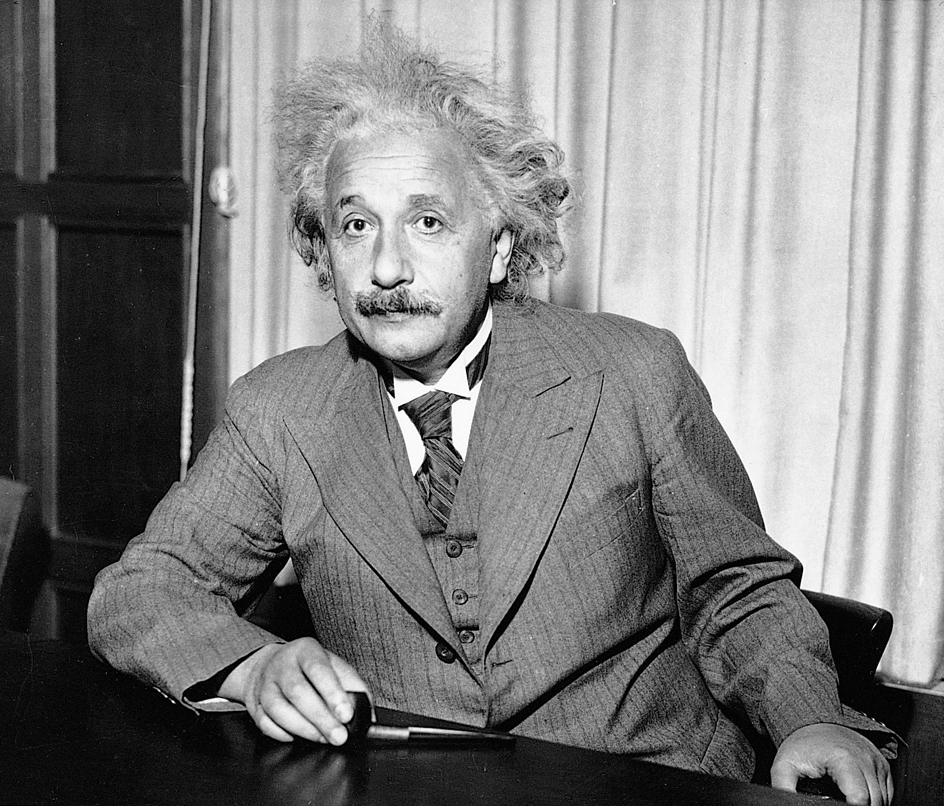

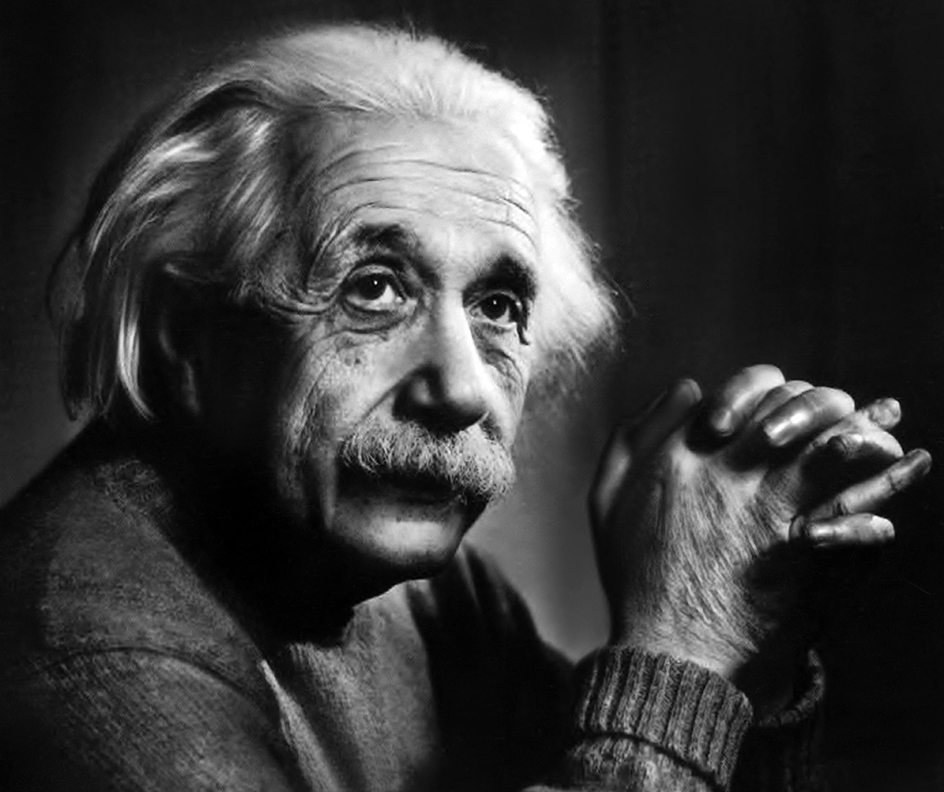

Einstein, Albert (1879-1955), was the most important physicist of the 1900’s and one of the greatest and most famous scientists of all time. He was a theoretical physicist, a scientist who creates and develops theories of matter and energy. Einstein’s greatness arose from the fact that his theories solved fundamental problems and presented new ideas. Much of his fame came from the fact that several of those ideas were strange and hard to understand—but proved true.

Some of Einstein’s most famous ideas make up parts of his special theory of relativity and his general theory of relativity. For example, the special theory describes an entity known as space-time. This entity is a combination of the dimension of time and the three dimensions of space—length, width, and height. Thus, space-time is four-dimensional. In the general theory, matter and energy distort (change the shape of) space-time; the distortion is experienced as gravity.

Einstein also became known for his support of political and social causes. Those included pacifism, a general opposition to warfare; Zionism, a movement to establish a Jewish homeland in Palestine; and socialism, a political system in which the means of production would be owned by society and production would be planned to match the needs of the community.

Early years

Einstein was born on March 14, 1879, in Ulm, in southern Germany, the son of Hermann Einstein and Pauline Koch Einstein. The next year, Hermann moved the family about 70 miles (110 kilometers) to Munich.

Albert Einstein’s younger sister, Maria—whom he called Maja (pronounced MAH yah)—recalled that Einstein was slow to learn to speak. But even as a young child, he displayed the powers of concentration for which he became famous.

Einstein recalled seeing the seemingly miraculous behavior of a magnetic compass when he was about 5 years old. The fact that invisible forces acted on the compass needle made a deep impression on the boy.

A booklet on Euclidean geometry made a comparable impression on Einstein when he was around 12 years old. Euclidean geometry is based on a small number of simple, self-evident (obviously true) statements about geometric figures. Mathematicians use those statements to deduce (develop by reasoning) other statements, many of which are complex and far from self-evident. Einstein was impressed that geometric statements that are not self-evident could be proved clearly and with certainty.

Education.

Einstein began to take violin lessons when he was 6 years old. He eventually became an accomplished violinist, and he played the instrument throughout his life.

At the age of 9, Einstein entered the Luitpold Gymnasium, a distinguished secondary school in Munich. He enjoyed some of his classes and performed well, but he disliked the strict discipline. As a result, he dropped out at the age of 15 to follow his parents to Pavia, Italy, near Milan.

Einstein finished high school in 1896, in Aarau, Switzerland. He then entered a school in Zurich, Switzerland, that ranked as one of Europe’s finest institutions of higher learning in science. The school is known as the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich or the ETH Zurich, from the initials for Federal Institute of Technology in German. While at the ETH, Einstein met and fell in love with Mileva Maric. Mileva was a physics student from Novi Sad, in what is now Serbia.

Einstein often skipped class, relying on the notes of others. He spent his free time in the library reading the latest books and physics journals. Einstein’s behavior annoyed Heinrich F. Weber, the professor who supervised his course work. Although professors customarily helped their students obtain university positions, when Einstein neared graduation, Weber did not help him get a university post. Instead, a friend helped him find a job as a clerk in the Swiss Federal Patent Office in Bern. He became a Swiss citizen in 1901.

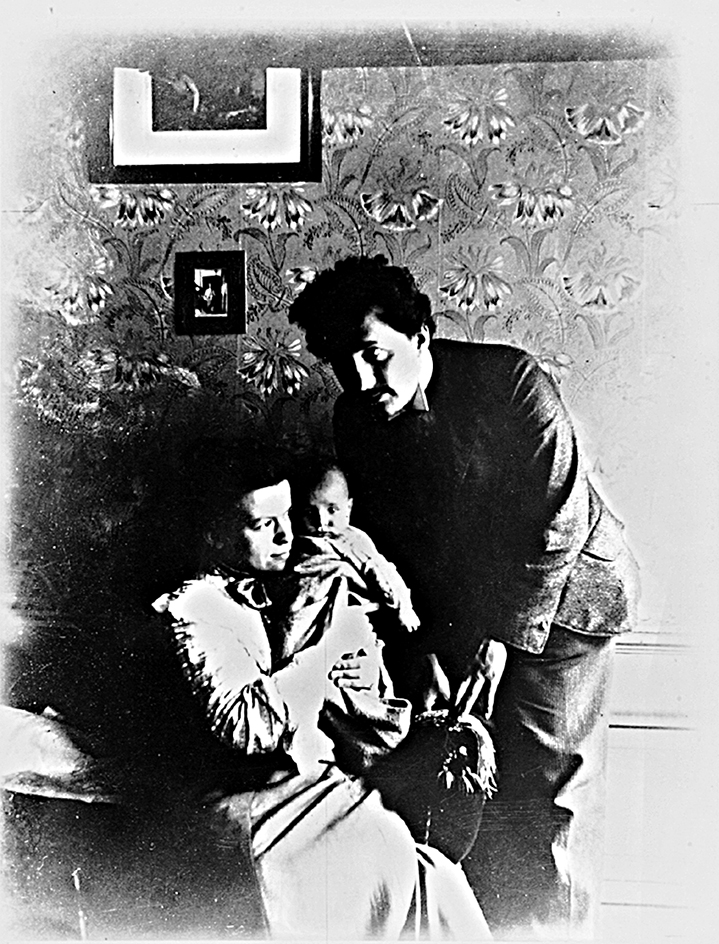

First marriage.

Meanwhile, Mileva had become pregnant. Albert and Mileva’s child, a daughter they named Lieserl, was born in January 1902 at the home of Mileva’s parents. In January 1903, Albert and Mileva married. They had two more children, Hans Albert in 1904 and Eduard in 1910. However, Lieserl never joined them in Bern, and her fate remains a mystery.

Famous theories.

Einstein worked at the patent office from 1902 to 1909. Those years were among Einstein’s most productive. The job of reviewing patent applications left him with much time for physics. In 1905, he obtained a Ph.D. degree in physics by submitting a dissertation (a long, formal paper) to the University of Zurich. He had already completed all the necessary classwork at the ETH.

The year 1905 is known as Einstein’s annus mirabilis—Latin for year of marvels. In that year, the German scientific periodical the Annalen der Physik (Annals of Physics) published three of his papers that were among the most revolutionary in the history of science.

The photoelectric effect.

The first paper, published in March 1905, deals with the photoelectric effect. By means of that effect, a beam of light can cause metal atoms to release subatomic particles called electrons. In a photoelectric device, these freed electrons flow as electric current, so the device produces a current when light shines on it.

Einstein explained that the photoelectric effect occurs because light comes in “chunks” of energy called quanta. The singular of quanta is quantum. A quantum of light is now known as a photon. An atom can absorb a photon. If the photon has enough energy, an electron will leave its atom. Einstein received the 1921 Nobel Prize in physics for his paper on the photoelectric effect.

The principle that light comes in quanta is a part of an area of physics known as quantum mechanics. Quantum mechanics is one of the “foundation blocks” of modern physics; Einstein’s relativity theories are two others.

Brownian motion.

In the second paper, published in May 1905, Einstein explained Brownian motion, an irregular movement of microscopic particles suspended in a liquid or a gas. Such motion was named for the Scottish botanist Robert Brown, who first observed it in 1827. Einstein’s analysis stimulated research on Brownian motion that produced the first experimental proof that atoms exist.

The special theory of relativity.

The third paper, published in June, presented the special theory of relativity. In that paper, titled “On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies,” Einstein made a remarkable statement about light. He said that constant motion does not affect the velocity (speed in a particular direction) of light.

Imagine, for example, that you are on a railroad car traveling on a straight track at a constant speed of one-third the speed of light. You flash a light from the back of the car to the front of the car. You precisely measure the speed of the light. You find that the speed is 186,282 miles (299,792 kilometers) per second—represented by the letter c in scientific equations. A friend standing on the ground also measures the speed of the light.

You might expect your friend’s result to be c + 1/3 c. That would be a “common-sense” result consistent with ordinary experience with the velocities of material objects. For example, a ball thrown forward inside a railroad car would have a velocity—as measured by an observer on the ground—equal to the velocity of the car plus the velocity of the ball as measured in the car. But, strangely, in the case of the light beam, your friend’s answer turns out to be the same as yours: c.

The strange fact that the velocity of light is constant has even stranger results. For example, a clock can appear to one observer to be running at a given rate, yet seem to another observer to run at a different rate. Two observers can measure the length of the same rod correctly but obtain different results.

Einstein also said that c is a universal “speed limit.” No physical process can spread through space at a velocity higher than c. No material body can reach a velocity of c.

Interchangeability of mass and energy.

In a fourth paper, published in September 1905, Einstein discussed a result of the special theory of relativity—that energy and mass are interchangeable.

Mass is a measure of an object’s inertia, its resistance to a change in its motion. An object at rest tends to remain at rest due to inertia. A moving object tends to maintain its velocity. In addition, an object’s weight is proportional to its mass; more massive objects weigh more.

The paper introduced Einstein’s famous equation E = mc-squared (E = mc 2). The equation says that a body’s energy, E, equals the body’s mass, m, times the speed of light, c, squared (multiplied by itself). The speed of light is so high that the conversion of a tiny quantity of mass releases a tremendous amount of energy.

The conversion of mass creates energy in the sun and other stars. It also produces the heat energy that is converted to electric energy in nuclear power plants. In addition, mass-to-energy conversion is responsible for the tremendous destructive force of nuclear weapons.

Middle years

Academic appointments.

By 1909, Einstein was famous within the physics community. That year, he accepted his first regular academic appointment, as an associate professor of theoretical physics at the University of Zurich. In 1911, he became a professor at the German University in Prague, Austria-Hungary (now Charles University in the Czech Republic). In 1912, he returned to the ETH as a professor.

Einstein moved to Berlin in 1914 to become a member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences, a professor at the University of Berlin, and the director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics, a research center then in the planning stage. He headed the institute until 1933. After World War II (1939-1945), the institute was renamed the Max Planck Institute (MPI) for Physics. Several other MPI’s for various branches of physics and for other fields of study were later founded.

Second marriage.

Mileva went with Albert to Berlin in March 1914 but returned to Zurich in June. Their marriage had become unhappy; and, in 1919, Albert divorced Mileva and married his cousin Elsa Einstein Lowenthal. Einstein’s sons stayed in Zurich with Mileva, and Albert adopted Elsa’s daughters, Ilse and Margot.

The general theory of relativity.

In 1916, the Annalen der Physik published Einstein’s paper on the general theory of relativity. This paper soon made Einstein world-famous. He suggested that astronomers could confirm the theory by observing the sun’s gravitation bending light rays. During a solar eclipse in 1919, the British astronomer Arthur S. Eddington detected the bending aside of starlight by the sun’s gravitational field. His observation supported Einstein’s theory.

Loading the player...Albert Einstein talks about the hydrogen bomb

In his theory, Einstein also showed that gravity affects time—the presence of a strong gravitational field makes clocks run more slowly than normal. In addition, equations in the general theory are the basis of descriptions of black holes. A black hole is a region of space whose gravitational force is so strong that nothing can escape from it. A black hole is invisible because it traps even light.

Attacks on Einstein.

Einstein’s world fame came at a price. Einstein was of Jewish descent, and anti-Semitism (prejudice against Jews) was increasing in Germany. The physicist and his theories became targets of anti-Semitic verbal attacks. Following the 1922 murder of German foreign minister Walther Rathenau, who was Jewish, Einstein temporarily left Germany. He visited Palestine and a number of other Asian countries, Spain, and South America.

World travel.

Threats of danger did not prevent Einstein from using his fame to promote causes dear to his heart. He took his first trip to the United States in 1921. The main purpose of the trip was not to lecture on physics but to raise money for a planned Hebrew University of Jerusalem. In July 1923, he traveled to Sweden to accept the Nobel Prize in physics that had been awarded to him in 1921.

Further scientific work.

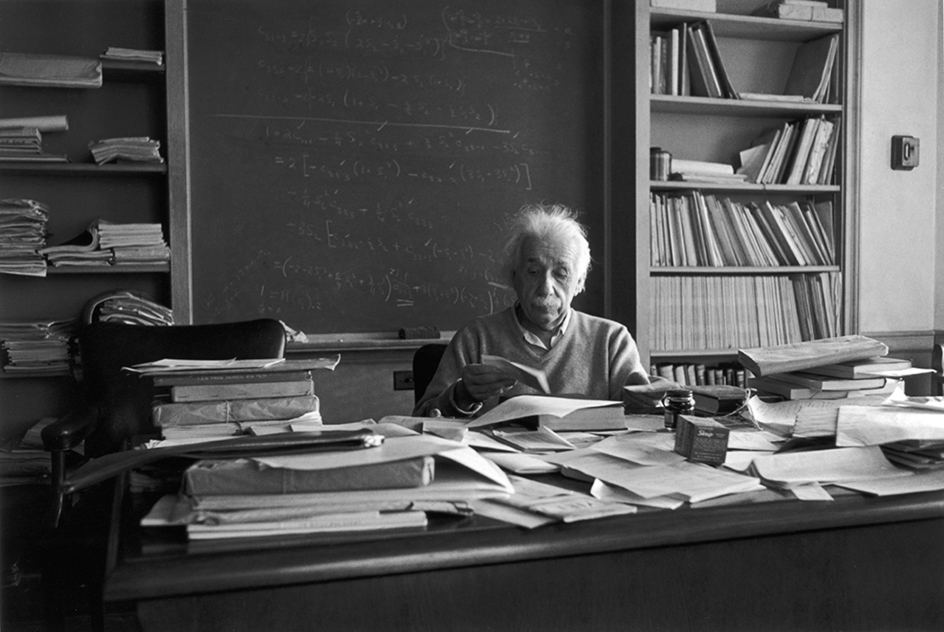

After creating the general theory of relativity, Einstein worked on a unified field theory that was to include all electric, magnetic, and gravitational phenomena. Such a theory would provide a single description of the physical universe, rather than separate descriptions for gravitation and other phenomena. Einstein worked on the theory for the rest of his life but never finished it; to this day, no one has developed a fully successful unified field theory.

Through the mid-1920’s, Einstein was a major contributor to the development of quantum mechanics. By the late 1920’s, however, he had begun to doubt the theory.

One reason for Einstein’s doubt was that parts of quantum mechanics did not seem to be deterministic. Determinism states that strict laws involving causes and effects govern all events. As an example of apparent nondeterminism in quantum mechanics, consider an atom that absorbs a photon, thereby becoming more energetic. At a later moment, the atom reduces its energy level by releasing a photon. But a physicist cannot use quantum mechanics to predict the moment of release.

In 1926, Einstein wrote a famous letter to the German physicist Max Born expressing his doubts about quantum mechanics. Einstein wrote, “The theory produces a good deal but hardly brings us closer to the secret of the Old One [by which Einstein meant God]. I am at all events convinced that He does not play dice.”

In 1935, Einstein and the German physicists Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen published an article, which became known as the “EPR paper,” arguing that quantum mechanics is not a complete theory. The EPR paper and a reply from the Danish physicist Niels Bohr became the basis for a scientific debate that continues to this day.

Later years

Einstein in the United States.

In December 1930, Einstein traveled to the United States. His trip was the first of what were meant to be annual visits to lecture at the California Institute of Technology. But in January 1933, during Einstein’s third trip, the Nazi Party seized power in Germany. The Nazis had an official policy of anti-Semitism, and so Einstein never set foot in Germany again. He returned to Europe in March 1933, staying in Belgium under the protection of that country’s royal family. He then went to England.

In September 1933, Einstein sailed to the United States to work at the Institute for Advanced Study, an independent community of scholars and scientists doing advanced research and study. The institute had recently been established in Princeton, New Jersey, and now consists of schools of Historical Studies, Mathematics, Natural Sciences, and Social Science. Princeton would be Einstein’s home for the rest of his life. Einstein became a United States citizen in October 1940.

Letter to President Roosevelt.

Einstein undertook one of his most important acts in the summer of 1939, shortly before the outbreak of World War II. At the urging, and with the help, of the Hungarian refugee physicist Leo Szilard, Einstein wrote a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The letter warned that German scientists might be working on an atomic bomb. The letter led to the establishment of the Manhattan Project, which produced the first atomic bomb in 1945.

Continuing fame.

After World War II, Einstein worked tirelessly for international controls on atomic energy. He had a wide circle of professional acquaintances and friends, and he was still a world figure. In 1952, he was offered the presidency of Israel—the modern state of Israel had existed only since 1948—but he declined.

Final days.

By the early 1950’s, Einstein’s immediate family had dwindled. His son Eduard had been confined to a mental institution in Zurich for years, suffering from schizophrenia. Einstein’s first and second wives, his stepdaughter Ilse, and his sister Maja, to whom he had been especially close, had died. Einstein’s son Hans Albert was a professor of civil engineering at the University of California in Berkeley. Of the people who were emotionally close to Albert Einstein, only his stepdaughter Margot and Helen Dukas, his secretary since 1928, remained with him in Princeton.

Einstein signed his last letter one week before his death. In the letter, to the British philosopher and mathematician Bertrand Russell, Einstein agreed to include his name on a document urging all nations to give up nuclear weapons. Einstein died in Princeton on April 18, 1955.