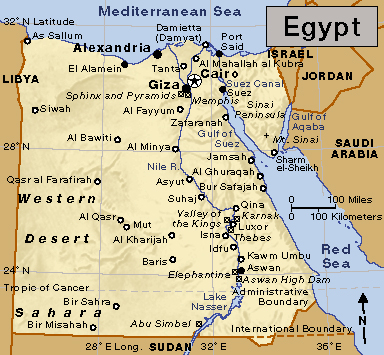

Egypt is a Middle Eastern country in the northeast corner of Africa. A small part of Egypt, the Sinai Peninsula, is in Asia. Little rain falls in Egypt, and dry, windswept desert covers most of the land. But the Nile River flows northward through the desert and serves as a vital source of life for most Egyptians. Almost all of Egypt’s people live near the Nile or along the Suez Canal, the country’s other important waterway.

Egypt is Africa’s third largest country in population. Only Nigeria and Ethiopia have more people. Cairo is Egypt’s capital and largest city.

Egypt’s population has increased tremendously since the mid-1900’s. In addition, many people have moved from rural villages to cities in search of work. As a result, the cities of Egypt overflow with people.

Most Egyptians consider themselves Arabs. More than 90 percent of Egyptians are Muslims. Islam, the Muslim religion, influences family life, social relationships, business activities, and government affairs. Al-Azhar University in Cairo is the world’s leading center of Islamic teaching.

For thousands of years, floodwaters from the Nile deposited rich soil on the riverbanks. As a result, the Nile Valley and Delta region of Egypt contains extraordinarily fertile farmland. Agriculture provides jobs for more than one-fourth of Egypt’s workers. Cotton is one of Egypt’s most valuable crops. Other crops grown in Egypt include corn, fruits, rice, sugar cane, and wheat.

Egypt has expanded a variety of manufacturing industries since the mid-1900’s. Cement, cotton textiles, and processed foods are among the chief manufactured products. Petroleum provides much energy, as does hydroelectric power from the Aswan High Dam on the Nile River.

Egypt is a birthplace of civilization. The ancient Egyptians developed a great culture about 5,000 years ago. They created the first national government, as well as early forms of mathematics and writing. For the story of this civilization, see Egypt, Ancient.

Loading the player...Valley of the Kings in Egypt

Egypt’s hot, dry climate has helped preserve many products of ancient Egyptian culture. Tourists from all over the world travel to Egypt to see such wonders as the Great Sphinx, an enormous stone sculpture with the head of a human being and the body of a lion. They can also marvel at the huge pyramids that the ancient Egyptians built as tombs for their pharaohs (rulers).

Loading the player...Pyramids at Giza

After ancient times, Egypt was ruled by a series of foreign invaders. In 1953, Egypt became an independent republic. Since then, it has played a leading role in the Middle East, especially in Arab affairs. Egypt’s official name is the Arab Republic of Egypt.

Government

Egypt is a republic with a strong national government. A constitution adopted in 1971 declared Egypt a democratic and socialist society. A military government took control of Egypt in 2011 and replaced the 1971 constitution with a temporary charter. The charter was in effect until a new constitution was approved by a referendum (direct vote of the people) in late 2012. The Egyptian army, however, suspended that constitution in July 2013 and installed a new government. In January 2014, Egyptian voters again approved a new constitution.

Egypt's national anthem

National government.

Egypt’s national government has three branches. They are (1) an executive branch headed by a president, (2) a legislative branch to pass laws, and (3) a judicial branch, or court system.

Egyptian voters elect the president. The president appoints a prime minister, who forms a Cabinet of Ministers. In turn, the national government selects all local administrators. Thus, the president has great influence and authority at all levels of government. The president also commands Egypt’s armed forces.

Egypt’s legislature is called the Parliament. It is made up of the House of Representatives, also referred to as the lower house of Parliament, and the Senate, sometimes called the upper house. The House of Representatives consists of 596 seats. The people elect 448 members individually; political parties designate 120 members; and the president appoints 28 additional members. Constitutional amendments that were approved by the people in 2019 restored the Senate. It consists of 300 seats. The people elect 100 senators individually; political parties designate 100 senators; and the president appoints 100 additional senators. Members of both houses serve 5-year terms.

Local government.

Egypt is divided into political units called governorates. A governor appointed by the president heads each governorate. The governorates are divided into districts and villages, which also are run by appointed officials. Elected councils at each level of local government assist the appointed leaders.

Politics.

Egypt’s political environment changed greatly in the 2010’s. The National Democratic Party, which had ruled for decades, was dissolved, and opposition parties were allowed to participate in general elections. The 2014 constitution limited the formation of political parties based on religion, gender, geography, or race. All Egyptian citizens aged 18 or older are required to vote.

Courts.

The Supreme Constitutional Court is the highest court in Egypt. Lower courts include appeals courts, tribunals of first instance (regional courts), and district courts. Under constitutional amendments approved in 2019, the president has the power to appoint the head of the Supreme Constitutional Court and other judicial bodies. There are no juries in Egypt’s court system.

Armed forces.

Egypt maintains a large military, consisting of an army, a navy, an air force, and an air defense command. Men between the ages of 18 and 30 may be drafted for up to three years of military service.

People

About 95 percent of all Egyptians live along the Nile River and the Suez Canal, in an area that covers only about 5 percent of Egypt’s total land. The rest of the country’s people live in the deserts and mountains east and west of the Nile.

Most Egyptians consider themselves Arabs (see Arabs). Bedouins make up a distinct cultural minority among the Arab population. Bedouins are nomads—that is, herders who move about to find pastures for their flock. Most former Bedouins have settled and become farmers, but some nomadic tribes remain in the Egyptian deserts.

The Nubians make up the largest non-Arab minority in Egypt. These people originally lived in villages along the Nile in northern Sudan and the extreme south of Egypt, in a region called the Nubian Valley. Construction of the Aswan High Dam in the 1960’s forced the Nubians to move north along the Nile.

Ancestry.

Since ancient times, numerous groups of people have invaded Egypt and have intermarried with native Egyptians. As a result, present-day Egyptians can trace their ancestry not only to ancient Egyptians, but also to such groups as Arabs, Ethiopians, Persians, and Turks, as well as Greeks, Romans, and other Europeans.

Language.

Arabic is the official language of Egypt. Regional Arabic dialects have different sounds and words. The dialect of Cairo is the most widely spoken dialect throughout Egypt. The Bedouin dialects differ from those spoken by the settled residents of the Nile Valley. People in some desert villages speak Berber rather than Arabic. Many educated Egyptians speak English or French as a second language. See Arabic language.

Way of life

Lifestyles in Egypt’s cities differ greatly from those in its villages. Egyptian city dwellers cope with such typical urban problems as housing shortages and traffic congestion. Although many live in poverty, others enjoy modern conveniences and government services that the cities offer.

Rural life changed greatly during the 1900’s. Many jobs in rural areas are now done with the help of machines. However, much work is still done by hand, and donkeys, water buffaloes, and camels continue to be used for some heavy tasks. For people throughout Egypt, the beliefs and traditions of Islam form a unifying bond.

City life.

Cairo is Egypt’s largest city. The port city of Alexandria is Egypt’s second largest city. Cities in Egypt are overcrowded. Traffic moves slowly, and public transportation is inadequate. Riders crowd onto streetcars and trains.

Great extremes of wealth and poverty characterize Egyptian cities. Attractive residential areas exist beside vast slums. Lack of sufficient housing is a serious problem. Many people crowd into small apartments. Many more build makeshift huts on land that belongs to other people, or on the roofs of apartment buildings. Some of the poorest people in Cairo take refuge in historic tombs on the outskirts of the city, in an area known as the City of the Dead.

The cities provide a variety of jobs. Educated Egyptians work in such professions as business and government. Workers with little or no education find jobs at factories or as unskilled laborers.

Rural life.

Until the 1900’s, the vast majority of Egyptians lived in the countryside. Today, more than half of Egypt’s people still live in rural areas. Almost all of them are peasants called fellahin. They live in villages along the Nile River or the Suez Canal. Most of the fellahin farm small plots of land or tend animals. Many fellahin do not own land. They rent land or work as laborers in the fields of more prosperous landowners. A small minority of Egypt’s rural people are Bedouins who move about the deserts with their herds of camels, goats, and sheep.

The traditional village home used to be a simple hut built of mud bricks with a straw roof. Most huts consisted of one to three rooms, with few furnishings, and a courtyard. Today, many village homes are made of fired bricks or concrete, and they are larger and more comfortable than in the past. Electric power is commonly available, as are televisions, radios, and cassette recorders. Many villages have gained wealth through the earnings of fellahin who have worked outside Egypt, especially in the rich Arab countries of the Persian Gulf. The spread of education and health services has also improved the lives of villagers. However, illiteracy, disease, and poverty remain major problems in rural areas.

Each member of a village family performs certain duties. The husband organizes the planting, weeding, and harvesting of crops. The wife cooks, carries water, and helps in the fields. Children look after the animals and help bring water to the fields.

Egyptian villages are characterized by a strong sense of community. People come together to celebrate feasts, festivals, marriages, and births. Islam, the religion of most Egyptians, provides a strong unifying bond. Mosques (Islamic houses of worship) serve as centers of both religious and social life.

Clothing.

Styles of clothing in Egypt reflect the different ways of life. Many well-to-do city dwellers wear clothing similar to that worn in the United States and Europe. Rural villagers and many poor city dwellers wear traditional clothing. Fellahin men wear pants and a long, full shirtlike garment called a galabiyyah. Women wear long, flowing gowns in dark or bright colors.

Some Egyptians follow Islamic customs in their appearance. Men grow beards and wear long, light-colored gowns and skullcaps. Women wear robes and cover their hair, ears, and arms with a veil.

Food and drink.

Most villagers and poor city dwellers in Egypt eat a simple diet based on bread and ful or fool (broad beans). At a typical evening meal, each person dips bread into a large bowl of hot vegetable stew.

Government-run stores in the cities distribute such food as meat, cheese, and eggs at controlled prices. However, supplies at these stores often run out. The well-to-do city people have more varied diets. They can afford to buy large quantities of meat and imported fruits and vegetables.

Sweetened coffee and tea are favorite beverages throughout Egypt. People also drink the milk of goats, sheep, and water buffaloes.

Recreation.

Soccer is popular in Egypt. Many people attend matches or watch their favorite teams on television. But the main form of recreation in both cities and villages is socializing. People enjoy going to the suq (outdoor marketplace) to make purchases and to visit with friends. They like to sit and talk while drinking cups of coffee or tea, or relax by smoking a kind of water pipe known as a shisha.

Religion.

Islam is the official religion of Egypt. More than 90 percent of the Egyptian people are Muslims—followers of Islam. Almost all of them follow the Sunni branch of Islam. Coptic Christians make up the largest religious minority group in Egypt.

Islam influences many aspects of life in Egypt. Religious duties include praying five times a day, almsgiving (giving money or goods to the poor), fasting, and, if possible, making a pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia, the sacred city of Islam. Muslim traditions also affect government and law. For example, the government collects contributions from the wealthy and gives the money to the poor to fulfill the almsgiving requirement of Islam.

The government officially controls Islam in Egypt, and it appoints major Muslim religious leaders. In villages and city neighborhoods, some Muslims form brotherhoods and hold festivals and ceremonies outside of official control. Some of these groups use force in opposing the government and its religious leaders, whom they view as corrupted by non-Islamic values.

By law, Coptic Christians and other religious minorities may worship freely. But some radical Muslim groups have committed acts of violence against the Coptic community in Cairo and in parts of southern Egypt. See Copts; Islam; Mosque; Muslims.

Education.

About three-fourths of Egypt’s adult population can read and write. Illiteracy is highest in rural areas. The government is working to improve the quality and availability of education.

According to law, all children from ages 6 up to 14 must go to school. But in some places, schools are so crowded that students go for only part of each day to make room for other students. Many teachers provide tutoring services outside school. Education at public elementary and high schools and public colleges is free. Egypt also has many private schools, and a few private universities.

Cairo University is the largest institution of higher learning in Egypt. Al-Azhar University, one of the world’s oldest universities, was founded around A.D. 970. It is a center of Islamic scholarship.

Egypt’s educational system has problems from the elementary through the university level because of overcrowding and lack of funds. There is a shortage of teachers and school buildings, especially in rural areas. Despite these problems, Egypt’s university graduates are among the best trained in the Arab world.

The arts.

Egypt has a rich artistic tradition. Ancient Egyptians created many fine paintings and statues. They also produced and enjoyed music and stories. For more information about the arts of ancient Egypt, see Egypt, Ancient (Painting and sculpture) (Music and literature).

Today, Egypt ranks as a center of the Arab publishing and motion-picture industries. The celebrated works of Egyptian writers and filmmakers have spread Egypt’s culture throughout the Arab world. During the mid-1900’s, the works of such writers as Tawfiq al-Hakim and Taha Hussein realistically described Egyptian and Arab society. In 1988, the Egyptian author Naguib Mahfouz became the first Arabic-language writer to win the Nobel Prize in literature.

Egyptians enjoy traditional and classical music, as well as modern Egyptian and Western music. Egypt’s most popular singer of the 1900’s, Um Kulthum, blended Eastern and Western themes in her songs.

The land

Egypt consists mostly of sparsely settled deserts. But the inhabited areas—along the Nile River and the Suez Canal—are densely populated.

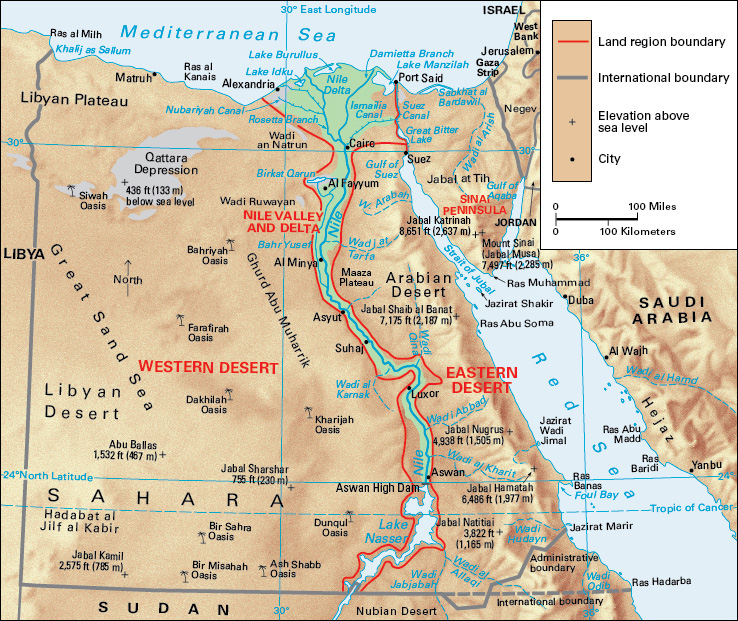

Egypt has four major land regions: (1) the Nile Valley and Delta, (2) the Western Desert, (3) the Eastern Desert, and (4) the Sinai Peninsula.

The Nile Valley and Delta

region extends along the course of the Nile River, which measures about 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) in Egypt. The Nile flows northward into Egypt from Sudan to Cairo. Just north of Cairo, the river splits into two main branches and forms a delta. The Nile River delta measures about 150 miles (240 kilometers) at its base along the Mediterranean Sea, and about 100 miles (160 kilometers) from north to south. See Nile River ; Delta .

The valley and delta region contains most of Egypt’s farmland. Without the precious waters of the Nile, Egypt would be little more than a desert wasteland. For thousands of years, annual floods of the Nile deposited valuable soils upon the narrow plain on either side of the river and upon the low-lying delta. Almost all of Egypt’s people live in the valley and delta region. Many of them farm its fertile soil.

In the southern part of the valley, the Aswan High Dam provides water for irrigation of the lands along the Nile. It also prevents severe damage from the Nile’s annual flooding. Lake Nasser, a huge lake created behind the dam, catches and stores the floodwaters. The Aswan High Dam allows Egyptians to cultivate usable farmland more thoroughly. But the dam also collects a great deal of valuable soil. As a result, this soil is no longer deposited on the farmland that borders the Nile. See Aswan High Dam; Lake Nasser

The Western Desert,

also called the Libyan Desert, is part of the huge Sahara that stretches across northern Africa. It covers about two-thirds of Egypt’s total area. The Western Desert consists almost entirely of a large, sandy plateau with some ridges and basins, and pit-shaped areas called depressions. The Qattara Depression, Egypt’s lowest point, drops 436 feet (133 meters) below sea level. It contains salty marshes, lakes, and badlands (regions of small, steep hills and deep gullies). Small villages occupy scattered oases in the desert.

The Eastern Desert,

or Arabian Desert, is also part of the Sahara. The desert rises eastward from the Nile as a sloping, sandy plateau for about 50 to 80 miles (80 to 130 kilometers). It then turns into a series of rocky hills and deep valleys called wadis. The land in this region is virtually impossible to cultivate. As a result, the Eastern Desert is mostly uninhabited, except for a few villages on the coast of the Red Sea.

The Sinai Peninsula

is a desert area that lies east of the Suez Canal and the Gulf of Suez. It consists of a flat, sandy coastal plain in the north, a high limestone plateau in the central area, and mountains in the south. Egypt’s highest point, Jabal Katrinah, rises 8,651 feet (2,637 meters) above sea level in the southern Sinai. Though desolate, the Sinai Peninsula has valuable oil deposits. About 600,000 people live on the peninsula.

Climate

Egypt has a hot, dry climate with only two seasons—scorching summers and mild winters. Summer lasts from around May to October, and winter lasts from around November to April. January temperatures range from an average high of 65 °F (18 °C) in Cairo to an average high of 74 °F (23 °C) in Aswan. July temperatures reach an average high of 96 °F (36 °C) in Cairo, and 106 °F (41 °C) in Aswan. Daily temperatures in the deserts vary greatly. The average daytime high temperature is 104 °F (40 °C), while the temperature may drop to 45 °F (7 °C) after sunset. North winds from the Mediterranean Sea cool the coast of Egypt during the summer, so many wealthy Egyptians spend the hot summer months of July and August in Alexandria.

Most of Egypt receives little rain. Winter rainstorms occasionally strike the Mediterranean coast, where about 8 inches (20 centimeters) of rain fall each year. Inland, rainfall decreases. Annual rainfall in Cairo averages about 1 inch (2.5 centimeters). Southern Egypt receives only a trace of rain each year.

Around the month of April, a hot windstorm called the khamsin sweeps through Egypt. Its driving winds blow large amounts of sand and dust at high speeds. The khamsin may raise temperatures as much as 68 Fahrenheit degrees (38 Celsius degrees) in two hours, and it can damage crops.

Economy

Egypt is a developing country with a number of economic problems. For example, Egypt must import much of its food supply to feed its increasing population. At the same time, its petroleum exports have been reduced because of increased demand within the country. Thus, Egypt faces a foreign debt, as the cost of its imports far exceeds its income from exports.

During the 1950’s and 1960’s, the government of Egypt took over almost all large-scale business and industry. Farms and small businesses remained privately owned. Today, government ownership continues to dominate in most major industries. However, the government has tried to encourage more private investment in the production of goods and services.

Service industries

are economic activities that provide services rather than produce goods. Such industries have become increasingly important to the Egyptian economy. Today, service industries account for about half of both Egypt’s gross domestic product (GDP) and its employment. The GDP is the total value of all goods and services produced within a country in a year.

Trade, restaurants, and hotels is the leading service industry group in terms of GDP. This group benefits from the millions of tourists who visit Egypt each year. Many tourists come from Germany, Italy, Russia, and the United Kingdom. The community, government, and personal services group employs about one fourth of Egypt’s workers.

Manufacturing

has expanded rapidly in Egypt since the 1950’s, when the government took a leading role in promoting industrialization. Egypt has privatized some of the manufacturing industry, returning it to private ownership. However, the government still controls much of the country’s manufacturing.

Food processing and textile production are among the most important industries. Egypt also manufactures cement, chemicals, motor vehicles, and steel. Oil refineries operate in Alexandria, Cairo, Suez, and other cities. Alexandria and Cairo are the leading manufacturing centers.

Agriculture

accounts for only about 11 percent of Egypt’s GDP, but it employs about 25 percent of the country’s workers. Almost all of Egypt’s farmland is along the Nile River. Nearly all farmland is privately owned. Many of Egypt’s farms are 1 acre (0.4 hectare) or less.

For centuries, Egyptian farmers relied on the annual floods of the Nile River to irrigate their fields and renew the topsoil. Each year, before the Nile flooded in July and August, farmers created a series of basins on surrounding farmland. When the Nile overflowed, these basins trapped the floodwaters and the silt (tiny particles of soil) that they carried. After the floodwaters withdrew, farmers planted their fields.

Beginning in the 1800’s, Egyptians replaced the basin irrigation system with a system of year-round irrigation. They built dams, canals, and reservoirs to capture Nile water and make it available throughout the year. The changeover was completed with the building of the Aswan High Dam, which began operation in 1968. The dam has increased the amount of land irrigated all year by about 2 million acres (800,000 hectares). Today, nearly all of Egypt’s farmland has continuous irrigation. As a result, farmers can plant crops the year around.

Cotton is one of Egypt’s most valuable crops. Egypt produces much of the high-quality long-staple (long-fibered) cotton. Such cotton is known for its strength and durability. Other important crops include corn, onions, potatoes, rice, sugar beets, sugar cane, tomatoes, wheat, and fruits, such as apples, bananas, grapes, oranges and other citrus fruits, and watermelons. Egypt leads the world in the production of dates, which are grown mainly in the desert oases. Egypt is also a leading producer of eggplants and figs.

Goats and sheep are raised for meat, milk, and wool. Cattle and water buffaloes, kept chiefly as work animals, also provide meat and milk. A large number of farmers raise chickens for meat and eggs. Some camels, ducks, and geese are also raised.

Mining.

Egypt’s most important minerals are petroleum and natural gas. Oil is found in the Eastern and Western deserts, in the Nile Delta, on the Sinai Peninsula, and offshore in the Gulf of Suez and the Mediterranean Sea. Natural gas is plentiful in the Nile Delta, in the Western Desert, and offshore in the Mediterranean Sea. Egypt also mines gold, gypsum, iron ore, manganese, and phosphate rock.

Tourism.

Egypt’s warm, dry climate and its beautiful relics from ancient times attract visitors from all over the world. Large numbers of people travel to Egypt each year to admire such wonders as the giant pyramids and the Great Sphinx at Giza. Near Luxor, ancient tombs in the Valley of the Kings and magnificent temples draw many tourists. Visitors to the city of Cairo admire its beautiful mosques, city walls and gates, and traditional Islamic architecture. Egypt’s Red Sea resorts are attracting growing numbers of visitors, who come to enjoy the sunny beaches and spectacular coral reefs. But since the 1990’s, Egypt’s tourism industry has suffered greatly because of visitors’ fears of terrorism. See Pyramids; Sphinx; Valley of the Kings. Loading the player...

Great Sphinx

Energy sources.

Natural gas and petroleum provide most of Egypt’s energy. The hydroelectric plant of the Aswan High Dam generates a large amount of low-cost electric power (see Aswan High Dam).

International trade.

Egypt imports more goods than it exports. Imports include machinery; petroleum products; transportation equipment; and food products, such as corn and wheat. Egyptian exports include clothing; crude oil and petroleum products; fertilizer; gold; iron and steel; and food products, such as fruits, rice, and vegetables. Leading trade partners include China, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Turkey, and the United States.

Transportation and communication.

For thousands of years, the Nile River was the primary means of transportation within Egypt. Today, transportation takes many forms. Roads and railroads connect all important cities and towns. Two main highways link Alexandria and Cairo. One highway stretches across the desert and the other passes through the densely populated Nile Delta.

Cairo has Egypt’s busiest international airport. Alexandria, Hurghada, Luxor, and Sharm el-Sheikh (also spelled Sharm ash Shaykh) on the Sinai Peninsula also have international airports. Egypt’s government-run airline, EgyptAir, provides service throughout the country and to and from foreign cities. Alexandria, on the Mediterranean Sea, ranks as Egypt’s leading port. Two other major ports, Port Said and Suez, lie on the Suez Canal. The Suez Canal is one of the busiest interoceanic waterways in the world. An interoceanic waterway is one that lies between two oceans.

Cairo serves as the center of Egypt’s communications industries. Egypt’s leading daily newspapers include Al-Ahram, Al-Akhbar, and Al-Jumhuriyah. The Egyptian government owns and controls the nation’s main radio and television stations. Many Egyptians can also access international or privately-owned satellite broadcasting. Internet and cell phone usage have increased since the early 2000’s.

History

Egypt’s long, colorful history goes back more than 5,000 years to about 3100 B.C. For the story of Egypt until it was conquered by Muslim Arab armies between A.D. 639 and 642, see Egypt, Ancient (History).

Muslim rule.

In A.D. 639, Arab Muslims, inspired by the birth of Islam, burst out of Arabia and invaded Egypt. At the time, Egypt was a province of the Byzantine, or East Roman, Empire. The Arabs captured Alexandria, which was then the capital of Egypt, in 642. Their commander, Amr ibn al-As, established a military camp and settlement in what is now part of Cairo. The Arab conquest transformed Egypt. The Egyptian people gradually adopted the Arabic language, and many converted from the Coptic Christian religion to Islam. See Muslims.

Egypt became an important province of the Islamic Empire, which was ruled by Arab Muslim leaders called caliphs. Caliphs of the Umayyad dynasty (family of rulers) governed Egypt from Damascus (now the capital of Syria). They were followed by the Abbasid dynasty, which ruled from Baghdad (now the capital of Iraq).

In the mid-800’s, the Abbasids began to lose control over their territories. For most of the period between 868 and 969, two Turkish dynasties—the Tulunid dynasty and the Ikhshidid dynasty—ruled Egypt almost independently of the Abbasid caliphs in Baghdad.

In 969, Fātimid rulers seized Egypt. The Fātimids, who had conquered other lands in northern Africa, made Egypt the center of their expanding empire and broke its ties with the Abbasid state. The Fātimids claimed to be descendants of Fātimah, daughter of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. They were members of an Islamic minority group known as Shī`ites. The Fātimids founded the city of Al-Qahirah (modern-day Cairo), and they made it their capital in 973. They also built al-Azhar mosque, which quickly became the center of Fātimid culture and religion. See Fātimid dynasty.

By the mid-1100’s, the Fātimid empire was weakened by fighting among various factions and with the Christian Crusaders from Europe (see Crusades). In 1168, the Fātimid caliph asked Muslims in Syria to send an army to help defend Egypt from the Crusaders. Saladin, an officer in that army, helped drive the Crusaders out of Egypt. Then in 1171, he overthrew the Fātimid ruler, restored the Sunni form of Islam—that is, the form most Muslims follow—and created an independent state. He became the sultan (prince) of Egypt. Saladin was a generous and just ruler. He and his descendants formed the Ayyubid dynasty, which ruled Egypt until 1250.

A group known as the Mamluks served as the sultan’s bodyguard. They were Turkish, Mongol, and Circassian enslaved people who were given special military training and rose to high positions in the army and government. In 1250, the Mamluks revolted against the Ayyubid sultan and seized control of Egypt. The Mamluk general Baybars, who later became sultan, saved Egypt from ruin when his forces defeated invading Mongol troops at the battle of Ayn Jalud in Palestine in 1260.

For more than 200 years, rival Mamluk groups competed for authority, with the largest, best-organized, and most ruthless group taking power. But Egypt achieved more in art, architecture, and literature under the Mamluk rulers than at any time since the beginning of the Islamic period. See Mamluks.

Ottoman and French control.

The Mamluk empire was declining by 1517. That year, Ottoman forces under Sultan Selim invaded Egypt from Syria and overthrew the Mamluks. But the Ottomans could not eliminate Mamluk influence. Mamluks became beys (governors) of the regions of Egypt and held the real governing power. By the mid-1700’s, Egypt’s government was in disarray as Ottoman and Mamluk leaders competed for power. At the same time, the economy suffered from European control of Indian Ocean trade routes that bypassed Egypt.

In 1798, Napoleon Bonaparte led French forces into Egypt. They defeated the Mamluks in the Battle of the Pyramids (see Napoleon I (Egypt invaded)). Napoleon hoped to disrupt the trade routes of Britain (now the United Kingdom), France’s chief enemy. He also wanted to establish a French colony in Egypt. Napoleon brought many French scholars with him to Egypt. Their scientific investigations helped revive the study of Egyptian relics, and their writings provided thorough descriptions of the country at the end of the 1700’s.

Napoleon returned to France in 1799, leaving his troops behind. But military defeat, Egyptian resistance, and disease weakened them. The Ottomans, with British assistance, forced the French to withdraw in 1801.

Muhammad Ali and modernization.

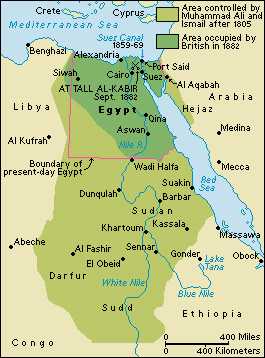

Muhammad Ali was an officer in the Ottoman army that helped drive the French out of Egypt in 1801. In the disorder following the departure of the French, he gained power rapidly. By 1805, Muhammad Ali had established himself as Egypt’s ruler. His killing of Mamluk rivals in 1811 made his rule secure from rebellion. From then on, he carried out a program of modernization.

Muhammad Ali was an energetic leader who ruled with absolute power. Many of his reforms came from a desire to strengthen Egypt’s army. Muhammad Ali knew that his position in Egypt remained secure only as long as his army was more powerful than that of the Ottoman sultan. To achieve this goal, he brought in French military experts and patterned his army on that of France. In addition, Muhammad Ali introduced Western education into Egypt. He sent educational missions to Europe and brought European teachers to Egypt. Muhammad Ali also worked to improve agriculture. He began the transformation from basin irrigation to year-round irrigation. He also promoted the industrialization of Egypt.

Many of Muhammad Ali’s reforms failed, partly because he tried to do too much too fast. His projects overtaxed the country’s resources and caused hardship to much of the population. He also aroused the hostility of the United Kingdom by invading Syria and threatening the existence of the Ottoman Empire, thus upsetting the balance of power in the Middle East. In 1841, the British forced Muhammad Ali to accept a decree that limited his army to 18,000 men. At the time of his death in 1849, Muhammad Ali’s industries had collapsed, his educational missions had been disbanded, and many schools had been closed. See Muhammad Ali.

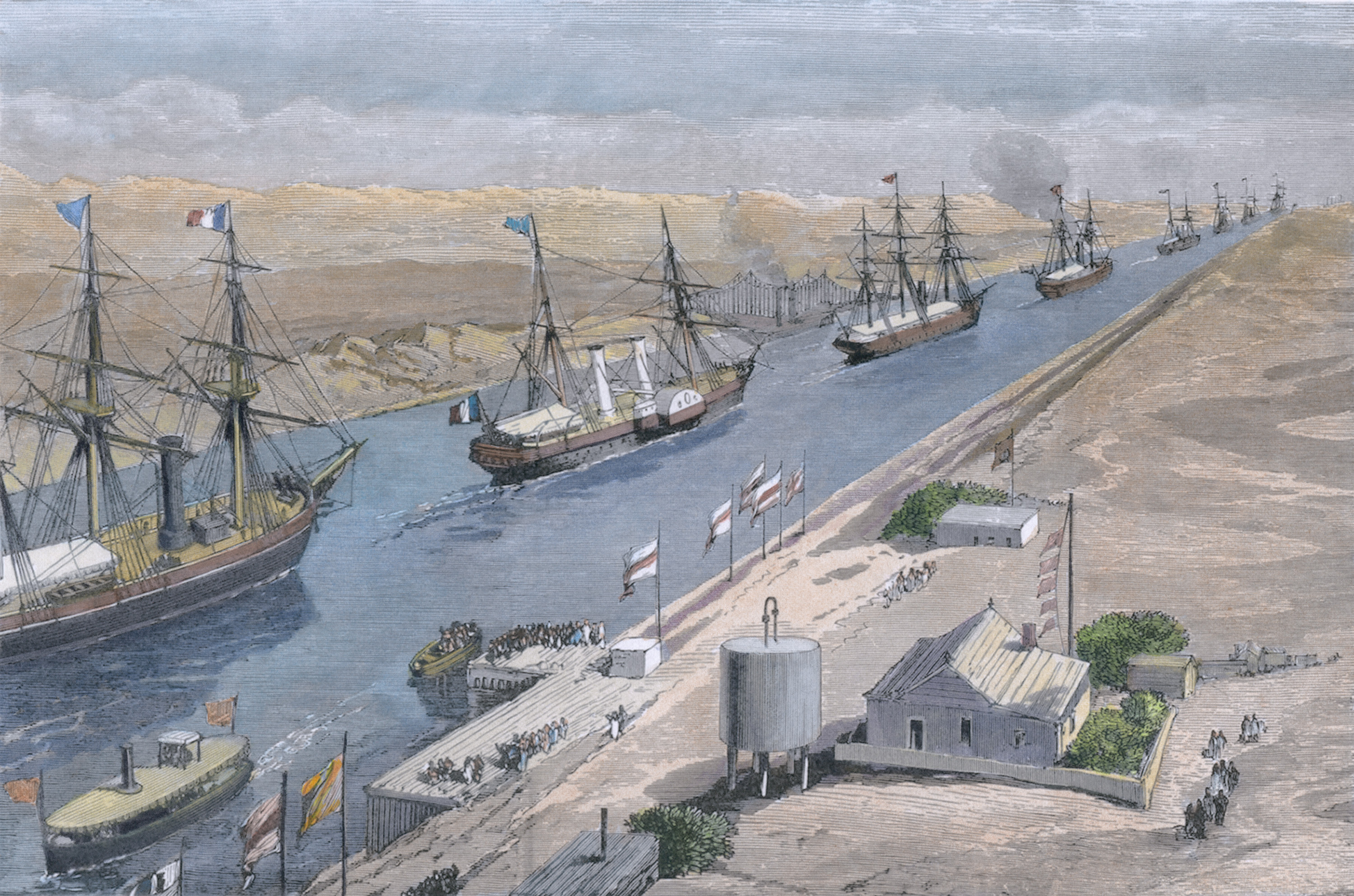

Muhammad Ali’s immediate successors did not provide strong leadership. His son Said, also called Said Pasha, ruled from 1854 to 1863. Said granted a French company a contract to build a canal through the Isthmus of Suez. The canal was designed to shorten the sailing route between Europe and eastern Asia by linking the Red Sea and the Mediterranean Sea. Construction of the Suez Canal began in 1859, and the canal opened in 1869.

Ismail, Said’s nephew, ruled Egypt from 1863 to 1879 and became the khedive (ruler). Ismail successfully expanded the educational system; built many roads, canals, and railroads; and increased the export of cotton. But he spent large amounts of money on palaces, boulevards, and public displays. By the 1870’s, Ismail’s lavish spending had created a large national debt. To help pay off the debt, Ismail sold Egypt’s shares of ownership in the increasingly profitable Suez Canal Company to the British government in 1875. As a result, the United Kingdom became the largest shareholder in the canal. See Suez Canal.

British control.

During the 1800’s, the United Kingdom’s interests in Egypt steadily increased. When Ismail tried to combat European influence in Egypt, the British helped bring about his removal in favor of his son Tawfiq. In 1881 and 1882, Egyptian army officers led by Colonel Ahmad Urabi staged uprisings in an attempt to establish a more independent and nationalist regime in Egypt. Fears that Urabi’s actions would endanger foreign interests eventually led the British to invade Egypt. In September 1882, British forces defeated the Egyptian army at the battle of Tel al-Kabir and marched into Cairo. The British exiled Urabi and returned Tawfiq to power.

During the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, the khedive ruled Egypt in name only. A series of powerful British administrators actually directed the country’s affairs. They improved some aspects of life in Egypt. They put Egypt’s finances in order, constructed a series of dams to modernize its irrigation system, and provided efficient government. But educated Egyptians criticized the British for neglecting such social concerns as education and public health. Egyptian nationalism began to emerge, and some people called for independence.

World War I (1914-1918) had a powerful impact on Egypt’s relationship with the United Kingdom. Egypt was still actually a part of the Ottoman Empire when the war began. After the Ottomans allied with Germany, the British declared Egypt a British protectorate (territory under partial British control). The United Kingdom wanted to protect its interests in Egypt and the Suez Canal. British and Indian troops defended the canal, and British warships prevented enemy ships from using it. Egypt became an important base of Allied operations against Ottoman territory and an important source of labor and supplies. This involvement of Egypt in the war led to outpourings of anti-British sentiment.

Independence.

From 1919 to 1922, Egypt was in political turmoil. Nationalists led by Saad Zaghlul renewed demands for independence. When the British arrested and exiled Zaghlul, discontent against the British turned into revolt. For a few months in 1919, the government broke down. Negotiations produced few results.

Finally in 1922, the United Kingdom granted Egypt its independence. But the British kept many powers, including the right to station troops in Egypt. A new constitution took effect in 1923 that established Egypt as a constitutional monarchy. However, Egypt made little progress toward ridding the country of British forces or improving living standards and economic growth. The monarch struggled with the British and with various political parties for supremacy.

In 1936, Egypt and the United Kingdom agreed to a treaty that reaffirmed Egypt’s independence. This treaty reduced the number of British troops stationed in Egypt and restricted them to the Suez Canal region.

The 1940’s.

During World War II (1939-1945), Italian and German armies invaded Egypt in efforts to capture the Suez Canal. In 1942, the Allies halted the German advance into Egypt in the Battle of El Alamein. Many Egyptians blamed the British for the violence and hunger in Egypt during the war. For more information on Egypt’s involvement in World War II, see World War II (The Western Desert Campaign).

Egypt became a founding member of the United Nations (UN) in 1945. That same year, Egypt and other Arab countries established the Arab League (see Arab League).

After World War II, Egypt’s parliamentary parties tried unsuccessfully to dislodge British forces from Egypt. They also had little success in dealing with such problems as poverty, illiteracy, and disease.

In 1947, the UN voted to divide Palestine into Jewish and Arab states. Israel was established in Palestine in 1948. Egypt and other Arab countries immediately went to war against Israel and were defeated. Egyptians, including army officers, blamed the government for the defeat, and support for such groups as the Muslim Brotherhood increased. The Muslim Brotherhood wanted to establish a strictly Islamic government in Egypt and to reclaim all of Palestine for the Arabs.

Republic.

In July 1952, a discontented army group known as the Free Officers seized power and sent the reigning monarch, King Faruk, into exile (see Faruk I). Gamal Abdel Nasser led the revolt. Nasser believed that Egypt’s government was corrupt and that only a change in government could bring economic progress and complete political independence to Egypt.

The Free Officers organized in a body called the Revolutionary Command Council (RCC). The RCC officially took charge of Egypt in September 1952. The army’s popular commander in chief, Muhammad Naguib, became prime minister. The council banned all political parties that had participated in elections before 1952, including the Muslim Brotherhood. In June 1953, Egypt was declared a republic, with Naguib serving as both president and prime minister.

During the first two years of military rule, Naguib shared power with Nasser, the deputy prime minister. But Naguib and Nasser could not agree on policies. In April 1954, Nasser became prime minister. In October, the United Kingdom agreed to remove all its troops from Egypt by June 18, 1956. In November 1954, Naguib lost the presidency, and Nasser established unchallenged authority over Egypt. See Nasser, Gamal Abdel.

Nasser promoted economic progress in many ways. He increased government spending on education and took over all foreign-run schools. To encourage poor Egyptians to get an education, he provided government jobs for all university graduates. He also wanted to construct a huge new dam on the Nile River to increase the supply of water for irrigation and to provide hydroelectric power (see Aswan High Dam).

Nasser sought financing from other countries for the Aswan High Dam project. The United States and the United Kingdom expressed support for the project, but later, in July 1956, withdrew their offers of financial assistance. In retaliation, the Egyptian government took control of the Suez Canal Company from its British and French owners later that month. Nasser announced that tolls from the canal would provide money for the Aswan High Dam project.

In the meantime, Egypt’s relations with Israel worsened. During the 1950’s, Egypt supported Palestinians who raided Israel from the Gaza Strip, the Egyptian-administered part of Palestine. To retaliate, Israel raided the Gaza Strip. Egypt blocked Israeli ships from the Suez Canal and the Gulf of Aqaba.

In October 1956, Israel, in cooperation with the United Kingdom and France, invaded Egypt. Israel occupied the Sinai Peninsula, and the United Kingdom and France captured Port Said. But the United States and the Soviet Union condemned the invasion and brought pressure to bear on the United Kingdom, France, and Israel. The invading troops withdrew, and the Suez Canal Company eventually was compensated for the loss of its property. A UN peacekeeping force was sent to patrol the Egyptian-Israeli border. Loading the player...

Suez Canal crisis

The United Arab Republic.

Nasser emerged from the Suez incident as a powerful leader of both Egypt and the Arab world. He strongly believed in the importance of unity among the Arab countries. In 1958, a group of Syrian leaders asked Nasser to form a political union between Egypt and Syria. Nasser agreed. The two countries became the United Arab Republic (U.A.R.), and Nasser was elected president of the new nation. Syria eventually grew unhappy with Nasser’s economic policies and his increasing power, and so it withdrew from the U.A.R. in 1961. But Nasser kept United Arab Republic as Egypt’s official name.

In 1962, Egypt intervened in a bitter civil war in Yemen (Sanaa), now part of the country of Yemen. Egyptian soldiers could not end the conflict, but they remained in Yemen (Sanaa) until 1967.

Progress and conflict.

The 1960’s marked a period of economic and social change in Egypt. By 1962, Nasser’s government had taken over almost all of Egypt’s large-scale industries, banks, and businesses. Industry, especially textiles and food processing, expanded. Nasser turned to the Soviet Union for help in building the Aswan High Dam. Construction began in 1960, and the dam began operating in 1968. The dam improved and expanded Egypt’s irrigation system and enabled Egypt to greatly increase its agricultural production.

Nasser took steps to narrow the gap between rich and poor Egyptians through land reform programs and expansion of the educational system. A law passed in 1952 made it illegal to own more than 200 feddans of land. (A feddan equals 1.038 acres, or 0.4201 hectare.) The government distributed any additional land to the fellahin (peasants). Land reform acts in the 1960’s eventually limited land ownership to 50 feddans by any single landowner or to 100 feddans by a family. At the same time, the government built more schools in an attempt to improve educational opportunities. Many poor Egyptians were able to receive an education and eventually rise to professional and bureaucratic positions.

On June 5, 1967, regional tensions erupted again in an Arab-Israeli war. This six-day conflict was brief but decisive. In the war, Israel almost completely destroyed the air forces of Egypt and other Arab countries. The Israeli army then invaded the Sinai Peninsula and positioned itself on the eastern bank of the Suez Canal. When the fighting ended on June 10, Israel also occupied the Gaza Strip, the West Bank of the Jordan River, and the Golan Heights of Syria. The UN arranged a cease-fire.

The war was a territorial and military disaster for the Arab countries. Nasser had overestimated Egypt’s military preparedness. The swift Israeli assaults took the Egyptian forces by surprise.

After the 1967 war, Nasser resigned. But the Egyptian people refused to accept his resignation. Nasser remained president until his sudden death in 1970.

Renewed warfare and peace.

Vice President Anwar el-Sadat won the struggle for power that followed Nasser’s death. He changed Egypt’s official name to the Arab Republic of Egypt in 1971.

Sadat proved to be a shrewd politician. He worked toward two goals: (1) the restoration of lands lost to Israel, and (2) economic growth. To achieve these goals, he believed that the support of the United States was vital. Thus, Sadat broke the ties with the Soviet Union that Nasser had maintained.

In October 1973, along with Syria, Sadat launched a bold and unexpected military assault across the Suez Canal against the Israelis in the Sinai Peninsula. His early success helped win support from other Arab countries. But the Israeli army, resupplied by the United States, eventually drove Egyptian forces back across the Suez Canal. Nevertheless, Sadat drew U.S. attention to the importance of stability in the Middle East and emerged as a powerful world leader. Egypt and Israel agreed to a separation of their forces in the Sinai in 1974. In 1975, they reached an agreement in which Israel removed its troops from a part of the Sinai that it had occupied since 1967. The Suez Canal, which had been closed as a result of the 1967 war, reopened in June 1975.

Sadat sought to regain the entire Sinai Peninsula and to end the state of war readiness that existed between Egypt and Israel. In 1977, he made a historic trip to Israel and addressed the Israeli Knesset (parliament). The following year, Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin met in the United States for discussions with U.S. President Jimmy Carter. The discussions resulted in a major agreement called the Camp David Accords. It was the first such agreement between Israel and an Arab state. The agreement guaranteed the return of the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt, and called for the creation of a peace treaty between Egypt and Israel. The treaty was signed in 1979.

At home, Sadat worked to revitalize the private sector of the economy. His economic policy, called infitah (opening), was designed to allow foreign investment in Egypt and greater private participation in the economy. Sadat hoped to improve relations with the United States and bring about economic growth.

Despite Sadat’s vision, his policies did not meet with great success. Other Arab states rejected his treaty with Israel and criticized Sadat for negotiating independently of them. They removed Egypt from the Arab League in 1979. Many Egyptians felt Sadat had given up too much to Israel to regain the Sinai Peninsula. In addition, prosperity did not follow the signing of the Accords, as many had hoped. Discontent grew, led by radical Islamic groups. A group of extremists assassinated Sadat in October 1981 as he watched a parade.

Egypt under Mubarak.

Vice President Hosni Mubarak succeeded Sadat as president. He reaffirmed Sadat’s peace treaty with Israel, sustained ties with the United States, and encouraged the private sector of the economy. But Mubarak was much less outspoken on many controversial issues and worked to repair Egypt’s ties with other Arab countries. Egypt was readmitted to the Arab League in 1989.

Egypt’s strategic importance enabled it to gain economic and military aid from the United States and the Soviet Union. But these alliances did not benefit the people greatly. Egypt’s problems remained much the same as throughout the 1900’s. The population had become too large for Egypt’s resources and continued to grow rapidly.

In 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait. Egypt took a leading role in Arab opposition to the invasion. In early 1991, war broke out between Iraq and a coalition that was formed by the United States, Egypt, and other nations. Egyptian troops participated in the efforts to liberate Kuwait (see Persian Gulf War of 1991).

In October 1992, an earthquake struck Cairo and neighboring suburbs. The disaster caused more than 560 deaths and about $1 billion in property damages.

Violence by radical Islamist organizations, particularly the Islamic Group, increased in the early 1990’s. These groups attacked Egyptian Christians and foreigners, especially foreign tourists. In a crackdown on the violence, Egyptian authorities raided extremist strongholds. They made mass arrests and imprisoned thousands of suspects. A number were executed. The Egyptian government also used the state-controlled media to discredit armed Islamist groups. As a result, extremist violence became less of a threat by the end of the 1990’s. However, restrictive emergency regulations remained in place.

In 1997, President Mubarak launched a massive development project to irrigate desert land and turn it into farmland. Under this project, water was to be pumped from Lake Nasser through a canal to a region of the Western Desert. The area under development was to be called the New Valley. The government expected the New Valley to provide homes and farms for Egypt’s fast-growing population.

Meanwhile, Egypt’s government sold some of its companies to private owners. The aim of this privatization was to attract domestic and foreign investment, help the country’s economy, and create jobs.

In the early 2000’s, Egypt saw a resumption of violence against tourist areas. Bombings in October 2004 and July 2005 killed dozens of people at resorts on the Sinai Peninsula bordering the Red Sea. Egyptian officials blamed Islamist extremists for the attacks.

Egypt held its first multicandidate presidential election in September 2005, and President Mubarak was reelected to a fifth term. In December, Egyptians elected a new parliament. Mubarak’s party retained a majority, but the Muslim Brotherhood party gained 20 percent of the seats. The Muslim Brotherhood party was banned at the time, but candidates ran as independents.

In March 2007, voters approved amendments to the constitution in a referendum. The amendments included restrictive antiterrorism measures, increased presidential powers, and a ban on religion-based political parties and political activities. However, the Muslim Brotherhood boycotted the referendum, and opposition members claimed that it was fraudulent.

Recent developments.

Amid steady demonstrations against military rule, Egyptians voted in parliamentary elections in late 2011. Islamist parties won the vast majority of seats. In June 2012, voters elected Mohamed Morsi of the Freedom and Justice Party (FJP) as Egypt’s new president. The FJP is the political arm of the Muslim Brotherhood.

In November, Morsi sparked large protests by attempting to give himself what some Egyptians considered dictatorial powers. In December, Egyptian voters approved a new constitution. In July 2013, however, after mass protests and antigovernment demonstrations, the Egyptian army suspended the constitution and forced President Morsi from office. More than 1,000 people died as protests led to violence between Morsi supporters and security forces. Adly Mansour, head of the Supreme Constitutional Court, was named interim president.

In September 2013, the Egyptian government again banned the Muslim Brotherhood. Blaming the group for bombings and other acts of violence, the government declared the Muslim Brotherhood a terrorist organization. In January 2014, Egyptian voters again approved a new constitution. In June, former army commander in chief Abdel Fattah el-Sisi became Egypt’s new president. In October, the Egyptian government declared a state of emergency in parts of the Sinai Peninsula after an increase in attacks by extremists linked to the radical militant group Islamic State, also known as the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL).

In February 2015, Islamic State militants massacred 21 Egyptian Christians in neighboring Libya, a nation destabilized by warring militias. In response, Egyptian warplanes bombed suspected Islamic State camps and training sites in Libya. Since then, sporadic terrorist violence has continued in Egypt, particularly in the Sinai Peninsula.

In 2016, construction began on a new administrative capital east of Cairo. The new city, designed to relieve overcrowding in Cairo, is to include government ministries, housing for workers, and green space.

In 2018, President Sisi was reelected with little opposition. In a referendum held in 2019, Egyptian voters approved a number of changes to the Constitution that extended the president’s term and affected the government’s structure. But fewer than half of Egypt’s voters participated in the referendum. In late 2019, protests broke out against Sisi. Demonstrators protested against a prolonged period of economic austerity, alleged government corruption, and the Sisi government’s intolerance of any form of dissent. The government responded with a harsh crackdown on the protesters in which thousands of people were arrested.

In 2020, voters elected a Senate. The new legislative body was Egypt’s first parliamentary upper house since 2014, when the new constitution eliminated the Shura Council. The pro-government Mostaqbal Watan (Nation’s Future) Party won a majority of seats in the Senate. The party also won a majority of seats in an election for the lower house, the House of Representatives. In 2023, President Sisi was elected to a third term, again with little opposition.

In 2020, Egypt faced a public health crisis as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (worldwide epidemic). COVID-19 is a sometimes-fatal respiratory disease caused by a coronavirus. Egypt reported its first case of the disease in early 2020. To curb the spread of COVID-19, the government limited travel, as well as business, educational, and social activities. In mid-2020, the government allowed some businesses to reopen. Egypt began administering COVID-19 vaccines in early 2021. By early 2023, more than 500,000 people in Egypt had been infected with the virus, and about 25,000 of them had died from the disease.