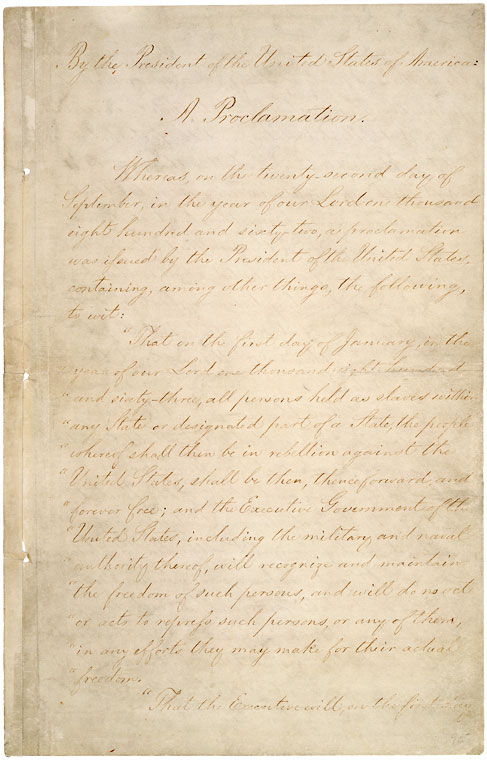

Emancipation Proclamation is a historic document that led to the end of slavery in the United States. President Abraham Lincoln issued the proclamation on Jan. 1, 1863, during the American Civil War (1861-1865). The proclamation declared freedom for enslaved persons in all areas of the Confederacy that were still in rebellion against the Union. It also allowed Black Americans to serve in the Union Army and Navy, thus aiding the North’s victory in the war. Today, the original document is kept in the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C.

Events leading to the proclamation

Early views on emancipation.

The 11 states of the Confederacy seceded (withdrew) from the Union in 1860 and 1861. They seceded primarily because they feared the newly elected Lincoln would restrict their right to do as they chose regarding Black slavery. The North entered the Civil War only to reunite the nation, not to end slavery.

During the first year and a half of the war, abolitionists and some Union military leaders urged Lincoln to take action to free enslaved people. They argued that such a policy would help the North because enslaved people were contributing greatly to the Confederate war effort. By doing most of the South’s farming and factory work, enslaved Black people made white men available to fight for the Confederate Army.

Lincoln agreed with the abolitionists’ view of slavery. He once declared that “if slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong.” When he ran for president in 1860, he promised to prevent the spread of slavery to the West. But early in the war, Lincoln believed that if he freed the enslaved people, he would divide the North. He feared that four border states that permitted slavery—Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri—would secede if he adopted such a policy. In addition, the Constitution of the United States gave him no power to end slavery in places that remained loyal to the Union.

Loading the player...Abraham Lincoln

Lincoln’s change of policy.

In July 1862, with the war going badly for the North, Congress passed a law freeing all enslaved people from Confederate states who crossed behind Union lines. But the law had limited impact. It left local federal courts to decide disputes about whether to grant an enslaved person freedom, and in the Confederacy, such courts no longer existed. At about this same time, Lincoln decided to change his stand on slavery. However, he waited for a Union military victory so that his decision would not appear desperate.

On Sept. 22, 1862, five days after Union forces won the Battle of Antietam, Lincoln issued a preliminary proclamation. It stated that if the rebelling states did not return to the Union by Jan. 1, 1863, he would declare enslaved people in those states to be “forever free.” The South ignored Lincoln’s warning, and so he issued the Emancipation Proclamation on Jan. 1, 1863. Lincoln took this action as commander in chief of the Army and Navy of the United States. He called it “a fit and necessary war measure.” His decision provoked outrage in the South, as well as much opposition in the North.

Effects of the proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation did not immediately free a single enslaved person, because it affected only areas still under Confederate control. It excluded enslaved people in the border states and in Southern areas under Union control, such as Tennessee and parts of Louisiana and Virginia. But from 1863 to the end of the war in 1865, the proclamation meant the advancing Union armies brought freedom to enslaved people in areas where the Union took military control. It also helped to encourage the border state of Maryland to end slavery and led to the 13th Amendment to the Constitution. This amendment, which became law on Dec. 18, 1865, ended slavery in all parts of the United States.

As Lincoln had hoped, the Emancipation Proclamation strengthened the North’s war effort and weakened the South’s. By the end of the war, more than 500,000 enslaved people had fled to freedom behind Northern lines. Many of them joined the Union Army or Navy, or worked for the armed forces as laborers. By allowing Black people to serve in the Army and Navy, the Emancipation Proclamation helped solve the North’s problem of declining enlistments. About 200,000 Black soldiers and sailors, many of them formerly enslaved, served in the armed forces. They helped the North win the war.

The Emancipation Proclamation also hurt the South by discouraging the United Kingdom and France from entering the war. Both of those nations depended on the South to supply them with cotton, and the Confederacy hoped that they would fight on its side. But the proclamation made the war a fight against slavery. The United Kingdom and France had already abolished slavery, and so they gave their support to the Union.

From a moral point of view, the Emancipation Proclamation transformed the United States and at last began to correct a great flaw in the Constitution. Lincoln well understood the importance of what many scholars have called his greatest presidential act. The day he signed it, Lincoln said, “If my name ever goes into history it will be for this act, and my whole soul is in it.”

See also Adams, John Quincy (The Gag Rules); Civil War, American; Constitution of the United States (Amendment 13).