurs took advantage of the changing environment and reduced competition to dominate almost all terrestrial habitats and ecological roles.

Before the dinosaurs.

The most severe mass extinction in the history of life on Earth occurred at the beginning of the Triassic Period. It took tens of millions of years for life to recover its previous level of diversity. A group of closely related reptiles called archosaurs << AHR kuh sawrz >>, meaning ruling reptiles, evolved and diversified during this period. Archosaurs included pterosaurs, crocodilians, aetosaurs, and rauisuchians. They all likely possessed an advanced respiratory system that allowed them to be more active than other reptiles.

Dinosaurs appear.

Dinosaurs evolved from archosaur ancestors in the Triassic. Fossils of related groups and footprints indicate that they may have arisen early in the Triassic. But the earliest-known fossils of true dinosaurs date from about 230 million years ago. The first dinosaurs possessed adaptations that allowed them to be fast, nimble predators. But they shared their environment with crocodilian hunters.

A mass extinction event at the end of the Triassic wiped out many reptiles and amphibians, including some rival archosaur groups. Dinosaurs, however, survived this mass extinction. As the sun rose on the Jurassic Period, dinosaurs found a global environment cleared of most competition.

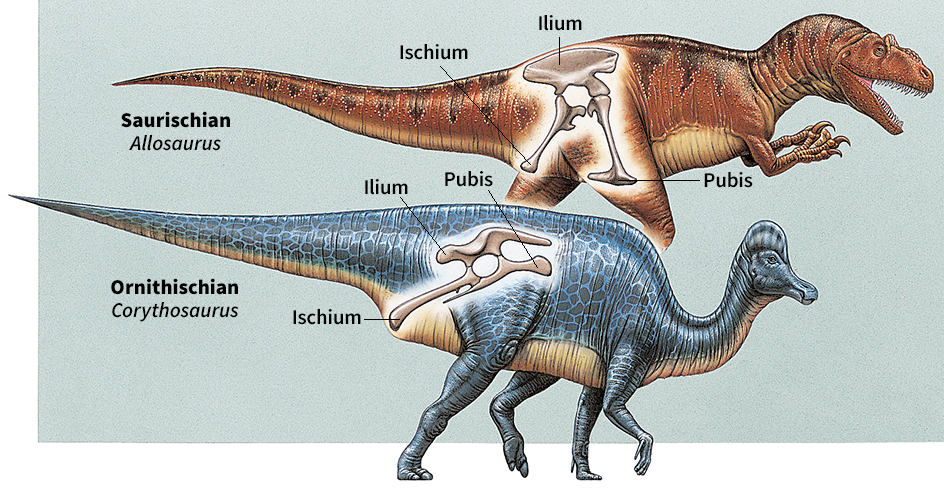

Classification of dinosaurs.

Dinosaurs are usually classified into two groups: (1) ornithischians << `AWR` nuh THIHS kee uhnz >> and (2) saurischians << saw RIHS kee uhnz >>. The two groups differed mostly in the structure of their hips and other skeletal features. Ornithischians, whose name means bird-hipped, had a birdlike hip structure. Ornithischian groups include stegosaurs, ankylosaurs, ornithopods, pachycephalosaurs, and ceratopsians. Saurischians, whose name means lizard-hipped, had a hip structure more like that of lizards. Sauropods and theropods are saurischians.

Surprisingly, birds evolved from saurischians, not ornithischians. Birds and ornithischians developed similar hip features independently.

The base of the dinosaur family tree is not entirely clear. Paleontologists do not agree on the placement of some of the first dinosaurs in the Triassic Period, such as the meat-eating Herrerasaurus << huh `RAIR` uh SAWR uhs >>. Some paleontologists think that theropods and ornithischians are more closely related, while sauropods form a separate group with such dinosaurs as Herrerasaurus.

Extinction of the dinosaurs

For about 160 million years, dinosaurs were the largest and most successful vertebrates on land. Then, about 66 million years ago, they abruptly died out, along with pterosaurs, mosasaurs, and many other reptiles. Mammals thereafter became the world’s dominant land vertebrates. People have been trying to explain why dinosaurs became extinct ever since they were discovered. Today, most scientists think that an impact from an asteroid or comet caused the extinction.

Impact event.

At the end of the Cretaceous Period, an asteroid or comet about 6 miles (10 kilometers) wide collided with Earth. Scientists know a large impact occurred at this time because the layer of rock between the Cretaceous Period and the next geologic period, called the Paleogene, contains large amounts of the chemical element iridium. Iridium is much more common in asteroids and comets than it is in rocks from Earth. This impact created a crater about 125 miles (200 kilometers) across.

The impactor landed in a shallow sea. Today, traces of the impact crater are found in the Gulf of Mexico and on Mexico’s Yucatán << yoo kuh TAN or YOO kuh TAHN >> Peninsula, near the town of Chicxulub << CHEEK shoo loob >>. The impact sent an enormous tsunami (series of ocean waves) crashing into the surrounding coastlines. Molten rock thrown up by the impact crashed back to Earth. The blast of heat from the impact and raining molten rock burned animals and ignited wildfires across the planet.

The dust thrown up by the impact blocked light from the sun. Some studies estimate that the surface air temperature dropped by as much as 47 °F (26 °C) for at least three years after the impact. This dramatic cooling devastated global ecosystems. Most plants died from the darkness and cold. Most animals starved or died of hypothermia (abnormally low body temperature).

The rock thrown up by the impact contained the chemical element sulfur. Over time, sulfur in the dust particles combined with water vapor and came back down to Earth as acid rain. The acidity killed plankton and reef-building organisms, which rely on precise ocean chemistry to build their shells and skeletons. This event devastated ocean ecosystems and led to the extinction of most marine reptiles.

Survivors.

About 75 percent of life on land and about 30 percent of life in the oceans became extinct at the end of the Cretaceous Period. Some mammals and birds survived because they could feed on seeds, nuts, and rotting vegetation. Other survivors may have escaped extinction because they could live at the bottom of lakes or burrow underground. With dinosaurs gone from the environment, mammals diversified and began to fill most habitats during the Paleogene Period.

Other possibilites.

Today, few paleontologists doubt that the impact event at the end of the Cretaceous Period played a part in the extinction of the dinosaurs. Most think it was the major factor in their extinction. But some researchers point to other incidents that may have contributed to the extinction.

Huge volcanic eruptions also occurred at the end of the Cretaceous, in present-day India. These eruptions created huge lava beds called the Deccan Traps. The Deccan Traps cover about 200,000 square miles (500,000 square kilometers). They are more than 1 mile (1.6 kilometers) thick in some places. Such enormous eruptions could have released large volumes of gas, which caused rapid climate change that killed off the dinosaurs.

Some scientists suggest that the dinosaurs were already in decline at the end of the Cretaceous Period, well before the extinction event. They propose dinosaurs were struggling because of competition from mammals or other animals, cooling climates, or fluctuations in sea level. Other paleontologists, however, have found little evidence for such a decline.

History of dinosaur study

Major advances occurred in biology during the 1700’s that enabled the scientific study of dinosaurs. The Swedish naturalist and botanist Carolus Linnaeus devised a systematic method for naming and classifying plants and animals in the mid-1700’s. Two French naturalists, Comte de Buffon and Georges Cuvier, made great advances in the study of fossils and of comparative anatomy. They helped prepare the way for the scientific investigation of the evolution of life on Earth.

Dinosaurs discovered.

Around 1818, an English scholar, William Buckland, received an unusual fossil to examine. The fossil was a jaw from a large prehistoric animal that contained many sharp teeth. After studying this jaw, Buckland concluded that it was unlike any fossil previously discovered. So he gave it a new name, Megalosaurus (great lizard), in 1824.

At nearly the same time, Mary Ann Mantell, an English amateur naturalist, found a large fossilized tooth. Her husband, Gideon, a physician and fossil collector, thought that the tooth came from a huge, iguanalike reptile. Gideon Mantell named this prehistoric creature Iguanodon (iguana tooth) in 1825.

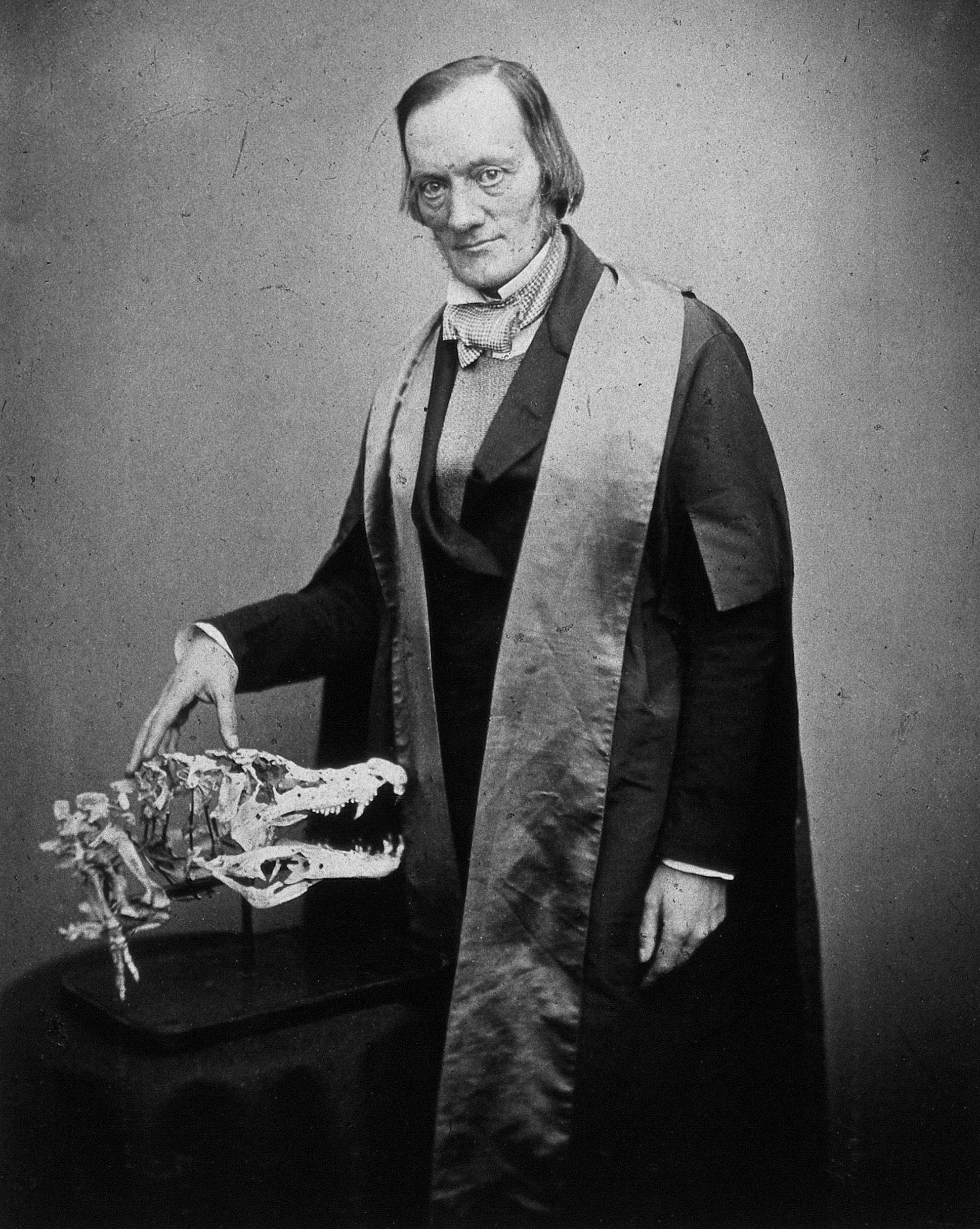

Within a few years, the fossilized remains of several kinds of large, extinct reptiles had been discovered. In 1841, the English scientist Richard Owen suggested that these creatures belonged to a group of reptiles unlike any living animals. In 1842, he called this group Dinosauria. Its members later came to be known as dinosaurs.

Dinosaurs and evolution.

The English scientist Charles Darwin put forth the theory of evolution by natural selection in 1859. Thomas Huxley, an early supporter of Darwin’s theory, proposed a close relationship between dinosaurs and birds. Huxley suspected the two groups shared a common ancestor due to their similar anatomy. Most paleontologists rejected his hypothesis. They argued that the two groups could not be related because birds possess a furcula (wishbone) that dinosaurs appeared to lack. The furcula is a bone formed by the fusion of the two clavicles (collarbones). These scientists thought that birds must have evolved from other reptiles that possessed a furcula. In fact, most dinosaurs do possess a furcula, but scientists overlooked this feature for more than a century.

The Bone Wars.

The American paleontologists Othniel Marsh and Edward Cope discovered dozens of new kinds of dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals from the 1870’s to the 1890’s. They engaged in a bitter competition to find and describe new dinosaur species. This contest is popularly known as the Bone Wars. Although Marsh and Cope’s petty rivalry negatively impacted much of their scientific output, their work did much to popularize dinosaurs. Stories of their discoveries filled newspapers, the fossils they discovered filled museums, and their students continued to unearth new species.

Around this time, however, the value of the term dinosaur for classifying prehistoric reptiles was cast into doubt. In 1888, the British paleontologist Harry Seeley divided dinosaurs into ornithischians and saurischians. He did not think the two groups were closely related. Most other paleontologists accepted his conclusion. Therefore, dinosaur became little more than a popular name for a group of unrelated animals.

Dinosaur doldrums.

By the early 1900’s, scientific interest in dinosaurs had diminished. The American paleontologist Robert Bakker later nicknamed this time the “dinosaur doldrums.” Doldrums means dullness or low spirits. In the 1950’s and 1960’s, however, geologists made a series of discoveries that laid the foundation for a better understanding of the world in which dinosaurs lived. At this time, evidence accumulated to support the theory of plate tectonics—that is, the idea that Earth has an outer shell made up of rigid plates that move. Scientists learned that Earth’s surface was dynamic.

Another advance was the development of radiometric dating techniques to determine the age of fossils. Radiometric methods are based on the fact that certain radioactive isotopes (forms of chemical elements) found in rocks decay at a known rate. Through radiometric dating, paleontologists could determine more precisely when different dinosaurs lived.

The Dinosaur Renaissance.

The 1970’s ushered in a period of renewed interest in dinosaur study that continues to this day. This period is often called the Dinosaur Renaissance. During this time, the scientific view of dinosaurs changed dramatically. Since the first scientific descriptions of dinosaurs in the early 1800’s, most paleontologists had assumed dinosaurs were slow and sluggish beasts, similar to other reptiles. In the late 1960’s, the American paleontologist John Ostrom described a new meat-eating dinosaur that he named Deinonychus. This theropod had a large claw on each foot and a stiffened, muscular tail that acted as a counterbalance while the animal ran and kicked. Ostrom argued that Deinonychus was clearly an active predator, and that perhaps other dinosaurs were active as well.

In the 1970’s, Ostrom studied fossils of early birds and noticed many anatomical similarities with Deinonychus. He suggested that birds descended from small theropod dinosaurs. Ostrom’s student, Robert Bakker, introduced these ideas to the public through articles, television appearances, and his popular book The Dinosaur Heresies (1986).

Before the 1960’s, paleontologists often used observed anatomical similarities to establish relationships between dinosaur groups. However, such relationships were subject to observational biases by researchers. In the 1980’s, paleontologists began using cladistic analysis to determine evolutionary relationships among dinosaurs and other prehistoric life more objectively. In cladistic analysis, researchers carefully evaluate several anatomical traits of similar-looking species. Paleontologists record characteristics as either present or absent while examining multiple specimens. A computer algorithm then determines how these specimens are related to each other. An algorithm is a step-by-step procedure that can be turned into a computer program. These evaluations are used to construct a cladogram, a family tree illustrating how the species are related to one another.

Using cladistic analysis, paleontologists have untangled the large dinosaur family tree. Some of the first cladistic analyses showed that saurischians and ornithischians were, in fact, closely related. Dinosaurs were a natural group after all, as Owen had proposed in 1842.

In 1996, paleontologists discovered fossils of a nonavian dinosaur showing clear evidence of feathers. By this time, many ornithologists (scientists who study birds) and most paleontologists had already accepted the hypothesis Ostrom proposed in the 1970’s—that birds descended from dinosaurs. Paleontologists now think that most theropod dinosaurs had feathered bodies.

The golden age of dinosaur research.

The Dinosaur Renaissance greatly increased public interest in dinosaurs. This interest has led to more funding for paleontology programs, and more young people studying to become paleontologists. Today paleontologists describe a new dinosaur species about every two weeks.

Modern paleontologists also use sophisticated imaging technology to tease more secrets from existing dinosaur fossils. They use computer simulations to learn how dinosaurs moved and how strong they were. Microscopic examination of fossils helps paleontologists determine what dinosaurs ate and even how their bodies were colored. Paleontologists use computed tomography (CT) to examine the interiors of bones and manipulate images of skeletons on computers to aid in dinosaur reconstructions. CT is an X-ray system used to produce images of various parts of the body.

Cultural significance of dinosaurs

Our understanding of dinosaurs has changed dramatically over the years. Scientists once thought these animals were slow-moving, unintelligent creatures that did not adapt well to changing environments. Today, however, scientists believe that dinosaurs were among the most adaptable and diverse animals that ever lived.

Dinosaurs lie at the intersection of popular culture and science. They are safe, scientific monsters. We can wonder at their fantastic, terrifying forms safely separated from them by a huge gap in time. Dinosaurs were long thought of as an evolutionary dead end. The term dinosaur became associated with outdatedness. Through careful study, scientists have learned that dinosaurs were in fact one of the most successful and adaptable groups in the history of life on Earth. Furthermore, dinosaurs rose from the ashes of their extinction to be reborn as the most beautiful of animals—birds.

As popular subjects of books and museum exhibits, dinosaurs are often part of a child’s first exposure to science. Through learning about dinosaurs, children are introduced to such topics as biology, ecology, evolution, geology, physiology, and the concept of deep time.

Appearances in media.

Dinosaurs have been popular culture stars since they were first discovered. In 1853, statues of dinosaurs filled the gardens of the Crystal Palace in London for the World’s Fair. The British author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle depicted fierce dinosaurs surviving in the remote Amazon rain forest in his science-fiction novel The Lost World (1912).

Dinosaurs were among the first—and remain among the most popular—subjects of motion pictures. Gertie the Dinosaur (1914), created by the American animation pioneer Winsor McCay, is a short film about a trained sauropodlike dinosaur. In King Kong (1933), the giant gorilla battles dinosaurs on his home of Skull Island. Early humans lived alongside dinosaurs in the Hanna-Barbera television show “The Flintstones” (1960-1966).

In the 1990’s, dinosaurs were the subject of another breakthrough in animation technology. Jurassic Park (1993) was one of the first movies to make extensive use of computer-generated imagery (CGI). The movie was also among the first to introduce the ideas of the Dinosaur Renaissance to a wide audience.

Controversies.

The popularity of dinosaurs causes difficulties for paleontology. The collection of dinosaur fossils is often poorly regulated. Scientific paleontologists are responsible for only a fraction of the thousands of dinosaur fossils discovered and excavated each year. Many amateur dinosaur fossil hunters work in cooperation with the scientific community. They may donate specimens of high scientific value to museums or collaborate with paleontologists on scientific studies.

However, some people and companies collect dinosaur fossils to sell. Some prospectors may illegally collect fossils, a practice known as “bone rustling.” They may remove a fossil from the surrounding rock without documenting it, thereby destroying much of its scientific value. They may ignore or destroy fossils that appear unimpressive but are actually of great scientific value.

In many countries, dinosaur fossils are considered national property and can only be kept by museums and scientific institutions. However, such laws are often poorly enforced, and a profitable illegal trade in dinosaur fossils exists. In other countries, including the United States, any fossil discovered on private land is considered the property of the landowner. The fossils may be kept or sold. Many paleontologists oppose the private ownership of dinosaur fossils. They may refuse to study privately owned fossils. Some also refuse to study fossils that they believe were collected unethically.